The Calorie Counting Conundrum: A Critical Analysis of Wearable Technology Accuracy for Biomedical Research

This article provides a critical evaluation of the accuracy and validity of wearable devices for tracking energy expenditure (EE), tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Calorie Counting Conundrum: A Critical Analysis of Wearable Technology Accuracy for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a critical evaluation of the accuracy and validity of wearable devices for tracking energy expenditure (EE), tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It synthesizes current evidence from meta-analyses and validation studies, revealing significant error margins in EE measurement that can exceed 25%. The scope covers foundational accuracy benchmarks, methodological considerations for integrating wearables into clinical and research protocols, strategies for troubleshooting inherent device limitations, and a comparative analysis of validation frameworks. The discussion focuses on the implications of these findings for interpreting data in clinical trials, epidemiological studies, and patient monitoring, offering a roadmap for the rigorous application of consumer wearables in scientific contexts.

Establishing the Baseline: Current Evidence on Wearable Calorie Tracking Accuracy

The accurate measurement of energy expenditure (EE) is fundamental to research in areas including metabolism, pharmacology, and public health. With the proliferation of wearable activity monitors in both consumer and research settings, quantifying the systemic error in these devices' EE estimates has become a critical endeavor. This guide objectively compares the EE measurement performance of major wearable devices against criterion measures, framing the findings within the broader thesis of accuracy validation for wearable calorie tracking research. The data presented herein, drawn from recent meta-analyses and validation studies, provides researchers with a quantitative basis for device selection and data interpretation.

Comparative Performance of Wearable Devices

Meta-analytic data reveals a consistent pattern across wearable devices: while they provide a practical means of estimating EE, their accuracy is substantially lower than for other metrics like heart rate or step count. The table below summarizes the quantitative findings from large-scale analyses.

Table 1: Meta-Analytic Summary of Wearable Device Accuracy for Energy Expenditure and Related Metrics

| Device / Analysis Focus | Mean Bias (EE) | Limits of Agreement (EE) | Mean Absolute Percent Error (MAPE) | Key Findings on EE Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fitbit (Combined-Sensing Models) [1] | -2.77 kcal/min | -12.75 to 7.41 kcal/min | Not Reported | Devices are likely to underestimate EE; accuracy may be unacceptable for some research purposes [1]. |

| Apple Watch [2] [3] | 0.30 kcal/min [3] | -2.09 to 2.69 kcal/min [3] | 27.96% [2] | Provides the strongest accuracy among consumer devices, but error rate is still high [2] [4]. |

| Archon Alive 001 [5] | Not Reported | Not Reported | 29.3% | Considered sufficient for monitoring exercise intensity but insufficient for clinical assessment [5]. |

| Garmin [4] | Not Reported | Not Reported | ~48.05% (Moderate Accuracy) | Identified as one of the least accurate for measuring calories burned [4]. |

| Actigraph (Research-Grade) [6] | No significant difference (SMD = 0.01) | Not Reported | Not Reported | Can be used for assessing total PAEE, but has limited validity for specific activity intensities [6]. |

| Comparative Metric | Mean Bias (Heart Rate) | Limits of Agreement (Heart Rate) | Mean Absolute Percent Error (MAPE) for Heart Rate | Mean Absolute Percent Error (MAPE) for Step Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fitbit [1] | -2.99 bpm | -23.99 to 18.01 bpm | Not Reported | Not Reported |

| Apple Watch [2] [3] | -0.12 bpm [3] | -11.06 to 10.81 bpm [3] | 4.43% [2] | 8.17% [2] |

| Archon Alive 001 [5] | -3.33 bpm | -31.55 to 24.90 bpm | Not Reported | 3.46% |

This systemic error in EE estimation is notably greater than for other common metrics. One large-scale meta-analysis of various brands found that while heart rate tracking showed strong accuracy (76.35%) and step count moderate accuracy (68.75%), the accuracy for energy expenditure was the lowest, at just 56.63% [4]. This underscores the particular challenge EE measurement presents for wearable algorithms.

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The quantitative findings in the previous section are derived from rigorous validation protocols. Understanding these methodologies is essential for researchers to critically evaluate the data and design their own validation studies.

Laboratory-Based Structured Protocols

The most common approach for high-quality validation involves controlled laboratory settings where wearable device outputs can be compared to criterion-standard measures.

- Criterion Measures for EE: Indirect Calorimetry (IC) is the most frequently used criterion measure for EE. It estimates energy expenditure by measuring respiratory gas exchange (oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production) using a metabolic analyzer such as the PNOĒ [5]. Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) is another gold standard for measuring total daily energy expenditure in free-living conditions, though it is less common in single-activity validation studies [1] [6].

- Criterion Measures for Heart Rate: An electrocardiogram (ECG) is the gold standard for heart rate validation. Research-grade chest strap systems (e.g., Polar H7/Polar OH1) are also used as reliable reference measures [1] [5] [7].

- Criterion Measures for Step Count: Direct observation (manual count by a researcher, often verified by video recording) serves as the primary criterion for step count [1] [5].

- Standardized Activity Protocols: Participants typically perform a series of structured activities while wearing the devices and the criterion equipment. A common treadmill protocol includes:

- Walking at varying speeds (e.g., 3, 4, and 5 km/h) [5].

- Running (e.g., 8 km/h) [5].

- Each stage lasts a set duration (e.g., 3 minutes) with rest periods in between.

- Other protocols may include graded cycling exercises and resistance training to assess device performance across different activity types and intensities [7].

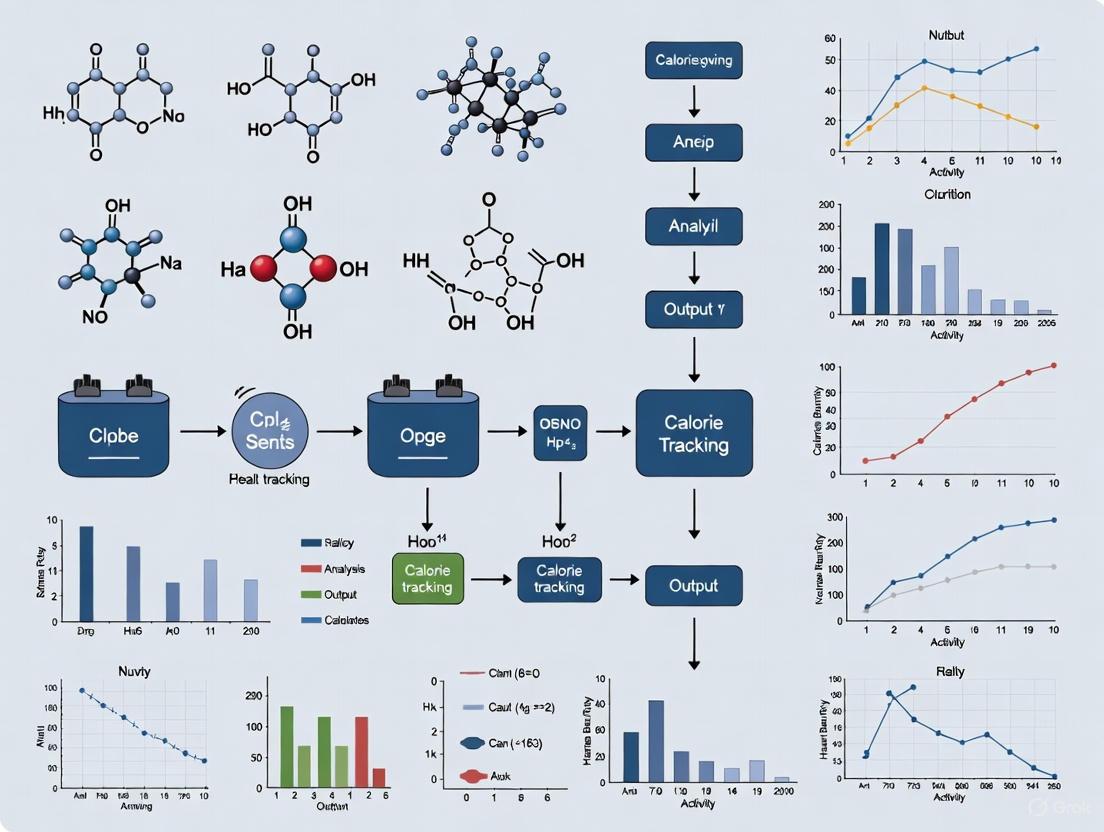

The following diagram illustrates a typical laboratory validation workflow.

Free-Living and Special Population Protocols

To complement laboratory studies, researchers also validate devices in free-living conditions and specific clinical populations, which introduces new challenges and considerations.

- Objective: To assess device performance in real-world environments and in populations whose movement patterns may differ from healthy adults (e.g., patients with lung cancer who often have slower gait speeds) [8].

- Protocol: Participants wear multiple devices (e.g., consumer-grade Fitbit Charge 6 and research-grade ActiGraph LEAP/activPAL) simultaneously for an extended period (e.g., 7 days) [8].

- Criterion Measures: In the absence of direct observation, data from research-grade devices is often used as a proxy criterion for comparison with consumer-grade devices. Surveys on health-related quality of life and symptom burden are administered to control for confounding factors [8].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key equipment and methodologies used in the validation of wearable activity monitors.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Wearable Validation Studies

| Item / Solution | Primary Function in Validation | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Indirect Calorimetry System | Serves as the criterion measure for Energy Expenditure (EE) by analyzing respiratory gases. | PNOĒ metabolic analyzer [5]; Medical-grade metabolic carts [6]. |

| Electrocardiogram (ECG) | Provides gold-standard measurement of heart rate for validating optical heart rate sensors. | 12-lead clinical ECG [9]; Single-lead ECG integrated into some wearables (e.g., Apple Watch) [9]. |

| Research-Grade Accelerometer | Used as a benchmark for validating step count and physical activity intensity in research settings. | Actigraph wGT3x-BT [5]; ActiGraph LEAP [8]. |

| Photoplethysmography (PPG) Reference | Provides a validated reference for optical heart rate monitoring. | Polar OH1 [5]; Polar H7 chest strap [7]. |

| Direct Observation / Video Recording | Serves as the criterion measure for validating step count and activity type. | Manual counting with a hand tally [5]; Video recording with subsequent blinded annotation [8]. |

| Standardized Treadmill | Provides a controlled environment for administering structured activity protocols at precise speeds. | Freemotion, iFIT, or other calibrated treadmills [5]. |

| Bland-Altman Analysis | A key statistical method for assessing agreement between the wearable device and the criterion measure. | Used to calculate mean bias and 95% Limits of Agreement (LoA) [1] [5] [3]. |

| Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) | A standard metric for quantifying accuracy as a percentage of error. | Calculated as the average of absolute errors divided by actual values [2] [5]. |

Meta-analytic evidence quantifies a significant systemic error in the energy expenditure estimates provided by wearable devices, with most exhibiting a mean absolute percent error between 27% and 48%. This error is markedly larger than that for heart rate or step count. While consumer devices like the Apple Watch show relatively stronger performance, and research-grade tools like the Actigraph are valid for assessing total physical activity energy expenditure, all devices have limitations. The accuracy of EE measurement is influenced by the type of physical activity, the device model, and user demographics. Researchers must therefore incorporate these known errors into their study design and interpretation, utilizing wearable EE data as a useful but approximate indicator rather than a definitive measure.

Wearable activity monitors have become integral tools in health and fitness, offering users insights into their physical activity, cardiovascular function, and energy expenditure. For researchers and clinicians, understanding the comparative accuracy of these devices across different metrics is crucial for interpreting data, designing studies, and making clinical recommendations. This guide objectively compares the performance of wearable devices in tracking steps, heart rate, and calories, framing the analysis within the broader context of accuracy validation for wearable calorie tracking research. The analysis synthesizes findings from recent validation studies, details experimental methodologies, and provides resources to support further scientific investigation.

A consistent pattern emerges from recent validation studies: the accuracy of wearable devices varies significantly depending on the metric being measured. Step counting and heart rate monitoring demonstrate notably higher accuracy compared to the estimation of energy expenditure.

- Step Count: This is generally the most reliable metric, with high-fidelity devices like the Apple Watch and Archon Alive tracker showing mean absolute percentage errors (MAPE) of approximately 3-8% under controlled conditions [2] [5]. This high accuracy is attributed to the well-established use of accelerometers to detect rhythmic arm movements associated with walking and running.

- Heart Rate: Heart rate tracking also shows good agreement with gold-standard measures, such as electrocardiogram (ECG) and chest straps. Studies report percentage errors around 4-5% for devices like the Apple Watch, and Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC) of 75.8% for affordable trackers like the Archon Alive [2] [5] [10]. The underlying photoplethysmography (PPG) technology, while effective, can be influenced by motion and device fit.

- Calories Burned (Energy Expenditure): This is the least accurate metric, with errors substantially higher than for steps or heart rate. Meta-analyses and validation studies consistently report MAPE values around 28-30% for this metric [2] [5] [11]. The high error rate stems from the indirect nature of the calculation, which relies on proprietary algorithms that estimate a complex physiological process from a limited set of inputs like heart rate and movement.

Comparative Performance Data

The following tables summarize quantitative data on device accuracy from recent scientific studies.

Table 1: Summary of Device Accuracy Across Key Metrics from Recent Studies

| Device / Study | Step Count Accuracy (MAPE) | Heart Rate Accuracy | Calorie Expenditure Accuracy (MAPE) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apple Watch (Meta-analysis) | 8.17% (MAPE) | 4.43% (MAPE) | 27.96% (MAPE) | [2] [11] |

| Archon Alive 001 | 3.46% (MAPE vs. hand tally) | ICC: 75.8% (vs. Polar OH1) | 29.3% (MAPE vs. PNOĒ) | [5] |

| Actigraph wGT3x-BT | 31.46% (MAPE vs. hand tally) | Not Reported in Study | Not Reported in Study | [5] |

| Corsano CardioWatch (Pediatric) | Not Reported in Study | 84.8% of readings within 10% of Holter ECG | Not Reported in Study | [10] |

| Hexoskin Smart Shirt (Pediatric) | Not Reported in Study | 87.4% of readings within 10% of Holter ECG | Not Reported in Study | [10] |

Table 2: Impact of External Factors on Metric Accuracy

| Factor | Impact on Step Count | Impact on Heart Rate | Impact on Calorie Expenditure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activity Type/Speed | Accuracy decreases at very slow walking speeds [5] [8]. | Accuracy decreases during high-intensity movement [10]. | Inaccurate across walking, running, cycling, and mixed-intensity workouts [2]. |

| Population | Gait impairments (e.g., in lung cancer patients) can reduce accuracy [8]. | Accuracy lower in children with higher, more variable heart rates [10]. | Individual factors (age, weight, metabolism) not fully captured by algorithms [12]. |

| Device Grade | Consumer-grade (e.g., Archon) can outperform research-grade (e.g., Actigraph) in specific protocols [5]. | Research-grade and medically certified devices may offer higher reliability for clinical applications [10] [8]. | Proprietary algorithms vary significantly between brands; no consumer device is highly accurate [2] [13]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To critically assess the data presented in comparison tables, an understanding of the underlying experimental methodologies is essential. The following are detailed protocols from key studies cited in this guide.

Protocol 1: Validation of an Affordable Fitness Tracker

This 2025 study validated the Archon Alive 001 against criterion measures in a controlled laboratory setting [5].

- Objective: To assess the validity of the Archon Alive 001 for measuring step count, heart rate, and energy expenditure.

- Participants: Approximately 35 adults with a BMI between 18-25 kg/m² and no chronic diseases or mobility restrictions.

- Criterion Measures:

- Step Count: Manual hand tally.

- Heart Rate: Polar OH1 (a validated PPG heart rate monitor).

- Energy Expenditure: PNOĒ metabolic analyzer (portable cardio-metabolic analyzer of breath).

- Protocol: Participants walked or ran on a treadmill at four set speeds: 3, 4, 5, and 8 kilometers per hour. Each stage lasted 3 minutes with a 1-minute break in between. The Archon Alive and Actigraph wGT3x-BT were worn on the non-dominant wrist, while the Polar OH1 was worn on the upper arm. The PNOĒ was fastened to the participant's back, with the participant breathing through a Hans Rudolph mask.

- Data Analysis: Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) was calculated for step count and calorie expenditure against the criterion. For heart rate, Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) and Bland-Altman analysis (including bias and limits of agreement) were used to compare the Archon Alive with the Polar OH1.

Protocol 2: A Meta-Analysis of Apple Watch Accuracy

This 2025 study from the University of Mississippi provides a high-level overview of Apple Watch performance based on a synthesis of existing research [2] [11].

- Objective: To evaluate the accuracy of the Apple Watch in measuring energy expenditure, heart rate, and step counts across different user demographics and activities.

- Methodology (Meta-analysis): Researchers identified and systematically reviewed 56 individual studies that compared Apple Watch data to trusted reference tools. The analysis specifically evaluated how accuracy varied by age, health status, Apple Watch version, and type of physical activity (e.g., walking, running, cycling).

- Data Analysis: The core of the analysis was the calculation of the mean absolute percent error (MAPE), a standard measure of accuracy, for each of the three key metrics across the aggregated studies.

Protocol 3: Validation of Wearables in a Pediatric Clinical Population

This 2025 study assessed the accuracy of two wearables in a pediatric cardiology cohort, highlighting the importance of validation in specific populations [10].

- Objective: To assess the heart rate accuracy and validity of the Corsano CardioWatch bracelet and the Hexoskin smart shirt in children with congenital heart disease or suspected arrhythmias.

- Participants: 31 participants for the CardioWatch and 36 for the Hexoskin shirt (mean age ~13 years).

- Criterion Measure: 24-hour Holter electrocardiogram (ECG), the gold standard for ambulatory heart rate monitoring.

- Protocol: Participants were equipped with the Holter ECG and both wearables simultaneously for a 24-hour free-living period. They were encouraged to maintain their normal daily routine but refrain from showering and swimming.

- Data Analysis: Accuracy was defined as the percentage of heart rate readings from the wearables that fell within 10% of the concurrent Holter ECG values. Agreement was further assessed using Bland-Altman analysis. Subgroup analyses were conducted based on factors like BMI, age, time of wearing, and accelerometry-measured bodily movement.

Experimental Workflow and Logical Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow and logical relationships involved in validating a wearable device's metrics, as demonstrated by the protocols above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers aiming to replicate or design validation studies, the following table details essential equipment and their functions as derived from the cited protocols.

Table 3: Essential Materials for Wearable Validation Research

| Item | Function in Validation Research | Example from Search Results |

|---|---|---|

| Criterion Measure for Energy Expenditure | Provides a gold-standard measurement of calorie burn/energy expenditure via gas analysis for validating wearable estimates. | PNOĒ metabolic analyzer [5]. |

| Criterion Measure for Heart Rate | Provides a gold-standard measurement of heart rate and rhythm for validating optical heart rate sensors. | Holter ECG [10] & Polar OH1 chest strap/armband [5]. |

| Criterion Measure for Step Count | Provides a ground-truth measure of steps taken during controlled trials. | Manual hand tally [5]. |

| Controlled Activity Generator | Allows for standardized, repeatable physical activities at various intensities to test device performance across a range of metabolic demands. | Freemotion T10.8 Treadmill [5]. |

| Research-Grade Activity Monitor | Serves as a benchmark device, often used in public health research, for comparison with consumer-grade trackers. | Actigraph wGT3x-BT [5] [8]. |

| Data Analysis Software | Used for processing raw data and conducting specialized statistical analyses to quantify agreement and error. | ActiLife (for Actigraph data) [5]; Statistical packages for Bland-Altman, ICC, MAPE [5] [10]. |

The collective evidence indicates a clear hierarchy in the accuracy of metrics provided by consumer wearable devices. Steps and heart rate can be measured with a reasonable degree of confidence for general tracking and trend analysis, making them suitable for a wide range of research applications. In contrast, energy expenditure (calorie burn) remains an inaccurate metric, with errors too high for precise scientific or clinical use. Researchers and professionals should therefore prioritize devices with strong validation data for steps and heart rate, treat calorie estimates with significant caution, and always consider the target population and specific use case when selecting and implementing wearable technology in studies.

The accuracy of calorie measurements from wearable devices is not a fixed value but a variable dependent on a complex interplay of factors. For researchers and professionals in drug development and clinical sciences, understanding these variables is critical when considering the use of consumer wearables in research protocols or health interventions. This guide objectively compares the performance of various wearable devices, framing their accuracy within the broader thesis of validation research. The data reveals that accuracy is predominantly influenced by the type and intensity of physical activity performed by the user, as well as their individual demographic characteristics. A synthesis of current studies indicates that while some metrics like heart rate can be measured with reasonable reliability, energy expenditure (EE) remains a significant challenge, with even the best-performing devices showing considerable error rates [14] [15]. This analysis provides a structured comparison of device performance, detailed experimental methodologies from key studies, and essential resources for the validation of wearable calorie tracking.

Quantitative Data Comparison of Wearable Devices

The tables below summarize the accuracy of various commercial wearable devices for measuring energy expenditure (calories burned), heart rate, and step count, as reported in validation studies. This data allows for a direct, objective comparison of device performance across key metrics.

Table 1: Overall Accuracy of Wearables by Metric (WellnessPulse Analysis)

| Metric | Cumulative Accuracy | Notes on Variation |

|---|---|---|

| Heart Rate (HR) | 76.35% | Most accurate metric; Apple Watch showed highest accuracy (86.31%) [4]. |

| Step Count (SC) | 68.75% | Accuracy can drop for non-ambulatory movements [4]. |

| Energy Expenditure (EE) | 56.63% | Least accurate metric; highly variable across devices and activities [4]. |

Table 2: Device-Specific Error Rates for Key Metrics

| Device Brand | Energy Expenditure (EE) Error | Heart Rate (HR) Error | Step Count (SC) Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apple Watch | MAPE: -6.61% to 53.24% [16]Overall Accuracy: 71.02% [4] | Underestimation: ~1.3 BPM during exercise [16]Overall Accuracy: 86.31% [4] | Error: 0.9-3.4% [16]Overall Accuracy: 81.07% [4] |

| Fitbit | MAPE: ~0.44 [15]Error: 14.8% [16]Overall Accuracy: 65.57% [4] | Underestimation: ~9.3 BPM during exercise [16]Overall Accuracy: 73.56% [4] | Error: 9.1-21.9% [16]Overall Accuracy: 77.29% [4] |

| Garmin | Error: 6.1-42.9% [16]Overall Accuracy: 48.05% [4] | Error: 1.16-1.39% [16] | Error: 23.7% [16]Overall Accuracy: 82.58% [4] |

| Samsung Gear S3 | MAPE: Up to 0.44 [15] | MAPE from 0.04 (at rest) to 0.34 [15] | Data not reported in analysis |

| Polar | Error: 10-16.7% [16]Overall Accuracy: 50.23% [4] | Error: 2.2% (upper arm) [16] | Overall Accuracy: 53.21% [4] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To critically assess the data from wearables, understanding the underlying validation methodologies is essential. The following are detailed protocols from two key studies that exemplify rigorous device testing.

Protocol 1: Multi-Device Validation Under Semi-Naturalistic Conditions

A 2018 comparative study by Lei et al. evaluated the validity of several mainstream wearable devices under various physical activities [15].

- Objective: To evaluate the accuracy of multiple wearable devices in measuring heart rate, steps, distance, energy consumption, and sleep duration across different activity states.

- Subjects: 44 healthy subjects were recruited for the study.

- Devices & Comparators: Each subject simultaneously wore six devices: Apple Watch 2, Samsung Gear S3, Jawbone Up3, Fitbit Surge, Huawei Talk Band B3, and Xiaomi Mi Band 2. Two smartphone apps (Dongdong and Ledongli) were also included.

- Activity Protocol: Subjects performed activities in various states:

- Resting: To establish baseline heart rate.

- Walking: To simulate light-to-moderate activity.

- Running: For high-intensity dynamic movement.

- Cycling: For non-ambulatory exercise.

- Sleeping: For sleep duration tracking.

- Gold Standard Measures:

- Heart Rate: Manually measured (likely via electrocardiogram or palpation).

- Steps & Distance: Manually counted and measured.

- Energy Expenditure: Measured via oxygen consumption (indirect calorimetry).

- Sleep Duration: Manually recorded.

- Data Analysis: The Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) was calculated for each device and metric against the gold standard. The study found high accuracy for heart rate, steps, distance, and sleep (MAPE ~0.10), but poor accuracy for energy consumption (MAPE up to 0.44) [15].

Protocol 2: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Methodology

A 2020 systematic review in PMC provides a broader overview of device accuracy by synthesizing data from 158 publications [14].

- Objective: To examine the validity and reliability of commercial wearables in measuring step count, heart rate, and energy expenditure.

- Search Strategy: Comprehensive searches were conducted in PubMed, Embase, and SPORTDiscus up to May 2019. The strategy used controlled vocabulary and text words related to wearables, validity, and specific brands.

- Eligibility Criteria:

- Included studies using consumer-grade wearables (e.g., Apple, Fitbit, Garmin).

- Focused on studies examining reliability or validity of step count, heart rate, or energy expenditure.

- Excluded studies with fewer than 10 participants and those focusing on research-grade devices.

- Data Extraction & Synthesis: Researchers extracted key study characteristics and outcome data, including correlation coefficients, percentage differences, and MAPE values. Where possible, group percentage error was calculated to standardize comparisons across studies.

- Key Findings:

- In laboratory settings, Fitbit, Apple Watch, and Samsung were most accurate for steps.

- Heart rate accuracy was variable, with Apple Watch and Garmin being most accurate.

- No brand was accurate for measuring energy expenditure [14].

Visualizing Influencing Factors on Accuracy

The diagram below illustrates the logical relationship between the key influencing factors (activity type, intensity, and demographics) and their combined impact on the accuracy of calorie measurements in wearable devices.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

For researchers designing validation studies for wearable devices, the following table details essential equipment and their functions, as derived from the cited experimental protocols.

Table 3: Essential Materials for Wearable Validation Research

| Item | Function in Validation Research |

|---|---|

| Indirect Calorimeter | Considered the "gold standard" for measuring energy expenditure. It calculates calories burned by measuring oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production [15]. |

| Electrocardiogram (ECG) | Serves as the gold standard for heart rate measurement. Provides a medical-grade reference to which optical heart rate sensors from wearables are compared [4]. |

| Research-Grade Actigraph | Provides high-fidelity, validated data on step count and movement acceleration, often used as a benchmark for consumer-grade activity trackers [14]. |

| Manual Step Counter/Tally | Used for direct, observable counting of steps during controlled walking or running protocols, providing a simple and accurate ground truth [15]. |

| Gold Standard Sleep Polysomnography (PSG) | The comprehensive reference method for validating sleep metrics tracked by wearables, measuring brain waves, eye movement, muscle activity, and more [16]. |

Wearable fitness trackers have become ubiquitous in both consumer and clinical settings. However, for researchers and scientists relying on this data, a significant gap exists between the number of devices on the market and those that have undergone rigorous, peer-reviewed validation. This guide objectively compares the validation status of various wearable devices and details the experimental methodologies used to assess their accuracy.

The Scale of the Validation Gap

The market for wearable fitness trackers is expanding rapidly, projected to grow from USD 35.8 billion in 2025 to USD 144.8 billion by 2035 [17]. Despite this proliferation, a relatively small fraction of commercially available devices have been scientifically validated.

The table below quantifies this validation gap, synthesizing data from a large-scale 2024 living umbrella review of systematic reviews [18].

Table 1: Peer-Reviewed Validation Status of Commercial Wearable Devices

| Metric | Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Total Commercially Available Wearables | 310 devices released to date | [18] |

| Devices Validated for ≥1 Biometric | ~11% (approximately 34 devices) | [18] |

| Total Possible Biometric Outcomes | All measurable metrics (e.g., HR, EE, sleep) across all devices | [18] |

| Validated Biometric Outcomes | ~3.5% of total possible outcomes | [18] |

This comprehensive review highlights a critical challenge for the research community: the vast majority of wearable devices and the data they produce lack independent, peer-reviewed assessment against accepted reference standards [18].

Accuracy of Validated Metrics by Device Type

For the subset of devices that have been validated, accuracy varies significantly by the biometric being measured and the specific device model. The following tables summarize key accuracy metrics for common tracking domains.

Table 2: Accuracy of Heart Rate and Step Count Tracking

| Device / Study Focus | Heart Rate Accuracy (MAPE or Mean Bias) | Step Count Accuracy (MAPE or Mean Bias) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apple Watch (Meta-Analysis) | Mean Bias: -0.12 bpm; MAPE: 4.43% | Mean Bias: -1.83 steps/min; MAPE: 8.17% | [2] [3] |

| Various Wearables (Umbrella Review) | Mean Absolute Bias: ±3% | Mean Absolute Percentage Error: -9% to 12% | [18] |

| Multiple Brands (2018 Study) | MAPE range: 12%-34% (varies by brand/activity) | MAPE range: 1%-42% (varies by brand/activity) | [15] |

Table 3: Accuracy of Energy Expenditure and Other Metrics

| Device / Study Focus | Energy Expenditure (Calories) Accuracy | Other Metrics | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apple Watch (Meta-Analysis) | Mean Bias: 0.30 kcal/min; MAPE: 27.96% | N/A | [2] [3] |

| Various Wearables (Umbrella Review) | Mean Bias: -3 kcal/min (range: -21.27% to 14.76%) | Aerobic Capacity (VO₂max): Overestimation by 9.83%-15.24%Sleep: Tends to overestimate total sleep time (MAPE >10%) | [18] |

| Multiple Brands (2018 Study) | MAPE up to 44% (varies by brand/activity) | Sleep Duration: High accuracy (MAPE ~0.10) | [15] |

The data consistently shows that while heart rate and step count are generally measured with reasonable accuracy, energy expenditure (calorie burn) is a particularly challenging metric for all wearable devices, with error rates often exceeding what is considered clinically valid [2] [18] [15]. Newer models show a trend of gradual improvement, and recent research is developing more accurate algorithms for specific populations, such as individuals with obesity [2] [19].

Experimental Protocols for Validating Wearables

To critically assess validation studies, researchers must understand the standard experimental protocols and reference standards used. The following workflow diagram outlines a typical validation study design.

Participant Recruitment and Instrumentation

Studies typically recruit a cohort of healthy adult subjects, though recent research increasingly focuses on specific clinical populations (e.g., individuals with obesity) [19]. Sample sizes vary, with smaller studies involving around 20-50 participants [15] [19] and larger meta-analyses synthesizing data from hundreds of thousands of individuals [18]. Participants are simultaneously fitted with the consumer wearable device(s) under test and the research-grade reference equipment.

Controlled Activity Protocol

A critical phase involves subjects performing a structured set of activities while being monitored. This protocol is designed to assess device performance across different physiological states and movement patterns. A typical protocol includes:

- Resting State: To establish baselines for heart rate and metabolic rate.

- Ambulatory Activities: Such as walking and running at controlled speeds, often on a treadmill.

- Cycling: Using stationary bikes.

- Activities of Daily Living: And, in more recent studies, free-living conditions, sometimes with body cameras for ground truth annotation [15] [19].

Gold Standard Reference Measures

The accuracy of wearable devices is judged by comparing their data outputs to those from accepted gold standard clinical and research tools. The table below lists key reference methods.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Validation Studies

| Resource / Tool | Function in Validation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Cart | Measures oxygen consumption (VO₂) and carbon dioxide production (VCO₂) to calculate Energy Expenditure via indirect calorimetry. Considered a gold standard. | Used as criterion measure for validating calorie burn estimates during rest and various physical activities [19]. |

| Electrocardiogram (ECG) | Provides clinical-grade measurement of heart rate and heart rhythm. | Used as a reference for validating optical heart rate sensors on wearable devices [15] [12]. |

| Manually Counted Steps | Provides a ground-truth measure of step count. | Serves as a simple, accurate reference for validating pedometer functions during walking/running protocols [15]. |

| Polysomnography (PSG) | Comprehensive sleep study tracking brain waves, blood oxygen, heart rate, breathing, and eye/leg movements. | Used as a gold standard for validating wearable-derived sleep stage and sleep duration data [18]. |

| Actigraphy | A research-grade activity monitor, often worn on the wrist or hip. | Sometimes used as a higher-grade benchmark against which consumer devices are compared [12]. |

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

Data from the wearable devices and reference standards are time-synchronized and processed. Common statistical measures used to report validity include:

- Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE): The average absolute percentage difference between the device and the reference standard.

- Mean Bias: The average difference between the device and the reference standard, indicating systematic over- or under-estimation.

- Limits of Agreement (LoA): Often derived from Bland-Altman analysis, showing the range within which 95% of the differences between the two measurement methods lie [3].

- Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC): Measures the reliability or consistency between the device and the gold standard measurements.

The Scientist's Toolkit

For researchers incorporating wearable data into clinical trials or scientific studies, understanding the components of a robust validation framework is essential. The following table details key resources.

Table 5: Essential Research Toolkit for Wearable Validation

| Tool / Resource Category | Specific Examples | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Standard Reference Devices | Metabolic cart, ECG, Polysomnography system | Provide the criterion measure against which consumer device accuracy is judged [15] [19]. |

| Standardized Validation Protocols | INTERLIVE Network recommendations, FIMS global standards | Ensure consistency, comparability, and rigor across different validation studies [18]. |

| Open-Source Algorithms & Software | Northwestern's dominant-wrist algorithm for obesity | Enable transparency, replication, and improvement of data processing methods, especially for underrepresented groups [19]. |

| Living Evidence Syntheses | "Living" umbrella reviews (e.g., [18]) | Provide continuously updated assessments of device accuracy in a rapidly evolving market, crucial for informed decision-making. |

| Data Privacy & Security Framework | Institutional review board (IRB) protocols, data anonymization tools | Protect sensitive participant health data collected by wearables, a major ethical and legal requirement [12] [20]. |

The wearable device market is characterized by a significant validation gap, with only an estimated 11% of devices validated for at least one biometric outcome [18]. For the devices that have been assessed, accuracy is highly metric-dependent, with heart rate and step counts being generally reliable, while energy expenditure measurements often contain substantial errors. Researchers must prioritize the use of devices and metrics with established validity for their specific population of interest and must be critical consumers of validation literature, paying close attention to the experimental protocols and reference standards used. The development of standardized validation frameworks and living evidence syntheses is crucial to bridge this gap and ensure that wearable-generated data meets the rigorous standards required for scientific and clinical application.

From Data to Discovery: Methodological Frameworks for Research Applications

Standardized Protocols for Validating Wearables in Specific Populations

The accuracy of data from wearable devices is not uniform; it varies significantly across different biometric outcomes and is highly dependent on the specific population being studied. For researchers and drug development professionals, employing standardized validation protocols is paramount to ensuring that wearable-generated endpoints are reliable, clinically meaningful, and fit for purpose in clinical trials and scientific studies. This guide objectively compares the performance of various wearables and details the experimental methodologies essential for their rigorous validation.

Quantitative Accuracy of Wearable Devices

The table below summarizes the accuracy of consumer wearables for various biometric measures, as synthesized from systematic reviews and primary validation studies. This data serves as a benchmark for comparing device performance.

Table 1: Accuracy of Wearable Devices for Key Biometric Measures

| Biometric Measure | Device(s) Tested | Reference Standard | Accuracy Metric | Reported Performance | Context & Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step Count | Archon Alive 001 [5] | Manual hand tally | Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) | 3.46% MAPE | Controlled treadmill walking (3-8 kph) in healthy adults [5] |

| Actigraph wGT3x-BT [5] | Manual hand tally | Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) | 31.46% MAPE | Controlled treadmill walking (3-8 kph) in healthy adults [5] | |

| Heart Rate (HR) | Corsano CardioWatch [21] | Holter ECG | Bias (BPM); 95% LoA | -1.4 BPM; -18.8 to 16.0 | 24-hour free-living, children with heart disease [21] |

| Hexoskin Smart Shirt [21] | Holter ECG | Bias (BPM); 95% LoA | -1.1 BPM; -19.5 to 17.4 | 24-hour free-living, children with heart disease [21] | |

| Archon Alive 001 [5] | Polar OH1 | ICC; Bias (BPM) | ICC 75.8%; -3.33 BPM | Controlled treadmill walking and running [5] | |

| Calorie Expenditure | Archon Alive 001 [5] | PNOĒ metabolic analyzer | Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) | 29.3% MAPE | Controlled treadmill walking and running [5] |

| Heart Rate (General) | Various Consumer Wearables [18] | Clinical-grade devices | Mean Absolute Bias | ± 3% | Synthesis of 24 systematic reviews [18] |

| Aerobic Capacity (VO₂max) | Various Consumer Wearables [18] | Clinical gas analysis | Overestimation | 9.83% - 15.24% | Synthesis of 24 systematic reviews [18] |

| Sleep Measurement | Various Consumer Wearables [18] | Polysomnography | Tendency to Overestimate | MAPE > 10% | Synthesis of 24 systematic reviews [18] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Validation

A robust validation protocol must define the context of use, population, and rigorous methodology against an accepted reference standard.

Protocol for Validating Heart Rate in Pediatric Cardiology

This protocol is based on a prospective cohort study validating two wearables in children with heart disease [21].

- Objective: To assess the accuracy and patient satisfaction of the Corsano CardioWatch (wristband) and Hexoskin smart shirt in children with congenital heart disease or suspected arrhythmias.

- Population: 31-36 pediatric participants (mean age ~13 years) indicated for 24-hour Holter monitoring [21].

- Reference Standard: 24-hour Holter electrocardiogram (ECG), applied by a certified nurse [21].

- Device Setup:

- CardioWatch: Worn tightly on the non-dominant wrist, connected via Bluetooth to a smartphone for data syncing [21].

- Hexoskin Shirt: Appropriate size selected based on chest circumference. Electrode transmission gel applied for better signal conduction. Holter electrodes were placed strategically to avoid interference with the shirt's electrodes [21].

- Procedure: Participants wore all three devices (Holter, CardioWatch, Hexoskin) simultaneously for a 24-hour free-living period. They were encouraged to maintain their normal routine but avoid showering and swimming. A symptom and activity diary was maintained [21].

- Data Analysis:

- Accuracy: Defined as the percentage of heart rate measurements within 10% of Holter values. Agreement was assessed using Bland-Altman analysis (bias and 95% Limits of Agreement) [21].

- Subgroup Analysis: Accuracy was analyzed based on factors like BMI, age, time of wearing, and heart rate zone [21].

- Patient Satisfaction: Measured using a 5-point Likert scale questionnaire and compared to satisfaction with the Holter monitor [21].

The following workflow diagrams the key stages of this pediatric validation protocol:

Protocol for Validating Step Count and Calorie Expenditure

This protocol outlines a controlled laboratory study to validate an affordable fitness tracker's core metrics [5].

- Objective: To assess the validity of the Archon Alive 001 for step count, heart rate, and energy expenditure during treadmill walking and running.

- Population: Healthy adults (BMI 18-25 kg/m²) with no contraindications to exercise [5].

- Reference Standards:

- Device Placement: The Archon Alive and Actigraph (used for step count comparison) were randomized on the non-dominant wrist. The Polar OH1 was placed on the upper arm [5].

- Treadmill Protocol: Participants completed stages at 3, 4, 5, and 8 km/h, each lasting 3 minutes with 1-minute rest intervals [5].

- Data Analysis:

- Step Count: Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) was calculated relative to hand tally. A MAPE ≤ 3% was considered clinically irrelevant. Multivariate analysis of variance (MANCOVA) assessed the effect of speed and demographics on accuracy [5].

- Heart Rate: Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) and Bland-Altman analysis (bias, 95% LoA) against the Polar OH1 [5].

- Calorie Expenditure: MAPE and correlation (r) against the PNOĒ analyzer [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers designing validation studies, the following table details essential materials and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Materials for Wearable Validation Studies

| Item Name | Function in Validation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Holter Electrocardiogram (ECG) | Gold standard for ambulatory heart rate and rhythm monitoring [21]. | Validating wearable heart rate and arrhythmia detection in clinical populations [21]. |

| Portable Metabolic Analyzer (e.g., PNOĒ) | Gold standard for measuring energy expenditure (calories) via gas analysis [5]. | Validating calorie expenditure algorithms in wearables during controlled exercise [5]. |

| Research-Grade Accelerometer (e.g., ActiGraph) | Objective measure of physical activity and step count; considered a criterion device in research [5]. | Benchmarking the step count and activity intensity accuracy of consumer wearables [5]. |

| Photoplethysmography (PPG) Sensor (e.g., Polar OH1) | Provides validated heart rate data from a wearable form factor [5]. | Serving as a reference for optical heart rate sensors in consumer wristbands [5]. |

| Medical-Grade Biosensor (e.g., Everion) | Provides aggregated, validated accelerometer and physiological data for continuous monitoring [22]. | Calibrating less accurate but more unobtrusive ambient sensor systems (e.g., passive infrared sensors) [22]. |

Navigating the Regulatory and Validation Pathway

Integrating wearables into clinical research requires adherence to a rigorous regulatory and scientific pathway to ensure data quality and regulatory compliance.

- Context of Use (COU) is Critical: The FDA and other regulators require that validation be performed for the specific context of use. A device validated for general wellness tracking is not automatically qualified for use as a clinical trial endpoint [23] [24].

- Analytical and Clinical Validation: The validation process has two key stages [23] [24]:

- Analytical Validation: Does the device measure the physiological parameter accurately and reliably? This is tested against a reference standard in a controlled setting.

- Clinical Validation: Does the measurement correlate with a clinically meaningful endpoint or outcome in the target population?

- Global Regulatory Considerations: The regulatory landscape is fragmented. The FDA's Digital Health Innovation Action Plan and the EMA's framework emphasize data quality, security, and clinical validation. Multinational trials must navigate regional variations, including GDPR compliance in Europe and local certification requirements in Asia-Pacific countries [24].

The diagram below illustrates the key stages a wearable must pass through to be deemed suitable for clinical research.

Key Considerations for Specific Populations

- Pediatric and Young Adult Populations: A scoping review revealed that wearable studies in pediatric oncology primarily use devices like ActiGraph and Fitbit to monitor physical activity and sleep, often as data collection tools rather than active interventions [25]. Validation in children is crucial as their higher, more variable heart rates and activity patterns differ significantly from adults [21].

- Older Adults: This population may prefer unobtrusive, contactless monitoring systems (e.g., passive infrared sensors) due to discomfort or difficulty with wearable devices. A promising strategy is to use wearable biosensors for initial calibration of these ambient systems to improve their accuracy for quantifying in-home physical activity [22].

In conclusion, the journey toward standardized validation is ongoing. While significant variability in device accuracy persists [18], the research community is moving toward more rigorous, population-specific testing frameworks. By adhering to detailed experimental protocols and understanding the regulatory pathway, researchers can confidently leverage wearable technology to generate high-quality, clinically relevant data.

Integrating Wearable EE Data with Gold-Standard Measures (e.g., Indirect Calorimetry)

The accurate measurement of energy expenditure (EE) is fundamental to research in metabolism, nutrition, and exercise physiology. While wearable fitness trackers have democratized access to personal activity data, their integration with gold-standard measures like indirect calorimetry remains crucial for validating and improving their accuracy in research settings. Energy expenditure consists of three components: resting energy expenditure (approximately 60%), physical activity energy expenditure (PAEE, approximately 30%), and diet-induced thermogenesis (approximately 10%) [26]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the alignment between consumer-grade wearable data and laboratory standards is essential for determining appropriate applications of these devices in clinical trials and physiological studies.

The historical progression of EE assessment methodologies reveals a continuous evolution toward less invasive, more practical solutions. From the initial emergence of calorimeters in the late 18th century to the steady development of standardized equations throughout the 20th century, the field has now entered an intelligent era characterized by machine learning and computer vision applications [26]. This review examines the current state of integrating wearable EE data with established reference standards, providing researchers with a critical analysis of methodological approaches, accuracy assessments, and practical implementation frameworks.

Gold-Standard Measures for Energy Expenditure Validation

Established Reference Methodologies

Research validating wearable energy expenditure data relies on several established gold-standard measures, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Indirect Calorimetry: This method estimates energy expenditure by measuring oxygen consumption (VO₂) and carbon dioxide production (VCO₂) [27] [26]. It is considered one of the most accurate approaches for estimating EE because it directly reflects metabolic activity [27] [26]. Portable systems such as the PNOĒ metabolic analyzer enable measurements during physical activity, making them particularly valuable for validating wearable devices under controlled conditions [5].

Doubly Labelled Water (DLW) Technique: This approach uses stable isotopes to measure total daily energy expenditure over extended periods (typically 1-2 weeks) in free-living conditions [26]. While considered a gold standard for free-living total energy expenditure measurement, it is not suitable for assessing EE during single exercise sessions [26].

Direct Calorimetry: This method quantifies metabolic rate by precisely measuring heat loss through a calorimeter [26]. Although highly accurate, its application is limited by high costs, technical complexity, and the need for controlled laboratory conditions [26].

Comparative Framework for Validation Studies

When designing validation protocols, researchers should consider the appropriate reference standard based on the research question:

Table 1: Gold-Standard Methods for Energy Expenditure Validation

| Method | Primary Application | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect Calorimetry | Short-duration exercise validation | High accuracy for discrete activities; measures substrate utilization | Limited to controlled settings; equipment can be cumbersome |

| Doubly Labelled Water | Free-living total energy expenditure | Captures real-world activity patterns over time | Expensive; cannot provide exercise-specific data |

| Direct Calorimetry | Fundamental metabolic research | Considered the most accurate method | Highly specialized equipment; impractical for most validation studies |

Accuracy Assessment of Consumer Wearables

Quantitative Performance Across Metrics

Recent validation studies reveal significant variation in the accuracy of consumer wearables across different metrics. A comprehensive meta-analysis of 45 scientific studies examining commonly used fitness trackers found that these devices demonstrate markedly different performance levels depending on the metric being measured [4].

Table 2: Overall Accuracy of Fitness Trackers by Metric Type

| Metric | Average Accuracy | Performance Classification | Top Performing Device |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Rate | 76.35% | Strong | Apple Watch (86.31%) |

| Step Count | 68.75% | Moderate | Garmin (82.58%) |

| Energy Expenditure | 56.63% | Moderate | Apple Watch (71.02%) |

The overall cumulative accuracy across HR, SC, and EE metrics provided by analyzed fitness trackers is moderate, ranging between 62.09% and 73.53%, with an average score of 67.40% for accuracy [4]. This analysis highlights the particular challenge wearables face in measuring energy expenditure, a complex physiological process influenced by multiple individual factors.

Device-Specific Performance Analysis

Research comparing specific wearable devices against gold standards provides granular insights into their performance characteristics:

Apple Watch: In a meta-analysis of 56 studies, Apple Watches demonstrated a mean absolute percent error of 4.43% for heart rate and 8.17% for step counts, while the error for energy expenditure was significantly higher at 27.96% [2]. This inaccuracy was observed across all types of users and activities tested, including walking, running, cycling, and mixed-intensity workouts [2].

Archon Alive 001: A 2025 validation study comparing this affordable tracker (under $45) found it had a Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) of 3.46% for step count compared to manual hand tally, demonstrating high accuracy for this metric [5]. However, for total calorie expenditure, the device showed 29.3% MAPE relative to PNOĒ metabolic analyzer, indicating moderate accuracy for energy expenditure [5].

General Performance Trends: Newer wearable models generally show improved accuracy over earlier versions, with a "noticeable trend of gradual improvements over time" as manufacturers refine their sensors and algorithms [2]. However, the fundamental challenge of accurately estimating energy expenditure remains, with even the best-performing devices showing significant error margins compared to gold-standard measures.

Methodological Approaches for Integration and Validation

Experimental Protocols for Device Validation

Robust validation studies employ standardized protocols to assess wearable device performance under controlled conditions:

Treadmill Protocols: Studies typically have participants walk or run on treadmills at varying speeds (e.g., 3, 4, 5, and 8 km/h) while simultaneously wearing the consumer wearable and being connected to reference equipment such as portable gas analyzers [5]. Each stage typically lasts 3-5 minutes with rest intervals between stages to allow for equipment adjustments [5].

Comparative Metrics: Researchers calculate Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC), and Bland-Altman analysis to assess agreement between devices [5]. MAPE ≤3% is generally considered clinically irrelevant, providing a benchmark for acceptable performance [5].

Free-Living Validation: For assessing real-world performance, researchers combine doubly labelled water with wearable data collection over extended periods (typically 7-14 days) to capture a more comprehensive picture of device performance outside laboratory settings.

Emerging Technical Approaches

Recent research has explored innovative methods to enhance the accuracy of energy expenditure estimation:

Personalized Machine Learning Models: A 2025 study developed person-specific and group-level models using the Random Forest algorithm, analyzing 7 combinations of 4 biomarkers across 1 to 16 body locations [28]. Personalized models achieved significantly higher accuracy (2% MAPE) compared to generalized models (16.5%-28% MAPE) but were more sensitive to sensor placement and data availability [28].

Multi-Sensor Data Fusion: The highest accuracy in personalized EE prediction is achieved when combining movement-based, thermal, and cardiovascular data [28]. While accelerometry alone performs well, adding physiological inputs, particularly skin temperature, improves accuracy, especially for females [28].

Real-Time Energy Expenditure Estimation: The RTEE method integrates a Deep Q-Network-based activity intensity coefficient inference network with a modified energy consumption prediction algorithm to estimate energy expenditure based on real-time variations in the user's heart rate measurements [27]. This approach adapts conventional EE estimation formulas with a reinforcement learning component to improve real-time prediction accuracy.

The following diagram illustrates the typical experimental workflow for validating wearable energy expenditure data against gold-standard measures:

Experimental Validation Workflow for Wearable EE Data

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for EE Validation

Table 3: Essential Research Equipment for Wearable Validation Studies

| Equipment Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Metabolic Systems | PNOĒ metabolic analyzer, Douglas bag systems, Portable gas analyzers | Provides criterion measure for energy expenditure via indirect calorimetry | Measures oxygen consumption (VO₂) and carbon dioxide production (VCO₂) to calculate EE [5] |

| Research-Grade Accelerometers | Actigraph wGT3x-BT | Serves as intermediate standard for physical activity assessment | Validated 3-dimensional accelerometer commonly used in research settings [5] |

| Heart Rate Monitoring Systems | Polar OH1, Electrocardiogram systems | Provides validation standard for heart rate measurements | Photoplethysmography or ECG-based systems for comparison with wearable optical HR [5] |

| Calibration Equipment | Treadmills with calibrated speed settings, Flow sensors, Gas calibration kits | Ensures accuracy and standardization of measurement equipment | Provides controlled exercise intensities and calibrated gas flow measurements [5] |

| Data Analysis Platforms | ActiLife software, Custom MATLAB/Python scripts, Statistical packages | Processes and analyzes collected data for comparison | Enables calculation of MAPE, ICC, Bland-Altman analysis, and other validation metrics [5] |

The integration of wearable EE data with gold-standard measures reveals both opportunities and limitations for research applications. While consumer wearables demonstrate strong performance in measuring heart rate and moderate accuracy for step counting, their energy expenditure estimates show significantly higher error rates (27-30% MAPE) compared to reference standards [2] [5]. This indicates that while these devices can provide valuable general trends for population-level studies, their precision may be insufficient for clinical applications requiring high accuracy.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the strategic integration of wearable EE data should be guided by study objectives and precision requirements. Personalized models that combine multiple physiological signals show promise for improving accuracy but require more complex implementation [28]. Future directions should focus on developing standardized validation protocols, exploring hybrid modeling approaches that combine consumer wearables with brief gold-standard assessments, and addressing ethical considerations around data ownership and algorithm transparency as these technologies become more integrated into healthcare and clinical research [26].

The validation of energy expenditure (EE) algorithms in wearable technology represents a critical frontier in digital health. However, a significant accuracy gap persists for specific populations, particularly individuals with obesity, who exhibit distinct physiological and biomechanical characteristics [19] [29]. Current activity-monitoring algorithms, predominantly developed for and validated on populations without obesity, often fail to accurately reflect the physical activity and energy usage of people with higher body weight [19] [30]. This population stands to benefit immensely from physical activity trackers for health management, yet they are underserved by existing technology [31].

The inaccuracies stem from several factors specific to obesity. Individuals with obesity demonstrate known differences in walking gait, postural control, resting energy expenditure, and preferred walking speed compared to people without obesity [29]. Furthermore, hip-worn devices—often used in research settings—are prone to decreased accuracy due to biomechanical differences such as altered gait patterns and device tilt angle in people with obesity [29]. This case study examines the development and validation of a novel algorithm designed specifically to address these challenges and improve the accuracy of calorie tracking for individuals with obesity.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Energy Expenditure Algorithms

To objectively evaluate the landscape of algorithm performance, the following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent validation studies, including the novel population-specific algorithm developed by Northwestern University researchers.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Energy Expenditure Estimation Methods

| Algorithm/Device | Target Population | Validation Method | Key Performance Metric | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northwestern University BMI-Inclusive Algorithm [19] [29] | Individuals with obesity | Metabolic cart (in-lab); Wearable camera (free-living) | Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for METs; Overall Accuracy | RMSE: 0.281-0.32 METs; >95% accuracy in real-world situations |

| Archon Alive 001 (Affordable Tracker) [5] | General Population (BMI 18-25) | PNOĒ metabolic analyzer | Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) for Calorie Expenditure | 29.3% MAPE |

| Various Commercial Wrist-Worn Devices (Systematic Review) [32] | General Population | Multiple gold-standard methods | Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) for Energy Expenditure | MAPE >30% across all devices |

The data reveals a significant advancement represented by the Northwestern algorithm. While affordable commercial trackers like the Archon Alive and other wrist-worn devices show poor accuracy for energy expenditure (MAPE >29%), the population-specific model achieves a high level of precision, with an RMSE for Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET) estimation below 0.32 and overall accuracy exceeding 95% when validated against a metabolic cart [19] [5] [29]. This performance is particularly notable given that the algorithm was benchmarked against 11 state-of-the-art algorithms and demonstrated superior performance across various activity intensities [19] [29].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Algorithm Validation

The development and validation of the Northwestern algorithm involved a multi-stage, rigorous methodology that can serve as a model for future population-specific calibration research.

In-Lab Validation Protocol

This protocol was designed to collect high-fidelity data under controlled conditions [19] [29].

- Participant Profile: The study enrolled 27 participants (17 female) with obesity. Key demographic and health metrics were recorded.

- Sensor Configuration: Each participant was fitted with a Fossil Sport smartwatch (containing accelerometer and gyroscope sensors) on the wrist and an ActiGraph wGT3X+ activity monitor for comparative analysis.

- Gold-Standard Reference: Participants wore a metabolic cart during testing. This system measures the volume of oxygen inhaled and carbon dioxide exhaled to calculate energy burn in kilocalories (kCals) and resting metabolic rate with high precision [19].

- Activity Protocol: Participants engaged in a series of structured activities designed to capture a range of movement intensities (e.g., sedentary, light, moderate-to-vigorous). This created a paired dataset of sensor readings and ground-truth energy expenditure values.

- Data Processing: The raw sensor data from the smartwatch was used to build a machine learning model to estimate minute-by-minute MET values. The model's predictions were then compared to the MET values derived from the metabolic cart to calculate accuracy metrics like RMSE [29].

Free-Living Validation Protocol

To test the algorithm's performance in real-world settings, a second validation protocol was implemented [19] [29].

- Participant Profile: 25 participants (16 female) with obesity were enrolled.

- Sensor Configuration: Participants wore the study smartwatch and a body camera during their daily activities for two days.

- Validation Methodology: The body camera provided visual confirmation of physical activity, allowing researchers to identify specific instances where the algorithm's estimates of energy expenditure were inaccurate. This method enabled the team to pinpoint activities that caused over- or under-estimation of kCals [19] [31]. In total, 14,045 minutes of free-living data were analyzed.

- Performance Benchmarking: The algorithm's MET estimates in free-living conditions were compared to those from the top-performing actigraphy-based algorithm (Kerr et al.'s method). The new model's estimates fell within ±1.96 standard deviations of this benchmark for 95.03% of the minutes analyzed, demonstrating high concordance [29].

Diagram 1: Algorithm Validation Workflow

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Methods

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Validation Studies

| Item | Specification/Function | Application in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Cart | Measures O₂ inhaled and CO₂ exhaled via a mask. | Gold-standard method for calculating energy expenditure (kCals) and resting metabolic rate in lab settings [19]. |

| Research-Grade Accelerometer | ActiGraph wGT3X+ or wGT3X-BT. | Provides research-grade activity count data for benchmarking commercial device performance [5] [29]. |

| Wearable Camera | Body-worn device capturing first-person view. | Provides visual ground truth for activity type and context in free-living validation studies [19] [29]. |

| Portable Cardio-Metabolic Analyzer | PNOĒ system with Hans Rudolph mask. | Validates energy expenditure and heart rate by analyzing respiratory gases during exercise [5]. |

| Photoplethysmography Heart Rate Monitor | Polar OH1. | Provides validated heart rate data for benchmarking optical heart rate sensors in wearables [5]. |

| Open-Source Algorithm | Northwestern's model (open-source). | A transparent, rigorously testable algorithm that researchers can build upon for inclusive fitness tracking [19] [31]. |

Implications for Research and Clinical Practice

The development of population-specific algorithms marks a paradigm shift in wearable technology validation. The open-source nature of the Northwestern algorithm is particularly significant, as it provides a transparent, rigorously testable foundation that other researchers can replicate and build upon, addressing a critical gap in the field where most commercial algorithms remain proprietary [19] [29]. This approach enables the research community to advance the science of inclusive fitness tracking collectively.

From a clinical and public health perspective, accurate activity monitoring for individuals with obesity is crucial for tailoring effective interventions and improving health outcomes [19] [33]. Reliable data empowers healthcare professionals to design personalized programs and can accurately reflect the substantial effort exerted by individuals with obesity during physical activity, which is often underestimated by standard devices [19] [31] [30]. As one researcher noted, "Fitness shouldn't feel like a trap for the people who need it most" [19]. Future research should continue to explore population-specific calibrations across diverse groups and integrate these advanced algorithms into widely available commercial devices to maximize their public health impact.

The integration of wearable activity trackers into clinical trials represents a paradigm shift in how researchers monitor patient activity and energy balance outside traditional laboratory settings. These devices offer the potential for continuous, real-world data collection on key physiological parameters, enabling unprecedented insights into patient health and treatment outcomes. However, their utility is entirely dependent on the accuracy and reliability of the metrics they report. For clinical researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the specific strengths and limitations of these devices is critical for designing robust trials and interpreting resulting data. This guide provides an objective, evidence-based comparison of wearable device performance, focusing on the quantitative data and experimental protocols essential for their application in clinical research.

Quantitative Accuracy of Key Biometric Measurements

The validity of wearable data varies significantly by the type of metric being measured. The following tables summarize device performance for core parameters relevant to clinical trials, based on aggregated validation studies.

Accuracy of Core Activity and Energy Expenditure Metrics

Table 1: Accuracy of wearable devices for measuring activity and energy expenditure metrics. Error percentages are calculated against gold-standard reference methods (e.g., indirect calorimetry for energy expenditure, manually counted steps for step count).

| Device | Heart Rate (% Error) | Caloric Expenditure (% Error) | Step Count (% Error) | Sleep/Wake Identification (% Accuracy) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apple Watch | 1.3% (underestimation) [16] | 27.96% (MAPE*) [2]; Up to 115% [16] | 0.9-3.4% [16] | 97% (Sleep Onset) [16] |

| Oura Ring | 99.3% (Resting HR Accuracy) [16] | 13% [16] | 4.8%-50.3% [16] | 94% (Sleep Onset) [16] |

| WHOOP | 99.7% (Accuracy) [16] | N/A | N/A (Strain Metric Used) [16] | 90% (Sleep Onset) [16] |

| Garmin | 1.16-1.39% [16] | 6.1-42.9% [16] | 23.7% [16] | 98% (Sleep Onset) [16] |

| Fitbit | 9.3 BPM (underestimation) [16] | 14.8% [16] | 9.1-21.9% [16] | Overestimates Total Sleep Time [16] |

| Samsung | 7.1 BPM (underestimation) [16] | 9.1-20.8% [16] | 1.08-6.30% [16] | 65% (Sleep Stages) [16] |

| Polar | 2.2% (Upper Arm) [16] | 10-16.7% [16] | N/A | 92% (Sleep Onset) [16] |

MAPE: Mean Absolute Percentage Error

Accuracy in Disease and Medical Event Detection

For clinical trials focusing on specific disease outcomes, the ability of wearables to detect medical events is of paramount importance. Meta-analyses of real-world detection studies show promising results.

Table 2: Diagnostic accuracy of wearable devices for detecting medical conditions, as reported in systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

| Medical Condition | Pooled AUC (%) | Pooled Sensitivity (%) | Pooled Specificity (%) | Pooled PPV (%) | Key Devices Studied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 | 80.2 | 79.5 | 76.8 | N/A | Fitbit, Apple Watch, Oura Ring [34] |

| Atrial Fibrillation | N/A | 94.2 | 95.3 | 87.4 | Apple Watch, Others [34] |

| Fall Detection | N/A | 81.9 | 62.5 | N/A | Various [34] |

A systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating wearables for disease detection concluded that while these devices show promise, "further research and improvements are required to enhance their diagnostic precision and applicability" [34].

Experimental Protocols for Validating Wearable Metrics

The data presented above are derived from validation studies that employ rigorous methodologies to compare wearable device outputs against gold-standard references.

Protocol for Energy Expenditure (Caloric) Validation

- Objective: To assess the accuracy of a wearable device's estimate of total energy expenditure (kcal) and activity energy expenditure.

- Gold Standard Reference: Indirect calorimetry, typically using a portable metabolic cart (e.g., COSMED K5, VO2master) [35].

- Experimental Workflow:

- Participant Instrumentation: Participants are fitted with the gold-standard metabolic cart and the wearable device(s) under test.

- Baseline Measurement: Participants rest in a seated or supine position for 20-30 minutes to establish baseline resting energy expenditure.

- Structured Activity Protocol: Participants perform a series of activities of varying intensities in a controlled laboratory setting. A typical protocol includes:

- Sedentary tasks (e.g., typing, watching video)

- Light household chores (e.g., sweeping, tidying)

- Treadmill walking/running at multiple prescribed speeds (e.g., 3 km/h, 5 km/h, 8 km/h)

- Cycle ergometry at multiple prescribed power outputs (e.g., 50W, 100W, 150W)

- Data Synchronization: Timestamps from the wearable device and the metabolic cart are synchronized to align data streams for comparison.

- Data Analysis: The energy expenditure values from the wearable device are compared to the values from the metabolic cart across all activity stages and in aggregate. Statistical analyses include calculation of Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), Pearson correlation coefficients (r), and Bland-Altman plots to assess bias and limits of agreement [35] [2].

Protocol for Heart Rate and Heart Rate Variability (HRV) Validation

- Objective: To determine the accuracy of photoplethysmography (PPG)-based heart rate and HRV measurements.

- Gold Standard Reference: Electrocardiogram (ECG) [16] [35].

- Experimental Workflow:

- Participant Instrumentation: ECG electrodes are placed on the participant's chest in a standard configuration. The wearable device is worn according to manufacturer instructions (e.g., snug on the wrist).

- Controlled Resting Measurement: Participants rest quietly for 5-10 minutes while simultaneous ECG and PPG data are collected for resting heart rate and resting HRV (e.g., RMSSD) analysis.

- Ambulatory & Exercise Protocol: Participants engage in activities that introduce motion artifact, a key confounder for PPG. This includes:

- Walking and running on a treadmill

- Typing or performing arm movements while seated

- Functional strength training exercises [12]

- Data Processing: R-peaks are detected from the ECG signal to create a ground-truth tachogram. Pulse peaks are detected from the PPG signal. Inter-beat intervals (IBIs) are calculated from both.

- Data Analysis: Heart rate series from the wearable are compared to the ECG-derived heart rate. For HRV, time-domain (e.g., RMSSD, SDNN) and frequency-domain (e.g., LF, HF power) metrics from both sources are compared using correlation and error analysis [16].

Diagram 1: Wearable validation workflow.

Technical and Methodological Considerations for Clinical Trials

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Key equipment and tools required for validating and deploying wearables in clinical research.

| Item / Solution | Function in Research | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Gold-Standard Metabolic Cart | Measures oxygen consumption (VO₂) and carbon dioxide production (VCO₂) to calculate energy expenditure via indirect calorimetry. | COSMED K5, VO2master, Parvo Medics TrueOne |

| Electrocardiogram (ECG) System | Provides gold-standard measurement of heart rate and heart rate variability for validating optical heart rate sensors. | Biopac MP36R, ADInstruments PowerLab, Holter monitors |

| Actigraphy System | Research-grade motion sensor used as a higher-accuracy benchmark for activity and sleep/wake cycles. | ActiGraph wGT3X-BT, Axivity AX3 |

| Polysomnography (PSG) System | Comprehensive gold-standard for sleep staging (REM, NREM) and sleep quality assessment. | Compumedics Grael, Natus Sleepworks |

| Controlled Environment (Lab) | Standardizes external factors (temperature, humidity) and enables precise activity protocols. | Climate-controlled room, treadmills, cycle ergometers |

| Data Synchronization Software | Temporally aligns data streams from multiple devices (wearable, gold-standard) for precise comparison. | LabChart, AcqKnowledge, custom timestamp scripts |

Conceptual Framework for Clinical Trial Integration

Integrating wearables into a clinical trial requires a structured approach to ensure data quality and relevance.

Diagram 2: Clinical trial integration flow.

The evidence demonstrates a clear hierarchy in the accuracy of wearable metrics. Heart rate is generally the most accurately measured parameter, especially at rest, with many devices achieving error rates below 5% [16] [2]. In contrast, energy expenditure (caloric burn) remains a significant challenge, with even the best devices showing mean absolute percentage errors often exceeding 25% due to the complex physiological modeling required and individual variability [35] [2]. Step counts are reasonably accurate during steady-state walking but can be highly inaccurate during intermittent activities or upper-body movement [16].

For clinical trial application, this means:

- Device Selection Must Be Endpoint-Specific: Wearables are well-suited for trials where relative changes in activity (e.g., step count) or robust heart rate monitoring are primary endpoints. They are less suitable for trials requiring precise, absolute measurements of energy balance.

- Validation is Crucial: Before deployment in a trial, the specific device and model should be validated against a gold standard for the target population and activities relevant to the study.

- Focus on Trends, Not Absolute Values: The longitudinal tracking capability of wearables is one of their greatest strengths. Analyzing within-participant trends over time can be more reliable and clinically meaningful than interpreting single-point absolute values.