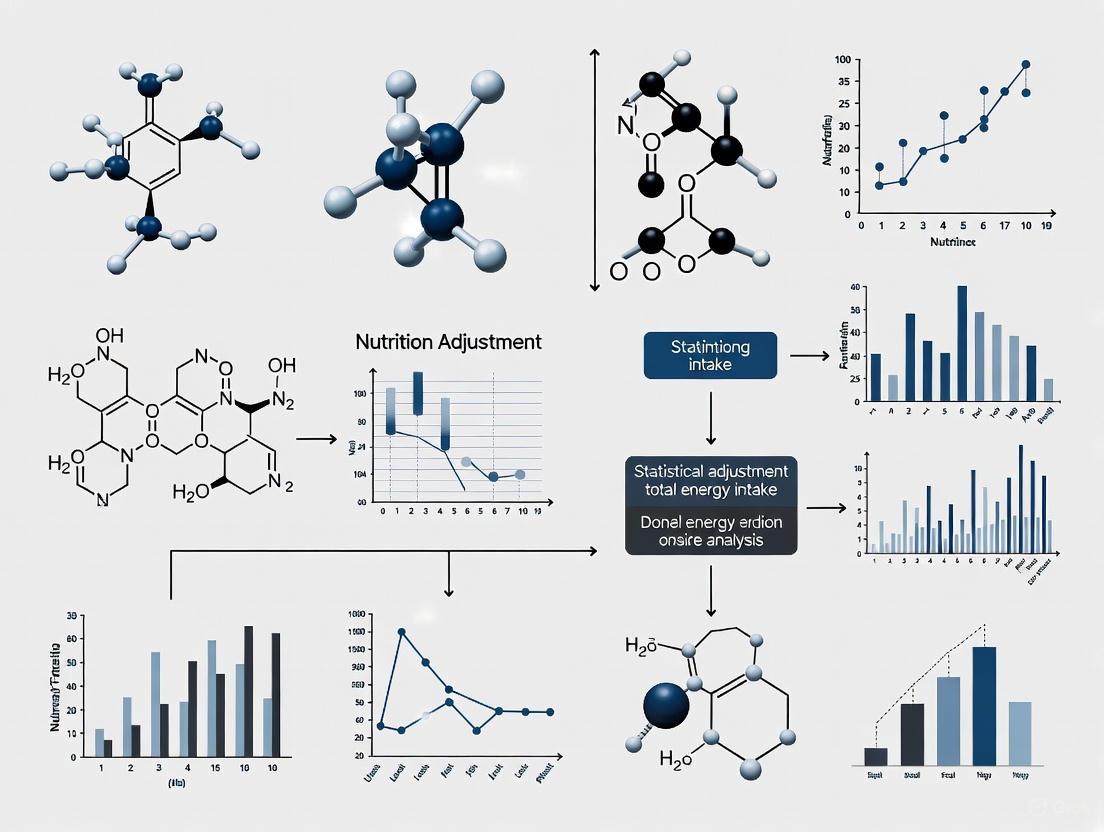

Statistical Adjustment for Total Energy Intake: A Foundational Guide for Robust Nutritional Epidemiology and Clinical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the statistical adjustment of total energy intake, a critical methodological step for researchers and drug development professionals.

Statistical Adjustment for Total Energy Intake: A Foundational Guide for Robust Nutritional Epidemiology and Clinical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the statistical adjustment of total energy intake, a critical methodological step for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational rationale for energy adjustment to control for confounding and reduce extraneous variation in diet-disease association studies. The content explores established and novel methodological approaches, including the nutrient density and residual methods, and delves into troubleshooting pervasive issues like dietary misreporting, offering strategies for identification and correction using tools like the Goldberg cut-offs and doubly labeled water. Finally, it reviews validation techniques and comparative frameworks to assess the performance of different adjustment methods, equipping scientists with the knowledge to enhance the validity and reliability of their nutritional analyses.

Why Energy Adjustment is Non-Negotiable in Nutritional Research

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is adjusting for total energy intake so critical in nutritional research?

Failure to account for total energy intake can obscure true associations between nutrients and disease risk or even reverse the direction of an association. This is because intakes of most specific nutrients are correlated with total energy intake, creating confounding. Proper adjustment controls for this confounding, reduces extraneous variation, and helps predict the effect of realistic dietary interventions [1].

Q2: What are the primary methods for energy adjustment, and how do I choose?

Researchers commonly use four models, each with a different target estimand (the quantity being estimated). The choice depends on your specific research question [2].

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each model:

| Model Name | Core Adjustment Method | Target Estimand | Key Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Model | Includes both the nutrient and total energy intake as covariates. | Average Relative Causal Effect | Estimates the effect of substituting the nutrient for the weighted average of all other energy sources. |

| Energy Partition Model | Includes the nutrient and the energy from all other sources. | Total Causal Effect | Estimates the effect of adding the nutrient while holding all other energy sources constant. |

| Nutrient Density Model | Expresses the nutrient as a proportion of total energy (e.g., % of calories). | Obscure / Rescaled Relative Effect | Attempts to estimate a relative effect, but its interpretation is not straightforward. |

| Residual Model | Uses the residuals from a regression of the nutrient on total energy intake. | Average Relative Causal Effect | Mathematically identical to the Standard Model; it indirectly adjusts for total energy. |

Q3: My model is adjusted for total energy, but I still suspect confounding. Why?

This is a common limitation. Adjusting for a summary variable like total energy only partially accounts for confounding if the other individual dietary components have distinct effects on the outcome. This can introduce "composite variable bias." A more robust solution is the "all-components model," which simultaneously adjusts for all major dietary components. This approach can provide less biased estimates of both total and relative causal effects [2].

Q4: How can errors in measuring energy intake affect my results?

Energy intake is notoriously difficult to measure accurately. Dietary surveys, like 24-hour recalls, are often prone to substantial misreporting and tend to underestimate actual calorie intake [3]. This misreporting can introduce significant uncertainty and bias into your analysis, affecting the consistency and comparability of dietary assessment [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Conflicting results between studies using different adjustment models.

Solution: This is often not a true conflict but a consequence of different models answering different questions.

- Diagnose the Cause: Identify the energy adjustment model used in each study. The Standard and Energy Partition models estimate different effects (substitution vs. addition) and should not be directly compared [2].

- Apply the Correct Interpretation: Refer to the table in FAQ A2. A study using the Standard Model answers: "What is the effect of increasing nutrient A while decreasing the average of all other nutrients to keep total energy constant?" A study using the Energy Partition Model answers: "What is the effect of adding more of nutrient A to the diet without changing anything else?" [2].

- Prevent in Meta-Analyses: When conducting systematic reviews or meta-analyses, ensure you do not inappropripool estimates from studies that used different models, as this can create the appearance of heterogeneity where none exists [2].

Problem: Determining the most accurate method to estimate energy requirements.

Solution: For population-level studies, consider moving beyond outdated factorial methods.

- Recommended Method: Use predictive equations for estimating energy requirements (EERs) derived from a comprehensive database of doubly labeled water (DLW) studies. The equations developed by the US National Academies of Sciences (2023) are considered current best practice [3].

- Implementation: These equations are differentiated by age, sex, and physical activity level and are dependent on age, height, and weight. Pair them with anthropometric data (body weight, height) to estimate energy requirements [3].

- Validation: This method has been validated against external DLW data and provides a proxy for energy intake that reflects observed anthropometric measures, bypassing some of the misreporting issues in dietary surveys [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

The following table lists key components for a rigorous study investigating diet-disease relationships.

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Validated Dietary Assessment Tool | To measure the exposure (e.g., 24-hour recalls, Food Frequency Questionnaires). Essential for collecting data on nutrient intake and total energy. |

| Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) | The gold-standard method for objectively measuring total energy expenditure in free-living individuals, used to validate energy intake data [3]. |

| Anthropometric Measurement Tools | To measure outcomes and confounders (e.g., calibrated scales, stadiometers, DEXA for body composition). Critical for assessing BMI, waist circumference, and fat-free mass [4]. |

| Causal Diagram (DAG) | A conceptual tool to map out hypothesized causal relationships between the nutrient, outcome, total energy, and other confounders. This is crucial for selecting appropriate adjustment variables [2]. |

| "All-Components" Model | A statistical model that simultaneously adjusts for intake of all major dietary components (protein, fat, carbohydrates, etc.) to provide a less biased estimate than models using only total energy [2]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Assessing Energy Intake, Expenditure, and Balance in a Cohort

This retrospective cross-sectional design can be used to investigate associations between energy balance and health outcomes like obesity [4].

- 1. Participant Recruitment: Select participants using a multistage random sampling technique to ensure representativeness. Exclude pregnant or lactating individuals and those unable to provide consent [4].

- 2. Data Collection:

- Energy Intake: Collect dietary data via multiple, non-consecutive 24-hour dietary recalls. Calculate total energy and nutrient intake using a standardized food composition database [4].

- Anthropometry: Measure weight, height, and waist circumference using calibrated equipment following a strict protocol to calculate Body Mass Index (BMI) and identify abdominal obesity [4].

- Energy Expenditure: Calculate Total Energy Expenditure (TEE) as the sum of:

- Resting Energy Expenditure (REE): Estimate using predictive equations.

- Energy Expenditure of Activity (EEA): Assess using the WHO Global Physical Activity Questionnaire or accelerometers.

- Diet-Induced Thermogenesis: Typically estimated as a percentage (e.g., ~10%) of TEE [4].

- 3. Data Analysis:

- Calculate Energy Balance as:

Energy Intake - Total Energy Expenditure. - Use t-tests and ANOVA to compare numerical variables across groups.

- Employ logistic regression to evaluate factors associated with a positive energy balance [4].

- Calculate Energy Balance as:

Quantitative Data on Energy Intake and Imbalance

The following table summarizes key findings from recent global and cohort studies to provide context for expected values.

| Parameter | Study Population | Value (Mean ± SD or as stated) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Avg. Energy Intake (2020) | Global Population | 2160 kcal/day (95% CI: 2100 to 2210) | Estimated via anthropometric measures [3]. |

| Global Avg. Energy Imbalance (2020) | Global Population | +80 kcal/day (95% CI: 70 to 100) | Intake above requirements for healthy body weight [3]. |

| Total Energy Intake | Nigerian Young Adults (n=240) | 2416.0 ± 722.7 kcal/day [4] | |

| Total Energy Expenditure | Nigerian Young Adults (n=240) | 2195.5 ± 384.5 kcal/day [4] | |

| Resulting Energy Balance | Nigerian Young Adults (n=240) | +220.5 ± 787.3 kcal/day [4] | 68.8% of participants had a positive balance [4]. |

| Energy Balance with Obesity | Nigerian Adults with Obesity | +302.0 ± 1300.2 kcal/day [4] | Significantly higher than those without obesity. |

Model Relationships and Causal Pathways

Causal Diagram of Dietary Composition

Energy Adjustment Model Workflow

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Bias in Energy Intake Analysis

Problem: Inconsistent effect estimates for nutrient-outcome relationships across different statistical models.

Explanation: In nutritional research, individual dietary components are parts of a compositional whole. Total energy intake is a collider variable, meaning it is causally influenced by both your nutrient of interest and all other nutrients. Adjusting for it in statistical models can induce spurious associations if not handled properly [2].

Solution: Use the "all-components model" that simultaneously adjusts for all other dietary components instead of relying solely on total energy intake. This approach provides less biased estimates of both total and average relative causal effects [2].

Steps:

- Collect data on all major dietary components, not just your nutrient of interest

- In your regression model, include all dietary components simultaneously

- Avoid adjusting only for total energy intake, which creates collider bias

- Use directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) to map hypothesized causal relationships before analysis

Guide 2: Controlling for Extraneous Variation in Experimental Outcomes

Problem: Unmeasured variables affecting both your independent and dependent variables.

Explanation: Extraneous variables are any variables you're not investigating that can potentially affect your research outcomes. When these variables are associated with both your exposure and outcome, they become confounding variables that provide alternative explanations for your results [5].

Solution: Implement multiple control strategies at both design and analysis stages.

Steps:

- Randomization: Randomly assign participants to experimental conditions to evenly distribute extraneous variables [6]

- Elimination: Hold variables constant throughout the study (e.g., standardize laboratory conditions, use identical measurement protocols) [6]

- Statistical Control: Measure and adjust for extraneous variables in your analysis using regression or ANCOVA [5]

- Matching: Match participants across groups based on key extraneous variables

Guide 3: Forecasting Causal Effects from Observational Data

Problem: Needing to predict intervention effects without conducting randomized trials.

Explanation: Under certain conditions, longitudinal observational studies can forecast causal effects of hypothetical interventions using structural equation modeling and DAG-based approaches, even when the intervention hasn't been implemented [7].

Solution: Use cross-lagged panel models with proper causal identification assumptions.

Steps:

- Collect longitudinal data with multiple pre-intervention time points

- Specify a DAG representing your causal theory

- Use structural equation modeling to estimate parameters

- Apply the do-operator or related methods to simulate interventions

- Forecast post-intervention outcomes using the estimated model parameters

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What's the difference between extraneous and confounding variables?

A: An extraneous variable is any variable you're not investigating that can potentially affect your dependent variable. A confounding variable is a specific type of extraneous variable that is associated with both your independent and dependent variables, creating spurious associations [5].

Q: Which energy adjustment method should I use in nutritional epidemiology?

A: Current research suggests the "all-components model" that simultaneously adjusts for all dietary components outperforms traditional approaches. The four common models estimate different causal quantities [2]:

- Standard model: Average relative causal effect (substitution effect)

- Energy partition model: Total causal effect

- Nutrient density model: Obscure interpretation attempting relative effect

- Residual model: Mathematically identical to standard model

Q: How can I distinguish between forecasting intervention effects and predicting outcomes?

A: Forecasting intervention effects involves estimating what would happen if you actively changed a variable, while prediction involves estimating future values under natural progression. Forecasting requires causal assumptions and methods like Pearl's do-calculus, while prediction can use purely associative patterns [7].

Q: What are the most effective ways to control extraneous variation?

A: The most effective approaches include [5] [6]:

- Randomization (balances all potential extraneous variables)

- Elimination (holding variables constant)

- Statistical control (measuring and adjusting in analysis)

- Matching (ensuring comparable groups)

- Blinding (reducing experimenter effects and demand characteristics)

Quantitative Data Tables

| Model Type | Target Estimand | Interpretation | Bias in Absence of Confounding | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Model | Average relative causal effect | Substitution effect | Biased | Composite variable bias |

| Energy Partition Model | Total causal effect | Additive effect | Unbiased | Residual confounding when other nutrients have distinct effects |

| Nutrient Density Model | Obscure | Attempts relative effect rescaling | Biased | Difficult interpretation |

| Residual Model | Average relative causal effect | Substitution effect | Biased | Mathematically identical to standard model |

| All-Components Model | Total and relative effects | Both additive and substitution | Reduced bias | Requires complete dietary data |

| Control Method | Application Context | Effectiveness | Implementation Complexity | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomization | Experimental studies | High | Medium | Gold standard but not always ethical or feasible |

| Elimination | All study types | Medium-High | Low | Reduces generalizability |

| Statistical Control | Observational studies | Medium | High | Requires measurement of confounders |

| Matching | Observational studies | Medium | Medium | Can be computationally intensive |

| Blinding | Clinical trials | High | Low | Reduces experimenter and participant bias |

| Restriction | All study types | Medium | Low | Simplifies analysis but reduces sample size |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing the All-Components Model for Energy Adjustment

Purpose: To estimate unbiased causal effects of individual dietary components on health outcomes.

Methodology:

- Collect dietary intake data for all major nutrient components

- Calculate total energy intake as the sum of all components

- Specify a directed acyclic graph (DAG) representing causal hypotheses

- Fit a multivariate regression model including all dietary components simultaneously:

Outcome ~ β₁Nutrient₁ + β₂Nutrient₂ + ... + βₖNutrientₖ + Covariates + ε - Interpret coefficients as the effect of increasing each nutrient while keeping all others constant

Validation: Test model assumptions including linearity, additivity, and error structure. Check for multicollinearity using variance inflation factors (VIF).

Protocol 2: Cross-Lagged Panel Design for Forecasting Intervention Effects

Purpose: To forecast causal effects of interventions using longitudinal observational data.

Methodology [7]:

- Collect repeated measures of exposure (X) and outcome (Y) variables at multiple time points

- Specify and estimate a cross-lagged panel model:

- Verify model fit using standard indices (CFI > 0.95, RMSEA < 0.06, SRMR < 0.08)

- Use the estimated parameters to forecast effects of hypothetical interventions using the do-operator

- Calculate forecasted mean, variance, and probability of outcomes falling within acceptable ranges

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Causal Inference Studies

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| DAGitty Software | Visualize and analyze causal diagrams | Identify minimal sufficient adjustment sets for confounding control |

| Structural Equation Modeling Software | Estimate complex causal models | Implement cross-lagged panel designs for forecasting intervention effects |

| Dietary Assessment Tools | Measure nutritional exposures | Collect comprehensive nutrient data for all-components models |

| Randomized Control Trial Protocols | Gold standard for causal inference | Establish true causal effects for validation of observational methods |

| Sensitivity Analysis Tools | Assess robustness to unmeasured confounding | E-value calculations and simulation-based methods |

| Directed Acyclic Graphs | Formalize causal assumptions | Visualize and test causal hypotheses before analysis |

The Energy-Nutrient-Disease Triad describes the interconnected relationship between chronic low energy availability, its subsequent impact on nutrient metabolism, and the development of multi-system physiological disorders. This framework, evolved from the Female Athlete Triad, now encompasses the broader syndrome known as Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs) [8] [9]. REDs occurs when an individual's energy intake is insufficient to support the energy expended by exercise, leaving inadequate energy to support the body's normal physiological functions [8]. This energy deficit triggers a cascade of endocrine adaptations that disrupt nutrient absorption and utilization, ultimately leading to impaired bone health, metabolic rate, immunity, and cardiovascular function [8] [10] [9].

Core Components of the Triad

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected, cyclical relationship between the three core components of the Energy-Nutrient-Disease Triad.

Low Energy Availability (LEA)

Low Energy Availability (LEA) is the cornerstone of the triad, defined as the state where dietary energy intake is insufficient to cover the cost of exercise expenditure, leaving inadequate energy to support homeostatic functions [9]. It is calculated as:

Energy Availability (EA) = (Energy Intake (kcal) - Exercise Energy Expenditure (kcal)) / Fat-Free Mass (kg) [9]

Chronic LEA is the primary etiological driver for the development of REDs [11]. An EA below 30 kcal/kg FFM/day is a commonly referenced threshold for LEA, though precise clinical cut-offs are still refined [12].

Nutrient and Metabolic Dysregulation

The body's response to LEA is a down-regulation of metabolic processes to conserve energy. This includes:

- Suppressed Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR): Measured RMR is often significantly lower than predicted values [9] [11].

- Hormonal Alterations: Marked reductions in triiodothyronine (T3), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and leptin, indicating a catabolic state [11].

- Menstrual Dysfunction: In females, hypothalamic suppression leads to reduced estrogen and progesterone production, causing functional hypothalamic amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea [10] [9].

- Micronutrient Deficiencies: Inadequate intake often leads to suboptimal levels of bone-supporting nutrients like Vitamin D, Calcium, and Iron [9].

Multi-System Disease Manifestations

Prolonged LEA and metabolic dysregulation lead to clinical disease manifestations across multiple systems [8]:

- Impaired Bone Health: Low estrogen and nutrient deficiencies result in decreased bone mineral density (BMD), osteopenia, osteoporosis, and a significantly elevated risk of stress fractures [8] [10].

- Endocrine and Reproductive Dysfunction: Includes menstrual irregularities and low libido [8].

- Immunological and Cardiovascular Compromise: Increased susceptibility to illness and potential long-term heart damage [8].

- Psychological Effects: Increased incidence of irritability, depression, and anxiety [8].

Common Methodological Challenges & Troubleshooting

Researchers studying the Energy-Nutrient-Disease Triad frequently encounter specific methodological issues. The following table outlines common problems and their solutions.

| Challenge | Potential Impact on Data | Troubleshooting Guide & Methodological Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Inaccurate Energy Intake Assessment [13] [9] | Systematic under-reporting of food intake, leading to misclassification of LEA. | Use multiple dietary assessment tools (e.g., multiple 24-hr recalls + FFQ). Employ statistical correction using regression calibration where possible [13]. Incorporate objective biomarkers (e.g., plasma vitamin C for fruit/vegetable intake) as surrogate measures to correct for measurement error [13]. |

| Calculating Exercise Energy Expenditure (EEE) [9] | High variability in EEE estimation introduces significant error into the EA equation. | Utilize device-based measures (heart rate monitors, accelerometers, GPS) with individual calibration over self-report logs. For precision, use the adjusted EEE method: subtract resting metabolic rate during the exercise period from total exercise cost [9]. |

| Diagnosing REDs & Triad Severity [11] | Inconsistent use of biomarkers leads to challenges in comparing studies and accurately staging syndrome severity. | Adopt a standardized tool like the IOC REDs Clinical Assessment Tool-Version 2 (REDs CAT2) [11]. This provides a structured framework for assessing risk (from low to high) based on a combination of biomarkers, clinical symptoms, and performance metrics. |

| Biomarker Variability & Selection [11] | Lack of a single diagnostic biomarker; confusion over which markers are most informative. | Focus on a panel of biomarkers. The most frequently used and informative markers in research include Bone Mineral Density (BMD) via DEXA, hormones (T3, estradiol, testosterone), and hematological markers (ferritin, hemoglobin) [11]. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Assessing Energy Availability and REDs Risk

This workflow provides a step-by-step guide for a comprehensive assessment of an individual's status within the Energy-Nutrient-Disease Triad.

1. Participant Screening & Questionnaires:

- Tools: Administer the Low Energy Availability in Females Questionnaire (LEAF-Q) to assess physiological symptoms and the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) or Brief EDs in Athletes Questionnaire (BEDA-Q) to evaluate disordered eating behaviors [9] [11].

- Purpose: Identifies at-risk individuals for further testing.

2. Dietary and Exercise Assessment:

- Dietary Intake: Collect at least 3 days of dietary intake (including at least one weekend day) using a detailed food diary or multiple 24-hour recalls. Data should be analyzed using validated nutritional software (e.g., ESHA Food Processor) [14] [9].

- Exercise Energy Expenditure (EEE): Record all exercise for the same days using a detailed log. EEE should be calculated using MET values from the Compendium of Physical Activities or, preferably, data from individual calibrated wearable devices [14] [9].

3. Body Composition Analysis:

- Method: Perform a Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA) scan to obtain accurate measurements of Fat-Free Mass (FFM), fat mass, and Bone Mineral Density (BMD) [14] [10].

- Application: FFM is used as the denominator in the EA equation. BMD Z-scores below -1.0 in athletes are considered indicative of low bone density [10].

4. Calculation of Energy Availability:

- Formula: Use the standard EA equation. Input total energy intake (from step 2), EEE (from step 2), and FFM (from step 3). Compare the result to established thresholds [9].

5. Biochemical & Hormonal Biomarker Analysis:

- Blood Collection: Conduct a fasted blood draw.

- Key Analytes:[

citation:4] [11]

- Hormones: Triiodothyronine (T3), luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), estradiol (for females), testosterone, prolactin.

- Metabolic Markers: Resting Metabolic Rate (via indirect calorimetry if available).

- Nutrient Status: Iron panel (ferritin, transferrin), Vitamin D (25(OH)D), Calcium.

6. Synthesis and Diagnosis:

- Tool: Input all collected data (questionnaire scores, EA value, hormone levels, BMD results, clinical symptoms) into the IOC REDs CAT2 tool to determine the overall risk category (e.g., low, moderate, high) and guide management [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Tool / Reagent | Primary Function in Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA) [14] [10] | Gold-standard measurement of body composition (Fat-Free Mass) and Bone Mineral Density (BMD). | Critical for calculating EA denominator and diagnosing the bone health component of the triad. |

| Indirect Calorimeter [11] | Objective measurement of Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR) via oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production. | Used to identify metabolic suppression (measured RMR << predicted RMR), a key sign of prolonged LEA. |

| Validated Questionnaires (LEAF-Q, EDE-Q) [9] [11] | Low-burden, initial screening for symptoms of LEA and disordered eating psychopathology. | Essential for large-scale cohort studies and identifying at-risk populations for further investigation. |

| Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Kits | Quantification of specific biomarkers from blood, saliva, or urine samples (e.g., hormones like T3, estradiol, IGF-1). | Allows for high-throughput analysis of endocrine alterations associated with LEA. |

| Nutritional Analysis Software (e.g., ESHA Food Processor) [14] | Converts food record data into estimated intakes of energy, macronutrients, and micronutrients. | Standardizes dietary intake analysis. Must be used with up-to-date food composition databases. |

| Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA) [15] | Field-based assessment of body composition, providing estimates of fat mass and fat-free mass. | Less accurate than DEXA but more accessible. Can be useful for tracking longitudinal changes. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the critical distinction between the Female Athlete Triad and REDs? A: The Female Athlete Triad is a specific subset of REDs, focusing on three interrelated components in females: low energy availability, menstrual dysfunction, and low bone mineral density [8] [10]. REDs is a broader, more comprehensive syndrome that recognizes the multi-system physiological impairments caused by LEA and affects athletes of all genders [8] [9].

Q2: How can we statistically correct for the known measurement error in self-reported dietary data? A: This is a core challenge in nutritional epidemiology. Advanced statistical methods like regression calibration can be used [13]. This technique uses a reference measurement (e.g., data from a more detailed diet diary or a recovery biomarker like doubly labeled water for energy intake) in a subset of the cohort to estimate and correct for the bias in the main instrument (e.g., an FFQ) [13]. The use of surrogate biomarkers (e.g., plasma vitamin C, nitrogen) that correlate with intake can also be incorporated into measurement error models to improve accuracy [13].

Q3: Which blood biomarkers are considered most critical for diagnosing and monitoring REDs in a research setting? A: According to reviews of current methodologies, the most frequently utilized and informative biomarkers include [11]:

- Triiodothyronine (T3): A key marker of metabolic adaptation.

- Hormones for Menstrual Status: Luteinizing Hormone (LH), Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH), and Estradiol in females; Testosterone in males.

- Bone Turnover Markers: Such as P1NP (formation) and CTX (resorption).

- Iron Panel: Ferritin and hemoglobin to assess for anemia, which can compound fatigue.

- Vitamin D (25-OH D): Crucial for bone health and often deficient.

Troubleshooting Guide: Statistical Models in Nutritional Research

This guide helps researchers identify and correct for common pitfalls in statistical models used in nutritional epidemiology, particularly when adjusting for total energy intake.

Q1: My model shows a significant effect of a nutrient, but I suspect it might be confounded by total energy intake. How can I investigate this?

Problem: A statistically significant result may be misleading if the model does not properly account for total energy intake, as overall diet can be a confounder [2].

Symptoms:

- The effect size of the nutrient changes substantially when total energy intake is added to the model.

- The direction of the association (positive/negative) reverses after adjustment.

- You know from existing literature that the nutrient is highly correlated with total energy intake in your study population.

Resolution: Follow this diagnostic workflow to identify the appropriate model and check for confounding:

Q2: After adjusting for baseline values in my analysis of change from baseline, the type I error rate seems inflated. What went wrong?

Problem: In pharmacogenomic (PGx) studies analyzing quantitative change, failing to adjust for baseline values can inflate type I error for genetic variants associated with the baseline trait [16] [17].

Symptoms:

- Anomalously high false-positive rates in your genome-wide association study (GWAS) of change from baseline.

- The baseline value of the trait is both associated with the genotype and is a predictor of the change from baseline (i.e., it acts as a mediator) [16] [17].

Resolution:

- Diagnose: Check if your baseline trait is associated with any genetic variants in your dataset. Also, verify the correlation between the baseline and the change-from-baseline values; a negative correlation is common [17].

- Act: The recommended primary analysis is to use a baseline-adjusted model to control for this mediator effect and maintain a correct type I error rate [16] [17]. If measurement error is still suspected of causing inflation, a baseline-unadjusted model can be run for diagnostic comparison [17].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the core consequence of using an unadjusted or incorrectly adjusted model? The primary consequence is biased estimation. This can either obscure a true association (leading to false negatives) or, more severely, reverse the direction of an association, creating a false positive for an effect that is the opposite of reality [2]. This heterogeneity in estimands can also invalidate meta-analyses if different studies use different adjustment methods [2].

Q: What is the "all-components model" and when should I use it? The "all-components model" is an approach that simultaneously adjusts for the intake of all other dietary components besides the one you are studying [2]. It is recommended to obtain less biased estimates of both the total causal effect and the average relative causal effect, as it avoids the residual confounding that can occur when using summary variables like total energy or remaining energy intake [2].

Q: In a PGx study, when might a baseline-unadjusted model have more power than an adjusted one? Simulations show that a baseline-unadjusted model may appear to have higher power when the genetic effect on the baseline trait is in the opposite direction from the genetic effect on the change from baseline [17]. However, this apparent power advantage comes at the cost of an inflated type I error rate if the baseline acts as a mediator, making the results unreliable [17].

The table below summarizes the four common models for energy adjustment, their target estimands, and interpretations, which is crucial for selecting the right one and avoiding erroneous conclusions [2].

| Model Name | Core Specification | Target Estimand | Key Interpretation | Primary Risk/Consequence of Misuse |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Model | Nutrient; Total Energy | Average Relative Causal Effect | Effect of substituting the nutrient for the weighted average of other energy sources [2]. | Biased estimates even without confounding; estimates a substitution effect, not a total effect [2]. |

| Energy Partition Model | Nutrient; Remaining Energy | Total Causal Effect | The total effect of increasing the nutrient while keeping all other intakes constant (an "additive" effect) [2]. | Unbiased only with no confounding or if all other nutrients have equal effects; otherwise, residual confounding [2]. |

| Nutrient Density Model | Nutrient/Total Energy | Obscure | Attempts to estimate a relative effect rescaled as a proportion of total energy [2]. | An obscure causal interpretation that makes results difficult to compare with other models [2]. |

| Residual Model | Residual of Nutrient ~ Total Energy | Mathematically identical to the Standard Model [2]. | Identical to the Standard Model—a substitution effect [2]. | Same as the Standard Model; provides no additional benefit [2]. |

Experimental Protocol: Comparing Energy Adjustment Models

Objective: To empirically demonstrate how different energy adjustment models can obscure or reverse the estimated effect of a specific nutrient (e.g., sugars) on a health outcome (e.g., fasting plasma glucose).

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Utilize observational nutritional data with detailed dietary component intake and a measured health outcome.

- Model Fitting: Fit the four primary models (Standard, Energy Partition, Nutrient Density, Residual) to estimate the effect of the chosen nutrient [2].

- "All-Components" Model: As a more robust comparison, fit a model that includes the exposure nutrient and all other major dietary components simultaneously [2].

- Comparison & Analysis: Compare the estimated coefficient, direction, and statistical significance of the exposure nutrient across all five models.

Key Measurements & Outputs:

- Primary Output: A table of regression coefficients for the nutrient of interest from each model.

- Diagnostic Plot: A forest plot visualizing the point estimates and confidence intervals for the nutrient's effect across all models to easily see reversals or obscuring of effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) | A visual tool to map out and identify potential confounding variables, like total energy intake, based on prior subject knowledge [2]. |

| Compositional Data Analysis | A set of statistical methods recognizing that dietary data are "parts of a whole," preventing spurious findings when analyzing individual nutrients [2]. |

| Monte Carlo Simulations | A computational algorithm used to evaluate model performance (e.g., type I error, power) under controlled, known conditions before applying them to real data [2] [16]. |

| All-Components Model | The statistical model that adjusts for all individual dietary components to provide a less biased estimate of a nutrient's effect [2]. |

Core Statistical Models and Practical Application Techniques

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core distinction between the Nutrient Density and Energy Partition models? The core distinction lies in their target causal effects. The Energy Partition model is used to estimate the total causal effect of a nutrient—the effect of increasing the intake of that specific nutrient while the intake of all other nutrients remains constant [2]. In contrast, the Nutrient Density model attempts to estimate an average relative causal effect (a "substitution" effect), which represents the effect of increasing the energy intake from the exposure nutrient while simultaneously decreasing the intake from all other energy sources to keep total energy constant [2].

FAQ 2: Why do different energy adjustment models produce different results for the same exposure and outcome? Different models produce different results because each one implies a different causal estimand [2]. The models are mathematically distinct and answer subtly different research questions. For instance, the Standard and Residual models estimate a substitution effect, whereas the Energy Partition model estimates a total effect. This fundamental difference in the target of inference naturally leads to variation in the estimated coefficients, and pooling these different estimands in meta-analyses can threaten the validity of the conclusions [2].

FAQ 3: When should I use the "all-components model" instead of a traditional model? The all-components model—which involves simultaneously adjusting for all other individual dietary components—is generally recommended when your goal is to obtain the least biased estimate of either the total causal effect or the average relative causal effect [2]. Traditional models that adjust for summary measures like total energy or remaining energy intake are susceptible to residual confounding and composite variable bias, which occurs because these aggregates combine multiple nutrients that likely have distinct effects on the outcome. The all-components model avoids this information loss [2] [18].

FAQ 4: How can I handle suspected measurement error in total energy intake? While detailed methodologies for handling measurement error are beyond the scope of this guide, it is a critical consideration. Be aware that errors in the measurement of total energy intake can propagate differently across the various adjustment models, potentially biasing the results. Sensitivity analyses specific to the chosen model are recommended to assess the robustness of your findings to potential measurement error [18].

Comparison of Energy Adjustment Models

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, interpretations, and performance of the four common energy intake adjustment models, plus the alternative all-components model.

Table 1: Characteristics of Statistical Models for Energy Intake Adjustment in Nutritional Research

| Model Name | Model Formulation Example | Target Causal Estimand | Key Interpretation | Performance & Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Model | Outcome ~ exposure + total_energy |

Average Relative Causal Effect [2] | Effect of substituting the exposure for a weighted average of all other energy sources [2]. | Mathematically identical to the residual model. Can be biased even without confounding [2] [18]. |

| Energy Partition Model | Outcome ~ exposure + remaining_energy |

Total Causal Effect [2] | Effect of increasing the exposure while holding all other energy intake constant (an "additive" effect) [2]. | Unbiased only with no confounding or if all other nutrients have equal effects on the outcome [2]. |

| Nutrient Density Model | Outcome ~ (exposure / total_energy) |

Attempts to estimate a rescaled Average Relative Causal Effect [2] | Effect of the exposure expressed as a proportion of total energy [2]. | Interpretation can be obscure. Performance depends on specific formulation [2]. |

| Residual Model | 1. exposure ~ total_energy 2. Outcome ~ residual_from_step_1 |

Average Relative Causal Effect [2] | Effect of the exposure after removing its linear association with total energy (a "substitution" effect) [2]. | Mathematically identical to the standard model. Provides biased estimates even without confounding [2]. |

| All-Components Model | Outcome ~ exposure + nutrient_2 + ... + nutrient_n |

Total Causal Effect (when all other components are adjusted for) [2] | Isolates the effect of the exposure by directly accounting for all other known dietary components [2]. | Provides less biased estimates of both total and relative effects by avoiding information loss from variable aggregation [2] [18]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementing and Comparing Energy Adjustment Models

This protocol outlines the steps for a simulation-based analysis to implement and compare the performance of different energy adjustment models, as described in the associated research [2] [18].

1. Research Reagent Solutions Table 2: Essential Components for Simulation-Based Analysis

| Component/Variable | Description/Function |

|---|---|

| Simulated Dietary Data | A dataset containing simulated values for key nutrients (e.g., sugars, carbohydrates, fibre, fats, protein) and an outcome variable (e.g., fasting plasma glucose) [18]. |

R Statistical Software |

The programming environment used for data simulation, model fitting, and analysis (e.g., version 4.0.3 or higher) [18]. |

| Total Energy Intake | A variable calculated as the sum of energy from all simulated nutrient components, including the exposure [2] [18]. |

| Remaining Energy Intake | A variable calculated as the sum of energy from all simulated nutrient components, excluding the exposure nutrient [2] [18]. |

| Model Comparison Script | Code to run the unadjusted, standard, energy partition, nutrient density, residual, and all-components models and store their exposure coefficient estimates [18]. |

2. Step-by-Step Workflow

Diagram 1: Model comparison workflow

- Step 1: Data Simulation. Simulate a base dataset with variables for multiple nutrients (e.g., non-milk extrinsic sugars as the exposure, carbohydrates, fibre, fats, protein) and a continuous health outcome (e.g., fasting plasma glucose). It is advisable to simulate data under two primary scenarios: one with and one without the presence of confounding by common causes of diet [18].

- Step 2: Variable Calculation. Create two key derived variables:

total_energy: The sum of energy intake from all nutrient sources, including the exposure.remaining_energy: The sum of energy intake from all nutrient sources excluding the exposure [18].

- Step 3: Model Fitting. Fit the following statistical models to the same simulated dataset:

- Unadjusted:

Outcome ~ exposure - Standard:

Outcome ~ exposure + total_energy - Energy Partition:

Outcome ~ exposure + remaining_energy - Nutrient Density:

Outcome ~ (exposure / total_energy)or a multivariable version with additional adjustment fortotal_energy. - Residual: First, regress

exposure ~ total_energyand save the residuals. Second, regressOutcome ~ these_residuals. - All-Components:

Outcome ~ exposure + nutrient_2 + nutrient_3 + ... + nutrient_n(adjusting for all other simulated nutrients individually) [2] [18].

- Unadjusted:

- Step 4: Results Extraction. For each fitted model, store the regression coefficient and standard error (or confidence interval) for the exposure variable.

- Step 5: Performance Comparison. Compare the estimated exposure coefficients across models against the known "true" effect size set during the simulation. Assess which models recover the true effect with minimal bias under different confounding scenarios [18].

Protocol 2: Validating a Nutrient Density Score with Diet Quality

This protocol describes how to develop and validate a hybrid nutrient density score against an independent measure of overall diet quality, such as the Healthy Eating Index (HEI-2015) [19].

1. Research Reagent Solutions Table 3: Essential Components for Nutrient Density Score Validation

| Component/Variable | Description/Function |

|---|---|

| NHANES Dietary Data | Publicly available, nationally representative dietary intake data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (What We Eat in America component) [19]. |

| FPED Database | The Food Patterns Equivalents Database used to convert reported foods into USDA food groups (e.g., whole grains, dairy, fruit) for HEI-2015 calculation [19]. |

| FNDDS Database | The Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies, which provides the energy and nutrient values for foods reported in NHANES [19]. |

| HEI-2015 Score | The independent measure of diet quality, based on adherence to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, used as the validation metric [19]. |

2. Step-by-Step Workflow

Diagram 2: Score validation process

- Step 1: Data Preparation. Obtain and prepare dietary intake data from NHANES. This includes filtering the dataset (e.g., excluding participants with incomplete data, pregnant or lactating individuals) and calculating the HEI-2015 score for each participant using the FPED and FNDDS databases [19].

- Step 2: Component Selection. Define a set of candidate nutrients to encourage (e.g., protein, fiber, potassium), nutrients to limit (e.g., saturated fat, added sugar, sodium), and MyPlate food groups to encourage (e.g., whole grains, dairy, fruits, nuts, and seeds) [19].

- Step 3: Model Formulation & Regression. Construct a large number of potential hybrid NRF (NRFh) models with different combinations of the candidate components. The general form is

NRFh(x.y.z) = NRx + MPy - LIMz, whereNRxis the sum of x beneficial nutrients,MPyis the sum of y beneficial food groups, andLIMzis the sum of z nutrients to limit [19]. Run iterative regression analyses for each potential NRFh model score against the HEI-2015 score. - Step 4: Model Selection. Identify the specific NRFh model (e.g., NRFh3.4.3 or NRFh4.3.3) that explains the highest proportion of variance (R²) in the HEI-2015 score [19].

- Step 5: Validation. Test the performance and significance of the final selected NRFh model across different population subgroups (e.g., by age, gender, race/ethnicity) to ensure its robustness [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Resources

| Tool / Resource | Function in Research | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) | Provides nationally representative data on dietary intakes, health status, and anthropometric measures for analysis and model validation [20] [19]. | U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics [20]. |

| Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies (FNDDS) | Provides the energy and nutrient values for foods and beverages reported in dietary surveys like NHANES, essential for calculating nutrient intakes [20] [19]. | U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Agricultural Research Service [20]. |

| Food Patterns Equivalents Database (FPED) | Converts foods and beverages from FNDDS into USDA Food Patterns components (e.g., cup equivalents of fruit, ounce equivalents of whole grains), necessary for calculating diet quality scores like the HEI [20] [19]. | USDA Agricultural Research Service [20]. |

| Healthy Eating Index (HEI) | A validated, independent measure of overall diet quality used to assess compliance with dietary guidelines and validate nutrient profile models [19]. | USDA, National Cancer Institute [19]. |

| Doubly Labelled Water (DLW) Equations | The gold-standard method for estimating total energy expenditure. Predictive equations based on DLW studies provide the most accurate estimates of energy requirements for population studies [3]. | Committee on Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine) [3]. |

| R Statistical Software | The primary programming environment for simulating nutritional data, implementing different adjustment models, and conducting statistical analyses [18]. | R Project (r-project.org) with necessary packages for simulation and regression analysis. |

In nutritional epidemiology, the residual method is a established statistical technique used to adjust for total energy intake when investigating the effects of specific nutrients or foods on health outcomes. This adjustment is crucial because individuals who consume more of any single dietary component typically have a higher overall energy intake, which is itself influenced by body size, metabolic efficiency, and physical activity. Without proper adjustment, observed associations may be confounded by these factors. The residual method provides a way to isolate the effect of a specific dietary component from the effect of total energy intake, thereby assessing the component's role in the context of overall diet composition.

Core Concept: What is the Residual Method?

The residual method is an energy adjustment approach where the energy-adjusted intake of a nutrient is represented by the residuals from a regression model. In this model, absolute nutrient intake serves as the dependent variable, and total energy intake is the independent variable. The resulting residuals represent the variation in nutrient intake that is uncorrelated with total energy intake, effectively providing a measure of nutrient intake independent of total caloric consumption [21].

This method is particularly valuable because it accounts for two key challenges in nutritional research:

- It controls for confounding by body size, metabolic efficiency, and physical activity, for which total energy intake often serves as a proxy [2] [21].

- It helps mitigate measurement error inherent in self-reported dietary data, especially from food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) [21].

Table 1: Key Terminology in Energy Adjustment

| Term | Definition | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Residual Method | A statistical technique that uses residuals from a regression of nutrient intake on total energy intake to create an energy-adjusted variable [21]. | Isolates the effect of a specific nutrient from the effect of total energy intake. |

| Total Energy Intake | The total intake of calories from all dietary sources, including the nutrient of interest [2]. | Often used as a proxy for body size, metabolism, and physical activity. |

| Energy Partition Model | Adjusts for the remaining energy intake (calories from all sources excluding the exposure nutrient) [2]. | Aims to estimate the total causal effect of a nutrient. |

| Nutrient Density Model | Expresses the nutrient exposure as a proportion (percentage) of total energy intake [2] [21]. | Provides an intuitive measure of dietary composition. |

| Standard Model | Directly adjusts for total energy intake as a covariate in a regression model [2]. | Mathematically equivalent to the residual method but implemented differently. |

Step-by-Step Application Protocol

Step 1: Data Preparation and Assumption Checking

Before applying the residual method, ensure your dietary intake data has been collected using an appropriate instrument (e.g., FFQ, 24-hour recall) and has been cleaned. Check for the normality of the distribution for both the nutrient of interest and total energy intake. If the data are skewed, apply transformations (e.g., logarithmic, square root) to approximate a normal distribution, which satisfies a key assumption of linear regression [22].

Step 2: Model Specification and Regression

Run a simple linear regression model with the absolute intake of the nutrient or food group you are studying as the dependent variable (Y) and total energy intake as the independent variable (X).

The model is specified as:

Nutrient_i = β_0 + β_1 * Energy_i + ε_i

Where:

Nutrient_iis the absolute intake of the nutrient for individual iEnergy_iis the total energy intake for individual iβ_0is the regression interceptβ_1is the regression coefficient for energy intakeε_iis the error term, or residual, for individual i [21]

Step 3: Extracting the Residuals

The energy-adjusted values for the nutrient are the residuals (ε_i) from the regression model calculated in Step 2. Statistically, the residual for each individual is calculated as:

Residual_i = Observed Nutrient_i - Predicted Nutrient_i

Where the predicted nutrient intake is β_0 + β_1 * Energy_i [23] [21]. These residuals represent the difference between an individual's actual nutrient intake and the intake predicted by their total energy consumption. A positive residual indicates a higher-than-expected intake of the nutrient for a given energy intake, suggesting a diet denser in that nutrient.

Step 4: Utilizing the Adjusted Values in Downstream Analysis

The extracted residuals are now used as the exposure variable in your primary analysis model (e.g., a regression model with a health outcome as the dependent variable). Because these residuals are, by construction, uncorrelated with total energy intake, you do not need to adjust for energy again in the final model [24] [21].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and statistical relationship at the heart of the residual method:

Comparison with Other Energy Adjustment Methods

The residual method is one of several approaches for energy adjustment. It is mathematically equivalent to the "standard model," which includes the nutrient and total energy intake as simultaneous covariates in a multivariate regression model targeting the health outcome [2]. However, it differs conceptually and computationally from other common techniques.

Table 2: Comparison of Common Energy Adjustment Methods

| Method | Underlying Concept | Target Estimand | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residual Method | Uses the part of nutrient variation uncorrelated with total energy [21]. | Average Relative Causal Effect (a "substitution" effect) [2]. | Produces a variable uncorrelated with energy for use in subsequent models. | The derived variable (residual) lacks intuitive units, making interpretation less straightforward [2]. |

| Standard Model | Includes both the nutrient and total energy as covariates in the outcome model [2]. | Average Relative Causal Effect (a "substitution" effect) [2]. | Simple to implement and interpret as a standard multivariate model. | Can be difficult to communicate that it estimates a substitution effect. |

| Energy Partition Model | Adjusts for energy from all other sources (excluding the nutrient of interest) [2]. | Total Causal Effect (an "additive" effect) [2]. | Aims to estimate the effect of adding the nutrient to the diet without changing other components. | Provides unbiased estimates only in absence of confounding or if all other nutrients have equal effects [2]. |

| Nutrient Density Model | Expresses the nutrient as a proportion of total energy (e.g., % of calories from fat) [2] [21]. | Attempts to estimate a relative effect, but its interpretation can be obscure [2]. | Intuitively represents diet composition; easy to calculate and understand. | Can be biased if total energy intake is associated with the outcome [2]. |

Troubleshooting and Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: My residuals show a non-random pattern when plotted against predicted values. What does this mean?

A non-random pattern in your residuals (e.g., a funnel shape or a curved trend) indicates a violation of the linear regression assumptions. This could mean that the relationship between the nutrient and total energy intake is not linear. To address this, you can:

- Explore non-linear transformations (e.g., log, square root) of the nutrient and/or energy variables.

- Investigate the presence of outliers that may be unduly influencing the regression fit.

- Consider using non-parametric regression techniques, though these are less common in standard practice [25].

FAQ 2: How does the residual method help with measurement error in dietary assessment?

The residual method is particularly useful when using Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs), which cannot measure absolute energy intake accurately. It helps by assuming that individuals tend to misreport most foods and beverages in a similar direction and degree. By adjusting for total energy, the method partially corrects for this general tendency to under- or over-report, making the energy-adjusted nutrient values more reliable for diet-disease association analyses [21].

FAQ 3: When should I use the residual method versus the nutrient density method?

The choice of method should align with your research question.

- Use the residual method (or standard model) when your question is: "What is the effect of substituting a specific nutrient for the average of all other energy-contributing nutrients in the diet, while keeping total energy constant?" This is known as the "average relative causal effect" or "substitution effect" [2].

- Use the nutrient density method to simply describe the composition of the diet (e.g., the percentage of calories from saturated fat). However, be cautious as its causal interpretation in outcome models is less clear [2].

FAQ 4: The residual method and standard model are mathematically equivalent. Which one should I use in practice?

For simplicity and clarity in reporting, many researchers prefer the standard model. Including both the nutrient of interest and total energy intake as covariates in your final regression model for the health outcome is straightforward and avoids the extra step of creating and managing a residual variable. The results will be identical to those obtained using the two-step residual method [2] [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Dietary Pattern Analysis

Table 3: Key Methodological and Software Tools for Nutritional Analysis

| Tool Category | Example | Primary Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary Assessment Instrument | Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) [26] | Assesses habitual intake over a long-term period; cost-effective for large studies. |

| Dietary Assessment Instrument | 24-Hour Dietary Recall (24HR) [26] | Captures detailed recent intake (previous 24 hours); multiple non-consecutive recalls can estimate usual intake. |

| Statistical Software | SAS, R, STATA [27] [22] | Provides the computational environment for performing regression, calculating residuals, and implementing other energy adjustment models. |

| Validation Biomarker | Doubly Labeled Water (for energy) [28] | A recovery biomarker used as an objective reference to validate the accuracy of self-reported energy intake. |

| Validation Biomarker | Urinary Nitrogen (for protein) [28] | A recovery biomarker used as an objective reference to validate the accuracy of self-reported protein intake. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental purpose of adjusting for total energy intake in nutritional studies? Adjusting for total energy intake is crucial to account for confounding factors. An individual's overall food consumption level influences both their intake of specific nutrients and their health outcomes. Without this adjustment, it is difficult to determine whether an observed effect is due to a specific nutrient or simply the result of eating more food in general [29].

Q2: What are the primary statistical models for energy adjustment, and how do they differ? Researchers commonly use four main models, each with a different conceptual approach and interpretation [29]:

- The Standard Model: Adjusts for total energy intake as a covariate.

- The Nutrient Density Model: Expresses the nutrient intake as a proportion of total energy intake.

- The Residual Model: Uses the residuals from a regression of the nutrient intake on total energy intake.

- The Energy Partition Model: Adjusts for the energy intake from all other dietary components besides the nutrient of interest.

Q3: My model results change dramatically when I use different energy adjustment methods. Why does this happen, and which model should I trust? Different models estimate different causal effects, which explains why results can vary [29]. The "standard" and "residual" models estimate a substitution effect (e.g., the effect of replacing one nutrient with another while keeping total energy constant). The "energy partition" model estimates the total causal effect of the nutrient. The choice depends on your research question. There is no single "correct" model; the model must be selected based on the specific causal effect you wish to estimate [29].

Q4: How can I handle the issue of correlated dietary components (multicollinearity) in these models? Multicollinearity is a inherent challenge in nutritional data. To address this, the "all-components model" is recommended. This approach simultaneously includes all dietary components in the model, which can provide more accurate estimates of both total and average relative causal effects compared to the traditional four models [29].

Q5: A reviewer asked me to justify my choice of a nutrient density model (exposure per 1000 kcal) over other methods. How should I respond? You should explain that the nutrient density model attempts to estimate the average relative causal effect, rescaled as a proportion of total energy [29]. Justify your choice by aligning it with your research question—for instance, if your goal is to understand the effect of a nutrient's proportion in the diet, irrespective of total caloric intake. Acknowledge the model's limitations, particularly that its interpretation can be less straightforward than that of the standard or energy partition models [29].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Inconsistent Associations with Health Outcomes

Issue: The association between a nutrient and a health outcome changes direction or significance depending on whether you analyze absolute intake or energy-adjusted intake.

Solution: This is a known phenomenon. For example, a study on greenhouse gas emissions (GHGE) of diets found that:

- Higher absolute GHGE (per day) was associated with higher daily intake of all micronutrients.

- However, when expressed per 1000 kcal, higher GHGE was linked to lower micronutrient intake [30].

Interpretation Guide:

| Analysis Type | What It Typically Measures |

|---|---|

| Absolute Intake (per day) | The association with the total volume of food consumed. |

| Energy-Adjusted Intake (per 1000 kcal) | The association with the composition or quality of the diet. |

Your interpretation must match your model. The choice of model is not merely statistical but fundamentally affects the scientific question being asked [30] [29].

Problem 2: Misreporting of Dietary Intake Skews Data

Issue: Self-reported dietary data from tools like Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs) are prone to measurement error, including under-reporting of total energy intake, which can bias your results [3] [31].

Solution and Validation Strategies:

- Use Biomarkers: When possible, validate intake reports with objective biomarkers. For example, serum cotinine can validate smoking status [32], and vitamin D levels can corroborate dietary reports.

- Anthropometric Proxies: Consider using methods that derive energy intake from measured body weight, height, and physical activity levels. This approach mirrors actual energy consumption and can be used to test the consistency of self-reported data [3].

- Comprehensive FFQ Reporting: If using an FFQ, report validation metrics beyond a single correlation coefficient. Provide exposure-specific validation details and a clear description of energy adjustment methodologies to improve transparency [31].

Issue: Combining national food availability data (which often overestimates intake) with individual-level dietary surveys (which often underestimate intake) leads to inconsistent findings.

Solution:

- Use a Bridging Metric: Employ estimates derived from anthropometry (body weight, height) as a consistent benchmark. These estimates are designed to align with trends in body weight and can help reconcile discrepancies between different data sources, such as food balance sheets and dietary surveys [3].

- Leverage National Datasets: For US-based research, use standardized data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and its component What We Eat in America (WWEIA). These datasets use 24-hour dietary recalls and standardized nutrient databases like the Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies (FNDDS) and the Food Pattern Equivalents Database (FPED), ensuring internal consistency [20].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Energy Adjustment Models using NHANES Data

This protocol outlines how to apply different energy adjustment models using a standardized national dataset.

1. Data Source: Utilize the NHANES dataset, which includes 24-hour dietary recall data collected via the Automated Multiple Pass Method (AMPM) [32] [33]. 2. Key Variables:

- Exposure: Nutrient of interest (e.g., dietary choline [32]).

- Outcome: Health metric (e.g., Bone Mineral Density (BMD) [32]).

- Covariates: Total energy intake, demographic (age, sex, race), socioeconomic (Poverty-Income Ratio), and lifestyle factors (smoking status, physical activity) [32]. 3. Model Implementation: Fit a series of multivariate regression models with progressive adjustment [32]:

- Model 1: Adjusted for sex.

- Model 2: Additionally adjusted for age, BMI, and race.

- Model 3: Additionally adjusted for education, socioeconomic status, smoking, and physical activity.

- Model 4 (Fully Adjusted): Additionally adjusted for total energy intake and other relevant dietary components (e.g., calcium, vitamins). 4. Interpretation: Analyze how the coefficient for your nutrient of interest changes across models, noting the specific impact of adding total energy intake in the final model [32] [29].

Protocol 2: Assessing Diet Quality and Temporal Intake Patterns

This protocol measures the effect of meal timing and macronutrient quality, adjusted for total energy.

1. Data Preparation: Calculate the ratio of nutrient intake at dinner versus breakfast [33].

ΔRatio = (Nutrient at Dinner / Total Nutrient) - (Nutrient at Breakfast / Total Nutrient)

2. Exposure Variables: Create exposures for the difference in ratios (ΔRatio) for energy, high/low-quality carbohydrates, fats (saturated/unsaturated), and proteins (animal/plant) [33].

3. Outcome Variable: Obesity metrics (Body Mass Index, Waist Circumference) [33].

4. Statistical Analysis: Use multiple logistic and linear regression models, adjusting for total energy intake, age, sex, race, education, and other non-dietary confounders to isolate the effect of meal timing and composition [33].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Datasets and Tools

The following table lists key resources for conducting robust nutritional epidemiological research.

| Resource Name | Function & Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| NHANES (WWEIA) [20] | Provides nationally representative data on food and nutrient consumption in the U.S. population. | Uses 24-hour dietary recall (gold standard); includes demographic, examination, and laboratory data. |

| FNDDS [20] | Provides the energy and nutrient values for foods and beverages reported in WWEIA, NHANES. | Contains data for energy and 64 nutrients for ~7,000 foods and beverages. |

| FPED [20] | Converts FNDDS foods into USDA Food Pattern components (e.g., fruits, vegetables, whole grains). | Allows researchers to assess adherence to dietary guideline recommendations. |

| Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) Database [3] | Provides measured data on total energy expenditure, used to validate equations for estimating energy requirements. | Considered a gold standard for measuring energy expenditure at the population level. |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the decision pathway for selecting and implementing an appropriate energy adjustment model.

Diagram 1: Model Selection Workflow for Energy Adjustment

The following diagram outlines the steps for a robust analysis plan, from data collection to interpretation, emphasizing energy adjustment.

Diagram 2: Experimental Analysis Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the core challenge when adapting an RCT-like question to a cohort study in nutritional research?

The core challenge is reconciling the investigator-controlled intervention of an RCT with the observational nature of a cohort study. In an RCT, participants are randomly assigned to an intervention (e.g., a specific diet), which balances both known and unknown confounding factors across groups [34]. In a cohort study, researchers observe a naturally occurring exposure (e.g., habitual dietary intake) without any intervention [35] [34]. The primary methodological adaptation lies in using sophisticated statistical models to isolate the effect of a specific dietary component from the overall diet and other confounding factors, thereby approximating the causal question an RCT would ask [36] [2].

Q2: Why is adjusting for total energy intake so critical in observational studies of diet and disease?

Adjusting for total energy intake is fundamental for several reasons [37]:

- To Control for Confounding: Energy intake is correlated with physical activity, body size, and metabolic efficiency, which are themselves related to disease risk. Without adjustment, an association between a nutrient and a disease could be non-causal and merely reflect this shared link with total energy.

- To Reduce Extraneous Variation: Variation in nutrient intake resulting from differences in overall energy intake that are unrelated to disease risk can weaken true associations.

- To Model Realistic Interventions: Individuals changing their diet typically alter its composition without drastically changing their total energy intake (unless also changing physical activity or body weight). Energy adjustment helps predict the effect of such compositional changes [37].

Q3: What do the different energy adjustment models actually estimate?

Different models answer different research questions, which is a common source of confusion [2].

Table 1: Common Energy Adjustment Models and Their Interpretations

| Model Name | Statistical Approach | Target Estimand (What it Estimates) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard/Residual Model | Adjusts for total energy intake | Average Relative Causal Effect | The effect of substituting the exposure nutrient for a weighted average of all other energy sources [2]. |

| Energy Partition Model | Adjusts for energy from all other sources | Total Causal Effect | The effect of adding the exposure nutrient to the diet, keeping all else constant [2]. |

| Nutrient Density Model | Uses nutrient intake as a proportion of total energy | Rescaled Relative Effect | Attempts to estimate the relative causal effect, rescaled as a proportion of total energy; interpretation can be obscure [2]. |

| All-Components Model | Simultaneously adjusts for all other dietary components | Unconfounded Total or Relative Effect | Provides a less biased estimate of either effect by fully accounting for the diet's composition [2]. |

Q4: How can I implement a substitution analysis in a cohort study to mimic an RCT?

The "leave-one-out" method is a powerful approach for modeling isocaloric substitutions. This method mimics an RCT where one group receives calories from one source, and another group receives the same calories from a different source, with all else held constant [36].

For example, to model the substitution of SFA with PUFA, a Cox regression model would be specified as [36]:

Log(h(t; x)) = log(h0(t)) + β1PUFA + β2MUFA + β3Carbohydrates + β4Protein + β5Alcohol + β6Totalenergyintake + β7Confounders

In this model, the hazard ratio for β1 represents the estimated effect of replacing a specific amount of energy from SFA with an equivalent amount from PUFA.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Misinterpretation of Model Estimates

- Problem: A researcher observes a null or counterintuitive association between a nutrient and a health outcome but has not considered the implicit question their model is asking.

- Solution:

- Clearly define your research question: Are you asking about adding a nutrient to the diet (a total effect) or replacing one nutrient with another (a substitution effect)?

- Select the statistical model that matches this question (refer to Table 1).

- For substitution effects, use the leave-one-out or all-components model to ensure the model is isocaloric and correctly specified [36] [2].

Issue 2: Dealing with Dietary Confounding and Collider Bias

- Problem: Energy intake is a collider variable, as it is a consequence of all individual nutrient intakes. Conditioning on it (by adjusting for it) can create spurious associations between the nutrients if they also share other common causes [2].

- Solution:

- The most robust method is to use the "all-components model", which includes all major dietary components (protein, fat, carbohydrates, etc.) in the same model. This provides a less biased estimate than adjusting for a summary variable like total energy or remaining energy [2].

- Be transparent about the limitations of your data and the potential for residual confounding.

Issue 3: Addressing Misreporting of Energy Intake

- Problem: Self-reported dietary data from tools like Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs) or dietary records are prone to systematic under- or over-reporting, which can severely bias results [38] [3].

- Solution:

- Internal Validation: If resources allow, use objective biomarkers like doubly labeled water (DLW) to measure total energy expenditure in a subset of the cohort to calibrate the self-reported intake data [38] [3].

- External Calibration: Use existing predictive equations and anthropometric data (body weight, height) to estimate energy intake required to sustain observed body weight and physical activity levels. This can serve as a complementary measure to assess and correct for misreporting in your primary data [3].

- Sensitivity Analyses: Conduct analyses excluding participants identified as extreme misreporters (e.g., those with implausible energy intake values) [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Methodological Components for Dietary Adaptation Studies

| Item / Method | Function & Role in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Cohort Study with Dietary Data | Provides the foundational observational data. Requires detailed, prospectively collected dietary intake information, often via FFQs or dietary records [35]. |

| "Leave-One-Out" Model | The core statistical engine for performing isocaloric substitution analysis, allowing the investigator to model the effect of replacing one food or nutrient with another [36]. |

| All-Components Model | A more robust statistical approach that adjusts for all other dietary components simultaneously to minimize residual confounding from the overall diet composition [2]. |

| Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) | The gold-standard biomarker for total energy expenditure. Used to validate and calibrate self-reported energy intake data, addressing misreporting bias [38] [3]. |

| FADS1 Genotyping | An example of a tool for personalized nutrition research. Genetic variation (e.g., in the rs174550 SNP) can modify the association between fatty acid intake and health outcomes, allowing for stratified analyses [36]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Substitution Analysis

Aim: To estimate the effect of isocalorically replacing 5% of energy from Saturated Fatty Acids (SFA) with Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFA) on all-cause mortality in a large prospective cohort.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Cohort Definition: Identify your study population from a prospective cohort study (e.g., the ULSAM cohort) [36]. Exclude participants with prevalent disease at baseline and those with implausible energy intake reports.

- Exposure Assessment: Use baseline dietary intake data collected from a validated 7-day dietary record or a detailed FFQ. Compute daily intakes of all nutrients and foods.

- Model Specification: Use a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model. The model should be specified using the leave-one-out principle [36]:

Log(h(t; x)) = log(h0(t)) + β1PUFA + β2MUFA + β3Carbohydrates + β4Protein + β5Alcohol + β6Totalenergyintake + β7Confounders- Where all nutrients are expressed in units of 100 kcal.