Strategies to Improve Adherence to Dietary Weight Loss Interventions: A Research and Clinical Perspective

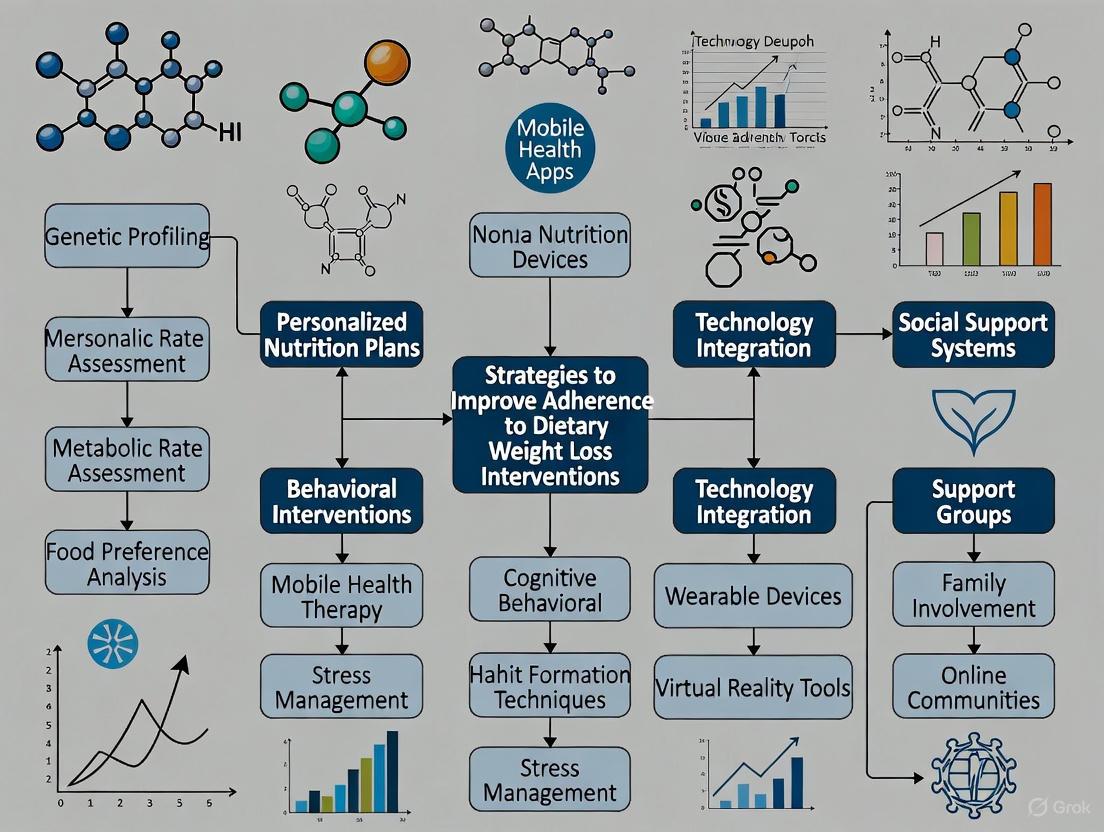

This article synthesizes current evidence and future directions for improving adherence in dietary weight loss interventions, a critical determinant of long-term success beyond specific macronutrient composition.

Strategies to Improve Adherence to Dietary Weight Loss Interventions: A Research and Clinical Perspective

Abstract

This article synthesizes current evidence and future directions for improving adherence in dietary weight loss interventions, a critical determinant of long-term success beyond specific macronutrient composition. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational evidence linking adherence to outcomes, methodological applications of behavioral and pharmacological strategies, troubleshooting for non-response and engagement decline, and validation through comparative efficacy studies. The scope encompasses behavioral techniques like self-monitoring and social support, emerging digital health technologies, and the integration of novel pharmacotherapies with lifestyle intervention, providing a comprehensive framework for enhancing the efficacy and sustainability of obesity treatments.

The Critical Link Between Dietary Adherence and Weight Loss Success

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the difference between adherence to a diet's composition and adherence to the behavior of self-monitoring? Adherence has two key components in weight loss research. The first is adherence to the prescribed dietary strategy (e.g., macronutrient goals). The second is adherence to the behavioral practices of the intervention, such as self-monitoring (e.g., recording food intake) [1] [2]. Research indicates that the combination of both high adherence to the diet and high adherence to self-monitoring is significantly more effective for weight loss than either factor alone [2].

2. Why do participants struggle to adhere to dietary interventions over time? Adherence declines due to several factors, including the increased drive to eat that accompanies energy restriction, the perceived burden of self-monitoring (especially dietary recording), and intervention fatigue [1] [3]. In digital interventions, challenges also include the timing and relevance of feedback messages, and a decline in engagement with digital tools [1] [4].

3. What are the most effective strategies to improve adherence? Evidence points to several key strategies:

- Supervision and Support: Interventions with supervised attendance and social support have significantly higher adherence rates than those without [5].

- Tailored Feedback: Providing personalized feedback on self-monitoring data can help sustain engagement, though its delivery must be optimized [1] [4].

- Dietary Focus: Programs focusing on dietary modification have shown better adherence than those focusing exclusively on exercise [5].

- Reducing Drive to Eat: Designing diets that help control hunger, such as those that induce ketosis, can improve adherence by addressing a key physical barrier [3].

4. How is adherence quantitatively measured in clinical trials? Adherence is measured using multiple metrics. The table below summarizes common methods and benchmarks based on clinical research:

Table 1: Quantitative Measures of Adherence in Dietary Weight Loss Trials

| Adherence Component | Measurement Method | Example Metric / Benchmark |

|---|---|---|

| Self-Monitoring of Diet | Digital food logs [1] | Recording ≥50% of daily calorie goals for ≥15 days/month [1] |

| Self-Monitoring of Weight | Smart scale data transmission [1] | Percentage of days with weight data recorded [1] |

| Self-Monitoring of Activity | Wearable device data [1] | Recording ≥500 steps per day [1] |

| Adherence to Diet Type | 24-hour dietary recalls [2] | Change in target macronutrient intake (e.g., net carbs for low-carb diets) [2] |

| Adherence to Diet Quality | Healthy Eating Index (HEI) scores [2] | An above-median improvement in HEI score [2] |

| Program Completion | Study retention data [5] | Overall adherence rate (meta-analysis average: 60.5%) [5] |

5. What are common pitfalls in designing adherence protocols, and how can they be avoided? Common pitfalls include high participant attrition, poor compliance with dietary requirements, and failure to maintain blinding [6] [7]. These can be mitigated by:

- Implementing a run-in period to assess participant motivation [6].

- Maintaining regular contact with participants, especially during control phases [6].

- Providing flexibility within the dietary requirements to accommodate preferences, potentially using herbs and spices to maintain acceptability [8].

- Using digital tools to reduce the burden of self-monitoring [1] [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Challenge: Declining Self-Monitoring Engagement Over Time

Problem: Participants initially engage with self-monitoring tools (diet apps, wearables) but adherence drops significantly after the first few weeks or months [1] [4].

Investigation & Resolution:

- Step 1: Diagnose the Cause. Determine if the drop is due to burden, lack of feedback, or technical issues.

- Check: Analyze engagement data to see if the decline is correlated with a specific intervention phase or tool.

- Example: In the SMARTER trial, adherence to self-monitoring declined non-linearly over 12 months, but feedback helped slow the decline [1].

- Step 2: Optimize Feedback. Ensure feedback is timely, relevant, and non-generic.

- Protocol: Use a system like the SMARTER app, which delivered up to three tailored messages daily based on available self-monitoring data. Message libraries should be refreshed regularly to avoid desensitization [1].

- Step 3: Reduce Burden. Explore simplified self-monitoring methods.

- Protocol: As in the Spark trial, consider testing the necessity of multiple self-monitoring components (diet, steps, weight) to identify the minimal effective "package" that minimizes participant burden while maintaining efficacy [9].

Challenge: Poor Adherence to Prescribed Macronutrient Goals

Problem: Participants are not meeting their targets for calorie, carbohydrate, or fat intake, despite reporting compliance.

Investigation & Resolution:

- Step 1: Verify Data Quality. Assess the accuracy of dietary intake data.

- Step 2: Emphasize Diet Quality alongside Composition. Focus on food quality, not just macros.

- Protocol: As in the DIETFITS trial, categorize participants not just by adherence to low-carb or low-fat goals, but also by their improvement in Healthy Eating Index (HEI) scores. The greatest weight loss success was seen in the "High Quality/High Adherence" subgroups [2].

- Step 3: Incorporate Dietary Preferences. Tailor the diet to individual likes and cultural habits.

- Protocol: During the intervention design, develop culturally appropriate recipes that incorporate herbs and spices to maintain palatability and acceptability of healthier food options [8]. This improves long-term sustainability.

Challenge: High Attrition Rates in Long-Term Trials

Problem: A large percentage of participants drop out before the study concludes, threatening the validity of the results [6].

Investigation & Resolution:

- Step 1: Analyze Reasons for Dropout. Systematically collect data on why participants leave.

- Check: As done in the dairy intervention trial [6], conduct interviews or surveys with participants who drop out. Common reasons include inability to comply with the diet, health problems, and excessive time commitment.

- Step 2: Implement Retention Strategies. Proactively address common barriers.

- Protocol: Based on trial feedback, key strategies include [6]:

- Offering monetary compensation for completion.

- Sending reminder letters and phone calls before appointments.

- Providing nutritional counseling to help participants overcome hurdles (e.g., weight gain during a high-dairy phase).

- Minimizing the time commitment and number of in-person visits where possible.

- Protocol: Based on trial feedback, key strategies include [6]:

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Testing the Efficacy of Feedback on Self-Monitoring Adherence

This protocol is based on the SMARTER mobile health weight-loss trial [1].

1. Objective: To compare adherence to self-monitoring and behavioral goals between participants receiving automated feedback (SM+FB) and those in a self-monitoring only (SM-only) arm over 12 months.

2. Materials: Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Digital Adherence Trials

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Fitbit App (or equivalent) | Allows participants to record food intake and view nutrient values and daily summaries. |

| Wrist-worn Activity Tracker | Automatically collects physical activity data (e.g., steps) and syncs with a smartphone. |

| Smart Scale | Transmits weight data directly to the study database, providing an objective adherence measure. |

| Tailored Feedback Algorithm | Generates and delivers personalized messages to participants based on their incoming self-monitoring data. |

| 24-Hour Dietary Recall | A validated method used to verify and supplement self-reported dietary intake data from apps. |

3. Methodology:

- Participants: Adults with a BMI typically between 27-43 kg/m².

- Initial Session: All participants receive a single, one-on-one session with a dietitian to set goals and learn to use the digital tools.

- Randomization: Participants are randomized to SM+FB or SM-only.

- Intervention:

- SM-only group: Instructed to self-monitor diet, activity, and weight daily using the provided tools.

- SM+FB group: Performs the same self-monitoring but also receives up to three tailored feedback messages per day via a custom app. Message content is based on their data (e.g., "Calorie intake is above your goal, while fat grams are right on target.").

- Data Collection: Adherence is calculated monthly as the percentage of days participants meet the criteria for diet, activity, and weight self-monitoring. Weight is measured objectively.

4. Analysis:

- Use generalized linear mixed models to compare adherence patterns between groups over time.

- Examine the association between adherence measures and achieving ≥5% weight loss.

The workflow and key decision points for implementing and optimizing a feedback intervention are summarized in the diagram below:

Protocol 2: Isolating Active Ingredients of Self-Monitoring Using a Factorial Design

This protocol is based on the Spark trial, which employs the Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST) [9].

1. Objective: To examine the unique and combined weight loss effects of three self-monitoring strategies (tracking dietary intake, steps, and body weight) in a 6-month digital intervention.

2. Methodology:

- Design: A 2x2x2 full factorial randomized trial. This creates 8 experimental conditions, as each self-monitoring component (diet, steps, weight) is either present or absent.

- Participants: Adults with overweight or obesity.

- Intervention:

- All participants receive core intervention components (weekly lessons, action plans).

- Participants are randomized to one of the eight conditions, determining which self-monitoring tools they receive (e.g., a mobile app for diet, a wearable for steps, a smart scale for weight).

- For each assigned strategy, participants are instructed to self-monitor daily and receive a corresponding goal and automated feedback.

- Data Collection: Weight is measured objectively via a smart scale at baseline, 1, 3, and 6 months. Engagement is tracked as the percentage of days each self-monitoring activity is performed.

3. Analysis:

- The primary aim is to test the main effects of each of the three self-monitoring components and their interactions on 6-month weight change.

- This design identifies which components are "active ingredients" and whether any combinations have synergistic or antagonistic effects.

The following diagram illustrates the factorial design and optimization process:

Evidence Establishing Adherence as a Primary Predictor of Outcomes

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is adherence considered a more critical factor than the specific type of dietary intervention for weight loss success? Multiple randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that the degree of adherence to a dietary protocol is a stronger predictor of weight loss success than the macronutrient composition of the diet itself. A study comparing popular diets (Atkins, Zone, Ornish, and Weight Watchers) found a strong correlation between self-reported adherence and weight loss, with no significant association between the type of diet and the amount of weight lost [3]. Subsequent analysis of the DIETFITS randomized clinical trial confirmed that the most significant weight loss occurred in participants who combined both high dietary quality and high adherence to their assigned macronutrient-limiting diet (either low-fat or low-carbohydrate) [2].

Q2: What are the primary methodological challenges in measuring adherence in nutritional research, and how can they be overcome? Randomized controlled trials in nutrition (RCTNs) face two unique challenges: the influence of the participant's background diet and the accurate assessment of adherence [10]. Unlike pharmaceutical trials, participants are inevitably exposed to food components similar to the intervention through their regular diet. Furthermore, reliance on self-reported data (e.g., pill-taking questionnaires, dietary recalls) often leads to misclassification and overestimation of adherence [10] [11]. Overcoming these challenges involves:

- Using Validated Nutritional Biomarkers: Objective biomarkers can quantify systemic exposure to a dietary compound, providing unbiased data on both background diet and adherence [10] [12].

- Employing Electronic Monitoring: Digital tools, such as smart packaging, provide passive, precise measurement of dosing events, eliminating the bias inherent in self-reporting [13] [14].

Q3: How does adherence impact long-term weight maintenance after initial loss? Adherence is a critical determinant of long-term weight maintenance. Research shows that poor adherence during an active weight loss phase is a primary indicator of subsequent weight regain. One study found that individuals with high adherence to a low-energy diet regained only 50% of the lost weight after two years, whereas those with low adherence regained nearly all (99%) of it [3]. This underscores that the compensatory increase in the drive to eat that accompanies weight loss can undermine adherence, making strategies to manage hunger essential for long-term success [3].

Q4: What strategies can improve adherence to digital self-monitoring in behavioral weight loss programs? Sustaining engagement with digital self-monitoring (SM) tools during the maintenance phase is challenging. Key strategies include [15]:

- Understanding Patterns: Engagement is typically highest for exercise tracking and lowest for dietary tracking. Disengagement often occurs around 6-8 months into the program.

- Tailored Support: Individual characteristics, such as high weight-related information avoidance, predict a faster decline in dietary SM. Interventions can use this information to provide targeted support to at-risk participants at critical time points.

- Leveraging Data Sharing: Providing health coaches with access to participants' digital SM data allows for proactive support and has been shown to improve adherence and mitigate weight regain.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inaccurate Adherence Measurement Skewing Trial Outcomes

Problem: Reliance on subjective adherence measures (e.g., self-reports, pill counts) is introducing bias and noise into outcome data, making it difficult to establish a true efficacy signal [11] [13].

Solution: Implement objective, passive measurement technologies.

Step 1: Select the appropriate digital adherence technology.

- For oral solids: Utilize smart packaging like pill bottles or blister packs with integrated microchips that record the date and time of opening [13] [14].

- For other formulations: Explore digital solutions for injectables, inhalers, and creams that timestamp the activation event [14].

- For direct ingestion confirmation (Phase I): Consider "smart pills" with ingestible sensors, though scalability may be limited [13].

Step 2: Integrate the technology into the clinical supply chain. Work with a partner offering pre-qualified solutions to avoid lengthy vendor qualification processes, which can take 6-9 months [14].

Step 3: Utilize the rich dosing history data. Analyze the timestamp data to identify patterns of non-adherence (e.g., drug holidays, weekend skipping) and implement timely interventions. This data provides a causal pathway between medication intake, drug exposure, and treatment effects [13].

Issue 2: High Participant Drop-off and Non-Adherence in Long-Term Studies

Problem: Participant adherence decreases significantly over time, particularly in long-term trials, leading to loss of statistical power and potentially failed studies [16] [15] [14].

Solution: Proactively manage adherence through study design and participant engagement.

Step 1: Design the diet to control the physiological drive to eat. Consider dietary interventions that help manage hunger, such as ketogenic diets or very low-energy diets (VLEDs), which are associated with higher adherence and rapid, motivating weight loss [3].

Step 2: Tailor interventions to individual preferences. While ensuring nutritional adequacy, personalize dietary recommendations to a participant's food preferences to enhance long-term sustainability [3].

Step 3: Implement a data-driven feedback loop. Use data from digital adherence tools to:

- Provide participants with feedback on their adherence behavior to foster engagement [13].

- Enable investigators to monitor patterns, identify at-risk participants, and provide proactive, tailored support [13] [15].

- Allow sponsors to evaluate the impact of adherence on study outcomes in real-time [13].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Key Methodologies from Cited Adherence Studies

| Study Focus | Adherence Measurement Method | Primary Outcome | Key Finding on Adherence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bariatric Surgery (OBSERVE Study) [16] | Dietary Behavior Inventory-Surgery (DBI-S) questionnaire at multiple timepoints. | Percentage Total Weight Loss (%TWL) at 24 months. | A positive causal influence of dietary adherence on %TWL is hypothesized (Study ongoing, results pending). |

| Cocoa Flavanol RCT (COSMOS) [10] | Validated urinary biomarkers (gVLMB & SREMB). | Cardiovascular disease (CVD) events and mortality. | Biomarker-based analysis revealed 33% non-adherence (vs. 15% by self-report) and showed stronger treatment effects (e.g., Major CVD events HR: 0.48). |

| Medication Adherence (ARBITER 2) [11] | Pill count vs. 24-hour recall vs. refill history. | Adherence percentage to statin therapy. | Pill counts revealed significantly lower adherence (78.7%) than simpler methods and were sensitive to temporal changes. |

| Pediatric Multidisciplinary Program [17] | Adherence to lifestyle recommendations via questionnaire. | Change in BMI classification and Δ30BMI. | Adherence to breakfast recommendations was a significant predictor of moving to a lower weight class (aOR: 1.60). |

| Digital Self-Monitoring [15] | Days per month of tracking via digital tools. | Patterns of engagement during weight loss maintenance. | Only 21% of participants maintained high dietary self-monitoring; disengagement typically occurred at 7-8 months. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Adherence Measurement

| Solution / Tool | Function / Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Nutritional Biomarkers (e.g., gVLMB, SREMB) [10] | Objective, quantitative biomarkers in biofluids (e.g., urine, plasma) that measure systemic exposure to a specific nutrient or food compound. | RCTs targeting specific bioactive dietary components (e.g., flavanols, carotenoids). Corrects for background diet and misreported intake. |

| Dietary Guideline Index for Children & Adolescents (DGI-CA) [12] | A validated index score based on adherence to national dietary guidelines, assessing core food groups and discretionary foods. | Observational and intervention studies aiming to link overall diet quality with health outcomes in pediatric populations. |

| Electronic Monitoring Devices (e.g., MEMS Cap) [13] | Drug packaging (bottles, blisters) with microchips that passively record the date and time of opening. | Clinical trials (pharmaceutical and nutritional) where precise timing and patterns of supplement/medication intake are critical. |

| Smart Packaging Portfolio [14] | A suite of pre-qualified, digital packaging solutions for various formats (bottles, injectables, inhalers) that passively record dosing events. | Integrated into clinical supply chains to ensure GMP/GCP compliance and provide reliable adherence data without burdening the patient. |

| Digital Self-Monitoring Platforms [15] | Mobile apps and connected devices (e.g., digital scales, activity trackers) for tracking weight, diet, and exercise. | Behavioral weight loss interventions. Facilitates real-time monitoring and can be used to drive remote coaching interventions. |

Visualized Workflows and Pathways

Dietary Adherence Research Workflow

Impact of Adherence on Trial Outcomes

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary biological mechanisms driving increased appetite during energy restriction? The increased drive to eat is largely mediated by hormonal changes that convey energy status to the brain. A key mechanism is the significant and often disproportionate reduction in circulating leptin, a hormone secreted by adipocytes in proportion to fat mass [18]. This decline in leptin promotes increased motivation to eat via down-regulation of anorexigenic neuropeptides (e.g., POMC, α-MSH) and up-regulation of orexigenic neuropeptides (e.g., NPY, AgRP) in the hypothalamus [18]. This system appears to be asymmetrical, with a much stronger defense against energy deficit than against overconsumption [18] [19].

FAQ 2: Is the counter-regulatory drive universal across different types of dietary interventions? While a heightened drive to eat is a common physiological response to energy deficit, its intensity can be influenced by the dietary strategy. Some evidence suggests that ketogenic diets, including those using Very Low Energy Diets (VLEDs), may help control the increased drive to eat, potentially due to the appetite-suppressing effects of ketosis [20]. Furthermore, emerging research indicates that the timing of energy intake, such as early time-restricted eating (eTRE), may offer additional benefits for improving metabolic outcomes compared to energy restriction alone, though its direct impact on the drive to eat requires further study [21].

FAQ 3: How can we accurately monitor and account for this biological response in clinical trials? Self-monitoring (SM) of diet, physical activity, and weight is a cornerstone behavioral strategy for assessing adherence. The use of digital tools (e.g., smartphone apps, wearable devices, smart scales) can reduce the burden of monitoring [1]. Research shows that higher adherence to self-monitoring is significantly associated with greater odds of achieving clinically meaningful weight loss (e.g., ≥5%) [1]. Accurately quantifying energy intake is complex; mathematical models that calculate metabolized energy intake using doubly labelled water and changes in body energy stores from Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA) can provide objective measures of adherence and help explain deviations from expected weight loss [20].

FAQ 4: What are the common pitfalls in trial design that fail to account for this biological drive? Common pitfalls include a lack of strategies to manage increased hunger, overly rigid dietary protocols that do not accommodate individual preferences, and insufficient monitoring of adherence. Trials that do not incorporate a run-in period to assess participant motivation and compliance potential, or that fail to maintain regular contact—especially during control phases—are at higher risk for attrition and poor adherence [6]. Providing flexibility within dietary requirements and ensuring the dietary intervention is acceptable and palatable to participants are key considerations for improving compliance [8] [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Attrition and Poor Dietary Adherence in Long-Term Interventions

| Potential Cause | Underlying Mechanism | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unmanaged Hunger | Physiological increase in orexigenic drive due to leptin decline and other hormonal cues [18]. | Consider dietary designs that help control hunger, such as ketogenic diets or VLEDs, which are associated with higher adherence and rapid, motivating weight loss [20]. |

| Dietary Inflexibility | Intervention conflicts with personal, cultural, or traditional food preferences, reducing acceptability [8]. | Tailor interventions to individual dietary preferences while meeting nutritional goals. Use herbs and spices to maintain palatability of healthier foods [20] [8]. |

| Burden of Self-Monitoring | Participant fatigue from manually and frequently recording food intake and other behaviors [1]. | Implement mHealth tools (apps, wearables, smart scales) to automate data collection and reduce participant burden [1]. |

| Insufficient Support | Lack of feedback or guidance, leading to loss of motivation and engagement [1] [6]. | Integrate regular, tailored feedback. Note: One study found remote feedback alone was insufficient for some; message content, timing, and relevance are critical [1]. |

Problem: Inaccurate Reporting of Energy Intake Blurring Intervention Efficacy

| Challenge | Solution | Experimental Protocol / Tool |

|---|---|---|

| Fluctuating Daily Intake | Poor adherence creates a gap between prescribed and actual energy intake, leading to a weight loss plateau [20]. | Use mathematical modeling of energy intake based on energy expenditure (from doubly labelled water) and change in energy stores (from DEXA) [20]. |

| Under-Reporting in Food Diaries | Self-reported data is often incomplete or inaccurate. | Combine self-report with objective biomarkers. In a provided-food study, quantify adherence by comparing provided food to calculated actual intake [20]. |

| Lack of Real-Time Data | Researchers cannot identify adherence issues as they occur. | Utilize a digital health infrastructure where participants use a designated app (e.g., Fitbit) and smart scale for real-time or daily monitoring of diet, activity, and weight [1]. |

Key Signaling Pathways in Appetite Regulation

The following diagram illustrates the core hypothalamic pathway through which energy restriction and falling leptin levels increase the drive to eat.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Quantifying Adherence and Energy Intake in a Dietary Intervention

Objective: To objectively measure adherence to a prescribed diet and calculate actual metabolized energy intake in a weight loss trial [20].

Methodology:

- Participant Screening: Recruit overweight/obese adults. Exclude for conditions affecting energy balance (e.g., diabetes, use of weight-loss medications) [6].

- Baseline Assessment:

- Measure body composition via Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA).

- Measure total energy expenditure (TEE) over 7-14 days using the doubly labelled water (DLW) method.

- Intervention Phase:

- Provide all food to participants to control for dietary composition and prescribed energy intake.

- Instruct participants to maintain their usual physical activity levels.

- Adherence Monitoring:

- Endpoint Assessment (Post-Intervention):

- Repeat DEXA and DLW measurements.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate Metabolized Energy Intake: Average energy intake over the intervention is calculated as: Energy Intake = TEE (from DLW) + Change in Body Energy Stores (from DEXA).

- Classify Adherence: Compare the calculated energy intake to the prescribed energy intake from provided food. Participants can be stratified into tertiles (e.g., high, medium, low adherers) based on this comparison [20].

Protocol 2: Testing a Feedback Intervention to Improve Self-Monitoring Adherence

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of a mobile health (mHealth) feedback system in improving adherence to self-monitoring and behavioral goals over 12 months [1].

Methodology:

- Design: A two-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT).

- Participants: Adults with a BMI between 27-43 kg/m².

- Initial Session: All participants receive a single 90-minute, one-on-one session with a dietitian to set behavioral goals (calorie, fat, physical activity minutes) and receive training on digital self-monitoring tools [1].

- Digital Tool Provision:

- Diet: Smartphone app (e.g., Fitbit) for logging food intake.

- Physical Activity: Wrist-worn activity tracker (e.g., Fitbit Charge).

- Weight: Smart scale that transmits data daily.

- Intervention Arms:

- SM-Only Group: Self-monitors using the digital tools.

- SM+FB Group: Self-monitors and receives up to three tailored feedback messages per day via a custom app. Messages address diet, activity, and weekly weighing, and are based on uploaded self-monitoring data [1].

- Outcome Measures:

- Primary: Percent weight loss from baseline to 12 months.

- Secondary (Adherence):

- Diet SM Adherence: Percentage of days with ≥50% of daily calorie goal recorded.

- PA SM Adherence: Percentage of days with ≥500 steps recorded.

- Weight SM Adherence: Percentage of days with a weight measurement.

- Goal Adherence: Percentage of days meeting calorie, fat, and physical activity goals [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Function in Experimental Context |

|---|---|

| Doubly Labelled Water (DLW) | Gold-standard method for measuring total energy expenditure in free-living individuals over 1-2 weeks. Essential for calculating objective energy intake [20]. |

| Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA) | Precisely quantifies body composition (fat mass, fat-free mass). Used with DLW to calculate changes in body energy stores for determining metabolized energy intake [20]. |

| Leptin ELISA Kits | To quantify circulating leptin concentrations in serum/plasma as a biomarker of adipose-derived energy storage signals and to confirm the hormonal state of energy deficit [18]. |

| Validated Visual Analog Scales (VAS) | Subjectively measure components of appetite (hunger, desire to eat, fullness, prospective consumption) at specific timepoints to correlate with physiological measures [19]. |

| mHealth Digital Suite | Integrated system of apps, wearable activity trackers, and smart scales to facilitate low-burden, high-frequency self-monitoring and enable real-time data collection and feedback delivery [1]. |

| Standardized Food Provision | Providing all or key study foods to participants ensures strict control over dietary composition and energy intake, removing variability from self-selection and preparation [20]. |

Data Presentation: Key Quantitative Findings

Table 1: Impact of Dietary Adherence on Weight Loss Outcomes

| Study Design / Metric | High Adherers | Low Adherers | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Energy Diet (LED) [20] | |||

| Average Energy Intake (kcal/day) | 644 ± 74 | 1573 ± 33 | < 0.001 |

| Rate of Weight Loss (g/day) | 126.5 ± 7.7 | 56.9 ± 2.7 | < 0.001 |

| mHealth Self-Monitoring [1] | |||

| Association with ≥5% Weight Loss (Odds) | Significantly Greater Odds | Significantly Lower Odds | < 0.05 |

| Outcome Measure | eTRE + ER Group | lTRE + ER Group | ER Alone Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body Mass Loss (kg) | -5.0 (-5.7, -4.3) | -4.4 (-5.2, -3.6) | -4.3 (-5.0, -3.6) |

| Fat Mass (%) | -1.2*† | -0.0* | -0.1† |

| Fasting Glucose (mmol/L) | -0.35* | -0.00* | -0.18 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | -4* | -1 | -0 |

Values with the same symbol (, †) within a row are significantly different from each other.

Ketogenic Diets as a Strategy to Modulate Appetite and Physiology

For researchers investigating strategies to improve adherence to dietary weight loss interventions, the ketogenic diet (KD) presents a fascinating case study. This high-fat, very-low-carbohydrate diet aims to shift the body's metabolism into a state of nutritional ketosis, where fat-derived ketone bodies become the primary fuel source, replacing glucose [22]. This shift is associated with several physiological changes, including appetite modulation, which can influence dietary adherence. This technical support center provides an overview of the mechanisms, key experimental methodologies, and common research challenges related to studying the KD's effects on appetite and physiology.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the core physiological mechanisms by which a ketogenic diet modulates appetite?

The KD influences appetite through multiple, interconnected hormonal and metabolic pathways. The primary mechanisms identified in the literature are summarized below.

- Table: Appetite Modulation Mechanisms of the Ketogenic Diet

| Mechanism | Physiological Basis | Key Biomarkers / Mediators |

|---|---|---|

| Hormonal Shifts | Increased satiety hormone release and altered hunger signaling [23] [24]. | ↑ Cholecystokinin (CCK), ↑ Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1); potential modulation of ghrelin [24]. |

| Ketone Body Effects | Direct appetite-suppressive effects of ketone bodies [24]. | Elevated Beta-Hydroxybutyrate (BHB). |

| Reduced Lipogenesis | Decreased fat storage creation and increased fat breakdown [25] [24]. | Lowered insulin levels promoting lipolysis. |

| Stable Glycaemia | Avoidance of blood glucose and insulin spikes, reducing hunger sensations [23]. | Lower glycemic variability, improved insulin sensitivity [23]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the KD, these physiological mechanisms, and the resulting appetite modulation.

What are the most significant challenges to adherence in ketogenic diet trials, and what mitigation strategies are effective?

Adherence is a critical, and often limiting, factor in KD research. Common challenges and potential solutions are detailed below.

- Table: Adherence Challenges and Mitigation Strategies in KD Research

| Challenge | Impact on Adherence | Evidence-Based Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary Restrictiveness | High dropout rates; difficulty maintaining macronutrient targets [25] [26]. | Provide structured meal plans, recipes, and pantry guides [27]. Use modified KD approaches (e.g., Modified Atkins) with slightly more flexibility [24]. |

| Social & Dining Difficulties | Reduced quality of life; non-compliance in social settings [26]. | Incorporate behavioral counseling. Involve participants' family members in education sessions [27]. |

| "Keto Flu" & Side Effects | Early attrition during the adaptation period (1-2 weeks). | Forewarn participants. Ensure adequate electrolyte and fluid intake from the start. |

| Nutrient Quality Concerns | Long-term sustainability; potential for micronutrient deficiencies. | Emphasize a "well-formulated" KD with diverse, nutrient-dense whole foods and minimal dairy, if appropriate for the study design [27]. |

| Macronutrient Drift | Participants often consume more carbohydrates and less fat than the protocol requires, breaking ketosis [25]. | Implement frequent 24-hour dietary recalls or use a dedicated food-tracking mobile app (e.g., MyFitnessPal) with researcher monitoring [25] [27]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Core Protocol for a 12-Week Ketogenic Diet Intervention

This protocol is adapted from recent feasibility studies in clinical populations and can be tailored for research on adherence [27].

- Primary Objective: To assess the feasibility, adherence, and physiological effects of a 12-week ketogenic diet intervention in adults with overweight or obesity.

- Participant Selection:

- Inclusion Criteria: Adults (age ≥18 years), BMI ≥25 kg/m², stable weight for 3 months prior.

- Exclusion Criteria: Significant heart disease, diabetes, kidney stones, gallstones, or pregnancy [27].

- Dietary Intervention:

- Macronutrient Goals: 70-80% of daily energy from fat, 15-20% from protein, 5-10% from carbohydrates (typically <50 g/day) [23] [27].

- Diet Composition: Focus on whole foods. The diet can be modified to limit dairy products, as high dairy intake has been associated with risks for certain conditions, potentially improving the diet's safety profile and acceptability [27].

- Support Structure: Weekly group or individual sessions for the first month, bi-weekly thereafter. Sessions include nutritional education, cooking guidance, and troubleshooting [27].

- Adherence Monitoring:

- Ketone Bodies: Measure capillary or serum Beta-Hydroxybutyrate (BHB) weekly. A level of 0.5 - 3.0 mM is typically indicative of nutritional ketosis [25] [27].

- Dietary Intake: Use a combination of 3-day weighed food records and a dedicated phone app for real-time tracking [25] [27].

- Participant Feedback: Conduct qualitative interviews or use structured questionnaires to assess acceptability and barriers [27].

The workflow for implementing and monitoring this protocol is outlined below.

Key Signaling Pathways for Investigation

The neurobiological pathways underlying appetite regulation on a KD are complex. Two key pathways for experimental investigation are:

Pathway 1: Gut-Brain Axis Signaling

- Mechanism: KD-induced changes in gut microbiome composition and subsequent production of microbial metabolites (e.g., short-chain fatty acids) can influence central appetite regulation via the vagus nerve [24].

- Experimental Measurement: 16S rRNA sequencing of fecal samples to assess microbiome changes; serum metabolomics for SCFA levels; functional MRI to assess brain activity in response to food cues.

Pathway 2: Central Nervous System (CNS) Neurotransmitter Balance

- Mechanism: Ketone bodies, particularly BHB, may increase central nervous system levels of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA and modulate glutamate receptors, leading to stabilized neural networks and potential appetite suppression [22] [24].

- Experimental Measurement: Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) to measure GABA and glutamate levels in the brain; assessment of behavioral correlates of appetite.

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section details essential reagents, assays, and equipment for conducting rigorous research on the ketogenic diet.

- Table: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Application | Example Protocol / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Beta-Hydroxybutyrate (BHB) Assay | Primary objective biomarker for verifying nutritional ketosis [25] [27]. | Use handheld ketone meters for capillary blood (frequent monitoring) or serum assays via ELISA/colorimetric kits for higher precision in lab settings. |

| Food Tracking Software | To quantify adherence to macronutrient targets and energy intake [25]. | Utilize apps like MyFitnessPal. Researchers should train participants and export data for analysis. 24-hour dietary recalls can supplement this data. |

| Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA) | To precisely measure changes in body composition (fat mass, lean mass, bone mass) [28]. | Perform scans at baseline and study endpoint. Critical for confirming that weight loss is primarily from fat mass, not muscle [28]. |

| Gut Microbiome Profiling Kits | To investigate the role of the gut-brain axis in appetite modulation [24]. | Collect fecal samples at baseline and endpoint. Use 16S rRNA gene sequencing or shotgun metagenomics for taxonomic and functional analysis. |

| Hormone Panels | To measure changes in appetite-related hormones [23] [24]. | Use multiplex ELISA or Luminex assays to profile GLP-1, CCK, ghrelin, leptin, etc., from fasting plasma samples. |

| Indirect Calorimetry | To measure resting energy expenditure and respiratory quotient (RQ), confirming a metabolic shift toward fat oxidation (lower RQ) [23]. | Conduct measurements in a fasted state under standardized conditions. A decreased RQ confirms increased fat utilization. |

Evidence-Based and Emerging Methodologies to Enhance Adherence

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common technical challenges researchers may encounter when implementing digital self-monitoring tools in dietary weight loss interventions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the optimal frequency of dietary self-monitoring for weight loss maintenance? A: Evidence suggests that self-monitoring at least three days per week may be helpful for long-term weight loss maintenance, but greater benefit is observed when self-monitoring five to six days per week. Daily monitoring is not always necessary for effectiveness, which can reduce participant burden [29].

Q2: Why might participants fail to engage with digital self-monitoring tools despite receiving feedback? A: Remotely delivered feedback alone can be insufficient to sustain engagement. Ineffectiveness may occur due to poor timing of message delivery, lack of engagement with the digital tools, or if the message content is not perceived as relevant to the participant at that moment [1].

Q3: How does the timeliness of self-monitoring entry affect data quality? A: Timely recording is crucial. Research using instrumented paper diaries (IPDs) found that the percentage of weight lost correlated significantly not only with the frequency of self-monitoring but also with the number of diary entries made close to the time of eating. Delayed or batched recording can introduce recall bias and reduce the opportunity for participants to take corrective action during the day [30].

Q4: What are common technical barriers to adopting digital self-monitoring tools in clinical research? A: Users often experience a mismatch between system usability and their technical competencies. The choice to adopt and integrate these tools depends on the perceived balance between the added benefits and the effort required to achieve them. Common technical issues include problems with software installation, connectivity, and data synchronization [31] [32].

Troubleshooting Common Technical Problems

| Problem Category | Specific Issue | Suggested Solution for Research Staff |

|---|---|---|

| Access & Authentication | Participant forgets login credentials [32] [33]. | Implement a self-service password reset portal. If unavailable, guide participants through identity verification via email or security questions. |

| Software & Application | Application fails to run or crashes [32]. | Guide participants to check software compatibility with their device OS, restart the application, reinstall the program, or check for and install software updates. |

| Hardware & Connectivity | Slow device performance [32] [33]. | Instruct participants to close unnecessary background applications, free up disk space, and run antivirus or anti-malware scans. |

| Unrecognized USB device (e.g., smart scale) [32]. | Advise participants to restart their computer, try a different USB port, and check for and update device drivers on their computer. | |

| Slow or lost internet connection [32] [33]. | Have participants restart their router and modem, check Wi-Fi signal strength, and move closer to the router or use a wired connection for stability. |

Experimental Protocols and Quantitative Data

This section summarizes key methodologies and findings from recent studies on self-monitoring adherence.

| Study & Focus | Participant Group | Core Intervention & Methodology | Key Quantitative Finding on Adherence |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMARTER Trial (2025) [1] | 502 adults with obesity; 80% female, 82% White. | 12-month mHealth trial; compared self-monitoring (SM) only vs. SM + tailored feedback (FB) on diet, activity, and weight. | - Adherence to SM and behavioral goals declined nonlinearly over time.- The SM+FB group showed a less steep decline than the SM-only group.- Higher adherence to diet, PA, and weight SM was associated with greater odds of achieving ≥5% weight loss. |

| UF Frequency Study (2024) [29] | 75 adults with overweight or obesity. | 3-month internet-based weight loss program; explored various thresholds for dietary self-monitoring. | - 3-4 days/week of self-monitoring supported weight loss maintenance.- 5-6 days/week of self-monitoring supported additional weight loss. |

| PREFER/IPD Study [30] | Sub-sample from an 18-month behavioral weight-loss program. | Used Instrumented Paper Diaries (IPDs) to electronically validate the timing and frequency of self-monitoring. | - Self-reported diary usage significantly exceeded electronically documented usage.- Percentage of weight lost correlated significantly with the frequency of IPD use (p=.001) and timely entries (p=.002). |

Detailed Methodology: The SMARTER mHealth Trial Protocol

The SMARTER trial provides a robust example of a digital self-monitoring intervention [1].

- Participant Training: All participants received one 90-minute, one-on-one in-person session with a dietitian. This session covered behavioral strategies for weight reduction, goal setting, and instruction on using the digital self-monitoring tools.

- Dietary Self-Monitoring: Participants used the Fitbit app to record food intake. Calorie goals were individualized based on baseline body weight.

- Physical Activity Monitoring: Participants used a wrist-worn Fitbit Charge 2 device synced with their smartphone. The goal was to gradually increase activity to 150 minutes/week by 12 weeks, with an ultimate goal of 300 minutes/week by 52 weeks.

- Weight Monitoring: Participants were instructed to weigh themselves daily using a study-provided smart scale that transmitted data to the study database.

- Feedback Intervention (SM+FB Group Only): The intervention group received up to three tailored feedback messages per day via a custom app. Messages were based on available self-monitoring data and addressed caloric, fat, and added sugar intake daily, and physical activity every other day. The message library was refreshed monthly to prevent desensitization.

Visualizing the mHealth Trial Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of a digital self-monitoring intervention with feedback, as implemented in the SMARTER trial [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The table below details essential tools and methodologies used in modern self-monitoring research for dietary weight loss interventions.

| Item / Tool | Function in Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Instrumented Paper Diaries (IPDs) [30] | Objectively validates the timing and frequency of self-monitoring behaviors without participant awareness. | Critical for measuring true adherence and timeliness, overcoming the limitation of inflated self-reported data. |

| Digital Self-Monitoring Platform [1] [31] | Provides the infrastructure for participants to log diet, activity, and weight, and for researchers to collect and manage data. | Platforms like m-Path or commercial apps (e.g., Fitbit) are used. Ease of use is a major factor in participant adherence [31]. |

| Wearable Activity Tracker [1] | Automatically collects physical activity data (e.g., steps, active minutes), reducing participant burden. | Devices like the Fitbit Charge 2 can be synced with a study platform to provide objective PA data for analysis and feedback. |

| Smart Scale [1] | Transmits weight measurements wirelessly to a central database upon daily weighing. | Provides objective, frequent weight data without relying on participant self-report, enabling timely feedback. |

| Tailored Feedback Message Library [1] | A pre-written, dynamic set of messages used to provide automated, context-specific feedback to participants. | Message content, frequency, and timing must be carefully designed. The library should be refreshed periodically to maintain participant engagement. |

For researchers conducting dietary weight loss interventions, participant engagement with digital tools is a critical, yet often unstable, variable. Technical malfunctions and usability issues are not merely operational nuisances; they constitute significant sources of missing data and protocol deviations that can compromise study validity and power [1] [34]. Recent randomized controlled trials highlight that while higher adherence to self-monitoring via digital tools is associated with significantly greater odds of achieving ≥5% weight loss, maintaining this adherence is a persistent challenge [1] [35]. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting and methodologies to help research teams identify, mitigate, and preempt these technical barriers, thereby safeguarding data integrity and intervention efficacy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Research Teams

Q1: Our study participants are not receiving automated feedback messages. What could be the cause? A1: This is a common issue in mHealth trials. Based on recent studies, the causes can be multi-faceted [1] [34]:

- Message Delivery Failures: New FCC regulations (implemented March 2023) and carrier-level spam filters can automatically block legitimate study text messages, particularly those containing financial incentive information or high-frequency sends [34].

- Data Syncing Disruptions: Feedback algorithms often require recent self-monitoring data. If a participant's wearable (e.g., Fitbit) or smart scale has not synced data to the companion app, the system may lack the necessary information to trigger or tailor a message [1].

- Platform API Changes: In long-term studies, the discontinuation or update of application programming interfaces (APIs)—such as the MyFitnessPal-Fitbit integration—can sever data flow between devices and the central research platform, halting message delivery [34].

Q2: Why are we observing a steep, nonlinear decline in dietary self-monitoring adherence after the first few months? A2: The nonlinear decline in adherence is a well-documented pattern in digital weight loss trials. Research indicates this is rarely due to participant disinterest alone. Key technical and experiential factors include [1] [36]:

- User Interface Burden: Dietary logging remains a high-effort task. If the food database is difficult to search, barcode scanning is unreliable, or the app requires manual entry for complex meals, participant fatigue sets in.

- Lack of Perceived Relevance: Participants disengage if automated feedback messages are generic, ill-timed, or not perceived as personally relevant to their immediate challenges [1].

- Technical Friction: Frequent app crashes, slow loading times, and complex navigation menus directly lead to abandonment.

Q3: What are the most common points of failure in a system integrating wearables, smart scales, and an mHealth app? A3: The integrated system creates a chain that is only as strong as its weakest link. Common points of failure include [34] [37]:

- Device Pairing and Re-pairing: Bluetooth connections between wearables/apps and smartphones can be lost after operating system updates or app updates, requiring manual re-pairing.

- Scale Connectivity: "Smart" scales may fail to transmit data if Wi-Fi passwords are changed, the scale is moved to a new location with a weak signal, or its cellular data plan (for cellular models) expires [34].

- Data Sanitization: Raw data from consumer devices (e.g., step counts, active minutes) often requires cleaning and validation before it can be used for research purposes, a process prone to error [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Connectivity and Data Flow Issues

Problem: Weight data from smart scales is not appearing in the study database. Solution: Follow this systematic diagnostic protocol to isolate the point of failure.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Verify Scale Power & Setup: Confirm the scale has charged batteries or is plugged in. Ensure it is on a hard, level surface; carpets can interfere with sensors and connectivity.

- Check Local Connectivity: Have the participant open the companion app on their phone while standing near the scale. If the data is present in the app but not the research portal, the issue is with the app-to-portal API. If data is missing from the app, the scale-to-phone connection has failed.

- Confirm Data Transmission: For Wi-Fi scales, ensure the home network password hasn't changed. For cellular scales (e.g., BodyTrace), confirm the embedded cellular plan is active [34].

- Check Research Platform API: Review study platform logs for API errors from the scale manufacturer's server, which may indicate a system-wide issue requiring developer intervention [34].

Automated Feedback Message Failure

Problem: The intervention group is not receiving tailored feedback messages based on their self-monitoring data. Solution: Investigate the message generation and delivery pipeline.

Table: Components of Feedback Message Failure Analysis

| Component to Check | Diagnostic Method | Potential Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Data Availability | Check if recent, valid self-monitoring data exists in the database for the participant. | If no data, troubleshoot device syncing. If data exists, check algorithm logic. |

| Message Generation Algorithm | Review server-side logs for errors during message generation. Test algorithm with sample data. | Debug logic errors; ensure message library is correctly loaded and updated [1]. |

| Message Delivery Gateway | Check delivery status logs from SMS/email gateways. | Work with IT to register study numbers/mailers with carriers to avoid spam filtering [34]. |

| Participant Device | Confirm participants know how to view messages and that notifications are enabled. | Provide a simple guide for enabling app notifications on iOS and Android. |

Declining App Usability and Engagement

Problem: High initial usage followed by a rapid drop in app logins and feature use. Solution: Proactively assess and improve usability.

Protocol: Rapid Usability Assessment for Research Apps

- Method: Recruit a small sub-sample of participants (n=5-10) for a 20-minute structured interview and screen-sharing session.

- Tasks: Ask them to perform core tasks: log a meal, find a previous day's data, review a feedback message.

- Metrics: Measure effectiveness (task completion rate), efficiency (time on task), and satisfaction (post-task rating) [37].

- Analysis: Identify common points of friction (e.g., "too many clicks to log water," "can't find past weight graph"). The most frequently cited usability attributes to evaluate are outlined in the table below.

Table: Key Usability Attributes for mHealth Research Tools [37]

| Usability Attribute | Definition in Research Context | Evaluation Method |

|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction | The participant's perceived comfort and acceptability of using the app. | System Usability Scale (SUS); qualitative interviews. |

| Ease of Use | The degree to which the app can be used with minimal mental effort. | Task success rate; observation of user errors. |

| Perceived Usefulness | The participant's belief that the app will help them achieve their health goals. | Questionnaire; analysis of adherence correlates. |

| User Experience | The holistic experience of using the app, including emotional response. | Think-aloud protocols during task completion. |

| Effectiveness | The accuracy and completeness with which users achieve specified goals. | Data completeness metrics (e.g., % of days with diet logged). |

Experimental Protocols for Validating mHealth Tools

Before deploying a digital tool in a clinical trial, rigorous technical validation is required to ensure it functions as intended and is suitable for the target population.

Protocol: Technical Validation of Device Data Accuracy

Objective: To verify that data from consumer wearables and smart scales meets minimum accuracy thresholds for research purposes. Materials: Consumer device (e.g., Fitbit, Garmin), research-grade reference device (e.g., ActiGraph for activity, medical balance scale for weight), participant simulators (for controlled step testing). Methodology:

- Step Count Validation: Simultaneously mount the consumer wearable and reference device on a simulator or human participant. Program the simulator to execute a predefined series of steps (e.g., 1000 steps) at varying speeds. Record step counts from both devices [37].

- Weight Measurement Validation: Have a cohort of participants (n>30) weigh themselves sequentially on the smart scale and a calibrated medical scale. Record weights from both devices across a range of body masses.

- Data Analysis: Calculate intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) and mean absolute percentage errors (MAPE) between the consumer and research-grade devices. Establish a pre-defined acceptability threshold (e.g., ICC > 0.80, MAPE < 5% for steps).

Protocol: Piloting the End-to-End Data Pipeline

Objective: To ensure all components of the digital intervention—from device data capture to feedback message delivery—work cohesively before study launch. Materials: Full tech stack (devices, apps, central database, messaging system), pilot participants (n=10-15), data monitoring dashboard. Methodology:

- Scripted Scenario Testing: Pilot participants follow a scripted 3-day protocol of activities: daily self-weighing, food logging, and wearing an activity tracker.

- Data Flow Monitoring: Use the research dashboard to track the arrival of all expected data points in the central database.

- Message Trigger Verification: Confirm that the predefined self-monitoring data triggers the correct tailored feedback messages, which are delivered to participants' devices on schedule [1] [34].

- Troubleshooting Documentation: Log all failures (e.g., data not syncing, message not sent) and document their root causes and resolutions. This log becomes a primary resource for the study's technical support team.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Digital "Reagents" for mHealth Adherence Research

| Item / Platform | Function in Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Fitbit Charge / Sense Series | Wrist-worn accelerometer for capturing physical activity and sleep data. | Ease of use for participants; robust API for data extraction; battery life can impact continuous wear [1] [34]. |

| BodyTrace Cellular Scale | Transmits weight data directly via cellular networks, bypassing participant Wi-Fi. | Eliminates a major connectivity barrier; requires an active cellular service plan [34]. |

| MyFitnessPal / Fitbit App Food Database | Provides the nutrient database for dietary self-monitoring. | Database comprehensiveness affects logging burden; API stability is a known risk factor [34]. |

| Log2Lose-style Platform | A customizable platform for automating data collection, incentive processing, and participant messaging. | Critical for managing complex, fully remote trials; requires adaptable software and continuous technical support [34]. |

| System Usability Scale (SUS) | A standardized 10-item questionnaire for assessing the perceived usability of a system. | Provides a quick, reliable metric to compare usability across different versions of a research app [37]. |

This technical support center provides researchers and scientists with troubleshooting guides and FAQs to address common challenges in experiments focused on personalized nutrition for improving adherence to dietary weight loss interventions.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the core difference between traditional dietary advice and personalized nutrition? Traditional dietary advice offers a "one-size-fits-all" approach, assuming uniform metabolism across populations. In contrast, personalized nutrition tailors interventions based on an individual's unique genetic, epigenetic, microbiome, and real-time metabolic data to improve efficacy and adherence [38].

Q2: Which genetic variants are most relevant for personalizing carbohydrate and fat intake? Common genetic variations studied for dietary response include SNPs in genes like FTO and TCF7L2, which are linked to obesity and glucose metabolism. For instance, individuals with specific PPARG polymorphisms may respond better to a Mediterranean diet rich in monounsaturated fats [38] [39]. The table below summarizes key genetic factors.

| Gene | Associated Function | Dietary Implication | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| FTO | Risk of obesity & impaired glucose metabolism [38] | May benefit from tailored carbohydrate intake [38] | de Toro‐Martín et al. (2017) |

| TCF7L2 | Glucose metabolism [38] | May benefit from tailored carbohydrate intake [38] | de Toro‐Martín et al. (2017) |

| PPARG | Fat metabolism & adipocyte differentiation | Carriers may see superior weight loss on a high-monounsaturated fat diet [38] | Ferguson et al. (2016) |

| APOA2 | Lipid metabolism | Associated with higher obesity risk with high saturated fat intake; recommendation to reduce [38] | Lagoumintzis and Patrinos (2023) |

| MTHFR | Folate metabolism [39] | Variants (e.g., C677T) can lead to folic acid deficiency; requires supplementation [39] | - |

Q3: How can the gut microbiome be leveraged for personalized nutrition? The gut microbiome plays a critical role in nutrient absorption and metabolic health. Species like Akkermansia muciniphila are associated with improved insulin sensitivity. Diets can be personalized based on an individual's microbiome composition; for example, individuals with higher levels of beneficial bacteria may respond better to high-fiber interventions, which enhance short-chain fatty acid production [38].

Q4: What are the primary technical and ethical challenges in PN research? Key challenges include:

- Data Privacy: Managing sensitive genetic and health data [38].

- Clinical Validation: The need for robust, large-scale randomized controlled trials to substantiate efficacy [38] [39].

- Accessibility and Cost: Ensuring these strategies are accessible beyond a specific subgroup to have a widespread population health impact [38] [40].

Q5: What is the role of digital health technologies in modern PN studies? Digital tools are transformative for implementing and studying PN. Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGMs), AI-driven meal planning apps, and mobile health platforms enable dynamic dietary adjustments and real-time monitoring of adherence and metabolic parameters [38]. These tools facilitate the creation of Adaptive Personalized Nutrition Advice Systems (APNAS) that use dynamic data to guide both the "what" and "how" of dietary change [40].

Experimental Protocol Guide

Protocol: A Workflow for a Genetically-Informed Dietary Intervention Study

This protocol outlines a methodology for designing a weight loss intervention that incorporates nutrigenetic data.

1. Participant Genotyping & Group Allocation

- Method: Collect DNA samples (e.g., via saliva) from participants. Use genotyping arrays or targeted sequencing to identify relevant SNPs (e.g., in FTO, TCF7L2, PPARG) [38] [39].

- Troubleshooting: Ensure informed consent explicitly covers genetic analysis. Use standard DNA extraction kits and follow manufacturer protocols for optimal yield.

- Group Allocation: Randomize participants into a control group (general dietary advice) and an intervention group (genetically-tailored advice).

2. Baseline Phenotypic & Behavioral Assessment

- Clinical Measures: Collect baseline data on BMI, body composition (DEXA/BIA), and fasting blood markers (glucose, insulin, lipids) [38].

- Dietary & Behavioral Assessment: Use validated tools like 3-day food records or 24-hour recalls. Assess psycho-behavioral traits (e.g., eating behavior, motivation) via questionnaires [40].

3. Formulation & Delivery of Personalized Recommendations

- Algorithm Development: Create an algorithm that matches genetic profiles (from Step 1) to specific dietary prescriptions. For example, assign a lower glycemic load diet to carriers of certain TCF7L2 variants [38].

- Recommendation Delivery: Deliver advice via a dietitian or a digital platform. Digital apps can provide real-time feedback and nudges to enhance adherence [38].

4. Adherence & Outcome Monitoring

- Monitoring Adherence: Use digital food-tracking apps and, if feasible, objective biomarkers (e.g., CGM data, plasma fatty acid profiles) to track compliance [38] [40].

- Outcome Measurement: The primary outcome is often adherence rate (%) or weight loss (kg). Secondary outcomes include changes in body fat %, blood pressure, and glycemic markers [38].

Logical Workflow of a Personalized Nutrition Study

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details essential materials and tools for conducting state-of-the-art personalized nutrition research.

| Item Name | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Genotyping Array | Identifies single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with nutrient metabolism and disease risk [38] [39]. | Targets variants in genes like FTO, TCF7L2, MTHFR [38]. |

| 16S rRNA Sequencing Kit | Profiling gut microbiome composition to inform personalized pre/probiotic and fiber recommendations [38]. | Differentiates taxa such as Akkermansia muciniphila [38]. |

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) | Captures real-time, dynamic blood glucose data to understand individual postprandial responses to different foods [38] [40]. | - |

| Body Composition Analyzer | Precisely measures outcomes like body fat percentage, a more sensitive metric than body weight alone [38]. | DEXA Scan or Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA) device. |

| Dietary Assessment Platform | Digital tool for collecting high-frequency dietary intake data and monitoring adherence [38] [40]. | Mobile health applications with barcode scanners. |

| AI / Machine Learning Algorithm | Integrates multi-omics (genetic, microbiome), clinical, and behavioral data to generate and optimize personalized dietary plans [38] [40]. | - |

Nutrigenetics: From Gene to Dietary Advice

Frequently Asked Questions

What constitutes a 'structured support system' in weight loss research? Structured support systems are organized, methodical approaches designed to improve adherence and outcomes in dietary weight loss interventions. They primarily encompass two key elements: medically supervised weight management programs (MSWMPs) that provide clinical oversight and a structured curriculum [41], and social support mechanisms that leverage relationships with family, friends, or peers to encourage healthy eating and physical activity behaviors [42] [43].

Are short-term interventions effective for achieving significant weight loss? Yes, meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrate that multicomponent lifestyle interventions lasting 6 months or less can produce significant weight loss. A 2024 systematic review found a pooled mean difference in weight change of -2.59 kg (95% CI, -3.47 to -1.72) compared to control groups [44]. This suggests short-term programs can be a viable option, potentially improving enrollment and retention.

Which sources of social support are most impactful for weight management? Longitudinal studies indicate that different sources of support influence different behaviors [42]:

- Friend and Coworker Support: Most associated with improved healthy eating behaviors.

- Family Support: Most associated with improved physical activity behaviors. Conversely, family social undermining for healthy eating (e.g., bringing unhealthy foods) is significantly associated with weight gain [42].

How can cognitive modeling address the challenge of dietary self-monitoring adherence? The Adaptive Control of Thought-Rational (ACT-R) cognitive architecture can model and predict adherence dynamics. This computational framework simulates human cognitive processes like goal pursuit and habit formation over time. Model-based analyses can qualitatively test the impact of different intervention strategies, such as showing that tailored feedback combined with intensive support sustains goal pursuit and behavioral practice [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Declining Adherence to Dietary Self-Monitoring

Issue: Participant engagement with self-monitoring tools (e.g., food diaries, apps) wanes over time, a common challenge in long-term interventions [4].

Solution: Implement a multi-faceted support strategy based on cognitive modeling and behavioral theory.

Experimental Protocol: Dynamic ACT-R Modeling for Adherence [4]

- Objective: To develop a prognostic model for dietary self-monitoring adherence and simulate the effects of different support interventions.

- Methodology:

- Participant Assignment: Assign participants to one of three groups: basic self-management, tailored feedback, or intensive support.

- Data Collection: Collect longitudinal self-monitoring data (e.g., daily logins, food entries) over a minimum of 21 days.

- Cognitive Modeling: Use the ACT-R architecture to model adherence. The model incorporates:

- Declarative Memory: Chunks of knowledge about self-monitoring.

- Procedural Memory: Production rules for executing self-monitoring behavior.

- Subsymbolic Calculations: Computes activation levels for memory retrieval and utility for rule selection.

- Model Validation: Evaluate model performance using Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) to compare predicted vs. actual adherence.

- Intervention Simulation: Use the validated model to simulate and analyze the effects of varying support mechanisms on long-term adherence trends.

The workflow below illustrates the technical process of using cognitive modeling to understand and improve adherence.

Problem: Weight Loss Plateau

Issue: A participant experiences a state of little or no weight change after a period of active progress, typically for six weeks or more [45].

Solution: A holistic reassessment to identify and address underlying physiological and behavioral factors.

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Plateau Analysis [45] [46]

- Objective: To identify the physiological and behavioral determinants of a weight loss plateau and implement a targeted corrective strategy.

- Methodology:

- Reassess Baseline & Goals: Re-evaluate the participant's current dietary intake, physical activity level, and routine against their initial baseline. Confirm goal realism (e.g., 1 lb/week weight loss) [45].

- Audit Holistic Pillars: Systematically investigate key areas that impact metabolism and adherence:

- Sleep: Assess duration and quality. Sleep deprivation can decrease metabolism and increase hunger hormones [45].

- Stress: Evaluate perceived stress levels and management techniques. Chronic stress elevates cortisol, which can impair metabolism and promote emotional eating [45].

- Nutritional Deficiencies: Check for deficiencies in common micronutrients (e.g., Vitamin D, zinc, magnesium) or macronutrients (e.g., protein) that can cause low energy and hinder progress [46].

- Support System: Conduct an "inner circle inventory" to determine if the participant's close social contacts support or undermine their health goals [45].

- Adjust Energy Balance: Based on the reassessment, create a corrective action plan. This may involve:

The following decision tree provides a structured approach to diagnosing the root causes of a weight loss plateau.

Table 1: Weight Loss Outcomes from Structured Programs

| Program / Study Type | Duration | Sample Size | Weight Change from Baseline (kg) | Key Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medically Supervised Program (MSWMP) | 5 Years | 2,777 (with 5-yr data) | -6.4 kg (SE = 0.29) at 5 years | 35.2% achieved ≥10% weight loss at 5 years. | [41] |

| Short-Term Multicomponent Interventions (Meta-Analysis) | ≤6 Months | 14 RCTs (Pooled) | Pooled MD: -2.59 kg (95% CI: -3.47 to -1.72) | Effective for significant short-term loss; may improve enrollment. | [44] |

| Social-Support-Based Interventions (Meta-Analysis) | Varies (End of Intervention) | 24 RCTs (n=4,919) | Significant effect vs. control (p=0.04) | Effect significant at end of intervention and at 3- and 6-month follow-ups. | [43] |

This table summarizes longitudinal associations between specific sources of support/undermining and weight change over 24 months [42].

| Source & Type of Influence | Behavior Targeted | Association with Weight Change (β coefficient) | Statistical Significance (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Friend Support | Healthy Eating | β = -0.15 | p < 0.05 |

| Coworker Support | Healthy Eating | β = -0.11 | p < 0.05 |

| Family Support | Physical Activity | β = -0.032 | p < 0.05 |

| Family Social Undermining | Healthy Eating | β = +0.12 | p = 0.0019 |

β coefficient interpretation: A negative β indicates weight reduction; a positive β indicates weight gain.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Methodological Components for Adherence Research

| Research "Reagent" (Method/Tool) | Function / Purpose in the "Experiment" |

|---|---|

| ACT-R Cognitive Architecture | A computational framework to model and simulate the cognitive processes (goal pursuit, habit formation) underlying adherence dynamics over time [4]. |

| Social Support & Undermining Survey (Sallis) | A validated 23-item instrument to quantify perceived support and social undermining for healthy eating and physical activity from family, friends, and coworkers [42]. |

| Medically Supervised Program (MSWMP) Protocol | A standardized, multi-phase (meal replacement, transition, maintenance) intervention protocol to deliver structured, clinically supervised weight management [41]. |

| Digital Self-Monitoring Platform | A technology (e.g., mobile app) to collect continuous, fine-grained data on user dietary behaviors and adherence, enabling dynamic analysis [4]. |

| Holistic Pillar Assessment Framework | A structured protocol to audit key lifestyle factors (sleep, stress, nutrition, support system) that can confound weight loss outcomes and adherence [45] [46]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Adherence Barriers and Research Interventions

Table 1: Adherence Barriers and Proposed Mitigation Strategies for Research Protocols

| Adherence Barrier | Evidence from Clinical/Real-World Studies | Proposed Experimental Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal (GI) Side Effects | Most common adverse effects; nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, constipation [47] [48] [49]. Often dose-dependent and transient [50]. | Implement a forced, slow titration schedule in study design. Protocol to include prophylactic patient education on dietary modification (e.g., low-fat meals) and scheduled antiemetic use. |

| Patient Discontinuation & Non-Persistence | Real-world study: 46.3% persistence at 180 days; 32.3% at 1 year [51]. Another study: 22% discontinuation at 6 months [52]. | Integrate specialty pharmacy support for proactive follow-ups. Design trials with remote monitoring, dose adjustment support, and structured check-ins at high-risk periods (e.g., 3, 6, 9 months). |

| Access & Affordability Barriers | High drug cost leads to access issues; 54% of adults report difficulty affording therapy [53]. Insurance barriers (step therapy, prior authorization) cause delays [53]. | Incorporate a dedicated research coordinator to manage prior authorizations. Pre-screen participants for insurance coverage and integrate patient assistance programs into study protocols. |

| Management of Weight Regain | Observation of weight regain after treatment discontinuation is a key clinical concern [47]. | Design trials to include a combination therapy arm (e.g., GLP-1 RAs with behavioral therapy) and a structured tapering/discontinuation protocol to study rebound effects. |

| Aspiration Risk & Anesthesia | Delayed gastric emptying linked to increased aspiration risk during anesthesia [47] [48]. | Establish a mandatory pre-procedure drug withholding protocol (e.g., 1-week washout) for study participants undergoing elective anesthesia or endoscopy. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Clinical Research Design

Q1: What are the most critical safety signals to monitor in long-term trials involving GLP-1 RAs for weight management?

A: While early concerns about pancreatic and thyroid cancer have been largely attenuated by recent evidence [47], vigilant monitoring is recommended for:

- Gallbladder and Biliary Disorders: Recognized as potential risks [47] [48].

- Acute Pancreatitis: Although rare, it remains a serious adverse event to monitor [48] [49].

- Renal Function: Emerging real-world evidence suggests an increased risk of kidney conditions; routine monitoring of kidney function is essential [49].

- Psychiatric Safety: Requires ongoing investigation, though some studies indicate potential benefits for conditions like suicidal ideation and substance abuse [47] [49].