Standardizing Nutritional Biomarker Protocols: A Framework for Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive framework for standardizing nutritional biomarker measurement, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Standardizing Nutritional Biomarker Protocols: A Framework for Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for standardizing nutritional biomarker measurement, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, from defining biomarkers and their classifications to exploring emerging multi-omics and AI technologies. The content details methodological best practices for specimen collection, storage, and analysis, alongside strategies for troubleshooting pre-analytical and biological confounders. Finally, it outlines rigorous protocols for validating biomarkers against dietary assessment tools and calibrating measurements for use in clinical research and nutritional epidemiology, aiming to enhance data reliability and cross-study comparability.

The Foundations of Nutritional Biomarkers: Definitions, Classifications, and Emerging Frontiers

Biomarker Fundamentals & Classification

What is the formal definition of a nutritional biomarker?

A nutritional biomarker is defined as a biological characteristic that can be objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or responses to nutritional interventions [1]. These biomarkers provide objective data on dietary exposure and nutritional status, circumventing the fundamental limitations and measurement errors associated with self-reported dietary assessment methods [2].

How are nutritional biomarkers classified?

Nutritional biomarkers are typically classified into three main categories based on their application and what they assess [1]:

- Biomarkers of Exposure: These assess the intake of foods, nutrients, or other dietary constituents. They can be based on traditional dietary assessment methods or, more objectively, on dietary biomarkers themselves. They are intended to account for bioavailability.

- Biomarkers of Status: These measure the concentration of a nutrient in biological fluids or tissues, or the urinary excretion of the nutrient or its metabolites. They aim to reflect total body nutrient content or the status of the tissue store most sensitive to depletion.

- Biomarkers of Function: These measure the functional consequences of a nutrient deficiency or excess. They are subdivided into:

- Functional Biochemical Biomarkers: Such as the activity of a nutrient-dependent enzyme or the presence of abnormal metabolic products.

- Functional Physiological/Behavioral Biomarkers: Such as measures of vision, growth, immune function, or cognition.

Table 1: Classification of Nutritional Biomarkers with Examples

| Category | Sub-Category | What It Assesses | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomarkers of Exposure | --- | Intake of nutrients, foods, or dietary patterns; takes bioavailability into account [1]. | Doubly labelled water for energy expenditure [2], Urinary nitrogen for protein intake [2]. |

| Biomarkers of Status | --- | Body pool size or tissue stores of a nutrient [1]. | Serum ferritin (iron stores), Plasma zinc, Plasma vitamin C [2]. |

| Biomarkers of Function | Functional Biochemical | Early functional consequences of deficiency; activity of nutrient-dependent systems [1]. | Erythrocyte glutathione reductase activity (riboflavin status), Methylmalonic acid (vitamin B12 status), Homocysteine (folate, B12, B6 status) [2] [1]. |

| Biomarkers of Function | Functional Physiological/Behavioral | Health outcomes or clinical functions impacted by nutritional status [1]. | Immune response to vaccination, Growth velocity, Cognitive function tests [1]. |

Another classification scheme, often used in validation studies, further distinguishes biomarkers as follows [2]:

- Recovery Biomarkers: Used to assess absolute intake based on metabolic balance (e.g., doubly labelled water, urinary nitrogen).

- Concentration Biomarkers: Correlated with intake but used for ranking individuals, not determining absolute intake (e.g., plasma carotenoids).

- Predictive Biomarkers: Predict intake with a dose-response relationship but have lower recovery (e.g., urinary sucrose and fructose).

Troubleshooting Common Laboratory Challenges

FAQ: Our biomarker measurements show high variability between replicates. What could be the cause?

High variability can stem from several sources related to specimen handling, assay technique, and equipment. A systematic troubleshooting approach is essential [3].

- Verify Pipette Calibration: Inaccurate pipettes are a common source of error. Ensure they are regularly calibrated and use proper pipetting technique [4].

- Check Reagent Quality and Storage: Molecular biology reagents are sensitive to improper storage. Confirm that all reagents have been stored at the correct temperature and have not expired. Visually inspect solutions for cloudiness or precipitation [3].

- Use Fresh Diluted Standards: Prepare new standard curves from fresh stock solutions to ensure accuracy [4].

- Assess Sample Homogenization: Ensure that vortex and resuspension steps are sufficient to create a homogenous sample [4].

- Repeat the Experiment: Unless cost-prohibitive, repeating the experiment can reveal if a simple mistake was made [3].

FAQ: We are getting unexpected negative results for a biomarker that should be present. How should we proceed?

- Confirm the Experiment Actually Failed: Review the scientific literature. Is there a plausible biological reason for the negative result? For instance, the biomarker might not be expressed in the specific tissue type being analyzed [3].

- Run Appropriate Controls: Always include a positive control (e.g., a sample with a known high level of the biomarker) and a negative control (e.g., a sample without the biomarker or with a control probe like bacterial dapB for RNAscope). If the positive control fails, the problem lies with the protocol or reagents, not the sample [3] [5].

- Check Equipment and Materials: Ensure reagents have been stored correctly and have not gone bad. Vendors can occasionally supply bad batches [3].

- Systematically Change Variables (One at a Time):

- Generate a list of potential culprits (e.g., fixation time, antibody concentration, number of wash steps).

- Change the easiest variable first. For example, adjust microscope settings before re-running the entire experiment [3].

- Test the most likely variable next. When testing concentrations, run a few in parallel on clearly labeled samples [3].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Common Biomarker Assay Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No Amplification (e.g., in PCR) | Poor template quality/quantity, incorrect annealing temperature (Tm), degraded reagents [4]. | Check DNA/RNA quality (e.g., Nanodrop), perform a temperature gradient PCR, increase template concentration, use fresh reagents [4]. |

| Non-Specific Amplification or Staining | Annealing temperature too low, primer concentration too high, primer self-complementarity [4]. | Increase Tm temperature, lower primer concentration, follow primer design rules to avoid repeats [4]. |

| High Background Signal | Inadequate blocking, non-specific antibody binding, over-fixation of tissue [5]. | Optimize blocking conditions, use a validated negative control probe (e.g., dapB), titrate antibody concentrations, adjust protease treatment time [5]. |

| Low Signal Intensity | Low target abundance, insufficient antibody concentration, under-fixation, too many wash steps [3]. | Increase primary/secondary antibody concentration, check target expression levels, optimize fixation time, reduce number of washes [3]. |

| Amplification in Negative Control | Contaminated reagents (especially "homemade" polymerases), non-sterile techniques [4]. | Use new reagents, opt for commercial polymerases, ensure use of sterile tips and workspace [4]. |

Standardization & Best Practices

FAQ: What are the critical factors in specimen collection and handling that can confound biomarker interpretation?

The validity of a biomarker measurement is highly dependent on pre-analytical conditions. Key factors are summarized in the table below [1].

Table 3: Key Confounding Factors in Specimen Collection and Handling

| Factor | Impact on Biomarker | Standardization Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Time of Day | Diurnal variation affects biomarkers with short half-lives (e.g., plasma zinc, iron) [2] [1]. | Collect samples from all participants at a standardized time of day [1]. |

| Fasting Status | Postprandial state can elevate fat-soluble biomarkers carried in lipoproteins [2]. | Standardize collection in a fasting state where required. |

| Specimen Type | Different specimens reflect different timeframes (serum: days; erythrocytes: months) [2]. | Pre-specify the biomarker's temporal relevance and choose specimen accordingly. |

| Storage Conditions | Repeated freeze-thaw cycles and incorrect temperature degrade biomarkers [2]. | Store in multiple aliquots at -80°C or in liquid nitrogen [2]. |

| Inflammation (Acute-Phase Response) | Inflammation can falsely alter nutrient concentrations (e.g., ferritin increases, zinc decreases) [6] [1]. | Measure CRP and AGP; apply statistical correction methods (e.g., BRINDA) [6] [1]. |

| Collection Materials | Trace elements can be contaminated by metals in tubes; some nutrients are photosensitive [2]. | Use trace-element-free tubes; protect light-sensitive nutrients (e.g., riboflavin) [2]. |

FAQ: What are the essential assay performance characteristics that should be reported for standardization?

Inconsistent reporting of laboratory methods is a significant barrier to pooling data and reproducing findings [6]. Complete disclosure is essential. The table below outlines key parameters often under-reported.

Table 4: Essential Assay Performance Characteristics for Reporting

| Assay Characteristic | Importance for Interpretation | Example of Good Reporting |

|---|---|---|

| Limit of Detection (LOD) / Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ) | Critical for interpreting low concentrations; values below LLOQ require special handling in analysis [6]. | Reporting the LOD (e.g., 0.5 mg/L for CRP) and describing how values below it were managed (e.g., imputed as LLOQ/√2) [6]. |

| Precision (Intra- & Inter-assay CV) | Indicates the reproducibility and reliability of the assay [6]. | Providing coefficient of variation (CV) percentages across the assay's reportable range [6]. |

| Assay Manufacturer & Platform | Identifies potential between-assay variation and allows for comparison [6]. | Naming the specific commercial kit, manufacturer, and product number [6]. |

| Data Handling for Unquantifiable Values | Prevents bias from excluding or improperly imputing data points outside the quantifiable range [6]. | Stating the method used (e.g., multiple imputation, substitution with a fixed value) [6]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Measures | Ensures the assay performed within expected parameters during the study [6]. | Reporting duplicate measurements and results of internal QC samples [6]. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Nutritional Biomarker Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Critical Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Kits | Quantification of specific protein biomarkers (e.g., ferritin, CRP, AGP) [6]. | Many commercial kits lack adequate validation; select and report kits from reputable manufacturers carefully [6]. |

| Doubly Labelled Water (²H₂¹⁸O) | Gold-standard recovery biomarker for measuring total energy expenditure in free-living individuals [2]. | Expensive but provides objective validation of energy intake assessment. |

| Para-Aminobenzoic Acid (PABA) | Used to check the completeness of 24-hour urine collections, which are crucial for recovery biomarkers (nitrogen, potassium) [2]. | High recovery (>85%) indicates a complete collection [2]. |

| RNAscope Probes & HybEZ System | For in-situ hybridization to detect target RNA within intact cells, a functional molecular biomarker [5]. | Requires specific conditions (Superfrost Plus slides, defined mounting media, controlled humidity/temperature) [5]. |

| PCR Master Mixes | Pre-mixed solutions for PCR, containing buffer, dNTPs, polymerase, etc., for DNA amplification [4]. | Saves time and reduces contamination risk. Requires optimization of primer concentrations and annealing temperatures [4]. |

| ImmEdge Hydrophobic Barrier Pen | Creates a barrier on slides to keep tissue sections submerged in reagent during manual assays [5]. | Critical for assays like RNAscope; not all barrier pens are compatible [5]. |

| Meta-Phosphoric Acid | Acid used as a preservative to stabilize labile biomarkers like vitamin C in samples prior to analysis [2]. | Prevents oxidation and degradation of the analyte. |

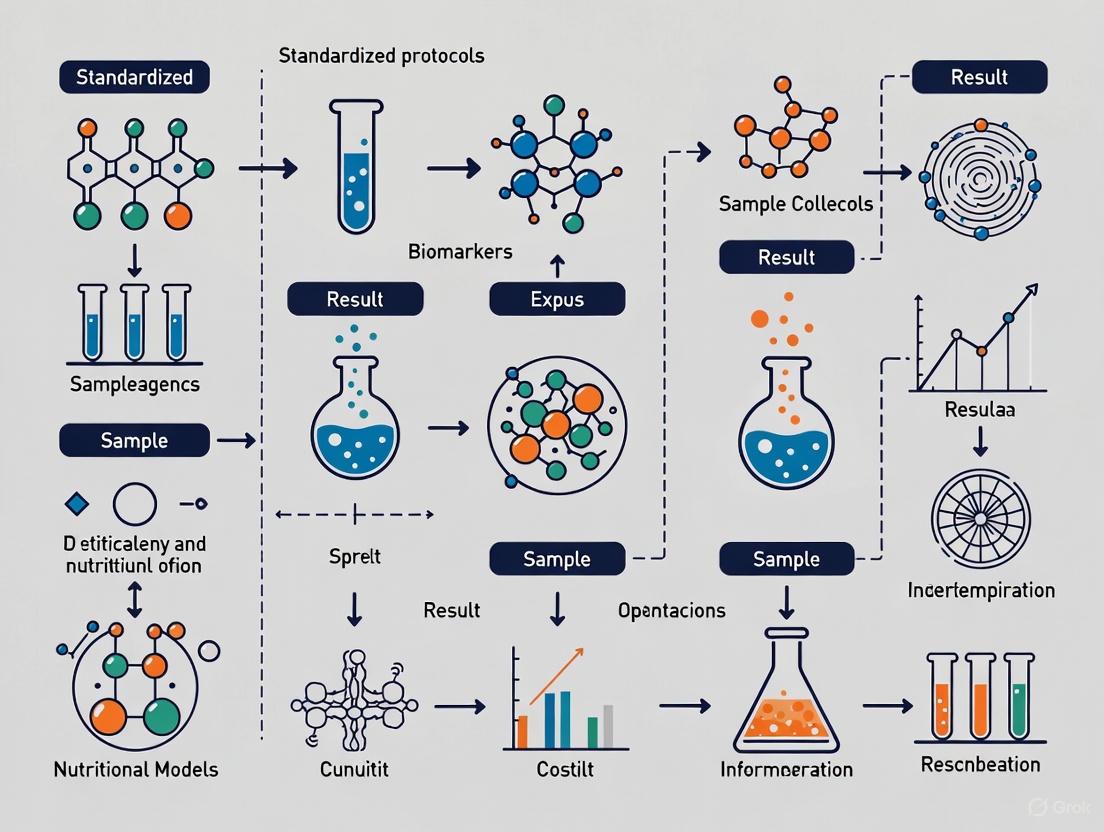

Visual Experimental Workflows

Workflow for Nutritional Biomarker Assessment

The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for developing and applying nutritional biomarkers in research, from specimen collection to data interpretation, incorporating steps to address common confounders.

Biomarker Selection and Classification Logic

This diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting the appropriate category of nutritional biomarker based on the research question and the dimension of diet or nutrition being assessed.

Core Biomarker Classifications and Definitions

Biomarkers are objectively measured and evaluated characteristics that serve as indicators of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacological responses to therapeutic intervention [7]. The table below summarizes the core classifications relevant to nutritional research.

Table 1: Core Classifications of Biomarkers in Nutritional Research

| Classification | Definition | Primary Role in Research | Example in Nutrition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recovery Biomarkers | Measures used to calibrate dietary intake measurements and correct for errors in self-reporting [8]. | To validate dietary assessment instruments and estimate actual intake [9]. | 24-hour urinary nitrogen as a biomarker for protein intake [8]. |

| Concentration Biomarkers | Reflect the concentration of a nutrient or compound in biological matrices, indicating relative intake or exposure [8]. | To assess nutritional status and exposure to specific dietary components. | Plasma alkylresorcinols for whole-grain intake; plasma carotenoids for fruit and vegetable intake [8]. |

| Predictive Biomarkers | Identify the likelihood of benefiting from a nutritional intervention or predict future health outcomes [10] [11]. | To stratify populations for targeted interventions and personalize nutrition strategies. | Genetic variants influencing nutrient metabolism; biomarker panels predicting response to a dietary intervention [12]. |

| Replacement Biomarkers | A subset of biomarkers that act as surrogate endpoints, substituting for a clinical endpoint [7] [13]. | To accelerate research by providing an interim measure of efficacy before a clinical outcome occurs. | Cholesterol levels as a surrogate for coronary artery disease risk; HbA1c as a surrogate for diabetes complications [13]. |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Validating a Recovery Biomarker (Urinary Nitrogen)

Intended Use: To validate self-reported protein intake and calibrate dietary measurement error in a cohort study [8] [9].

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Participants: Recruited cohort, fasted if required by protocol.

- Consumables: Pre-treated urine collection jugs (e.g., with boric acid as a preservative), barcoded specimen tubes [9].

- Equipment: Refrigerated storage, automated clinical chemistry analyzer.

- Reagents: Calibrators and controls for nitrogen measurement.

Detailed Procedure:

- Participant Preparation: Instruct participants on the precise 24-hour collection procedure, emphasizing the critical importance of a complete collection. The start and end times must be meticulously recorded.

- Sample Collection: Provide participants with a pre-treated collection jug. The entire 24-hour urine output must be collected and kept cool (e.g., in a refrigerator) during the collection period [9].

- Sample Processing: Upon return, the total volume of urine is measured. Multiple aliquots are created and stored at -70°C or below to ensure long-term stability of analytes [9].

- Analytical Measurement: Urinary nitrogen is typically measured using the Kjeldahl method or a validated colorimetric assay on an automated clinical chemistry analyzer. The analysis must include calibration standards and quality control (QC) pools to monitor assay performance [9].

- Data Calculation and Validation: Total urinary nitrogen (g/day) is calculated from the concentration and total urine volume. This value serves as a highly correlated biomarker for total protein intake. Data is cross-referenced with dietary questionnaires for calibration.

Protocol for Establishing a Predictive Biomarker

Intended Use: To discover and validate a biomarker panel that predicts an individual's glycemic response to a specific nutritional intervention.

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Cohorts: Well-characterized discovery and validation cohorts undergoing a controlled dietary intervention.

- Omics Platforms: Next-generation sequencing for genomics, mass spectrometry for proteomics/metabolomics [12].

- Data Analysis Tools: Bioinformatics pipelines, statistical software (R, Python), and potentially AI/machine learning algorithms [12].

Detailed Procedure:

- Discovery Phase: In a controlled feeding trial or deeply phenotyped cohort, collect baseline biological samples (e.g., blood, stool) for multi-omics analysis (e.g., genomics, metabolomics). Precisely measure the clinical outcome of interest (e.g., post-prandial glucose response) following a standardized nutritional challenge [12].

- Candidate Identification: Use univariate and multivariate statistical models to identify molecular features (e.g., specific metabolites, microbial taxa, genetic variants) that are significantly associated with the observed variation in the clinical outcome.

- Model Building: Integrate the top candidate features into a predictive algorithm using machine learning techniques. This model will output a probability or score for the expected response.

- Validation: Test the performance of the predictive algorithm in an independent cohort. The goal is to assess if the biomarker panel can accurately stratify participants as "responders" or "non-responders" to the intervention [10].

- Impact Assessment: Evaluate the population-level impact of using the biomarker for treatment selection by comparing outcomes under biomarker-guided strategy versus a one-size-fits-all approach [10].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: Our recovery biomarker data shows high intra-individual variability. How can we improve reliability? A1: High variability often stems from collection inconsistency.

- Solution: Implement rigorous participant training and use simplified collection protocols. For urinary biomarkers, consider collecting multiple non-consecutive 24-hour samples per participant to better estimate habitual excretion. Using para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) tablets as a marker of completeness can help identify and exclude incomplete collections [8] [9].

Q2: We suspect our concentration biomarker is unstable during storage. How can we verify and address this? A2: Pre-analytical handling is critical for many biomarkers.

- Solution: Refer to literature on the stability of your analyte (e.g., Vitamin C and folate are highly sensitive). During sample processing, minimize exposure to light, heat, and repeated freeze-thaw cycles. Establish stability profiles by analyzing QC materials stored under your specific conditions over time. If a systematic assay shift is detected retrospectively, use long-term QC data to statistically correct the values [9].

Q3: What are the key considerations when proposing a nutritional biomarker as a replacement (surrogate) endpoint in a clinical trial? A3: The evidence bar is high for surrogate endpoints.

- Solution: A replacement biomarker must be rigorously qualified. You must provide strong epidemiological, therapeutic, and pathophysiological evidence that changes in the biomarker consistently and accurately predict a meaningful clinical benefit (e.g., reduced disease incidence) [7]. The context of use (COU) must be clearly defined, and it is critical to remember that a biomarker validated for one intervention may not work for another [7] [13].

Q4: Our predictive biomarker panel works well in our discovery cohort but fails in the validation cohort. What could be the reason? A4: This is a common challenge in predictive biomarker development.

- Solution: This often indicates overfitting of the initial model or cohort-specific biases. Ensure your discovery cohort is sufficiently large. Use cross-validation techniques during model development. The validation cohort must be truly independent and representative of the target population. Assess if there were differences in pre-analytical protocols, assay platforms, or population characteristics that could account for the performance drop [10] [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Biomarker Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application & Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Stabilized Collection Tubes | Preserves analyte integrity from collection to processing. | EDTA tubes for plasma; PAXgene for RNA; tubes with inhibitors for labile metabolites (e.g., vitamin C). Prevents pre-analytical degradation [9]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Calibrates instruments and validates assay accuracy. | Essential for quantifying vitamins (e.g., NIST SRM for 25-hydroxyvitamin D) and minerals. Ensures results are traceable to international standards [9]. |

| Multiplex Assay Panels | Simultaneously measures multiple related biomarkers from a single sample. | Useful for profiling inflammatory cytokines, fatty acid panels, or phytoestrogen metabolites. Increases throughput and conservs precious sample [9]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Pools | Monitors assay precision and stability over time. | Prepared in-house from pooled donor samples. Run at multiple concentrations with each batch to track inter-assay variation and identify assay drift [9]. |

| DNA/RNA Extraction Kits | Isolves high-quality genetic material from various samples. | Required for genomic biomarker discovery (e.g., nutrigenetics). Must be selected based on sample type (blood, saliva, buccal cells) and downstream application (e.g., sequencing) [12]. |

| Stable Isotope Tracers | Allows precise tracking of nutrient absorption, distribution, and metabolism. | The gold-standard for studying nutrient kinetics (e.g., using 13C-labeled compounds to study fatty acid metabolism). Provides dynamic metabolic information [8]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core purpose of the BOND framework? The Biomarkers of Nutrition for Development (BOND) project is designed to provide evidence-informed advice on the selection, use, and interpretation of biomarkers of nutrient exposure, status, function, and effect. Its primary goal is to aid in generating evidence-based policy and to harmonize decision-making about which biomarkers are best suited for specific conditions and settings, thereby improving the assessment of nutritional status at both the individual and population levels [15] [16].

Q2: Why is it challenging to use serum retinol as a biomarker for vitamin A status? Serum retinol concentrations are under homeostatic control and are depressed during infection and inflammation because retinol-binding protein (RBP) is a negative acute-phase reactant. This makes it difficult to distinguish between true vitamin A deficiency and a temporary depression in concentration due to an inflammatory response [15].

Q3: What are some common laboratory-related sources of error in nutritional biomarker studies? Key sources of error include [6]:

- Specimen Handling: Inconsistencies in collection, processing, and storage (e.g., number of freeze-thaw cycles).

- Assay Performance: Lack of standardization and validation of laboratory methods and kits.

- Data Management: Inadequate handling of values below an assay's limit of detection (LOD) or lower limit of quantification (LLOQ).

- Incomplete Reporting: Failure to fully disclose assay protocols, performance characteristics, and technical limitations.

Q4: How can biomarkers be used to validate self-reported dietary intake methods? Biomarkers provide an objective measure that can circumvent the fundamental limitations of self-reported data, such as underreporting and misremembering. For example, the EPIC-Norfolk study showed a stronger inverse association between plasma vitamin C (a biomarker) and type 2 diabetes than between self-reported fruit and vegetable intake and the disease. This demonstrates how biomarkers can be used to calibrate or validate subjective dietary assessment tools [2].

Q5: What types of biological specimens are used for nutritional biomarkers, and what timeframes do they represent? Different biological specimens reflect intake over different periods [2]:

| Specimen | Timeframe of Intake Reflected |

|---|---|

| Urine | Short-term (hours to days) |

| Serum and Plasma | Short-term (days to a month) |

| Erythrocytes | Longer-term (up to 120 days) |

| Adipose Tissue | Long-term (months to years) |

| Hair and Nails | Long-term (months to years) |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Biomarker Measurements Across Studies or Laboratories

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Non-standardized assays: Use of different commercial kits or platforms with varying performance characteristics [6]. | Validate and report methods: Provide detailed information on assay manufacturers, product numbers, and protocols. Report precision estimates (intra- and inter-assay CVs) and limits of detection/quantification [6]. |

| Improper specimen handling: Degradation of analytes due to incorrect storage temperature, multiple freeze-thaw cycles, or exposure to light [2]. | Standardize SOPs: Implement detailed protocols for collection, processing, and storage. Store samples in multiple aliquots at -80°C or lower to minimize freeze-thaw cycles [2]. |

| Inflammation confounding results: Systemic inflammation can alter the concentration of nutrients like iron (ferritin) and vitamin A (retinol) [15] [6]. | Measure and adjust for inflammation: Include biomarkers of inflammation, such as C-reactive Protein (CRP) and α-1 acid glycoprotein (AGP), in the study design and apply statistical corrections [6]. |

Issue 2: Interpreting Biomarker Values Correctly

| Potential Challenge | Recommended Action |

|---|---|

| Values below the Limit of Quantification (LLOQ): A significant proportion of study samples may have unquantifiably low concentrations [6]. | Pre-specify data handling: Do not exclude these samples. Use statistically sound methods for handling them, such as substitution with LLOQ/√2 or multiple imputation, and conduct sensitivity analyses [6]. |

| Distinguishing between nutrient exposure and status: A concentration biomarker may reflect recent intake but not long-term nutritional stores [8] [2]. | Use a biomarker panel: Combine different types of biomarkers. For example, for Vitamin B12 status, measure both serum B12 (exposure/status) and methylmalonic acid (functional effect) to get a more complete picture [2]. |

| Lack of a single "gold standard" biomarker: For many nutrients, no one biomarker perfectly captures status [15]. | Use the BOND framework: Consult BOND reviews for expert advice on the best-suited biomarker for your specific research question, population, and setting. For vitamin A, multiple methods (serum retinol, RBP, isotope dilution) are related to the gold standard of liver vitamin A concentrations [15]. |

Table 1: Categories and Examples of Nutritional Biomarkers within the BOND Framework

| Category | Definition | Example Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|

| Exposure | Indicates intake of dietary constituents [8]. | Nitrogen in urine (protein intake) [8] [2]; Alkylresorcinols in plasma (whole-grain intake) [8]. |

| Status | Reflects the body's store and availability of a nutrient [2]. | Serum ferritin (iron stores); Serum retinol (vitamin A status) [15] [2]. |

| Function | Indicates a biological function that is dependent on the nutrient [8]. | Methylmalonic acid (vitamin B12 function) [2]; Erythrocyte glutathione reductase activity (riboflavin status) [2]. |

| Effect | Reflects a health outcome or disease state influenced by nutrition. | Hemoglobin concentration (anemia); Xerophthalmia (vitamin A deficiency) [15]. |

Table 2: Biomarker Laboratory Assay Reporting Standards Based on a review of 20 articles, key assay characteristics are often under-reported [6]:

| Laboratory Assay Characteristic | Percentage of Publications Reporting it |

|---|---|

| Specific Analyzer and/or Assay Manufacturer | 80% |

| Inter-assay and/or Intra-assay Coefficient of Variation (CV) | 35% |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) and/or Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ) | 20% |

| Duplicate Measurements Performed for Each Sample | 10% |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Vitamin A Status Using the BOND Framework

Background: No single biomarker provides a perfect assessment of vitamin A status. The BOND review recommends a context-specific approach [15].

Methodology:

- Specimen Collection: Collect non-fasting blood sample via venipuncture. Protect from light. Process to obtain serum or plasma and store at -80°C in aliquots [15] [2].

- Primary Biomarker of Status/Exposure:

- Functional Biomarker:

- Analyte: Breast-milk retinol (in lactating women) is a functional indicator of vitamin A status in both mother and infant [15].

- Advanced/Reference Methods:

- Dose-response tests: Measure the rise in serum retinol after a physiological dose of vitamin A.

- Isotope dilution: Considered a more robust measure of total body stores [15].

Protocol 2: Validating a Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) Using a Recovery Biomarker

Background: Self-reported dietary data is prone to error. Recovery biomarkers, like doubly labeled water for energy intake, provide an objective measure to validate these instruments [2].

Methodology (Using 24-hour Urinary Nitrogen as a Recovery Biomarker for Protein Intake):

- Participant Preparation: Instruct participants to collect all urine for a strict 24-hour period.

- Compliance Monitoring: Administer para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) tablets to assess completeness of collection. A recovery of >85% indicates a complete sample [2].

- Specimen Handling: Pool the total 24-hour urine volume, aliquot, and store frozen.

- Laboratory Analysis: Analyze urinary nitrogen concentration using the Kjeldahl method or chemiluminescence.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate total urinary nitrogen (TUN) excretion over 24 hours.

- Calculate protein intake using the formula: Protein (g/day) = (TUN (g/day) + 2) * 6.25, where the constant 2 accounts for non-urinary nitrogen losses.

- Compare this biomarker-derived protein intake estimate with the intake reported from the FFQ to assess the validity and calibration of the FFQ [2].

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

BOND Biomarker Cascade

Biomarker Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Nutritional Biomarker Studies

| Item | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Serum/Plasma Tubes | Collection of blood for analysis of most vitamins (e.g., A, B12), minerals, and inflammatory markers. | Use trace-element-free tubes for mineral analysis. Specify anticoagulant for plasma (e.g., EDTA, Heparin) [2]. |

| Urine Collection Jugs | 24-hour urine collection for recovery biomarkers (Nitrogen, Potassium, Sodium). | Use opaque, pre-acidified jugs for analytes sensitive to degradation. Include PABA tablets to monitor compliance [2]. |

| Cryogenic Vials | Long-term storage of biological specimens at ultra-low temperatures. | Use O-ring seals to prevent freezer burn. Store in multiple aliquots to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles [6] [2]. |

| ELISA Kits | Immunoassay for quantifying proteins (e.g., Ferritin, RBP, CRP, AGP). | Select kits that have been independently validated. Report manufacturer, product number, and performance characteristics (CV, LLOQ) [6]. |

| HPLC Columns & Standards | Separation and quantification of specific molecules (e.g., retinol, carotenoids, tocopherols). | Required for precise measurement of many micronutrients. Use internal standards to correct for recovery [15]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Pools | Monitor assay precision and accuracy across multiple analytical runs. | Include high, medium, and low concentration QC samples in each batch to detect assay drift [6]. |

| Stabilizing Additives | Prevent degradation of labile analytes during processing and storage. | Example: Meta-phosphoric acid to stabilize vitamin C in plasma [2]. |

FAQs: Navigating Multi-Omics and AI Integration

1. What are the primary data integration challenges in multi-omics studies, and how can AI address them? A major challenge is the horizontal integration of unmatched data from different cells or the vertical integration of multiple data types from the same sample [17]. AI frameworks, such as the dual-path graph attention auto-encoder (SSGATE), are being developed to effectively integrate single-cell and spatial multi-omics data, helping to reconcile these different data structures [17].

2. How can I prevent overfitting when training AI models on high-dimensional multi-omics data? Overfitting occurs when a model is too complex for the amount of data. To mitigate this, ensure your experimental design has sufficient biological replicates [18]. During analysis, employ variable selection methods like shrinkage and control for multiple comparisons using measures such as the false discovery rate (FDR) [19]. Using a panel of continuous biomarkers, rather than a single dichotomized one, can also help retain maximal information and improve model generalizability [19].

3. Our discovered biomarkers lack clinical utility. How can we better align discovery with application? A clearly defined Context of Use (COU) is critical from the outset. The COU specifies the biomarker's category and its intended decision-making purpose [20]. The study design, statistical analysis plan, and acceptable levels of measurement error are all dependent on this context. Studies that only show group differences, without demonstrating utility for individual-level decision-making, are insufficient for validation [20].

4. What are the key considerations for analytical validation of a biomarker assay? Analytical validation establishes the technical performance of the assay itself. It requires evaluating performance characteristics such as sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and precision according to a specified technical protocol [20]. Key parameters to report include the lower limit of detection (LOD), lower limit of quantification (LLOQ), and intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation (CV) [6].

5. Why is data standardization and sharing so important in this field? Adopting FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) data principles is fundamental for scientific progress [21]. Standardized data allows for validation of results, facilitates the pooling of datasets for larger meta-analyses, and provides the vast, high-quality datasets needed to train robust AI models, as exemplified by the development of AlphaFold [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent or Irreproducible Biomarker Measurements

Problem: Biomarker measurements vary significantly between batches, labs, or sample collection events.

Solution:

- Standardize Pre-Analytical Protocols: Implement and document detailed, standardized procedures for specimen collection, handling, and storage. For nutritional biomarkers, this is critical due to analyte instability [6] [18].

- Implement Rigorous Analytical Validation: Before clinical validation, thoroughly assess your assay's precision, sensitivity, specificity, LOD, and LLOQ [20]. Use technical replicates to calculate intra- and inter-assay CVs.

- Control for Biological Confounders: Account for factors known to affect nutritional biomarkers, such as inflammation (e.g., by measuring C-reactive protein), age, and sex, in your experimental design and statistical analysis [6] [22].

- Apply Randomization and Blinding: Randomly assign cases and controls to testing plates or batches to control for technical "batch effects." Blind laboratory personnel to clinical outcomes to prevent assessment bias [19].

Issue 2: Poor Performance of AI/ML Models in Clinical Validation

Problem: A biomarker signature that performed well in the discovery cohort fails to generalize to an independent patient population.

Solution:

- Define Context of Use Early: Ensure your discovery phase is tailored to a specific COU (e.g., prognostic vs. predictive). A predictive biomarker, for instance, must be identified through a test of interaction with a treatment in a randomized trial [19].

- Avoid Overfitting with Proper Study Design: Power your study with an adequate number of samples and clinical events. Use data from prospective trials or well-curated sample banks where possible [19] [18].

- Utilize Advanced Visualization Tools: Employ tools like 3D IntelliGenes to create configurable 3D scatter plots. This helps visualize disease state distributions, classifier bias, and patient similarity, allowing you to identify outliers and assess model generalizability before clinical validation [23].

- Ensure Rich Metadata: Capture comprehensive metadata at every experimental step. This provides the necessary context for AI models and other researchers to correctly interpret and reuse the data, minimizing the risk of false assumptions [21].

Issue 3: Ineffective Visualization and Interpretation of Multi-Dimensional Data

Problem: It is difficult to visualize and communicate the complex relationships within multi-omics datasets.

Solution:

- Adopt Multi-Dimensional Visualization: Move beyond traditional 2D plots. Use platforms that offer 3D visualization to capture both linear and non-linear structures in the data, which can reveal patient clusters and model errors that would otherwise be missed [23].

- Prioritize Accessibility in Charts: When creating charts, ensure sufficient color contrast. A creative solution is to use elements like high-contrast end caps on graph bars, which allows the use of a broader, more visually distinct palette while remaining accessible to colorblind and low-vision users [24].

- Perform Joint Feature Analysis: Use feature plotting modules to analyze the interdependence and discriminative power of pairs of multi-omics features, such as co-expressed biomarkers [23].

Essential Data Analysis Metrics

When evaluating biomarker performance, the choice of metric depends on the intended use. The table below summarizes key statistical measures.

Table 1: Key Statistical Metrics for Biomarker Evaluation [19]

| Metric | Description | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Proportion of true cases correctly identified. | Diagnostic and screening biomarkers. |

| Specificity | Proportion of true controls correctly identified. | Diagnostic and screening biomarkers. |

| Positive Predictive Value (PPV) | Proportion of test-positive individuals who have the disease. | Informs clinical utility; depends on prevalence. |

| Negative Predictive Value (NPV) | Proportion of test-negative individuals who do not have the disease. | Informs clinical utility; depends on prevalence. |

| Area Under the Curve (AUC) | Overall measure of how well the biomarker distinguishes cases from controls. | General assessment of diagnostic/prognostic accuracy. |

| Calibration | How well the biomarker's predicted risks match observed risks. | Critical for risk stratification biomarkers. |

| Hazard Ratio (HR) | Measure of the magnitude and direction of the effect on a time-to-event outcome. | Primary metric for prognostic biomarkers. |

Experimental Workflow for Multi-Omics Biomarker Discovery

The following diagram outlines a robust workflow from experimental design to clinical application, incorporating steps to address common pitfalls.

Data Preprocessing for AI-Ready Datasets

A crucial step before AI model training is the preprocessing of raw multi-omics data. This workflow ensures data quality and interoperability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Resources for Multi-Omics Biomarker Research

| Item / Resource | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometry | High-throughput identification and quantification of proteins (proteomics) and metabolites (metabolomics) [17] [18]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Profiling genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic data. Single-cell NGS allows resolution at the individual cell level [19] [17]. |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Capturing gene expression data while preserving the spatial location of cells within a tissue section [17]. |

| Antibody-based Assays (e.g., ELISA) | Targeted measurement of specific protein biomarkers. Requires careful validation to ensure specificity [6]. |

| 3D IntelliGenes Software | An AI/ML application for creating interactive 3D visualizations of multi-omics data to assess disease states and model performance [23]. |

| FAIR Data Management Plan | A framework to ensure data is Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable, which is crucial for collaboration and AI training [21]. |

| Relational Database | A data management system to logically link rich metadata from multi-step, multi-omics experiments, ensuring traceability and context [21]. |

The Critical Role of Standardization in Precision Nutrition and Clinical Trials

FAQs: Core Concepts and Common Challenges

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between precision nutrition and traditional dietary advice?

Precision nutrition is an approach that uses individual data—including genetics, microbiome, metabolic profile, and lifestyle—to predict a person's response to specific foods and deliver tailored dietary recommendations [25] [26]. Unlike traditional "one-size-fits-all" dietary guidelines, it recognizes that healthful eating varies between individuals and changes over time [25]. It leverages high-throughput omics technologies (genomics, metabolomics, proteomics) and data analytics to develop dynamic, personalized interventions [27] [26].

Q2: Why is standardization so critical in precision nutrition research?

Standardization is essential because a lack of consensus on protocols and reference values hinders the clinical translation of biomarkers [28]. Without standardized measurement techniques, results from different studies cannot be reliably compared or validated, which limits the development of actionable clinical guidelines and creates reproducibility challenges [28] [27]. Standardized metrics enhance oversight and decision-making in clinical trials, though they must sometimes be supplemented with study-specific indicators to capture unique risks [29].

Q3: What are the main biomarkers used in precision nutrition, and what standardization challenges do they face?

The table below summarizes key biomarkers and associated standardization challenges.

Table 1: Key Biomarkers in Precision Nutrition and Standardization Challenges

| Biomarker | What It Measures | Primary Standardization Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Epigenetic Clocks [28] | Biological age based on DNA methylation patterns | Lack of clinical validation; no consensus on standardized protocols or reference values [28]. |

| Telomere Length [28] | Cellular aging and chronic disease risk | Variability in measurement techniques; lack of standardized reference values [28]. |

| Metabolomic Profiles [30] [26] | Real-time metabolic shifts and responses to diet | Methodological inconsistencies in profiling and data analysis; integrating multi-omics data [27] [26]. |

| Gut Microbiome [25] [26] | Microbial diversity and function via metagenomics | Variability in sequencing and analysis methods; high inter-individual diversity [26]. |

Q4: My omics data shows statistically significant associations, but how do I determine if they are clinically relevant?

This is a common challenge in translational research. Statistically significant associations alone are insufficient for clinical application [25]. To assess clinical relevance, you must evaluate the effect size and predictive power of the findings. Research should demonstrate that the biomarker or signature can accurately predict a meaningful health outcome or response to a dietary intervention in a controlled setting [25]. Furthermore, the underlying algorithms must have robust validation and clinical relevance before being incorporated into products or services [25].

Troubleshooting Guides: Experimental Issues and Solutions

Issue 1: Inconsistent Biomarker Measurements Across Labs

Problem: Measurements of the same biomarker (e.g., telomere length) yield inconsistent results when protocols differ between laboratories [28].

Solution:

- Adopt a Standardized Protocol: If available, use a consensus protocol from your field. Current guidelines recommend combining biomarkers like telomere length and epigenetic age with other molecular data within integrative assessment approaches [28].

- Use Common Reference Materials: Implement internal controls and reference standards across all runs and sites to calibrate measurements.

- Cross-Validate Techniques: Periodically compare results from your lab's method with a gold-standard reference method, if one exists.

Issue 2: High Variability in Postprandial Response Data

Problem: Significant inter-individual variability in metabolic responses to the same meal makes it difficult to identify consistent patterns or draw general conclusions.

Solution:

- Deep Phenotyping: Collect comprehensive data on participants (genetics, baseline metabolism, microbiome) to stratify responses into distinct metabotypes [26].

- Standardize Test Conditions: Control for variables that significantly impact metabolic response, such as:

- Time of day and circadian rhythm [26]

- Prior physical activity and fasting status

- Exact composition and format of the test meal

- Leverage Multi-omics Integration: Use integrated omics approaches to move beyond single biomarkers and understand the complex network of interactions contributing to the observed variability [27] [31].

Issue 3: Translating Omics Findings into Clinically Actionable Advice

Problem: Research identifies promising genetic or metabolomic signatures, but translating them into practical, effective, and safe dietary recommendations for individuals remains difficult [27].

Solution:

- Validate in Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs): Design RCTs to test whether interventions based on the specific signature lead to improved health outcomes compared to standard care [26].

- Follow Reporting Guidelines: Adhere to updated consensus guidelines like CONSORT 2025 for reporting trials and SPIRIT for trial protocols to ensure transparency and reproducibility [32] [33].

- Assess Real-World Usability: Evaluate whether the resulting intervention is feasible, understandable, and actionable for the target audience, considering their food environment and socioeconomic status [25] [26].

Standardized Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Implementing a Precision Nutrition Randomized Controlled Trial

This protocol is structured according to the updated SPIRIT 2013 framework, which defines standard items for clinical trial protocols [32].

Table 2: Key Protocol Elements for a Precision Nutrition RCT

| Protocol Item | Description and Application |

|---|---|

| Trial Design | Specify type (e.g., parallel, factorial), allocation ratio, and framework (e.g., superiority). Clearly state the randomization method [34]. |

| Eligibility Criteria | Define criteria for participants and, critically, for sites and individuals delivering the intervention to ensure consistency [33]. |

| Interventions | Describe each intervention with sufficient detail to allow replication, including the method of personalization (e.g., algorithm, biomarker cutoff) [34] [33]. |

| Outcomes | Define primary and secondary outcomes clearly. For precision nutrition, these may include biomarker changes, clinical endpoints, and patient-reported outcomes [34]. Use the SPIRIT-Outcomes extension for guidance [32]. |

| Statistical Methods | Make the statistical analysis plan accessible prior to trial commencement. Specify how inter-individual variability will be modeled and define who is included in each analysis [33]. |

| Harms | Plan for the assessment and reporting of potential harms or adverse events related to the personalized dietary advice [33]. |

| Data Sharing | Include a plan for sharing de-identified participant data, as this is a new item in modern guidelines like CONSORT 2025 [33]. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram: From Standardization Gaps to Research Impacts

Diagram: Multi-Omics Integration Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Kits for Precision Nutrition

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation Kits [28] | Quantify epigenetic age using epigenetic clocks. | Select kits that target established, published CpG sites; ensure batch-to-batch consistency. |

| Telomere Length Assay Kits [28] | Measure telomere length as a biomarker of cellular aging. | Prefer high-throughput qPCR methods; use internal controls to normalize results across runs. |

| Metabolomic Profiling Panels [30] [26] | Identify and quantify small molecule metabolites in bio-fluids. | Choose targeted panels for specific pathways or untargeted for discovery; standardize sample preparation. |

| Metagenomic Sequencing Kits [25] [26] | Characterize the gut microbiome composition and function. | Use shotgun sequencing for functional insight; standardize DNA extraction and bioinformatics pipelines. |

| Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGM) [25] | Monitor real-time interstitial glucose levels. | A wearable device, not a reagent; crucial for validating personalized metabolic responses. |

Methodological Best Practices: From Specimen Collection to Analysis

Specimen Selection Guide and Biomarker Applications

The selection of an appropriate biological specimen is fundamental to the accuracy and reliability of nutritional biomarker measurement. Different specimens offer unique windows into nutritional status, reflecting varying aspects of exposure, metabolism, and long-term storage.

Table: Comparison of Biological Specimens for Nutritional Biomarker Analysis

| Specimen Type | Key Biomarkers | Strengths | Limitations | Reflective Timeframe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma/Serum | Carotenoids, Vitamins (A, E), Isoflavones, Fatty Acids, Holotranscobalamin (B12) | Captures recent dietary intake and current metabolic status [35]. | Concentrations can be transient, influenced by recent meals and lipid transport [35] [36]. | Short-term (hours to days) |

| Urine | Isoflavones, Enterolactone, 1-Methylhistidine (meat intake marker) [35] | Non-invasive collection; good for measuring excretion of water-soluble biomarkers and metabolites [35] [37]. | Requires normalization (e.g., to creatinine); concentration varies with hydration. | Short-term (hours) |

| Erythrocytes (RBC) | α-Tocopherol (Vitamin E), Fatty Acids [36] | Longer lifespan (~120 days) provides a medium-term indicator of status, less fluctuation than plasma [36]. | More complex processing required to isolate packed cells [36]. | Medium-term (weeks to months) |

| Adipose Tissue | α-Tocopherol (Vitamin E), Fatty Acids [35] [36] | Represents the primary long-term storage depot for lipid-soluble nutrients; excellent for assessing chronic status [36]. | Invasive biopsy procedure required; not suitable for high-frequency monitoring [36]. | Long-term (months to years) |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our plasma vitamin E (α-tocopherol) measurements are highly variable between participants. How can we improve the reliability of our status assessment?

A1: Consider complementing plasma analysis with measurements in erythrocytes or adipose tissue. Plasma α-tocopherol is highly dependent on blood lipid concentrations and reflects recent intake. In contrast, erythrocyte α-tocopherol provides a more stable, medium-term measure of status, while adipose tissue α-tocopherol is considered the gold standard for assessing long-term body stores [36]. This multi-specimen approach is particularly crucial for monitoring patients with lipid malabsorption disorders [36].

Q2: We need to validate self-reported vegetarian diet patterns in our cohort. Which biomarkers and specimens are most informative?

A2: A panel of biomarkers across different specimens provides objective validation.

- Plasma: Significantly higher total carotenoids and linoleic acid, and lower saturated fatty acids (e.g., myristic, palmitic) in vegans [35].

- Urine: Markedly higher excretion of isoflavones (from soy/legumes) and enterolactone (a lignin metabolite) in vegetarians [35].

- Urine: 1-Methylhistidine is a highly specific marker for meat intake; levels were 92% lower in vegans compared to non-vegetarians [35].

Q3: What are the critical pre-analytical steps to ensure the integrity of biospecimens for NMR-based metabolomics?

A3: Standardized protocols are essential for reproducible data [38] [37].

- Collection: Use pre-prepared kits with appropriate, non-interfering collection tubes (e.g., correct anticoagulants) [38].

- Processing: Process samples promptly (e.g., within 4 hours for blood to separate plasma/erythrocytes) [36] [37]. Prepare aliquots immediately to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles, which can degrade proteins and other labile molecules [38].

- Storage: Store specimens at the coldest feasible temperature (e.g., -80°C or in liquid nitrogen vapor below -150°C) to maximize stability [38].

Troubleshooting Common specimen Handling Issues

Table: Common Specimen Handling Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Corrective & Preventive Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Hemolyzed blood sample | Difficult venipuncture, rough handling during or after collection [38]. | Use proper venipuncture technique; gentle inversion of tubes; avoid forceful pipetting. Note hemolysis and consider rejecting sample for certain analytes (e.g., NSE) [38]. |

| Degradation of labile biomarkers | Delayed processing; inappropriate storage temperature; multiple freeze-thaw cycles [38]. | Minimize time from collection to processing and freezing. Create multiple single-use aliquots during initial processing to avoid repeated thawing [38]. |

| Inconsistent NMR spectroscopic results | Analytical bias from slight variations in sample prep (pH, temperature) or instrument drift [37]. | Follow a strict, standardized sample preparation protocol. Use a buffer solution. Include internal standards and run quality control (QC) samples periodically throughout the analysis batch [37]. |

| Insufficient sample volume for replication | Inadequate aliquot planning; unforeseen need for additional assays. | Develop a data sharing and aliquot management plan early in the study. Prioritize the use of archived specimens and consider utilizing centralized biorepositories for efficient storage and distribution [39]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This protocol is essential for accurately assessing vitamin E status across different biological compartments.

I. Sample Collection and Pre-processing

- Plasma & RBC: Collect blood in lithium heparin tubes. Process within 4 hours. Centrifuge to separate plasma. Wash red blood cells three times in saline solution with pyrogen (10 g/L). Resuspend to a hematocrit of 50% as "packed cells" [36].

- Adipose Tissue: Obtain ~50-100 mg of subcutaneous adipose tissue via needle biopsy during surgery. Immediately wash with saline, freeze in liquid nitrogen, and store at ≤ -70°C [36].

II. HPLC Analysis for α-Tocopherol

- Extraction: For all matrices, proteins are precipitated with ethanol, and α-tocopherol is extracted into hexane. The hexane layer is evaporated under nitrogen, and the residue is dissolved in methanol/ethanol [36].

- Chromatography:

- System: High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) with UV detection (292 nm).

- Column: Adsorbosphere HS C18 3μm.

- Mobile Phase: Gradient elution starting with methanol-acetonitrile (40/60, v/v) and ending with methanol-acetonitrile-dichloromethane (46/30/24, v/v).

- Internal Standard: Use Tocol to correct for extraction losses [36].

- Quality Control: Assay two levels of internal quality control samples at the start of each run. Participate in external quality-assurance programs [36].

This protocol is used for high-throughput screening and biomarker discovery in nutritional studies.

I. Sample Preparation

- Urine: Centrifuge to remove solid debris. Mix a standardized volume of urine with a phosphate buffer (e.g., 0.2 M Na₂HPO₄, pH 7.4) to minimize pH variation across samples. A known amount of an internal chemical shift standard (e.g., TSP, sodium 3-trimethylsilylpropionate) is added [37].

- Plasma/Serum: Use ~200-300 μL of sample. For lipoprotein profiling, add D₂O for a field-frequency lock [37].

II. NMR Spectroscopy Acquisition

- Standard 1D 'H NMR: Uses a simple pulse-acquisition sequence with water signal suppression. This is the primary method for generating metabolic profiles.

- Relaxation-Edited (CPMG) Sequences: Uses spin-echo pulses to filter out signals from broad macromolecules (proteins, lipoproteins), enhancing the detection of low-molecular-weight metabolites.

- Diffusion-Edited (LED) Sequences: Uses pulsed magnetic field gradients to attenuate signals from small molecules, selectively highlighting signals from macromolecules like lipids and proteins.

- 2D J-Resolved (JRES) Spectroscopy: Spreads the signals in two dimensions, separating chemical shift from spin-spin coupling constants. This simplifies crowded spectra and aids in metabolite identification [37].

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Biomarker Research Workflow

Nutrition & Metabolic Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials and Reagents for Nutritional Biomarker Research

| Item | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Lithium Heparin Tubes | Blood collection for plasma and RBC separation [36]. | Prevents coagulation; suitable for a wide range of molecular analyses. Check for potential interference with specific assays [38]. |

| Cryogenic Vials | Long-term storage of biospecimens (plasma, RBC, tissue homogenates) [38]. | Use threaded caps for secure sealing at ultra-low temperatures. Select material (e.g., polypropylene) that does not leach compounds and is stable at ≤ -70°C [38]. |

| Tocol | Internal Standard for HPLC analysis of α-tocopherol [36]. | Added at the beginning of extraction to correct for procedural losses, improving analytical accuracy and precision [36]. |

| Deuterated Solvent (D₂O) | Solvent for NMR spectroscopy [37]. | Provides a field-frequency lock for the NMR spectrometer. Required for stable data acquisition [37]. |

| Chemical Shift Standard (e.g., TSP) | Internal reference for NMR spectroscopy [37]. | Used to calibrate the chemical shift axis (δ scale) to 0 ppm, ensuring consistency and comparability of spectra between samples and instruments [37]. |

| Pyrogallol Solution | Preservative for erythrocyte samples [36]. | Added to the saline wash solution to prevent oxidation of labile compounds like vitamin E during RBC processing [36]. |

Pre-analytical variables represent the most significant source of error in nutritional biomarker research, accounting for up to 75% of all laboratory errors [40]. This technical support center provides targeted guidance for standardizing three critical pre-analytical variables—timing, fasting status, and seasonality—within nutritional biomarker measurement protocols. Proper control of these factors is essential for maintaining metabolic integrity and ensuring that analytical profiles accurately reflect the in vivo biochemical status rather than technical artifacts [41].

Reference Tables for Pre-Analytical Variables

Table 1: Impact of Timing and Fasting Status on Specific Biomarkers

| Biomarker Category | Specific Analytes | Fasting Requirement | Circadian Variation | Postprandial Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Metabolism | Glucose, Triglycerides | Required (10-14 hours) | Significant diurnal patterns | Increases significantly after meals [40] |

| Cardiac Biomarkers | Cardiac Troponins (cTnI, cTnT) | Not required for most assays | Diurnal rhythm with morning peaks [42] | Minimal direct effect [42] |

| Vitamin Status | Fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) | Recommended | Not well characterized | Lipoprotein changes may affect measurements [2] |

| Nutritional Biomarkers | Plasma Vitamin C, Carotenoids | Required for accurate assessment | Not well documented | Affected by recent fruit/vegetable intake [8] [2] |

| Natriuretic Peptides | BNP, NT-proBNP | Not routinely required | Limited data available | Minimal direct food interference [42] |

Table 2: Seasonal Considerations for Nutritional Biomarkers

| Biomarker | Seasonal Variation | Magnitude/Pattern | Primary Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin D (25-OH-D) | Pronounced variation | Higher in summer months [2] | Sun exposure differences affecting cutaneous synthesis |

| Lycopene | Moderate variation | Varies with harvest seasons [2] | Tomato availability and consumption patterns |

| Other Carotenoids | Possible variation | Depends on food availability | Seasonal changes in fruit/vegetable consumption |

| Inflammatory Markers | Limited data | Inconsistent findings | Potential weather-related activity changes |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Timing and Circadian Variations

Q: Which nutritional biomarkers exhibit significant circadian variation that must be controlled in research protocols?

A: Circadian rhythms significantly affect several key biomarkers:

- Serum iron can increase by up to 50% from morning to afternoon [40]

- Serum potassium may decline by an average of 1.1 mmol/L from morning to afternoon [40]

- Cardiac troponin T (measured with high-sensitivity assays) demonstrates diurnal rhythm with peak concentrations during morning hours, gradually decreasing throughout daytime [42]

- Hormonal markers including cortisol, renin, aldosterone, and corticotropin show pronounced circadian patterns [40]

Protocol Recommendation: Collect all samples within the same time window (ideally early morning) across the entire study to minimize circadian variability [41]. Document actual collection times meticulously.

Fasting Status Control

Q: What is the optimal fasting duration for nutritional biomarker studies, and how should we manage non-fasting samples?

A: The evidence supports:

- Standard fasting period: 10-14 hours overnight fasting prior to blood collection [40]

- Critical biomarkers requiring fasting: Glucose, triglycerides, and most nutritional biomarkers (e.g., plasma vitamin C, carotenoids) [2] [40]

- Lipemia impact: Inadequate fasting is the most common pre-analytical cause of lipemia, which can interfere with various laboratory methods [42]

Troubleshooting non-fasting samples:

- Document fasting duration accurately for all participants

- For accidentally non-fasted samples, consider using ultracentrifugation or high-speed centrifugation (for cardiac troponins) [42]

- Note that some fat-soluble markers (e.g., carotenoids) in postprandial samples may be partly present in lipoprotein cholesterol, requiring careful interpretation [2]

Seasonal Variation Management

Q: How significant is seasonal variation in nutritional biomarkers, and what strategies can minimize its impact on study validity?

A: Seasonal effects are well-documented for specific biomarkers:

Vitamin D Protocol:

- Consider stratified sampling across seasons for study populations

- For single-timepoint studies, record season of collection as a potential covariate

- In longitudinal studies, collect samples during the same season for each participant at follow-up timepoints

Food-based Biomarker Protocol:

- For biomarkers reflecting specific food intake (e.g., lycopene from tomatoes), document seasonal availability of key foods in food frequency questionnaires

- Consider batch analysis by season to account for potential assay variation

Experimental Protocol for Pre-Analytical Standardization

Sample Collection Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pre-Analytical Standardization

| Item | Specification | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Collection Tubes | Consistent manufacturer and type throughout study | Minimize tube-derived contaminants (polymers, plasticizers, slip agents) [41] | Gel separator tubes not recommended for metabolomics; document anticoagulant type |

| Para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) | >85% recovery threshold | Assess completeness of 24-hour urine collections [2] | Critical for recovery biomarkers (nitrogen, potassium, sodium) |

| Meta-phosphoric acid | Specific concentration for stabilization | Preserve unstable biomarkers (e.g., vitamin C) during storage [2] | Prevents oxidation of acid-sensitive biomarkers |

| LipoClear or equivalent | Laboratory-grade lipid clearing reagent | Remove lipemia interference from samples [42] | Not suitable for all assays (e.g., cardiac troponins) - verify compatibility |

| Cryogenic Storage Tubes | Pre-labeled, trace-metal free | Proper aliquot storage at -80°C [2] [41] | Prevents repeated freeze-thaw cycles; maintains sample integrity |

| DLW Protocol Materials | Deuterium and oxygen-18 labeled H₂O | Objective energy intake assessment [43] | Considered gold standard for total energy expenditure measurement |

Quality Control & Monitoring Framework

Implement these quality indicators to monitor pre-analytical performance:

- Sample Collection Timing Compliance: Percentage of samples collected within specified time window (target: >95%)

- Fasting Protocol Adherence: Documentation of fasting duration for all participants (target: 100%)

- Seasonal Distribution Balance: Even distribution of sample collection across seasons or appropriate stratification

- Hemolysis Index Tracking: Percentage of samples exceeding acceptable hemolysis thresholds (target: <3%)

- Sample Processing Timeliness: Time from collection to freezing (target: <2 hours for most biomarkers)

Documentation Requirements:

- Actual vs. scheduled collection time differences

- Fasting duration verification

- Participant posture during phlebotomy

- Seasonal timepoint with date of collection

- Any protocol deviations or exceptional circumstances

By implementing these standardized protocols and troubleshooting guides, researchers can significantly reduce pre-analytical variability and enhance the reliability of nutritional biomarker data for drug development and clinical research applications.

Protocols for Sample Processing, Storage, and Avoiding Degradation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical factors to prevent RNA degradation during storage? RNA is highly susceptible to degradation by RNases, which are ubiquitous and stable enzymes. The key to prevention involves multiple strategies: using RNase-free reagents and consumables, working in a dedicated clean workspace, and adding RNA stabilization reagents. For long-term integrity, flash-freezing samples in liquid nitrogen immediately after collection and storing them at -70°C or lower in small aliquots is essential to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles [44].

Q2: How do sample storage protocols impact the reproducibility of nutritional biomarker research? Inconsistent sample handling and storage are significant sources of variability, which can hinder data pooling and meta-analyses. For example, the BRINDA project identified wide variability in blood collection procedures and sample storage methods as a major barrier to combining data from different nutritional surveys. Detailed, standardized protocols for specimen storage are crucial for ensuring the validity and reproducibility of biomarker data [6].

Q3: What is the "fit-for-purpose" approach in biomarker assay validation? The "fit-for-purpose" approach means that the level of analytical validation for a biomarker assay should be tailored to its specific context of use (COU) in the drug development process. Unlike drug bioanalysis, fixed validation criteria are not always appropriate. The assay's performance characteristics, such as accuracy and precision, are developed based on the specific objectives of the biomarker measurement and the subsequent clinical interpretations [45] [13].

Q4: Why is the choice of storage container important, and what should be considered? The container material can directly affect sample integrity. Glass may crack under extreme temperatures, while certain plastics can absorb analytes or leach contaminants. The container size should match the sample volume to minimize headspace, which can degrade sample quality. Labels must be permanent, waterproof, and use a standardized format for consistent identification [46].

Troubleshooting Common Sample Degradation Issues

Table 1: Common Issues and Corrective Actions in Sample Handling

| Problem | Potential Cause | Corrective & Preventive Actions |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Degradation [44] | RNase contamination; improper storage temperature; repeated freeze-thaw cycles. | Use RNase-deactivating reagents on surfaces; employ single-use, certified RNase-free plasticware; store purified RNA in aliquots at -70°C; always keep samples on ice during processing. |

| Poor Assay Reproducibility [6] [13] | Inconsistent handling or storage across samples; unvalidated assay methods; lack of documented protocols. | Establish and adhere to Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for all processing and storage steps; perform analytical method validation based on the context of use; document all protocols in detail. |

| Loss of Biomarker Activity [46] | Exposure to inappropriate temperature, light, or moisture; reactive container materials. | Optimize storage conditions (e.g., -80°C for most biologicals); use opaque or amber containers for light-sensitive samples; ensure containers are chemically inert and tightly sealed. |

| Variable Biomarker Data [47] | Failure to follow sample stabilization requirements; improper pre-processing delays. | Implement immediate sample stabilization after collection (e.g., flash-freezing, chemical stabilizers); minimize the time between collection and stabilization/freezing. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Objective: To create a dedicated workspace and adopt practices that minimize RNase contamination for high-quality RNA isolation.

Materials:

- RNase-deactivating reagents (e.g., commercial disinfectants, RNAZap)

- Disposable gloves

- RNase-free pipette tips, microcentrifuge tubes, and plasticware

- Autoclaved glassware (treated with Diethyl Pyrocarbonate (DEPC) if necessary)

- RNase-free water and buffers

Methodology:

- Workspace Decontamination: Before and after experiments, thoroughly clean all work surfaces, pipettors, and equipment with an RNase-deactivating reagent.

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Always wear disposable gloves and change them frequently, especially after touching non-sterile surfaces like door handles or phones.

- Use of Consumables: Opt for single-use, certified RNase-free plasticware. Treat reusable non-disposable plasticware with 0.1 M NaOH/1 mM EDTA, followed by rinsing with RNase-free water.

- Sample Processing: Work quickly to limit RNA exposure to the environment. Keep samples on ice at all times unless using a specific room temperature stabilization reagent.

- Reagents: Use only reagents certified as RNase-free. Prepare small aliquots to avoid repeated freezing and thawing of stock solutions.

Objective: To outline a "fit-for-purpose" process for validating analytical methods used to measure biomarkers, ensuring data reliability for its intended context of use.

Materials:

- Appropriate analytical instrumentation (e.g., LC-MS, ELISA plate reader)

- Quality Control (QC) samples

- Surrogate matrix or surrogate analytes for endogenous biomarkers

Methodology:

- Define Context of Use (COU): Clearly state the purpose of the biomarker measurement (e.g., exploratory research, patient stratification, or surrogate endpoint).

- Select Validation Parameters: Based on the COU, determine which performance characteristics need validation. Key parameters often include:

- Accuracy and Precision: Assess the closeness of the measured value to the true value and the reproducibility of the measurement.

- Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ): Determine the lowest concentration that can be reliably measured with acceptable accuracy and precision.

- Parallelism: Demonstrate that the dilution of a sample gives a response parallel to the standard curve, confirming accurate measurement in the biological matrix.

- Execute Validation Plan: Perform experiments to test the selected parameters, often using a surrogate matrix if the biomarker is endogenous.

- Documentation: Comprehensively document all procedures, results, and acceptance criteria met.

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Sample Processing Workflow

RNase Contamination Prevention

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Sample Integrity

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| RNase Inactivation Reagents | Deactivates RNase enzymes on surfaces and equipment. | Creating an RNase-free workspace before RNA extraction [44]. |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents (e.g., RNAprotect) | Immediately stabilizes RNA integrity at room temperature, halting degradation. | Preservation of RNA in collected tissue or cell samples before homogenization [44]. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Inhibits a broad spectrum of protease enzymes to prevent protein degradation. | Added to lysis buffers during protein extraction from tissues or cells. |

| EDTA | Chelates divalent cations (e.g., Mg²⁺), which can catalyze RNA hydrolysis. | A component of buffers to chemically stabilize RNA during storage [44]. |

| PAXgene Tubes | Contains reagents that stabilize intracellular RNA in whole blood. | Standardized collection of blood samples for gene expression analysis [44]. |

| Surrogate Matrix | A defined protein solution or buffer used to create standard curves for endogenous biomarkers. | Quantifying biomarkers in serum where the native matrix is complex [45]. |

Navigating Analytical Techniques and Platforms for Different Biomarker Classes

FAQs: Core Concepts and Validation

Q1: What is the critical difference between analytical validation and clinical validation for a biomarker?

A1: Analytical validation and clinical validation serve distinct purposes in the biomarker development pipeline.

- Analytical Validation is the process of "Establishing that the performance characteristics of a test, tool, or instrument are acceptable in terms of its sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, precision, and other relevant performance characteristics using a specified technical protocol." This step ensures the test method itself is technically reliable and reproducible [20].

- Clinical Validation, in contrast, is the process of "Establishing that the test, tool, or instrument acceptably identifies, measures, or predicts the concept of interest." This confirms the biomarker's usefulness for its specific intended purpose, such as diagnosing a disease or predicting treatment response [20].

Q2: How does the intended "Context of Use" influence my choice of analytical platform?

A2: The Context of Use (COU) is a concise description of the biomarker's specified purpose, including its category and how it will inform decisions. The COU is critical because it dictates the required sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility of the analytical method, which in turn influences platform selection [20].