Nutritional Showdown: Assessing the Quality and Health Impacts of Local Landraces vs. Improved Food Varieties

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and scientists on the nutritional profiles of local/traditional food varieties compared to improved/modern cultivars.

Nutritional Showdown: Assessing the Quality and Health Impacts of Local Landraces vs. Improved Food Varieties

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and scientists on the nutritional profiles of local/traditional food varieties compared to improved/modern cultivars. It explores the foundational definitions and historical contexts of both categories, examines advanced methodological frameworks for nutritional quality assessment, investigates challenges in breeding and analysis, and presents comparative data on health outcomes. By synthesizing evidence from agricultural, nutritional, and biomedical literature, this review aims to inform strategic decisions in crop development, nutritional epidemiology, and the creation of functional foods with enhanced health benefits.

Defining the Contenders: Unpacking the Agronomic and Nutritional Profiles of Local and Improved Varieties

Crop varieties form the foundational unit of agricultural production and nutritional security. In the context of ongoing research comparing the nutritional quality of local versus improved varieties, a clear understanding of the distinct categories of plant genetic resources is essential. This guide provides a structured framework for researchers and scientists, defining key varietal terms, summarizing comparative nutritional data, detailing standard experimental protocols, and visualizing core research pathways. The precise classification of plant material is crucial, as the genetic diversity harbored in traditional varieties serves as a key resource for breeding more nutritious and resilient crops [1]. This document objectively compares these categories to inform research and development decisions.

Defining the Varietal Spectrum

The continuum of crop varieties ranges from wild relatives to modern commercial hybrids, each with distinct origins, characteristics, and roles in agriculture and nutrition. The table below provides a comparative summary of the four key categories relevant to this guide.

Table 1: Conceptual Framework of Crop Variety Categories

| Category | Definition & Origin | Key Characteristics | Primary Role in Nutrition & Breeding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local Varieties | A broad term for cultivars developed and adapted to specific local growing conditions and cultural practices. | Locally adapted, genetically variable, often maintained by informal seed systems [2]. | Maintain agrobiodiversity; direct source of nutrition for local communities; potential source of adaptive traits. |

| Landraces | Traditional, locally adapted cultivars developed through natural and human selection over generations, often without formal breeding [1] [3]. | High genetic diversity, heterogeneity, adaptation to local environments, and historical origin [1] [3]. | Valuable gene reservoirs for enhancing nutritional traits (e.g., minerals, phenolics) and stress resilience in modern cultivars [1] [4] [3]. |

| Improved Varieties | Cultivars developed through formal plant breeding programs to enhance specific traits such as yield, disease resistance, or uniformity [1]. | High yield, homogeneity, distinct and stable traits, and often wide adaptation [1]. | Provide caloric sufficiency; modern focus on yield can sometimes lead to nutritional dilution [5]. |

| Biofortified Varieties | A subset of improved varieties specifically bred using conventional or transgenic methods to increase the density and bioavailability of essential micronutrients [6] [7] [8]. | Nutrient-dense edible parts; designed to reduce micronutrient deficiencies; no yield penalty [6] [4] [7]. | Targeted intervention to combat "hidden hunger" (micronutrient deficiencies) by increasing nutrient intake from staple foods [6] [7] [8]. |

Comparative Nutritional Analysis

Quantitative data reveals significant differences in the nutritional profiles of landraces, improved, and biofortified varieties. The following tables summarize experimental findings from key crops.

Table 2: Comparative Mineral and Protein Content in Sorghum Genotypes Developed from Landraces

| Sorghum Genotype | Crude Protein (%) | In Vitro Protein Digestibility (IVPD) (%) | Total Iron (mg/100g) | Total Zinc (mg/100g) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PYPS 2 | 13.21 | 18.68 | Data not specified | Data not specified | [4] |

| PYPS 13 | 12.80 | 19.56 | Data not specified | Data not specified | [4] |

| Range across 19 Genotypes from Landraces | Not specified | Not specified | 14.21 – 28.41 | 4.81 – 8.16 | [4] |

Table 3: Nutritional Changes Associated with the Shift to Modern Varieties

| Nutrient | Reported Decline in Modern Crops | Time Period | Crops Studied | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium | Up to 46% | Over 50-70 years | Various fruits & vegetables | [5] |

| Iron | Up to 50% | Since 1940 | Various fruits & vegetables | [5] |

| Copper | Up to 81% | Since 1936 | Twenty vegetables | [5] |

| Vitamin A | 21.4% | 1975-1997 | Various fruits & vegetables | [5] |

| Vitamin C | 29.9% | 1975-1997 | Various fruits & vegetables | [5] |

Table 4: Global Impact of Biofortified Varieties (as of 2024)

| Crop | Biofortified Nutrient | Key Region of Impact | Estimated Reach | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beans | Iron | Africa | Widespread adoption in countries like Rwanda | [7] |

| Cassava, Maize, Sweet Potato | Vitamin A | Africa | Millions of farm households in Nigeria and beyond | [7] |

| Pearl Millet | Iron | Asia | Primary impact in target countries | [7] |

| Rice, Wheat | Zinc | Asia | Fast adoption in countries like Pakistan | [7] |

| Overall | Iron, Zinc, Vitamin A | 41+ countries | ~330 million people consuming biofortified foods | [7] |

Essential Research Protocols

Protocol for Nutritional Profiling of Grains

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to evaluate the nutritional improvement of sorghum genotypes developed from landraces [4].

- Sample Preparation: Collect whole grains from field trials. Clean, mill, and sieve through a 0.4 mm sieve. Store the fine flour at 4°C until analysis.

- Crude Protein Analysis: Determine crude protein content using the Kjeldahl method. Digest the sample in concentrated sulfuric acid with a catalyst to convert organic nitrogen to ammonium sulfate. Distill the digest with sodium hydroxide, trap the released ammonia in boric acid, and titrate with standard acid to calculate nitrogen content. Multiply by a conversion factor (typically 6.25 for cereals) to obtain crude protein [4].

- In Vitro Protein Digestibility (IVPD): Calculate IVPD using the formula:

IVPD (%) = (digestible protein / total protein) * 100[4]. Digestible protein is determined via enzymatic assays simulating human digestion. - Mineral Analysis (Iron and Zinc):

- Total Mineral Extraction: Ash the sample in a muffle furnace at 550°C. Dissolve the ash in 5N HCl.

- Bioavailable Mineral Extraction: Shake 1g of sample in 10 mL of 0.03M HCl for 3 hours at 37°C to simulate gastric digestion. Oven-dry the clear extract and then acid-digest it.

- Quantification: Determine Iron (Fe) and Zinc (Zn) concentrations in both extracts using an Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (AAS) [4].

- Phytochemical Analysis:

- Total Phenolics: Extract with methanol and quantify using the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, expressing results as mg Gallic Acid Equivalents (GAE) per g of sample.

- Antioxidant Activity: Assess using the DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging assay, with results expressed as percentage inhibition [4].

- Tannins: Quantify using the vanillin-HCl method or other standardized assays.

Protocol for Genomic Analysis of Landraces

This protocol outlines the use of modern genomic tools to identify valuable traits in landraces for breeding programs [3].

- Population Development: Create mapping populations such as Recombinant Inbred Lines (RILs) or Multi-parent Advanced Generation Inter-Cross (MAGIC) populations by crossing landraces (donors of specific traits) with elite improved varieties.

- Genotyping: Extract DNA from plant tissue. Genotype the population using high-density molecular markers, preferably Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs), using platforms like SNP arrays or whole-genome sequencing.

- Phenotyping: Grow the population in replicated field trials and meticulously record data on target traits (e.g., nutrient content, stress tolerance, yield components).

- Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) Mapping / Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS):

- QTL Mapping: For biparental populations (e.g., RILs), use statistical software to identify genomic regions (QTLs) where marker alleles correlate with the variation of the phenotyped trait.

- GWAS: For diverse panels of landraces and varieties, use mixed linear models to test for associations between each SNP marker and the trait of interest across the entire genome, accounting for population structure.

- Candidate Gene Identification: Use the reference genome of the crop to identify putative genes within the significant QTLs or associated genomic regions. Validate gene function through techniques like gene expression analysis (RNA-seq) or gene editing (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9) [3].

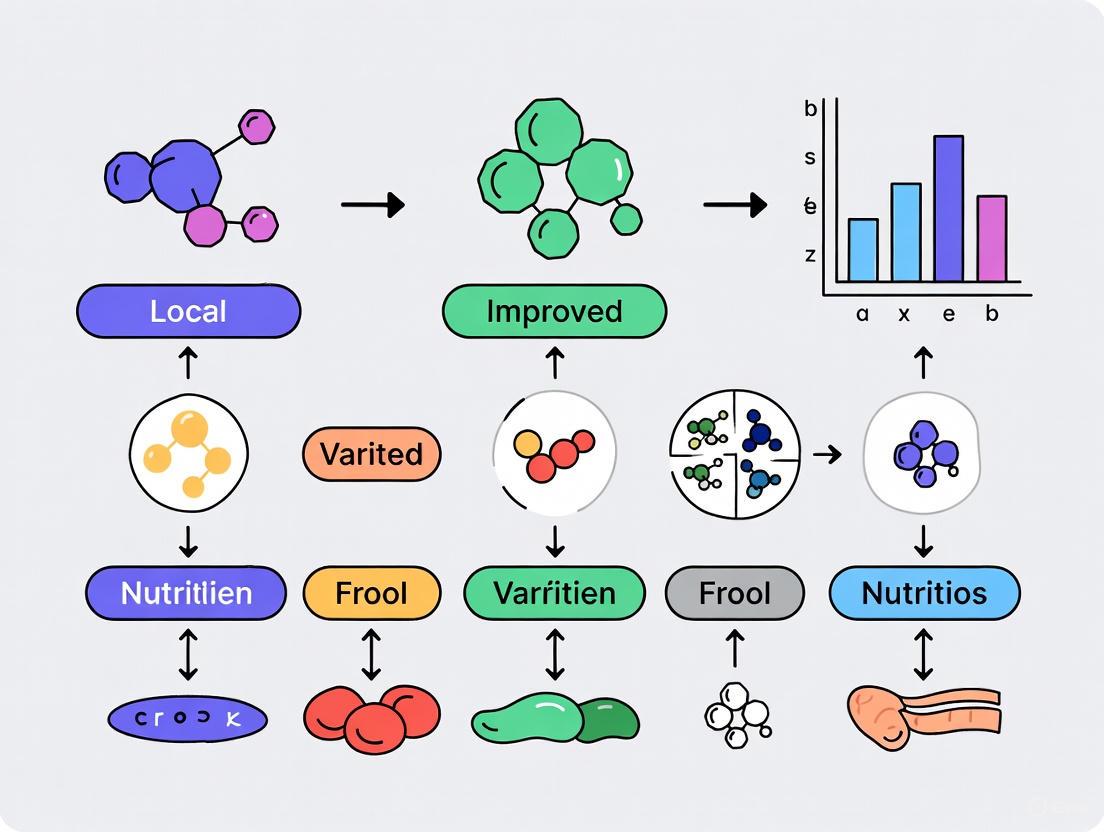

Visualizing Research Pathways

From Landrace to Improved Variety

Experimental Nutrition Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Nutritional and Genomic Studies

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (AAS) | Quantifies the concentration of specific metallic elements (e.g., Fe, Zn) in a sample. | Measuring total and bioavailable iron and zinc in grain flour [4]. |

| Kjeldahl Digestion Apparatus | Digests organic samples to convert nitrogen into a quantifiable form for protein calculation. | Determining the crude protein content in sorghum grains [4]. |

| Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent | A chemical reagent used in colorimetric assays to measure the total phenolic content in plant extracts. | Quantifying antioxidant-related compounds in pigmented rice or sorghum landraces [9] [4]. |

| DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) | A stable free radical used to evaluate the antioxidant activity of plant compounds via a scavenging assay. | Assessing the radical scavenging capacity of extracts from traditional varieties [4]. |

| SNP (Single Nucleotide Polymorphism) Arrays | High-throughput genotyping platforms that assay hundreds of thousands of genetic markers across the genome. | Conducting GWAS on collections of landraces to find genes associated with nutritional traits [3]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | A gene-editing tool that allows for precise modification of DNA sequences within an organism. | Validating the function of candidate genes identified in landraces for nutrient accumulation [3]. |

For decades, the primary objective of agricultural breeding programs was singular: yield maximization. Driven by the need to ensure global food security, particularly during the mid-20th century, breeders successfully developed high-yielding varieties that averted large-scale famine. However, this yield-focused approach often occurred at the expense of nutritional quality, leading to the phenomenon of "hidden hunger" – micronutrient deficiencies that affect over two billion people globally despite adequate caloric intake [10]. This article examines the historical transition from yield-centric breeding to contemporary strategies that prioritize nutritional enhancement, providing a comparative analysis of the nutritional profiles of local versus improved crop varieties within this evolving context.

The foundation of this shift lies in the growing recognition that our major food crops are often poor sources of essential micronutrients required for normal human growth, and the soils in which they grow are becoming increasingly depleted of minerals [10]. Furthermore, emerging challenges such as climate change and rising atmospheric CO₂ concentrations are predicted to reduce the concentrations of essential nutrients like zinc, iron, and protein in staple cereals, potentially placing hundreds of millions at risk of nutrient deficiencies [10]. In response, breeding strategies have evolved to embrace biofortification – the process of increasing the density of vitamins and minerals in crops through genetic improvement – as a sustainable approach to addressing malnutrition [10].

Historical Context: The Yield-Nutrition Tradeoff

Historical evidence suggests a potential trade-off between yield maximization and nutritional quality in crop development. A comparative study of USDA nutrient composition data for 43 garden crops between 1950 and 1999 revealed apparent, statistically reliable declines for six nutrients: protein (6%), calcium (16%), phosphorus (9%), iron (15%), riboflavin (38%), and ascorbic acid [11]. The study hypothesized that these declines might be explained by changes in cultivated varieties during this period, where breeding efforts prioritized yield and agronomic characteristics over nutritional content [11].

This trade-off presents a fundamental challenge: while agricultural production successfully shifted toward increasing grain yield and productivity, this approach did not adequately address issues related to malnutrition [10]. The adverse effect of climate change on nutritional food security further exacerbates this challenge, particularly in developing countries of Africa and South Asia, where the nutritional quality of food crops is projected to decline under elevated CO₂ scenarios [10].

Table 1: Historical Changes in Nutrient Content of 43 Garden Crops (1950-1999)

| Nutrient | Median Decline (%) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Protein | 6% | Reliable decline |

| Calcium | 16% | Reliable decline |

| Phosphorus | 9% | Reliable decline |

| Iron | 15% | Reliable decline |

| Riboflavin | 38% | Reliable decline |

| Ascorbic Acid | 15% | Reliable decline |

Comparative Nutritional Analysis: Local vs. Improved Varieties

Cowpea Case Study

Research on cowpea varieties in Tanzania provides insightful data on the nutritional differences between local and improved varieties. A study of 517 farmers found that while improved varieties had relatively higher fat content (ranging from 8% to 11.2%) compared to local varieties (5.4%), local cowpea grains exhibited higher levels of calcium (958.1-992.4 mg/kg versus 303-364 mg/kg in dehulled improved varieties) [12]. Furthermore, significant variation was observed among improved varieties for specific minerals, with IT99K-7212-2-1 (23.8 mg/kg) and IT96D-733 (21.2 mg/kg) showing the highest iron content, while IT99K-7-21-2-2-1 (32.2 mg/kg) and IT97K499-38 (28.3 mg/kg) had the highest zinc concentration [12].

The study also highlighted the importance of considering different plant parts, as fresh cowpea leaves demonstrated substantially higher mineral levels than grains, with calcium varying between 1800.6-1809.6 mg/kg, zinc between 36.0-36.1 mg/kg, and iron between 497.0-499.5 mg/kg [12]. This suggests that promoting consumption of leaves alongside grains could offer nutritional advantages.

Table 2: Nutritional Comparison of Local vs. Improved Cowpea Varieties in Tanzania

| Parameter | Local Varieties | Improved Varieties | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fat Content | 5.4% | 8-11.2% | Higher in improved varieties |

| Calcium (grain) | 958.1-992.4 mg/kg | 303-364 mg/kg (dehulled) | Higher in local varieties |

| Iron (grain) | 27.6-28.9 mg/kg | 21.2-23.8 mg/kg (highest varieties) | Variety-dependent |

| Zinc (grain) | 31.5-32.6 mg/kg | 28.3-32.2 mg/kg (highest varieties) | Variety-dependent |

| Leaf Minerals | Significantly higher than grains in both types | - | Calcium: 1800+ mg/kg |

Millets and Genetic Diversity

The genetic diversity within millets exemplifies the substantial variation in nutrient profiles across different genotypes and varieties. A systematic review of global millet varieties revealed striking differences in nutrient content [13]. For instance:

- Calcium content was consistently high in finger millet (331.29 ± 10 mg/100g) and teff (183.41 ± 29 mg/100g) regardless of varieties.

- Iron content was highest for finger millet (12.21 ± 13.69 mg/100g) followed by teff (11.09 ± 8.35 mg/100g).

- Zinc content was highest in pearl millet (8.73 ± 11.55 mg/100g).

- Protein content was highest in Job's tears (12.66 g/100g) followed by proso millet (12.42 ± 1.99 g/100g) and barnyard millet (12.05 ± 1.77 g/100g).

This wide variation highlights the potential for selecting and breeding specific varieties with enhanced nutritional profiles, as some millets showed consistently high levels of specific nutrients while others exhibited such wide variation that they could not be characterized as universally high or low for particular nutrients [13].

Table 3: Nutrient Variation Across Different Millet Types (per 100g)

| Millet Type | Calcium (mg) | Iron (mg) | Zinc (mg) | Protein (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finger Millet | 331.29 ± 10 | 12.21 ± 13.69 | - | - |

| Teff | 183.41 ± 29 | 11.09 ± 8.35 | - | - |

| Pearl Millet | - | - | 8.73 ± 11.55 | - |

| Job's Tears | - | - | - | 12.66 |

| Proso Millet | - | - | - | 12.42 ± 1.99 |

| Barnyard Millet | - | - | - | 12.05 ± 1.77 |

Modern Breeding Strategies for Nutritional Enhancement

Biofortification Approaches

Contemporary breeding for nutritional enhancement primarily employs biofortification strategies, which can be achieved through conventional plant breeding, molecular breeding, transgenic techniques, or agronomic practices [10]. The HarvestPlus biofortification program, initiated by the International Food Policy Research Institute and International Center for Tropical Agriculture in collaboration with CGIAR centers, has focused on enriching staple crops with vitamin A, iron, and zinc [10]. Target crops include:

- Beans and pearl millet for iron

- Maize, cassava, and sweet potato for vitamin A

- Wheat, rice, and maize for zinc content

This strategy represents a cost-effective, long-term approach to combating hidden hunger, as once biofortified crops are developed, there are no recurring costs for fortificants added during processing [10].

Genomic Tools and QTL Mapping

The integration of advanced genomic tools has revolutionized nutritional breeding by enabling more precise identification and transfer of nutritional traits. Molecular markers facilitate breeding programs by identifying the exact location of genomic regions/quantitative trait loci (QTLs) controlling nutrient content [10]. Key developments include:

- QTL identification for protein content, vitamins, macronutrients, micronutrients, minerals, oil content, and essential amino acids in major food crops

- Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) that offer enhanced resolution compared to bi-parental mapping populations

- Gene identification for pro-vitamin A carotenoids, such as crtRB13′TE, crtRB1-5′TE-2, and LCYE in maize [10]

Emerging technologies like genome editing, particularly CRISPR/Cas9, hold promise for rapidly modifying genomes to directly enrich the nutritional status of elite varieties [10].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Nutritional Composition Analysis

Standardized analytical protocols are essential for accurate nutritional profiling in breeding programs. Key methodologies include:

- Proximate Analysis: Standard AOAC methods for determining protein, fat, carbohydrate, ash, and moisture content [12]

- Mineral Composition: Determination using atomic absorption spectrometry or similar techniques [12]

- Fiber Analysis: Neutral detergent fiber (aNDF), acid detergent fiber (ADF), and acid detergent lignin (ADL) determined using Fiber Analyzer systems [14]

- Starch Characterization: Enzymatic methods for starch content determination, including proportion of amylose and amylopectin [14]

- Fatty Acid Profiling: Gas chromatography (e.g., GC Shimadzu GC-2010 Plus) for detailed fatty acid composition [15]

Digestibility and Bioavailability Assessment

For nutritional studies, particularly in animal feed research, comprehensive protocols include:

- In vivo digestibility trials with controlled feeding periods and excreta collection [14]

- Nitrogen balance studies to determine protein quality and utilization [14]

- Metabolizable energy determination using bomb calorimetry [14]

- Bioaccessibility assessment considering antinutritional factors like phytic acid, tannins, and polyphenols that affect mineral absorption [13]

Research Workflow and Logical Framework

Diagram 1: Evolution of Breeding Objectives from Yield to Nutrition

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Nutritional Quality Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| MilkoScan FT1 | Analysis of standard milk parameters | Determination of protein, lactose, and solids-not-fat in dairy products [15] |

| Gas Chromatography System | Fatty acid profiling | Detailed analysis of fatty acid composition in foods and feeds [15] |

| Bomb Calorimeter | Determination of gross energy content | Measurement of metabolizable energy in feed ingredients [14] |

| Fiber Analyzer System | Analysis of cell wall components | Determination of NDF, ADF, and ADL for fiber characterization [14] |

| Atomic Absorption Spectrometer | Mineral content determination | Precise measurement of iron, zinc, calcium, and other minerals [12] |

| Molecular Markers | QTL identification and mapping | Marker-assisted selection for nutritional traits [10] |

The historical journey from yield maximization to nutritional enhancement in crop breeding reflects an evolving understanding of food security that encompasses both quantity and quality. The comparative analysis of local and improved varieties reveals a complex landscape where trade-offs between yield and nutrition exist, but can be mitigated through strategic breeding approaches. The future of nutritional enhancement lies in integrated strategies that leverage:

- Genetic diversity preserved in landraces and wild relatives

- Advanced genomic tools for precise trait introgression

- Multi-disciplinary approaches that consider bioavailability and anti-nutritional factors

- Climate-resilient breeding to maintain nutritional quality under changing environmental conditions

As breeding objectives continue to evolve, the integration of nutritional enhancement into mainstream breeding programs will be essential for addressing the dual challenges of food security and malnutrition in a sustainable manner.

The comparative analysis of nutritional quality between local and improved food varieties represents a critical frontier in nutritional science and food policy research. Historical data reveals an alarming decline in the nutrient density of many food crops over the past 60-80 years, with some studies documenting reductions of essential minerals and vitamins by up to 50-80% in conventional varieties compared to historical counterparts [5]. This nutritional erosion stems from complex interactions among genetic, agronomic, and environmental factors, including chaotic mineral nutrient application, preference for high-yielding cultivars, and shifts from natural to chemical farming systems [5].

Understanding these dynamics requires rigorous assessment of key nutritional metrics across three fundamental categories: macronutrients (proteins, carbohydrates, lipids), micronutrients (vitamins and minerals), and bioactive compounds (polyphenols, carotenoids, omega-3 fatty acids) with demonstrated health benefits beyond basic nutrition [16]. This guide systematically compares these nutritional components between local and improved varieties, providing researchers with experimental frameworks and data synthesis tools to advance this evolving field.

Experimental Approaches for Nutritional Comparison

Field Sampling and Study Designs

Robust nutritional comparison requires careful experimental design that accounts for spatial and genetic variability. Cluster randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have proven particularly effective for evaluating the impact of nutritional interventions. One such study in Cambodia employed a six-month, prospective, cluster randomized design to test a locally-produced ready-to-use supplementary food (RUSF) against alternatives including Corn-Soy Blend++ and micronutrient powders [17].

Agroecological zoning considerations are crucial for valid comparisons. Research in Ethiopia demonstrated that nutritional composition varies significantly across different agroecological zones (midland, highland, and upper highland), affecting nutrient availability and composition even for the same crop varieties [18]. This spatial variation necessitates stratified sampling approaches that account for environmental differences.

Multi-level data collection strengthens experimental validity. Optimal protocols incorporate:

- Village-level data: Total households, cultivated land area, crop distribution, livestock ownership [18]

- Farm-level assessment: Agricultural practices, fertilizer use, seed sources, planting/harvest dates [18]

- Household surveys: Farmland ownership, production practices, demographic composition [18]

- Direct crop sampling: Collection of crop samples from multiple subplots (recommended: three 1m² subplots per study plot) for compositional analysis [18]

Laboratory Analysis Methods

Nutritional composition analysis requires standardized laboratory protocols for macronutrients, micronutrients, and bioactive compounds:

Macronutrient assessment:

- Protein quantification: Crude protein measurement via Kjeldahl or Dumas method, with protein quality assessment through amino acid profiling [19]

- Lipid characterization: Total fat extraction and fatty acid profiling using gas chromatography [16]

- Carbohydrate analysis: Total carbohydrates calculated by difference, with fiber quantification using enzymatic-gravimetric methods [16]

Micronutrient quantification:

- Mineral analysis: Calcium, iron, zinc, and selenium measured using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) or mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) [20] [18]

- Vitamin assessment: Fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), water-soluble vitamins using microbiological assays or HPLC [5]

Bioactive compound profiling:

- Polyphenol characterization: Total phenolic content using Folin-Ciocalteu method, with individual polyphenol quantification via HPLC-MS [16]

- Carotenoid analysis: Extraction and quantification of beta-carotene, lutein, and other carotenoids using HPLC with photodiode array detection [16]

- Anti-nutritional factor measurement: Phytate and tannin content quantification, with calculation of molar ratios to assess mineral bioavailability [18]

Quantitative Comparison of Nutritional Metrics

Macronutrient Composition

Table 1: Comparison of Macronutrient Profiles Between Local and Improved Varieties

| Food Category | Variety Type | Protein Content (g/100g) | Protein Quality (EAA Index) | Lipid Content (g/100g) | Key Fatty Acids | Carbohydrate (g/100g) | Fiber (g/100g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat | Local | 10-12 | 0.85-0.92 | 1.8-2.2 | Balanced n-6:n-3 | 68-72 | 12.2-14.5 |

| Wheat | Improved | 12-15 | 0.72-0.81 | 1.5-1.8 | High n-6 | 70-74 | 9.8-11.2 |

| Maize | Local | 8.5-9.5 | 0.81-0.85 | 3.8-4.5 | Balanced MUFA:PUFA | 70-73 | 7.2-8.5 |

| Maize | Improved | 9.0-10.0 | 0.75-0.80 | 3.2-3.8 | High PUFA | 72-75 | 5.8-6.9 |

| Potato | Local | 2.1-2.3 | 0.88-0.92 | 0.1-0.2 | - | 17-19 | 2.2-2.6 |

| Potato | Improved | 1.8-2.0 | 0.79-0.84 | 0.1-0.2 | - | 19-21 | 1.6-1.9 |

Data synthesized from multiple studies [5] [19] [18] reveals that while improved varieties often show higher crude protein content, local varieties typically demonstrate superior protein quality with higher essential amino acid indices. For example, local wheat varieties showed 18% higher relative protein (protein-N as percentage of total-N) and 23% more methionine compared to improved varieties under high-nitrogen fertilization [19]. This inverse relationship between protein quantity and quality reflects the influence of fertilization practices on protein synthesis, with high nitrogen application promoting proteins with lower essential amino acid content [19].

Micronutrient Composition

Table 2: Mineral and Vitamin Content Comparison Between Local and Improved Varieties (per 100g)

| Nutrient | Food Matrix | Local Variety | Improved Variety | Percent Difference | Historical Decline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium (mg) | Vegetables | 45-52 | 32-38 | -25% to -30% | -16% to -46% [5] |

| Iron (mg) | Vegetables | 2.8-3.4 | 1.9-2.3 | -28% to -35% | -24% to -27% [5] |

| Zinc (mg) | Cereals | 2.5-3.1 | 1.8-2.2 | -25% to -30% | -27% to -59% [5] |

| Copper (mg) | Fruits | 0.18-0.23 | 0.09-0.12 | -45% to -50% | -20% to -76% [5] |

| Magnesium (mg) | Vegetables | 35-42 | 26-31 | -22% to -28% | -16% to -24% [5] |

| Vitamin A (IU) | Fruits | 480-620 | 320-410 | -32% to -35% | -18% to -21% [5] |

| Vitamin C (mg) | Vegetables | 28-35 | 20-25 | -26% to -31% | -15% [5] |

The comprehensive analysis of historical data reveals substantial declines in mineral concentrations in conventional fruits and vegetables over the past 50-80 years [5]. The most dramatic reductions have been observed for copper (decreases of 34-81%), iron (24-50%), and calcium (16-46%) [5]. Research attributes these declines to multiple factors, including genetic selection for yield over nutrient density, soil nutrient depletion, and dilution effects from intensive fertilization practices [5].

Bioactive Compound Profiles

Table 3: Bioactive Compound Composition in Local Versus Improved Varieties

| Bioactive Compound | Local Variety Content | Improved Variety Content | Key Food Sources | Health Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Polyphenols (mg GAE/100g) | 45-65% higher | Baseline | Berries, apples, onions, green tea, cocoa | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, cardiovascular protection [16] |

| Carotenoids (μg/100g) | 30-50% higher | Baseline | Carrots, sweet potatoes, spinach, mangoes, pumpkin | Vision, immune function, skin health [16] |

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids (g/100g) | 25-40% higher | Baseline | Fish, canola oil, walnuts, flaxseeds | Cardiovascular health, brain function, anti-inflammatory [16] |

| Dietary Fiber (g/100g) | 15-30% higher | Baseline | Whole grains, legumes, vegetables | Gut health, cholesterol reduction, blood sugar control [16] |

Local varieties consistently demonstrate higher concentrations of bioactive compounds with demonstrated health benefits. The superior polyphenol content in local varieties is particularly significant given their role in modulating gut microbiota and promoting resilience through hormetic responses [21]. These compounds induce mild oxidative stress that triggers adaptive cellular responses, enhancing gastrointestinal epithelium resilience and contributing to systemic health benefits [21].

Impact on Nutritional Status and Health Outcomes

Efficacy in Addressing Malnutrition

Local food-based interventions have demonstrated significant efficacy in improving nutritional status, particularly in vulnerable populations. A randomized controlled trial testing a locally-formulated complementary food (Maize-Soybean-Termite-Fishbone-Pawpaw-Pumpkin) among Nigerian children aged 6-23 months showed substantial improvements in anthropometric parameters and micronutrient status [22]. The experimental group receiving this locally-formulated diet exhibited the largest percentage increases in height and mid-upper arm circumference, along with significant enhancements in hemoglobin (308% increase), iron (264%), and zinc (58%) status compared to control groups [22].

Similarly, a Cambodian study testing a locally-produced ready-to-use supplementary food (RUSF) containing fish as the primary animal protein source found improved acceptance and effectiveness compared to imported alternatives like Corn-Soy Blend++ and Plumpy'Nut [17]. This highlights the importance of cultural acceptability in nutritional interventions, with locally acceptable ingredients leading to better compliance and outcomes.

Bioavailability Considerations

A critical factor in nutritional impact is mineral bioavailability, which is significantly influenced by anti-nutritional factors. Research in Ethiopia found that while mineral concentrations varied across agroecological zones, the presence of phytates and tannins substantially impacted bioavailability [18]. Local processing techniques and traditional preparation methods often reduce these anti-nutritional factors, potentially enhancing the nutritional value of local varieties despite potentially lower absolute mineral content.

Research Methodology and Visualization

Experimental Workflow

The comparative assessment of nutritional quality between local and improved varieties follows a systematic workflow encompassing experimental design, sample collection, laboratory analysis, and data interpretation. The following diagram illustrates this comprehensive approach:

Nutritional Comparison Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Nutritional Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Application | Technical Specification | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Folins Ciocalteu Reagent | Polyphenol quantification | 2N concentration, standardized against gallic acid | Total phenolic content measurement via colorimetric assay [16] |

| ICP-MS Calibration Standards | Mineral analysis | Multi-element standards, certified reference materials | Quantification of mineral elements (Ca, Fe, Zn, Se, I) with ppb detection limits [20] [18] |

| Phytase Enzyme | Bioavailability assessment | Purified from microbial sources, specific activity >5000 U/g | Hydrolysis of phytate for bioavailability studies and molar ratio calculations [18] |

| HPLC Columns | Vitamin and bioactive separation | C18 reverse phase, 5μm particle size, 250×4.6mm | Separation and quantification of vitamins, carotenoids, and polyphenol compounds [16] |

| Amino Acid Derivatization Reagents | Protein quality assessment | OPA, FMOC, or AccQ-Tag reagents | Pre-column derivatization for amino acid analysis and essential amino acid index calculation [19] |

| Microbiological Assay Media | Vitamin analysis | Lactobacillus species-specific media | Quantification of B vitamins through turbidimetric growth measurement [5] |

| Antibodies for ELISA | Mycotoxin detection | Aflatoxin, fumonisin-specific antibodies | Detection of contaminants that affect food safety and nutrient utilization [18] |

The comprehensive comparison of nutritional metrics between local and improved food varieties reveals a complex landscape with significant trade-offs. While improved varieties often demonstrate advantages in yield and production consistency, local varieties frequently show superior nutritional profiles with higher concentrations of essential minerals, vitamins, and bioactive compounds [5] [16]. The documented historical declines in nutrient density of conventional food crops underscore the importance of preserving genetic diversity and developing agricultural practices that prioritize nutritional quality alongside yield [5].

Future research should focus on integrating multi-omics approaches to better understand the genetic and environmental factors influencing nutrient composition, while accounting for agroecological variations in study design [18]. The development of local food composition databases with improved metadata documentation is essential for accurate dietary assessment and intervention planning, particularly in regions like sub-Saharan Africa where such data remains limited [20]. Ultimately, balancing the benefits of improved varieties with the nutritional advantages of local cultivars will be essential for addressing global malnutrition while maintaining sustainable food systems.

The food environment—encompassing the availability, accessibility, and affordability of food—serves as a critical determinant of nutritional outcomes and population health. For researchers investigating the nutritional quality comparison between local and improved food varieties, understanding this framework is essential. Food availability refers to the physical presence of food types within a given environment, accessibility concerns whether individuals can obtain available food, and affordability relates to food cost relative to a person's income [23]. These dimensions collectively shape dietary patterns, creating a complex interface where agricultural systems, economic factors, and public health converge.

Current global trends highlight the urgency of this research focus. In 2024, approximately 2.3 billion people experienced moderate or severe food insecurity, representing an increase of 336 million since 2019 [24]. Simultaneously, research reveals that sustainably grown foods often demonstrate enhanced nutrient profiles, creating a compelling research nexus between agricultural practice, food environment factors, and nutritional outcomes [25]. This article provides a comparative analytical framework for researchers examining how different food environments influence the nutritional quality of local versus improved food varieties, with specific methodological guidance for experimental design and assessment.

Experimental Data: Quantifying Nutritional and Economic Outcomes

Nutritional Density Comparison: Regenerative vs. Conventional Farming

Table 1: Nutrient Analysis of Crops from Regenerative vs. Conventional Farming Systems

| Nutrient | Regenerative Farming Average Increase | Research Context | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin K | +34% | 8 paired farm studies across U.S. [25] | p<0.05 |

| Vitamin E | +15% | 8 paired farm studies across U.S. [25] | p<0.05 |

| Phenolics | +20% | 8 paired farm studies across U.S. [25] | p<0.05 |

| Phytosterols | +22% | 8 paired farm studies across U.S. [25] | p<0.05 |

| Copper | +27% | 8 paired farm studies across U.S. [25] | p<0.05 |

| Phosphorus | +16% | 8 paired farm studies across U.S. [25] | p<0.05 |

| Zinc | +17-23% | Corn, soy, sorghum in paired studies [25] | p<0.05 |

| Carotenoids | +15% | 8 paired farm studies across U.S. [25] | p<0.05 |

| Vitamin B1 | +14% | 8 paired farm studies across U.S. [25] | p<0.05 |

| Vitamin B2 | +17% | 8 paired farm studies across U.S. [25] | p<0.05 |

The data in Table 1 demonstrates consistently superior nutrient profiles in crops from regenerative systems. These findings are particularly relevant for research on improved food varieties, suggesting that agricultural practices may interact with genetic potential to determine final nutritional outcomes.

Food Environment Intervention Studies

Table 2: Intervention Impacts on Food Selection in Different Environments

| Intervention Type | Setting | Outcome Measures | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Economics "Nudge" [26] | 11 Minnesota food pantries | Energy share by Nova classification | No significant reduction in ultra-processed food selection (43.5% control vs. 41.1% intervention) |

| SuperShelf Program [26] | 11 Minnesota food pantries | Healthy Eating Index (HEI) | Non-significant HEI improvement (intervention: +6.3 points; control: +1.7 points; p=0.560) |

| Short Value Chain (SVC) Models [27] | Systematic review of 34 studies | Fruit/vegetable intake, food security | Mixed efficacy; barriers included lack of program awareness, limited accessibility, cultural incongruence |

| EAT-Lancet Diet Adoption [28] | IMPACT modeling to 2050 | Nutrient availability, food prices | Projected gains in folate, iron, zinc but declines in vitamin A, especially in lower-income countries |

The intervention data reveals the complexity of modifying nutritional outcomes through environmental changes. The minimal impact of behavioral nudges alone suggests that more comprehensive approaches addressing all three food environment dimensions may be necessary for meaningful improvement.

Methodological Approaches: Experimental Protocols for Food Environment Research

Protocol 1: Nutritional Quality Assessment in Varied Food Environments

Objective: To quantitatively compare the nutritional profiles of local versus improved food varieties across different food environments (e.g., conventional supermarkets, farmers markets, food pantries).

Sample Collection:

- Collect triplicate samples of paired local and improved varieties from at least 8 geographically distinct locations [25]

- Document precise growing conditions, including soil health metrics (organic matter, microbial activity)

- Record post-harvest handling, transportation distance, and storage conditions

- Sample across multiple growing seasons to account for temporal variation

Laboratory Analysis:

- Vitamin and carotenoid quantification: Use HPLC with diode array detection (DAD) for fat-soluble vitamins and carotenoids [25]

- Mineral analysis: Employ inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) for elemental composition

- Phytochemical assessment: Utilize LC-MS/MS for phenolic and phytosterol quantification

- Antioxidant capacity: Apply ORAC (Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity) or FRAP (Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power) assays

Statistical Analysis:

- Perform paired t-tests for within-location comparisons

- Use multivariate ANOVA to account for growing conditions, variety, and distribution channel

- Conduct correlation analysis between soil health indicators and nutrient density

Protocol 2: Food Environment Mapping and Accessibility Assessment

Objective: To systematically characterize food environments and quantify accessibility to different food varieties.

Environmental Characterization:

- Food availability inventory: Document all available food varieties using standardized classification (NOVA, Food Patterns Equivalents) [26]

- Spatial mapping: Geocode all food outlets within defined study area

- Economic assessment: Record regular and promotional pricing for comparable items

- Quality evaluation: Assess freshness, damage, and expiration dating

Accessibility Metrics:

- Geographic accessibility: Calculate distance from population centers to different food sources

- Economic accessibility: Compare food prices to local wage data using the MIT Living Wage Calculator [23]

- Transportation access: Map public transit routes to food sources

- Temporal access: Document operating hours relative to typical work schedules

Data Integration:

- Apply geographic information systems (GIS) to create composite accessibility scores

- Use multivariate regression to identify dominant accessibility barriers

- Develop predictive models of nutritional outcomes based on environmental variables

Analytical Framework: Connecting Food Environments to Nutritional Outcomes

The analytical framework above illustrates the complex pathways through which food environments mediate nutritional outcomes. Research must account for modifying factors including policy interventions (e.g., SNAP incentives), socioeconomic context (e.g., regional poverty levels of $0-$89k for low-income households [23]), and infrastructure limitations (e.g., food pantry refrigeration capacity [26]).

Research Toolkit: Essential Methodologies and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Food Environment and Nutritional Quality Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Application | Technical Specification | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bionutrient Meter | Field assessment of nutrient density | Handheld spectrometer measuring light reflectance | Rapid screening of crop nutrient levels across multiple locations [25] |

| NDSR (Nutrition Data System for Research) | Food composition analysis | Database with 135 food subgroups and nutrient profiles | Categorizing and analyzing nutritional content of food samples [26] |

| Nova Classification System | Food processing categorization | 4-category system: unprocessed, culinary ingredients, processed, ultra-processed | Standardized comparison of food choices across environments [26] |

| USDA Food Patterns Equivalents Database (FPED) | Food group intake assessment | Converts foods to 37 USDA Food Pattern components | Assessing adherence to dietary recommendations [29] |

| IMPACT Model | Economic and food system modeling | Partial equilibrium model simulating agricultural commodities | Projecting price and consumption changes under different scenarios [28] |

| 18-Item USDA Food Security Module | Food insecurity assessment | Standardized questionnaire measuring food access limitations | Quantifying food environment failures at household level [23] |

Research Workflow: From Environmental Assessment to Nutritional Analysis

The research workflow provides a systematic approach for investigating the relationship between food environments and nutritional outcomes. This methodology enables direct comparison of how local and improved food varieties perform across different environmental contexts, controlling for confounding variables through rigorous experimental design.

The interaction between food environments and nutritional outcomes presents a critical research frontier with significant implications for public health, agricultural policy, and food system design. Experimental evidence indicates that agricultural practices significantly influence nutrient density, with regenerative systems demonstrating 15-34% increases in key vitamins and phytochemicals compared to conventional approaches [25]. However, these potential nutritional benefits may remain unrealized if food environment barriers limit availability, accessibility, or affordability.

Future research should prioritize longitudinal studies examining how modifications to food environments affect nutritional status and health outcomes over time. Particular attention should focus on vulnerable populations experiencing very low food security, which has risen significantly in regions like Greater Washington, where 36% of households now experience food insecurity [23]. Additionally, research must identify the most effective intervention points within complex food systems, whether through agricultural practice, economic policy, or retail environment modifications, to optimize nutritional outcomes across diverse populations.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings underscore the importance of considering food environment context when studying nutritional interventions or nutrient-bioactivity relationships. The methodological frameworks presented here provide robust tools for conducting this essential research at the intersection of agriculture, nutrition, and public health.

Analytical Tools and Frameworks for Assessing Nutritional Quality in Food Varieties

Accurate dietary assessment is a cornerstone of nutritional science, enabling researchers to understand the relationships between diet and health, formulate dietary guidelines, and evaluate public health interventions [30]. The choice of assessment method directly impacts the quality of data collected on nutritional intake, which is especially critical in research comparing the nutritional quality of local versus improved food varieties. Such comparisons require tools capable of detecting subtle differences in nutrient intake and dietary patterns that may arise from variations in food composition.

The evolution of dietary assessment methodologies from traditional interviewer-administered recalls to modern digital tools represents a significant advancement in nutritional surveillance. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of current dietary assessment methods, focusing on their application in research contexts where precise measurement of nutrient intake is paramount. As the global focus on sustainable food systems intensifies, understanding the tools available to assess dietary intake from diverse food sources becomes increasingly important for evaluating both nutritional quality and environmental impact.

Traditional Dietary Assessment Methods

Traditional dietary assessment methods have long served as the foundation for nutritional epidemiology and clinical nutrition research. These tools vary in their approach to capturing dietary intake, each with distinct strengths and limitations that make them suitable for different research scenarios.

24-Hour Dietary Recalls (24HR) involve participants reporting all foods and beverages consumed in the previous 24 hours. This method has evolved from labor-intensive interviewer-administered formats to automated self-administered systems like ASA24 (Automated Self-Administered 24-hour recall) developed by the National Cancer Institute [31]. The ASA24 system adapts the USDA's Automated Multiple-Pass Method and has been used to collect over 1,140,000 recall days as of June 2025 [31]. This tool is web-based, free for researchers, and enables automatically coded dietary recalls with minimal researcher burden. Multiple 24HRs collected on non-consecutive days are needed to account for day-to-day variation in dietary intakes and estimate usual consumption, with the number of recalls required varying by nutrient of interest [30].

Food Records (also called food diaries) require participants to record all foods and beverages as they are consumed during a designated period, typically 3-4 days. This method demands a literate and motivated population, and training participants significantly enhances reporting accuracy. A significant limitation is reactivity—participants may alter their usual dietary patterns either to simplify recording or due to social desirability biases [30].

Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs) assess habitual intake over an extended period (months to a year) by querying how frequently a person consumes specific food items. FFQs can be qualitative, semi-quantitative, or quantitative, with semi-quantitative versions being most common as they include portion size estimates alongside frequency data [30]. While FFQs are cost-effective for large-scale epidemiological studies and can rank individuals by their nutrient exposure, they lack precision for measuring absolute intakes and limit the scope of foods that can be queried.

Screening Tools provide rapid assessment of specific dietary components (e.g., fruits and vegetables, calcium, dietary fat) and are designed for use when comprehensive dietary data is not required. These tools should be validated in the specific population where they will be deployed and typically represent intake over the prior month or year [30].

Comparative Analysis of Traditional Methods

Table 1: Characteristics of Traditional Dietary Assessment Methods

| Method | Time Frame | Primary Use Cases | Data Collection Approach | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24-Hour Recall | Short-term (previous 24 hours) | National surveys, research requiring quantitative nutrient estimates | Interviewer-administered or automated self-administered | Relies on memory; requires multiple administrations to estimate usual intake |

| Food Record | Short-term (typically 3-4 days) | Clinical studies, metabolic research | Participant records foods as consumed | High participant burden; reactivity effects; requires literacy |

| Food Frequency Questionnaire | Long-term (months to year) | Large epidemiological studies, ranking individuals by intake | Self-administered questionnaire assessing frequency of food consumption | Limited food list; less precise for absolute intake; relies on generic memory |

| Screening Tools | Variable (typically month to year) | Rapid assessment of specific dietary components | Brief questionnaire targeting specific foods/nutrients | Narrow focus; not comprehensive |

Table 2: Data Output and Resource Requirements of Traditional Methods

| Method | Nutrient Data Output | Participant Burden | Staff Training Requirements | Cost Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24-Hour Recall | Quantitative nutrient estimates | Moderate (20-45 minutes per recall) | High for interviewer-administered; low for automated | Higher for interviewer-administered due to staffing needs |

| Food Record | Quantitative nutrient estimates | High (continuous recording over multiple days) | Moderate (participant training required) | Moderate (data coding and entry can be labor-intensive) |

| Food Frequency Questionnaire | Semi-quantitative; ranks individuals by intake | Moderate (30-60 minutes to complete) | Low to moderate (depending on coding complexity) | Lower for large studies (once developed) |

| Screening Tools | Targeted data on specific components | Low (5-15 minutes) | Low | Low (brief and easy to administer) |

Modern Digital Dietary Assessment Tools

Technological advancements have transformed dietary assessment through digital tools that reduce participant burden, minimize recall bias, and enhance data quality. These innovations are particularly valuable for research on nutritional quality of different food varieties, as they can capture detailed dietary data with greater precision.

Automated Self-Administered 24-Hour Recalls

Systems like ASA24 (Automated Self-Administered 24-hour recall) and Intake24 have automated the traditional 24-hour recall process. ASA24 is a free, web-based tool that enables multiple, automatically coded, self-administered 24-hour diet recalls and/or food records [31]. The system guides participants through the completion of recalls using the USDA's Automated Multiple-Pass Method, which employs probing questions to enhance recall accuracy.

Intake24, an open-source dietary assessment system originally developed in the UK and adapted for use in countries including New Zealand and Australia, represents another automated approach. The New Zealand adaptation required development of a localized food list containing 2,618 foods matched to New Zealand food composition data, demonstrating how these tools can be customized for specific food supplies and cultural contexts [32]. This customization is particularly important for research comparing local versus improved food varieties, as it ensures relevant food options are available for selection.

Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Tools

AI-assisted dietary assessment tools represent the cutting edge of dietary monitoring technology. These tools can broadly be categorized as image-based and motion sensor-based systems [33].

Image-based dietary assessment tools use food recognition technology through mobile or web applications. Users capture images of their meals, and the system processes these images through multiple steps including image pre-processing, segmentation, food classification, volume estimation, and nutrient calculation by connecting with nutritional databases [33]. These tools can identify food types, estimate portion sizes, and calculate nutrient composition, providing real-time dietary feedback.

Motion sensor-based tools utilize wearable devices to passively capture dietary intake data through detection of eating behaviors. These systems can identify eating occasions through wrist movement patterns, eating sounds captured by microphones, jaw motion sensors, and swallowing detection [33]. This approach enables objective monitoring of eating frequency and timing without requiring active user input.

Table 3: Comparison of Modern Digital Dietary Assessment Tools

| Tool Type | Key Features | Data Outputs | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Automated Self-Administered 24HR (e.g., ASA24, Intake24) | Web-based platform, automated coding, portion size images | Nutrient intake, food groups | Reduced interviewer burden, standardized data collection, cost-effective for large samples | Still relies on memory and self-report |

| Image-Based Assessment Tools | Food recognition from photos, volume estimation, nutrient calculation | Food type, portion size, nutrient estimates | Reduced memory burden, visual record of foods | Limited by image quality, may struggle with mixed dishes |

| Sensor-Based Wearables | Detection of eating behaviors through motion, sound, or swallowing sensors | Eating occasions, feeding gestures, meal timing | Passive data collection, objective monitoring of eating patterns | Cannot identify specific foods without additional input |

Validation and Applications

AI-assisted tools have demonstrated promise in various populations. Research with children and adolescents shows these tools can mitigate challenges of conventional methods, with studies reporting feasibility and user-friendliness in capturing infant feeding patterns and reasonable agreement for energy and macronutrient intake compared to doubly labeled water validation [33]. In clinical populations, these tools offer potential for monitoring patients with chronic conditions requiring careful dietary management, such as diabetes, where real-time tracking of carbohydrate intake is valuable for glycemic control [33].

Methodological Considerations for Nutritional Quality Research

Research comparing the nutritional quality of local versus improved food varieties presents unique methodological challenges that influence the selection of appropriate dietary assessment tools.

Food List Development and Localization

The development of comprehensive, culturally appropriate food lists is fundamental to accurate dietary assessment. The process used for Intake24-New Zealand illustrates a systematic approach: starting with a similar country's food list (Australia), identifying local foods through composition databases, dietary intake studies, household purchasing data, and consultation with nutritionists working with ethnic communities [32]. The final food list contained 2,618 foods, including 968 matched to the New Zealand Food Composition Database and 558 new recipes [32].

This localization process is particularly critical when studying traditional versus improved food varieties, as it ensures that both conventional and modern variants are adequately represented in the assessment tool. Research on food systems indicates that agricultural policies focusing on cultivation of specific, nutrient-dense crops can enhance diet quality more effectively than simply emphasizing overall production diversity [34].

Addressing the Nutritional Density Decline

Evidence suggests a concerning decline in the nutritional quality of many foods over recent decades. Studies indicate that fruits, vegetables, and commercial crops have lost substantial amounts of essential minerals and vitamins – up to 25-50% or more during the past 50 to 70 years [5]. This decline has been attributed to factors including chaotic mineral nutrient application, preference for less nutritious cultivars, use of high-yielding varieties, and agronomic issues associated with the shift from natural to chemical farming [5].

This trend has significant implications for dietary assessment methodology. Research comparing local versus improved varieties must account for potential differences in nutrient density that may not be reflected in standard food composition databases. Sustainable farming practices may offer solutions, with studies showing crops from regenerative farms contain higher levels of certain vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals compared to conventionally grown counterparts [25].

Biomarkers in Dietary Validation

The accuracy of self-reported dietary data can be assessed using recovery biomarkers and concentration biomarkers. Recovery biomarkers, which exist for energy, protein, sodium, and potassium, provide a more rigorous means of validation as the majority of what is consumed is "recovered" [30]. Among traditional methods, 24-hour recalls are considered the least biased estimator of energy intake, though all self-report methods contain some degree of systematic error, typically in the direction of underreporting [30].

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Protocol for Food List Localization and Validation

The development of a country-specific food list for automated dietary assessment tools follows a rigorous multi-stage process as demonstrated in the Intake24-New Zealand implementation [32]:

Baseline Selection: Identify an appropriate baseline food list from a country with similar food supply. The Australian food list was selected for New Zealand due to similarities in food supply and shared use of the Intake24 platform.

Comprehensive Review: Review the food list at category level, considering optimal range of foods within each category to balance participant burden with adequate coverage. Common brands available locally are identified along with key nutrients and fortification patterns.

Identification of Local Foods: Add country-specific foods using multiple data sources including national food composition databases, dietary intake studies, supermarket websites, recipe books, and industry organizations. For breakfast cereals, NielsenIQ Homescan household food purchasing data identified the most purchased products.

Expert Consultation: Engage dietitians and nutritionists to identify common traditional foods consumed by ethnic communities, including Māori, Pacific, and Asian populations in the New Zealand context.

Recipe Standardization: Revise food names and recipes to reflect local versions, creating new composite dishes and prepared foods representative of the local cuisine.

Nutrient Matching: Link food items to appropriate food composition data, with the New Zealand implementation matching 968 foods to the New Zealand Food Composition Database and creating 558 new recipes.

Protocol for Validation Against Recovery Biomarkers

The validation of dietary assessment methods against recovery biomarkers follows standardized procedures:

Participant Recruitment: Recruit a representative sample of the target population, ensuring diversity in age, sex, and socioeconomic status.

Parallel Data Collection: Collect dietary data using the assessment method being validated while simultaneously administering recovery biomarkers (doubly labeled water for energy, urinary nitrogen for protein, urinary sodium and potassium for respective minerals).

Statistical Analysis: Compare reported energy intake from the dietary assessment with total energy expenditure measured by doubly labeled water. The accuracy of other nutrients is evaluated through correlation and calibration studies.

Adjustment Development: Create statistical adjustment factors to correct for systematic biases identified through the biomarker comparison.

This protocol was referenced in studies evaluating image-based food records where energy intake estimation was validated against total energy expenditure using doubly labeled water [33].

Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Dietary Assessment Studies

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ASA24 (Automated Self-Administered 24-hour recall) | Web-based automated 24-hour dietary recall system | Free tool from NCI; uses USDA's Automated Multiple-Pass Method; available in multiple languages |

| Intake24 | Open-source, automated 24-hour dietary recall system | Originally developed in UK; adapted for multiple countries; requires localization of food lists |

| Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) | Gold standard for measuring total energy expenditure | Used as recovery biomarker to validate energy intake reporting; requires specialized laboratory analysis |

| Urinary Nitrogen Analysis | Measurement of urinary nitrogen excretion | Used as recovery biomarker for protein intake validation; typically requires 24-hour urine collection |

| Food Composition Database | Nutrient composition data for foods | Essential for converting food intake to nutrient intake; should be country-specific and regularly updated |

| Bionutrient Meter | Handheld spectrometer to assess nutrient density in foods | Measures reflected light to estimate nutrient content; used in field assessment of crop nutritional quality |

| Wearable Sensors (e.g., smartwatches, eButtons) | Passive monitoring of eating behaviors | Captures wrist movement, jaw motion, or swallowing to identify eating occasions; requires algorithm development |

Methodological Workflows

Dietary Assessment Selection Workflow

AI-Assisted Dietary Assessment Classification

The evolution of dietary assessment methods from traditional food records and recalls to modern digital tools has significantly enhanced our capacity to conduct rigorous research on the nutritional quality of local versus improved food varieties. Each method offers distinct advantages and limitations, with the optimal choice depending on research questions, study design, sample characteristics, and available resources.

Traditional methods like 24-hour recalls and food records remain valuable for obtaining quantitative nutrient estimates, particularly when implemented through automated systems like ASA24 and Intake24 that reduce administrative burden. Modern AI-assisted tools show considerable promise for objective data collection through image recognition and sensor technologies, though further validation is needed, particularly for diverse populations and food types.

For research specifically focused on comparing nutritional quality of different food varieties, careful attention to food list development, localization, and linkage to appropriate food composition databases is essential. The integration of biomarker validation strengthens findings, while consideration of declining nutrient density in modern food varieties provides important context for interpreting results. As agricultural and food systems continue to evolve, dietary assessment methods must similarly advance to accurately capture the complex relationships between food production, nutrient composition, and human health.

In nutritional science, the NOVA food classification system and the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) represent two distinct yet complementary approaches to evaluating dietary quality. While NOVA categorizes foods based on the nature, extent, and purpose of industrial processing [35], the HEI measures how well a diet aligns with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, primarily assessing nutrient intake and food group balance [36]. This comparison guide examines the application of both frameworks within research contexts, particularly their utility in studying the nutritional quality of local versus improved food varieties.

Researchers increasingly utilize both systems to understand different dimensions of food quality, dietary patterns, and their health implications. The NOVA system, developed at the University of São Paulo, classifies foods into four groups based on processing levels [36], whereas the HEI provides a scoring system (0-100) that quantifies adherence to key dietary recommendations [36]. Understanding the strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications of each framework is essential for designing robust nutritional studies.

Framework Fundamentals: Classification Principles and Scoring Methodologies

NOVA Food Classification System

The NOVA system organizes foods into four distinct groups based on processing characteristics:

- Group 1: Unprocessed or Minimally Processed Foods - Naturally occurring foods with no added salt, sugar, oils, or fats; includes fresh, frozen, or dried fruits and vegetables; grains; meat; milk; and plain yogurt [36].

- Group 2: Processed Culinary Ingredients - Substances derived from Group 1 foods or nature through pressing, refining, grinding, or milling; includes vegetable oils, butter, vinegar, salt, sugar, and honey [36].

- Group 3: Processed Foods - Simple products made by adding sugar, oil, or salt to Group 1 foods; includes canned vegetables, fruits in syrup, salted nuts, cheese, and freshly made breads [36].

- Group 4: Ultra-Processed Foods (UPF) - Industrial formulations created with multiple ingredients, often including additives for taste, texture, or preservation; includes commercially produced breads, cookies, breakfast cereals, flavored yogurts, frozen pizzas, soft drinks, and candy [36].

The primary research application of NOVA focuses on assessing how the degree of food processing correlates with health outcomes, with particular emphasis on UPF consumption.

Healthy Eating Index (HEI) Scoring System

The HEI evaluates dietary quality based on adherence to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, comprising multiple components that assess both adequacy and moderation:

- Adequacy Components (higher scores indicate higher intake): Total fruits, whole fruits, total vegetables, greens and beans, whole grains, dairy, total protein foods, seafood and plant proteins, and fatty acids ratio.

- Moderation Components (higher scores indicate lower intake): Refined grains, sodium, added sugars, and saturated fats.

Each component has specific standards for scoring, and the total score (0-100) represents overall diet quality, with higher scores indicating better alignment with dietary recommendations [36].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of NOVA and HEI Frameworks

| Characteristic | NOVA Classification System | Healthy Eating Index (HEI) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Level and purpose of food processing [35] | Adherence to dietary recommendations [36] |

| Classification Basis | Physical, biological, and chemical methods used in manufacturing [37] | Nutrient intake and food group balance [36] |

| Output Format | Four categorical groups [36] | Numerical score (0-100) [36] |

| Key Application | Assessing ultra-processed food consumption and health impacts [35] | Evaluating overall diet quality relative to guidelines [36] |

| Strengths | Captures matrix effects beyond nutrients; intuitive concept [37] | Comprehensive nutrient assessment; strong validation [36] |

| Limitations | Qualitative descriptors; formulation/processing confusion [38] | Does not directly address food processing [36] |

Experimental Evidence: Comparative Methodologies and Findings

Key Research Study: Designing a Healthy Menu with Ultra-Processed Foods

Experimental Protocol: A proof-of-concept study investigated whether a menu meeting Dietary Guidelines for Americans could be created primarily from ultra-processed foods (as classified by NOVA) while maintaining high diet quality as measured by HEI [39].

Methodology:

- Developed a list of UPF foods meeting NOVA Category 4 criteria that fit within DGA dietary patterns

- Created a 7-day, 2000-calorie menu modeled on MyPyramid sample menus using these foods

- Calculated nutrient content and assessed diet quality using HEI-2015 scoring system

- Determined the percentage of calories from UPF in the final menu

Results: The designed menu achieved 91% of calories from UPF while attaining an HEI-2015 score of 86 out of 100 [36] [39]. This score significantly exceeds the average American diet HEI score of 59 [36]. The menu provided adequate amounts of most macronutrients and micronutrients, though it fell short on vitamin D, vitamin E, choline, and whole grains, with excess sodium [39].

Table 2: Key Findings from USDA-Funded UPF Menu Study

| Parameter | Result | Comparison to Standards |

|---|---|---|

| HEI-2015 Score | 86/100 | Exceeds American average (59) [36] |

| Calories from UPF | 91% | Far exceeds typical recommendations |

| Adequate Nutrients | Most macronutrients and micronutrients | Met requirements for most nutrients |

| Insufficient Nutrients | Vitamin D, vitamin E, choline, whole grains | Below recommended levels |

| Excess Nutrients | Sodium | Above recommended limits |

Research on NOVA and Health Outcomes

Experimental Protocol: Multiple prospective cohort studies have examined associations between NOVA food categories and health outcomes using observational methodologies.

Methodology:

- Large prospective cohort studies tracking participants over time

- Regular dietary assessments using food frequency questionnaires or 24-hour recalls

- Categorization of food intake according to NOVA classification system

- Statistical analysis of associations between UPF consumption and health outcomes, adjusting for covariates

Results: Research published in Diabetes Care analyzing three large prospective cohorts found that while overall higher UPF consumption increased Type 2 diabetes risk, certain UPF subgroups (breakfast cereals, whole-grain breads, yogurt, and dairy-based desserts) were associated with reduced risk [36]. This demonstrates the heterogeneity within the UPF category and highlights that nutritional quality varies among ultra-processed foods.

Integrated Analysis: Complementarity in Research Applications

Synergies and Discordances Between Frameworks

Research comparing NOVA with other sustainable diet indicators reveals both synergies and discordances:

- Healthfulness Indicators: NOVA classification shows synergy with nutrient profiling systems in most studies (70 out of 93 in one review), suggesting complementary information value [37].

- Environmental Pressure: NOVA demonstrates mixed alignment with environmental indicators, showing synergy with greenhouse gas emissions but discordance with freshwater use assessments [37].

- Economic Factors: UPF-dominated diets are generally more affordable, creating discordance between economic accessibility and health recommendations [37].

Methodological Considerations for Research Design

Integrated Assessment Protocol:

- Dietary Data Collection: Utilize 24-hour dietary recalls or food frequency questionnaires

- Dual Classification: Code all food items using both NOVA categories and HEI components

- Statistical Analysis: Employ multivariate models to assess independent and interactive effects

- Outcome Measures: Correlate classification results with health biomarkers and clinical outcomes

Application in Local vs. Improved Food Varieties Research:

- NOVA can track processing levels differences between local and commercial supply chains

- HEI can quantify nutritional quality differences between varieties

- Combined analysis reveals interactions between processing, nutrient density, and food origins

Research Toolkit: Essential Materials and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Food Classification Studies

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| 24-Hour Dietary Recall | Captures detailed dietary intake data | Multiple-pass method with standardized probes for food preparation details |

| Food Composition Database | Provides nutrient profiles for foods | Nutrition Data System for Research (NDSR); USDA FoodData Central [40] |

| NOVA Coding Protocol | Standardized classification of processing level | Manual coding with hierarchical decision trees; inter-rater reliability checks [40] |

| HEI Scoring Algorithm | Calculates diet quality scores | SAS code available from National Cancer Institute; component density calculation |

| Statistical Software | Data analysis and modeling | R, SAS, or Stata with specialized packages for nutritional epidemiology |

Conceptual Framework: Integrated Research Approach

The relationship between NOVA and HEI frameworks and their application in nutritional research can be visualized as complementary pathways to dietary assessment:

The NOVA and HEI frameworks offer distinct yet complementary approaches to nutritional quality assessment. NOVA provides valuable insights into how food processing relates to health outcomes, while HEI effectively measures adherence to evidence-based dietary recommendations. Research demonstrates that these systems can be used synergistically to provide a more comprehensive understanding of dietary patterns.

For studies comparing local versus improved food varieties, employing both frameworks allows researchers to capture both processing dimensions (through NOVA) and nutritional adequacy (through HEI). This integrated approach enables a more nuanced analysis of how food systems, processing methods, and nutrient profiles interact to influence health outcomes. Future research should continue to develop standardized protocols for simultaneous application of both classification systems, particularly in understanding the nutritional implications of different food supply chains and processing methodologies.