The Gut Microbiota Metabolome: Mechanisms and Applications of Bioactive Food Compound Transformation in Human Health and Disease

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the bidirectional interactions between the gut microbiota and dietary bioactive compounds, a critical frontier in nutritional science and therapeutic development.

The Gut Microbiota Metabolome: Mechanisms and Applications of Bioactive Food Compound Transformation in Human Health and Disease

Abstract

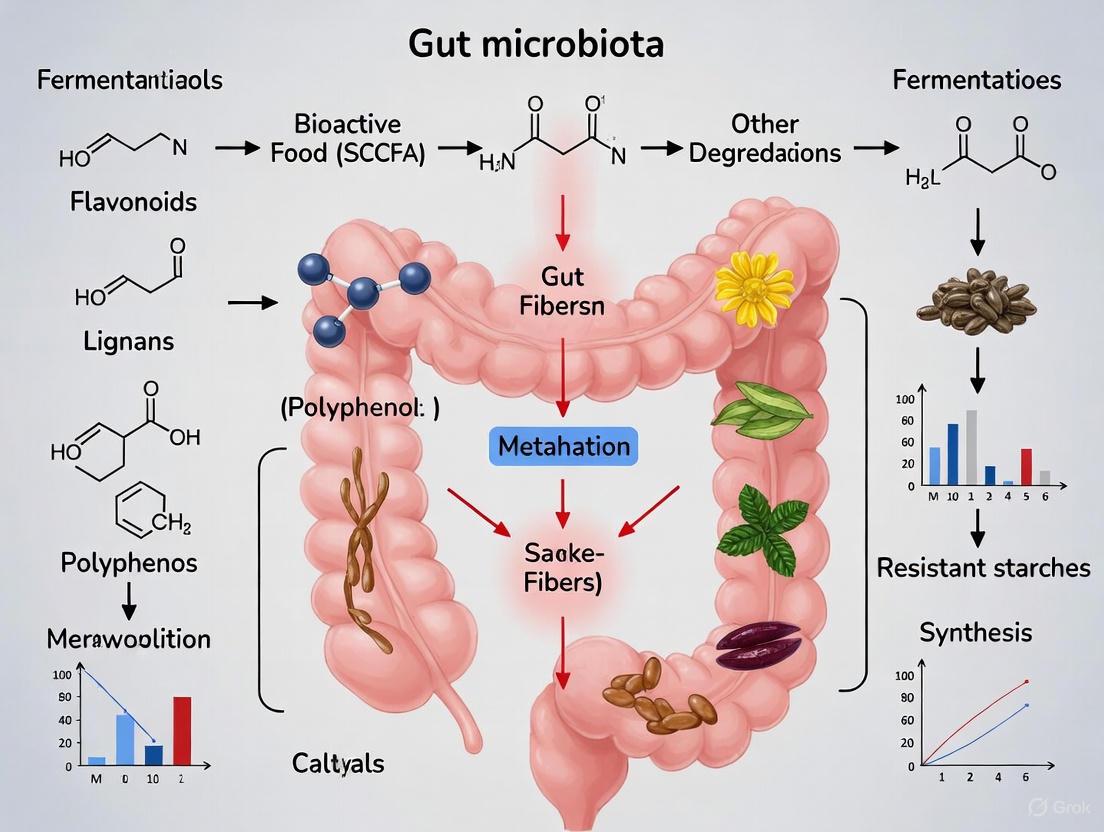

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the bidirectional interactions between the gut microbiota and dietary bioactive compounds, a critical frontier in nutritional science and therapeutic development. We explore the foundational mechanisms by which gut microbial consortia metabolize fibers, polyphenols, proteins, and lipids into key bioactive metabolites like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), indole derivatives, and secondary bile acids. For researchers and drug development professionals, we detail advanced methodological approaches including in vitro models, multi-omics integration, and synthetic biology, alongside applications in metabolic health, immunomodulation, and neurological function. The content addresses current research challenges in clinical validation and standardization while evaluating microbiome-based diagnostics against conventional biomarkers. This synthesis establishes the gut microbiota as a transformative target for precision nutrition and next-generation functional food development.

Unraveling Core Mechanisms: How Gut Microbiota Transform Dietary Bioactives into Key Metabolites

The human gastrointestinal tract hosts a complex and dynamic ecosystem, the gut microbiota, which constitutes a vital metabolic "organ" interfacing with host physiology. This community of bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses encodes over 3 million genes—a genomic repertoire 150-fold larger than the human genome—enabling extensive metabolic capabilities that the host has not evolved [1]. The concept of the gut as a metabolic interface has emerged from the understanding that this microbial consortium is not a passive passenger but an active participant in regulating host metabolism, immune function, and neurological signaling. Within the context of bioactive food compound research, this interface represents the critical site where dietary components are biotransformed into health-modulating metabolites, governing systemic physiological outcomes through a network of gut-organ axes [2] [3]. The symbiotic relationship between host and microbiota is fundamental to health, with dysbiosis—a disruption in microbial community structure and function—implicated in the pathogenesis of numerous conditions, including metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative disorders, and immune dysregulation [4] [1].

This whitepaper provides a comprehensive overview of the mechanisms underpinning host-microbe symbiosis at this metabolic interface. It synthesizes current research on how dietary bioactives are processed by gut microbial networks to produce effector molecules that influence host physiology distally. We further detail cutting-edge experimental models and analytical frameworks, such as genome-scale metabolic modeling (GEMs), that are advancing our capacity to decode the complexity of these interactions and accelerate the development of microbiome-targeted therapeutic and nutritional interventions [5].

Core Mechanisms of Host-Microbe Metabolic Symbiosis

The metabolic symbiosis at the gut interface is facilitated by a continuous molecular dialogue, wherein host-derived and dietary compounds are metabolized by the microbiota into a diverse array of signaling molecules and metabolites. These microbial products are essential for maintaining host homeostasis and form the mechanistic basis of the gut-X axes.

Key Microbial Metabolites and Their Systemic Roles

- Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs): Produced by the bacterial fermentation of dietary fibers, SCFAs like acetate, propionate, and butyrate are among the most well-characterized microbial metabolites. Butyrate serves as a primary energy source for colonocytes and reinforces intestinal barrier integrity by upregulating tight junction proteins [2]. Propionate is primarily involved in gluconeogenesis in the liver, while acetate enters the peripheral circulation to influence lipid metabolism and immune responses. SCFAs also act as histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, thereby exerting epigenetic regulation on host gene expression [1].

- Trimethylamine-N-Oxide (TMAO): Derived from the microbial metabolism of dietary choline and L-carnitine (abundant in red meat), TMAO is a well-established biomarker and promoter of atherosclerosis pathogenesis. Its production exemplifies how dietary intake can shape microbiota function to influence cardiovascular health [1].

- Secondary Bile Acids: Primary bile acids synthesized by the host liver can be modified by gut bacteria into secondary bile acids. These metabolites act as signaling molecules through host receptors such as the Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR) and G-protein-coupled bile acid receptor 1 (TGR5), regulating not only their own synthesis but also glucose and lipid metabolism [1].

- Indoles and Tryptophan Metabolites: Tryptophan from the diet can be metabolized by host enzymes, gut microbes, or both. Microbial metabolites, including indole and its derivatives, influence intestinal barrier function and immune homeostasis by activating the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) and modulating inflammation [3].

The Network of Gut-Organ Axes

The systemic effects of microbial metabolites are mediated through specific gut-organ axes, forming an integrated communication network:

- Gut-Liver-Adipose Axis: The liver and adipose tissue are key metabolic organs directly influenced by gut-derived metabolites. Research using advanced in vitro models has demonstrated that specific probiotic and prebiotic combinations can synergistically reduce hepatic lipid accumulation and activate thermogenic pathways in adipocytes, highlighting the therapeutic potential of targeting this axis for metabolic syndrome [2].

- Gut-Brain Axis: A bidirectional communication pathway linking the enteric nervous system with the central nervous system. Microbial metabolites like SCFAs, as well as neurotransmitters produced by bacteria, can signal to the brain via neural, endocrine, and immune pathways. Alterations in this axis are implicated in the pathophysiology of Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease [1].

- Gut-Muscle Axis (Gut-Muscle Axis): Emerging evidence indicates a role for the gut microbiota in musculoskeletal health. Gut dysbiosis can drive systemic inflammation, accelerating muscle protein degradation in sarcopenia. Conversely, SCFA-producing taxa (e.g., Roseburia, Eubacterium) may enhance mitochondrial function and muscle mass [1].

Table 1: Key Microbial Metabolites and Their Physiological Roles

| Metabolite | Dietary Precursor | Producing Taxa (Examples) | Primary Physiological Roles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Butyrate | Dietary Fiber | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia | Colonocyte energy, barrier integrity, HDAC inhibition |

| TMAO | Choline, L-Carnitine | --- | Promotes atherosclerosis, cardiovascular risk |

| Secondary Bile Acids | Primary Bile Acids | --- | FXR/TGR5 signaling, glucose & lipid metabolism |

| Indoles | Tryptophan | --- | AhR activation, immune & barrier regulation |

Methodologies for Investigating Host-Microbe Interactions

Deciphering the complexity of the gut metabolic interface requires a multi-faceted research approach, combining sophisticated in vitro and in vivo models with powerful computational frameworks.

Experimental Models and Protocols

In Vitro Gut-Liver-Adipose Axis Model

A cornerstone methodology for investigating multi-organ interactions without the use of animal models.

- Protocol Overview: This innovative model employs a Transwell co-culture system to house human cell lines representing the intestinal epithelium (Caco-2), liver (HepG2), and adipose tissue (3T3-L1) [2].

- Experimental Workflow:

- Co-culture Establishment: The three cell lines are cultured in a layered configuration that allows for the exchange of soluble mediators, mimicking physiological crosstalk.

- Intervention: The system is treated with a combination of specific probiotics (e.g., Bifidobacterium bifidum GM-25, B. infantis GM-21, Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GM-28) and polycosanols.

- Outcome Assessment:

- Intestinal Barrier: Measure Trans-epithelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) and tight junction protein (e.g., occludin, ZO-1) expression in Caco-2 cells.

- Hepatic Lipid Metabolism: Analyze genes and proteins involved in lipid accumulation (e.g., CD36, SREBP-1, PPARγ, AMPK) in HepG2 cells.

- Adipocyte Thermogenesis: Assess activation of thermogenic pathways via UCP1 and PGC-1α levels in 3T3-L1 cells [2].

In Vivo Assessment of Bioactive Compounds

Animal models remain essential for validating the systemic effects of dietary bioactives and probiotics.

- Protocol for Evaluating Hypoglycemic Competence of Polysaccharides:

- Animal Model: Use type 2 diabetic mice (e.g., induced by high-fat diet and streptozotocin).

- Intervention: Administer a defined polysaccharide, such as low molecular weight polysaccharides from Laminaria japonica (LJOO), over a set period.

- Outcome Measures:

- Host Physiology: Monitor fasting blood glucose and insulin levels.

- Microbiota Analysis: Collect cecal or fecal contents for 16S rRNA gene sequencing to assess changes in microbial diversity (e.g., Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio) and abundance of SCFA producers (e.g., Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium).

- Metabolite Profiling: Quantify cecal SCFA levels using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) to link microbial shifts to functional outcomes [2].

Computational and Analytical Frameworks

Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs)

GEMs are powerful computational tools that simulate the metabolic network of an organism or community.

- Application: GEMs enable the exploration of metabolic interdependencies and cross-feeding relationships between the host and its microbiota. By simulating metabolic fluxes, researchers can predict how dietary inputs or microbial perturbations affect community function and host metabolic health [5].

- Workflow: The process involves reconstructing a metabolic network from genomic data, integrating experimental constraints (e.g., transcriptomics, metabolomics), and using constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) methods to simulate metabolic behavior under different conditions [5].

Longitudinal Microbiota Analysis in Cohorts

Large-scale longitudinal studies in human cohorts are critical for defining healthy microbiota development and its association with long-term health.

- The Gut Microbiota Wellbeing Index: A recent study of nearly 1000 infants analyzed over 6200 fecal samples to define gut microbiota development trajectories. The research demonstrated that microbiota succession is highly predictable and that deviations from a healthy trajectory (dysbiosis) are associated with adverse health outcomes. This allowed for the creation of an index where specific early-life keystone organisms, such as Bifidobacterium and Bacteroides, consistently predicted positive health outcomes over the first five years of life [6].

Table 2: Core Analytical Techniques in Gut Microbiota Research

| Technique | Application | Key Outputs | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Sequencing | Profiling microbial community structure | Taxonomic diversity, relative abundance | Cost-effective; limited functional insight |

| Shotgun Metagenomics | Profiling entire microbial gene content | Functional potential, taxonomic resolution to species level | More expensive; reveals metabolic pathways |

| Metatranscriptomics | Assessing active microbial gene expression | Gene expression profiles, active pathways | Captures real-time activity; technically complex |

| Metabolomics | Quantifying small molecule metabolites | SCFA, TMAO, bile acid levels | Direct functional readout; challenging to link to producers |

| Genome-Scale Modeling (GEMs) | Predicting metabolic fluxes & interactions | In silico simulation of diet/microbe interactions | Hypothesis-generating; requires high-quality data |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents used in the featured experiments and broader research on host-microbe symbiosis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating the Gut-Metabolic Interface

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line | Model of human intestinal epithelium; assesses barrier integrity & transport | Measuring TEER and tight junction expression in co-culture models [2] |

| HepG2 Cell Line | Model of human hepatocyte function; studies hepatic glucose & lipid metabolism | Analyzing reduction in lipid accumulation (e.g., CD36, SREBP-1 modulation) [2] |

| 3T3-L1 Cell Line | Model of adipocyte differentiation & function; studies energy storage & thermogenesis | Quantifying activation of thermogenic markers (UCP1, PGC-1α) [2] |

| Transwell Co-culture Systems | Permits soluble crosstalk between different cell types in a compartmentalized setup | Establishing the in vitro gut-liver-adipose axis model [2] |

| Defined Probiotic Strains | Used as interventions to modulate gut microbiota composition and host physiology | Bifidobacterium bifidum GM-25, B. infantis GM-21, Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GM-28 [2] |

| Specific Bioactive Polysaccharides | Purified dietary fibers used to probe microbial metabolic functions and host effects | Low molecular weight polysaccharides from Laminaria japonica (LJOO) for hypoglycemic studies [2] |

| Germ-Free or Gnotobiotic Mice | Animals devoid of microbiota or colonized with defined microbial consortia; establishes causality | Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) from hypertensive or diseased donors to test causality [1] |

Signaling Pathways Modulated by Microbial Metabolites

The systemic effects of microbial metabolites are mediated through the modulation of key host signaling pathways. The following diagram synthesizes the primary pathways discussed, illustrating how dietary inputs are transformed into signals that regulate the gut-liver-adipose axis.

Future Directions and Translational Potential

The field of host-microbe symbiosis research is rapidly evolving, with several key challenges and opportunities on the horizon. A primary challenge is the limited clinical validation of findings from preclinical models, necessitating well-designed human trials that link microbial biomarkers to tangible health outcomes [2]. Furthermore, the synergistic effects of multiple food components present a vast, underexplored frontier for developing more effective nutritional interventions; the combination of specific polysaccharides and probiotics, for instance, has shown enhanced anti-aging and antioxidant effects in model organisms, suggesting powerful synergies [2] [3]. To overcome these hurdles, future research must prioritize the integration of multi-omics data through advanced computational frameworks like GEMs and artificial intelligence, enabling predictive bioactivity modeling and personalized nutritional recommendations [2] [5]. Finally, the development of targeted delivery systems, such as microencapsulation, will be crucial to ensure the efficacy of probiotics and bioactive compounds as they transit through the gastrointestinal tract [2]. The continued unraveling of the gut's role as a metabolic interface holds immense promise for the development of next-generation functional foods and microbiome-based therapeutics for metabolic, immune, and age-related diseases.

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) represent the major carbon flux from the diet through the gut microbiome to the host, serving as crucial signaling molecules in the intricate cross-talk between gut microbiota and human physiology [7]. These microbial metabolites, primarily acetate, propionate, and butyrate, are the end products of the anaerobic fermentation of non-digestible carbohydrates (NDC) that escape digestion and absorption in the small intestine [7] [8]. The discovery that SCFAs serve as natural ligands for free fatty acid receptors (FFAR2/3, GPR109A) found on diverse cell types has generated renewed interest in their role in human health and disease [7] [9]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical overview of SCFA production pathways, their regulatory mechanisms, and analytical methodologies relevant to drug development and biomedical research.

Core Production Pathways and Microbial Taxa

Biochemical Pathways of SCFA Formation

SCFA production occurs primarily through saccharolytic fermentation, with distinct biochemical pathways leading to each major SCFA:

Acetate Production: Primarily through acetyl-CoA derived from glycolysis, with acetate production pathways widely distributed among numerous bacterial groups [7] [9]. Acetate can also be enzymatically converted to butyrate via butyryl-CoA:acetyl-CoA transferase [9].

Propionate Production: Occurs primarily through the succinate pathway during glycolysis, as indicated by the widespread distribution of the methylmalonyl-CoA decarboxylase (mmdA) gene in Bacteroidetes and many Negativicutes [9]. Deoxy-sugars (fucose, rhamnose) are particularly propiogenic due to metabolic pathways present to reduce the carbon skeleton via the intermediate 1,2-propanediol in select organisms [7].

Butyrate Production: Derived from carbohydrate fermentation via glycolysis through the combination of two acetyl-CoA molecules to form acetoacetyl-CoA, followed by stepwise reduction to butyryl-CoA [9]. The final step occurs via two different approaches: the butyryl-CoA:acetate CoA-transferase route or the phospho-butyrate and butyrate kinase pathways [9].

Table 1: Primary SCFA Production Pathways and Key Characteristics

| SCFA | Primary Pathway | Key Enzymes | Molar Ratio | Production Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate | Glycolysis via acetyl-CoA | Butyryl-CoA:acetyl-CoA transferase | ~60% | Proximal colon |

| Propionate | Succinate pathway | Methylmalonyl-CoA decarboxylase | ~20% | Throughout colon |

| Butyrate | Acetyl-CoA condensation | Butyryl-CoA:acetate CoA-transferase | ~20% | Distal colon |

SCFA-Producing Microorganisms

The production of SCFAs is characterized by significant functional specialization among gut microbial taxa:

Acetate Producers: Akkermansia muciniphila, Bacteroides spp., and numerous other bacterial groups possess widely distributed acetate production pathways [9].

Propionate Producers: Dominated by relatively few bacterial genera, including Bacteroides, Akkermansia muciniphila, and Roseburia inulinivorans [7] [9]. Species such as Akkermansia muciniphila have been identified as key propionate-producing mucin-degrading organisms [7].

Butyrate Producers: A surprisingly small number of organisms dominate butyrate production, including Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Eubacterium rectale, Eubacterium hallii, and Ruminococcus bromii [7] [10] [9]. Fermentation of resistant starch is particularly dependent on Ruminococcus bromii, whose absence significantly reduces resistant starch fermentation [7].

Table 2: Key SCFA-Producing Bacterial Taxa and Their Substrate Preferences

| Bacterial Taxon | Phylum | Primary SCFA | Preferred Substrates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Akkermansia muciniphila | Verrucomicrobia | Acetate, Propionate | Mucin |

| Bacteroides spp. | Bacteroidetes | Acetate, Propionate | Diverse polysaccharides |

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | Firmicutes | Butyrate | Resistant starch, dietary fibers |

| Eubacterium rectale | Firmicutes | Butyrate | Resistant starch |

| Ruminococcus bromii | Firmicutes | Butyrate | Resistant starch |

| Roseburia inulinivorans | Firmicutes | Propionate | Inulin, diverse fibers |

Molecular Mechanisms of SCFA Signaling and Function

Receptor-Mediated Signaling Pathways

SCFAs exert their physiological effects primarily through two fundamental mechanisms: receptor-mediated signaling and epigenetic regulation:

G Protein-Coupled Receptor (GPCR) Activation:

- FFAR2 (GPR43): Preferentially activated by acetate, modulating immune responses through regulation of neutrophil chemotaxis, reactive oxygen species production, and cytokine expression [10] [9].

- FFAR3 (GPR41): Primarily activated by propionate, influencing metabolic functions including enteroendocrine hormone secretion and energy homeostasis [10] [11].

- GPR109A: Activated by butyrate, contributing to anti-inflammatory signaling and immune cell differentiation, particularly in the maintenance of colonic regulatory T cells [10] [9].

Epigenetic Mechanisms

Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) Inhibition:

- SCFAs, particularly butyrate, function as potent HDAC inhibitors, leading to histone hyperacetylation and altered gene expression patterns [9].

- This mechanism regulates fundamental cellular processes including proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, with significant implications for inflammatory diseases and cancer [9].

- HDAC inhibition represents a crucial pathway through which microbial metabolites directly influence host epigenetic regulation [9].

Quantitative Aspects of SCFA Production and Distribution

Production Rates and Physiological Concentrations

The human colon produces approximately 500-600 mmol of SCFAs daily, with significant variation depending on dietary fiber intake, microbiota composition, and gut transit time [8]. The molar ratio of acetate to propionate to butyrate is approximately 60:20:20 in the human colon and feces, though this varies by colonic region and dietary factors [8] [9].

Table 3: SCFA Production and Distribution in Humans

| Parameter | Acetate | Propionate | Butyrate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Production | 300-360 mmol | 100-120 mmol | 100-120 mmol |

| Colonic Lumen Concentration | 60-80 mM | 20-30 mM | 10-20 mM |

| Peripheral Circulation | 50-150 μM | 1-5 μM | 1-5 μM |

| Primary Production Site | Proximal colon | Throughout colon | Distal colon |

| Major Metabolic Fate | Peripheral tissue metabolism | Hepatic gluconeogenesis | Colonocyte energy |

Biological Gradient and Tissue-Specific Exposure

A significant biological gradient exists for SCFAs from the gut lumen to the periphery, creating differential exposure across tissues:

- Colonic Lumen: Highest concentrations (millimolar range) with butyrate serving as the preferred energy source for colonocytes [7].

- Portal Circulation: Moderate concentrations, with significant hepatic extraction of propionate and butyrate [7].

- Systemic Circulation: Lowest concentrations (micromolar range), with acetate representing approximately 75% of total peripheral SCFAs due to limited hepatic extraction [7] [12].

This gradient means that SCFAs function as local signaling molecules in the gut while exerting endocrine effects at distant sites, with varying biological impacts depending on the tissue and concentration [7].

Analytical Methodologies for SCFA Quantification

Sample Preparation and Extraction

Accurate quantification of SCFAs in biological matrices requires specialized sample pretreatment:

- Sample Types: Feces, serum, plasma, tissues, and in vitro fermentation samples [13].

- Extraction Methods: Liquid-liquid extraction, solid-phase extraction, and acidification to protonate SCFAs for improved recovery [13].

- Stabilization: Immediate freezing at -80°C and acid preservation to prevent continued microbial fermentation ex vivo [13].

Separation and Detection Platforms

Advanced analytical approaches for SCFA quantification include:

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS): Provides high sensitivity and resolution for SCFA separation, often requiring derivatization to improve volatility [13].

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS): Enables direct analysis without derivatization, with emerging hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) methods improving retention of polar SCFAs [13].

- Capillary Electrophoresis (CE): Alternative separation technique offering high efficiency with minimal sample requirements [13].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Provides structural information and absolute quantification without separation, though with lower sensitivity than MS-based methods [14].

Experimental Models and Research Tools

In Vivo Modulation Approaches

Table 4: Research Models for Investigating SCFA Production and Function

| Model System | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Trials | Dose-response relationships, Biomarker identification | Physiological relevance, Clinical translation | Limited mechanistic insight, High inter-individual variability |

| Gnotobiotic Mice | Microbial causality, Host-microbe interactions | Controlled microbiota, Genetic manipulation possible | Artificial systems, Limited microbial diversity |

| Antibiotic Depletion [15] | Microbiome function, SCFA supplementation studies | Established protocol, Rapid depletion | Off-target effects, Non-specific depletion |

| In Vitro Fermentation | Metabolic pathways, Substrate utilization | High throughput, Controlled conditions | Simplified system, Lacks host components |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 5: Key Research Reagents for SCFA Investigations

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCFA Receptor Modulators | FFAR2/3 agonists (4-CMTB), antagonists (CATPB) | Receptor mechanism studies | Target validation, Signaling pathway elucidation |

| HDAC Inhibitors | Sodium butyrate, Trichostatin A | Epigenetic mechanism studies | HDAC inhibition controls, Specificity profiling |

| Microbial Inhibitors | Neomycin, Vancomycin, Bacitracin [15] | Microbiome depletion models | Specific taxon inhibition, Community manipulation |

| SCFA Supplementation | Sodium acetate, Sodium butyrate, Sodium propionate [15] | Functional restoration studies | Physiological level repletion, Dose-response studies |

| Transport Inhibitors | MCT1 inhibitors (AZD3965) | Cellular uptake studies | Transporter function, Tissue-specific targeting |

| Stable Isotope Tracers | 13C-acetate, 13C-butyrate | Metabolic flux analysis | Production rate quantification, Tissue distribution |

Implications for Drug Development and Therapeutic Applications

The multifaceted roles of SCFAs in human physiology position them as attractive targets for therapeutic intervention:

- Metabolic Diseases: SCFAs regulate glucose homeostasis through stimulation of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) secretion and improvement of insulin sensitivity [7] [9].

- Neurological Disorders: SCFAs modulate microglial function, blood-brain barrier integrity, and neuroinflammation, with implications for Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and autism spectrum disorders [8] [10].

- Inflammatory Conditions: Through regulation of Treg differentiation and anti-inflammatory cytokine production, SCFAs demonstrate therapeutic potential in inflammatory bowel disease, arthritis, and other immune-mediated disorders [10] [9].

- Oncological Applications: SCFAs, particularly butyrate, inhibit cancer cell proliferation and induce apoptosis through HDAC inhibition, with promising applications in colorectal cancer prevention and treatment [13] [9].

SCFAs represent crucial mechanistic links between dietary patterns, gut microbiota composition, and host physiological outcomes. Their production through microbial fermentation of dietary fibers and resistant starches illustrates the profound functional importance of the gut microbiome in human metabolism and disease susceptibility. Future research priorities include developing more precise analytical methods for in vivo SCFA flux quantification, elucidating individual genetic factors influencing SCFA responsiveness, and translating microbiome-based interventions into clinically validated therapies. As drug development increasingly recognizes the importance of host-microbiome interactions, SCFA pathways offer promising targets for novel therapeutic strategies across a spectrum of metabolic, inflammatory, and neurological conditions.

Dietary polyphenols, a diverse class of plant-secondary metabolites, have attracted significant scientific interest due to their potential health benefits, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective properties [16] [17]. However, their bioavailability is notoriously low, with only 5-10% of ingested polyphenols absorbed in the small intestine [18] [19]. The remaining 90-95% transit to the colon, where the gut microbiota performs an indispensable role in transforming these complex compounds into bioavailable and often more bioactive metabolites [20] [18] [17]. This biotransformation process, primarily comprising deconjugation, ring fission, and bioactivation, is a critical determinant of the physiological effects of dietary polyphenols. Understanding these microbial-mediated processes is fundamental to research on gut microbiota metabolism of bioactive food compounds, as the resulting metabolites act as key mediators in the diet-microbiota-host axis, influencing immune, metabolic, and neurological pathways [16].

Core Processes of Microbial Biotransformation

The structural complexity of dietary polyphenols necessitates extensive modification before systemic absorption and activity. The gut microbiota facilitates this through a series of enzymatic reactions.

Deconjugation

Most polyphenols exist in food matrices as glycosides, esters, or polymers. Deconjugation is the initial step in their catabolism.

- Mechanism: Glycosidases, esterases, and glucuronidases produced by colonic bacteria hydrolyze sugar moieties, ester bonds, and glucuronide conjugates, releasing aglycones and simpler phenolic acids [20] [19]. Lactase-phlorizin hydrolase (LPH) on the brush border of small intestinal epithelial cells can also deglycosylate some polyphenols [20] [17].

- Microbial Involvement: Bacterial populations across phyla such as Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria possess broad O-glycosidase and C-glycosidase activities [20]. Specific bacteria, including E. coli, Bifidobacterium, and Lactobacillus, are known to participate in these hydrolytic processes [19].

- Significance: Deconjugation is a prerequisite for absorption and further microbial ring fission, as aglycones are more lipophilic and accessible to bacterial enzymes [17].

Ring Fission

Following deconjugation, the aromatic rings of the polyphenol aglycones are cleaved. This is a hallmark of microbial catabolism.

- Mechanism: The heterocyclic C-rings of flavonoids and the aromatic rings of non-flavonoids are cleaved by specific microbial enzymes, producing smaller, low-molecular-weight phenolic catabolites [21] [16] [17].

- Products: Typical ring fission catabolites (RFCs) include various phenolic acids, phenylvalerolactones, phenylvaleric acids, and urolithins [21] [16]. For instance, flavan-3-ols from tea and cocoa are converted to phenyl-γ-valerolactones, while ellagitannins yield urolithins [16] [17].

- Significance: Ring fission generates metabolites that are more easily absorbed and frequently exhibit greater bioactivity than their parent compounds [16].

Bioactivation

Biotransformation is not merely a degradative process; it is a crucial mechanism for bioactivation.

- Definition: Bioactivation refers to the microbial or host enzymatic transformations that convert dietary precursors into metabolites with enhanced or novel biological activities [20] [16].

- Examples:

- The simple phenol tyrosol, found in olive oil, is bioactivated by human cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP2A6 and CYP2D6) to hydroxytyrosol, a potent antioxidant [20].

- The plant lignan secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG) is converted by gut microbiota to the mammalian lignans enterodiol and enterolactone, which possess phytoestrogenic and anticancer properties [16].

- Resveratrol is reduced to dihydroresveratrol, which may have enhanced bioactivity [16].

- Significance: The health effects associated with polyphenol-rich diets are often attributable to these microbially derived bioactive metabolites rather than the native compounds [20] [16].

Table 1: Key Microbial Metabolites and Their Parent Polyphenols

| Parent Polyphenol | Class | Key Microbial Metabolites | Notable Bioactivities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proanthocyanidins (Condensed Tannins) | Flavan-3-ol polymers | Phenyl-γ-valerolactones, Phenylvaleric Acids, Phenolic Acids (e.g., 5-(3',4'-Dihydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone) | Antioxidant, Cardioprotective, Neuroprotective [16] [17] |

| Ellagitannins (Hydrolysable Tannins) | Gallic acid/Hexahydroxydiphenoyl esters | Urolithins (A, B, C, D, etc.) | Anti-inflammatory, Anticancer, Anti-aging, Neuroprotective [16] [17] |

| Resveratrol | Stilbene | Dihydroresveratrol, Lunularin | Potentiated Antioxidant and Neuroprotective effects [16] |

| Secoisolariciresinol Diglucoside (SDG) | Lignan | Enterodiol, Enterolactone | Phytoestrogenic, Anticancer (hormone-dependent), Antioxidant [16] |

| Isoflavones (e.g., Daidzin) | Flavonoid | Equol, O-Desmethylangolensin (O-DMA) | Estrogenic/Anti-estrogenic, Bone health promotion [18] |

Table 2: Quantitative Profile of Select Polyphenol Metabolites in Humans

| Metabolite | Parent Compound | Peak Plasma Concentration (C~max~) | Time to C~max~ (T~max~) | Apparent Elimination Half-Life (AT~1/2~) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urolithin A glucuronide | Ellagitannins (from Pomegranate, Berries) | ~5–20 µM | 24–48 hours | > 24 hours [21] |

| Dihydroresveratrol sulfate | Resveratrol (from Grapes, Red Wine) | ~1–5 µM | 8–12 hours | ~10 hours [21] |

| 5-(3',4'-Dihydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone | Flavan-3-ols (from Tea, Cocoa) | ~0.1–1 µM | 6–10 hours | ~5 hours [21] |

| Enterolactone glucuronide | Lignans (from Flaxseed, Sesame) | ~10–100 nM | 24–36 hours | > 24 hours [21] |

| Hydroxytyrosol sulfate | Tyrosol/Oleuropein (from Olive Oil) | Low nM range (Metabolites 50-100x higher) | 1–2 hours | Not Specified [20] |

Experimental Protocols for Studying Biotransformation

Research into polyphenol biotransformation relies on a combination of in vitro and in vivo models to elucidate metabolic pathways and quantify metabolites.

In Vitro Fecal Fermentation Models

This protocol simulates the colonic environment to study the microbial metabolism of polyphenols.

Detailed Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Collect fresh fecal samples from healthy human volunteers, ensuring ethical approval. Pool samples from multiple donors to represent microbial diversity or use individual samples to study inter-individual variability.

- Inoculum Preparation: Immediately dilute the fecal sample in an anaerobic, pre-reduced phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.0) or specific culture medium like YCFA (Yeast Extract-Casein Hydrolysate-Fatty Acids). Homogenize under a constant stream of CO₂ or N₂ to maintain anaerobiosis.

- Fermentation Setup: Combine the fecal inoculum (e.g., 10% v/v) with a polyphenol substrate (e.g., purified compound or plant extract) in a sealed fermentation vessel. Include controls without substrate and without inoculum.

- Incubation: Incubate the vessels anaerobically at 37°C with constant agitation for a period ranging from 0 to 72 hours.

- Sampling: Collect aliquots at predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 6, 12, 24, 48 h). Centrifuge immediately to separate microbial cells from the supernatant.

- Analysis:

- Metabolite Profiling: Analyze the supernatant using Liquid Chromatography coupled with Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS). Use High-Resolution MS (HR-MS) for untargeted metabolite identification and Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) for targeted quantification of known catabolites [21].

- Microbial Analysis: Extract genomic DNA from the pellet for 16S rRNA gene sequencing to track changes in microbial community structure. Alternatively, use quantitative PCR (qPCR) to quantify specific bacterial taxa.

Protocol for Profiling Phenolic Catabolites in Biofluids

This protocol is for identifying and quantifying polyphenol metabolites in plasma and urine from human or animal intervention studies.

Detailed Methodology:

- Study Design: Conduct a controlled intervention study with a defined dose of polyphenol (e.g., 250 mg resveratrol, 1 cup of green tea). Implement a washout period and control diet low in polyphenols prior to the study.

- Sample Collection: Collect blood (e.g., pre-dose, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 24, 48 h post-dose) and urine (e.g., pre-dose, 0-24 h, 24-48 h collections). Process plasma by centrifugation and store all biofluids at -80°C.

- Sample Preparation:

- Plasma/Urine Extraction: Thaw samples on ice. For plasma, precipitate proteins by adding cold acetonitrile (e.g., 1:3 v/v sample:ACN), vortex, and centrifuge. Transfer the supernatant.

- Enzymatic Deconjugation: To measure total (free + conjugated) metabolites, incubate an aliquot of the extract or urine with a mixture of β-glucuronidase and sulfatase (e.g., from Helix pomatia) in acetate buffer (pH 5.0) at 37°C for several hours.

- Analysis by LC-MS/MS:

- Chromatography: Use a reverse-phase C18 column with a water-acetonitrile gradient, both acidified with 0.1% formic acid.

- Mass Spectrometry: Operate the mass spectrometer in negative electrospray ionization (ESI-) mode for most phenolic compounds. Use tandem MS (MS/MS) for structural confirmation and a scheduled MRM for high-sensitivity quantification of a predefined list of metabolites [21].

- Quantification: Quantify metabolites using stable isotope-labeled internal standards (e.g., ¹³C- or ²H-labeled analogs of target metabolites) where available, or external calibration curves.

Visualization of Pathways and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core biotransformation pathway and a standard experimental workflow.

Polyphenol Biotransformation Pathway

Diagram 1: Core pathway of microbial biotransformation of dietary polyphenols, involving deconjugation, ring fission, and bioactivation steps.

Experimental Analysis Workflow

Diagram 2: Standard workflow for the analysis of polyphenol metabolites in biological samples.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Polyphenol Biotransformation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fecal Inoculum | Provides a complex community of colonic microbes for in vitro fermentation models. | Fresh or frozen fecal samples from human donors; requires ethical approval. Pooled samples standardize community variability [21]. |

| Anaerobic Chamber/Workstation | Creates and maintains an oxygen-free environment for the cultivation of obligate anaerobic gut bacteria. | Essential for preparing culture media and setting up in vitro fermentations to mimic colonic conditions. |

| Polyphenol Substrates | The test compounds for biotransformation studies. Available as purified standards or extracts. | Purified compounds (e.g., Resveratrol, Epicatechin, Ellagic Acid); Plant/food extracts (e.g., Green Tea Extract, Pomegranate Extract) [16]. |

| Enzymes for Deconjugation | Used in vitro to hydrolyze conjugated metabolites in biofluids, revealing total metabolite levels. | β-Glucuronidase/Sulfatase (e.g., from Helix pomatia); used in sample preparation prior to LC-MS analysis [21]. |

| LC-MS/MS System with UPLC/HPLC | The core analytical platform for separating, identifying, and quantifying polyphenol metabolites. | Liquid Chromatography (UPLC/HPLC) for high-resolution separation. Tandem Mass Spectrometry (MS/MS) for sensitive and selective detection and quantification in MRM mode [21]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Added to samples before processing to correct for analyte loss during extraction and matrix effects in MS. | ¹³C- or ²H-labeled versions of target metabolites (e.g., ¹³C₆-Quercetin). Crucial for accurate absolute quantification [21]. |

| 16S rRNA Sequencing Kits | To analyze changes in the composition of the gut microbiota in response to polyphenol exposure. | Kits for DNA extraction, PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene, and library preparation for next-generation sequencing (e.g., Illumina MiSeq) [22]. |

Bile acids are classic examples of bioactive food compounds whose structure and function are extensively modified by the gut microbiota. The transformation of host-derived primary bile acids into secondary bile acids through the coordinated microbial processes of deconjugation and 7α-dehydroxylation represents a crucial gut-liver signaling axis. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of these enzymatic pathways, detailing the biochemical mechanisms, responsible microbial taxa, and experimental approaches for their investigation. Within the broader context of gut microbiota metabolism of bioactive food compounds, understanding these transformations is paramount, as the resulting secondary bile acids function as potent signaling molecules that regulate host metabolic pathways, inflammatory responses, and energy homeostasis. Disruptions in these microbial transformations have been implicated in numerous disease states, making this pathway a significant target for therapeutic intervention in metabolic, hepatic, and gastrointestinal disorders.

Bile acids (BAs) are hepatically synthesized cholesterol derivatives that function not only as dietary surfactant molecules but also as critical endocrine hormones regulating macronutrient metabolism and systemic inflammatory balance [23]. The human gut microbiome, an immensely complex ecosystem containing between 10^13 and 10^14 bacterial cells and up to 1,000 different bacterial species, performs extensive structural modifications to these primary bile acids [24]. The resulting secondary bile acids display altered receptor affinity and signaling capacity, profoundly influencing host physiology.

The biotransformation of primary bile acids to secondary bile acids occurs via a multi-step pathway initiated by deconjugation followed by 7α-dehydroxylation [24]. This review focuses specifically on these fundamental transformations, which greatly enhance the structural diversity and functional range of bile acids in the enterhepatic circulation. The resulting metabolites act as key regulators in the gut-liver axis, influencing pathways relevant to metabolic disease, inflammation, and drug development.

Biochemical Pathways of Microbial Bile Acid Modification

Deconjugation: The Gateway Reaction

Deconjugation is the initial and most widespread microbial modification of bile acids, serving as a prerequisite for most subsequent bacterial transformations [24] [25]. This process involves the hydrolysis of the amide bond linking the bile acid steroid core to the amino acid side chain (typically taurine or glycine in humans).

- Enzyme: Bile salt hydrolase (BSH; EC 3.5.1.24)

- Reaction: Catalyzes the hydrolysis of the C24 N-acyl bond, converting conjugated bile acids (e.g., Taurocholic acid, Glycocholic acid) to free bile acids (e.g., Cholic acid) and free amino acids

- Prevalence: A widespread activity among major gut bacterial phyla; over a quarter of identified bacterial strains in the human gastrointestinal tract demonstrate BSH activity [24]

- Bacterial Sources: Identified in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative species, including Bacteroides, Clostridium, Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Listeria [24]

The biological rationale for microbial deconjugation may involve bile acid detoxification, nutrient acquisition (taurine/glycine), or as a form of microbial warfare by increasing concentrations of antimicrobial free bile acids [25]. Deconjugation alters the chemical properties of bile acids, reducing their solubility and increasing their passive absorption while enabling further microbial transformations.

7α-Dehydroxylation: Generation of Secondary Bile Acids

The 7α-dehydroxylation pathway represents a more specialized microbial transformation that converts primary bile acids into secondary bile acids by removing the 7α-hydroxyl group [24]. This pathway specifically converts cholic acid (CA) to deoxycholic acid (DCA) and chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) to lithocholic acid (LCA) [24] [26].

- Organisms: Primarily identified in anaerobic Firmicutes bacteria within Clostridium clusters IV, XI, and XIVa, including species such as C. scindens, C. hylemonae, and C. hiranonis [26]

- Genetics: Encoded by the bile acid-inducible (bai) operon containing multiple genes (baiB, baiCD, baiE, baiA, baiF, baiG, baiH, baiI, and additional genes including baiJ, baiK, baiL, baiN) [24]

- Mechanism: A multi-step biochemical pathway involving oxidation, dehydration, and reduction reactions that ultimately remove the 7α-hydroxyl group

The resulting secondary bile acids DCA and LCA are more hydrophobic and comprise over 90% of fecal bile acids in healthy individuals [26]. These transformations are critical for determining the overall bile acid pool composition and subsequent signaling through various host receptors.

Figure 1: Microbial Bile Acid Transformation Pathway. Primary bile acids from the host liver undergo sequential microbial modifications: first deconjugation by BSH enzymes, then 7α-dehydroxylation by the bai operon, producing secondary bile acids that signal through host receptors.

Experimental Models and Methodologies

In Vitro Transcriptional Response Assays

RNA-Seq analysis of bile acid 7α-dehydroxylating bacteria (C. hylemonae and C. hiranonis) in the presence and absence of bile acids provides insights into gene regulation of the bai operon [26].

Protocol:

- Culture Conditions: Grow bacterial strains in brain heart infusion broth (BHI) under anaerobic conditions

- Bile Acid Exposure: Supplement medium with cholic acid (CA) or deoxycholic acid (DCA) at physiologically relevant concentrations

- RNA Extraction: Harvest cells during mid-logarithmic growth phase, extract total RNA using appropriate kits

- RNA-Seq: Prepare libraries and sequence using appropriate platform (Illumina)

- Data Analysis: Map reads to reference genomes, identify differentially expressed genes with appropriate thresholds (e.g., >0.58 log₂FC; FDR < 0.05)

Key Findings: Growth with CA results in significant differential expression of 197 genes in C. hiranonis and 118 genes in C. hylemonae, with strong upregulation of the bai operon in the presence of CA but not DCA [26].

Gnotobiotic Mouse Models

Defined bacterial communities in germ-free mice enable the study of bile acid metabolism in a controlled system [26].

Protocol:

- Bacterial Consortium: Assemble defined community (e.g., B4PC2 consortium) including:

- BSH-expressing strains: Bacteroides uniformis, B. vulgatus, Parabacteroides distasonis

- Taurine-respiring bacteria: Bilophila wadsworthia

- 7α-dehydroxylating bacteria: C. hylemonae, C. hiranonis

- Butyrate and iso-bile acid-forming bacteria: Blautia producta

- Colonization: Inoculate germ-free mice with the defined community

- Sample Collection: After established colonization, collect cecum content, serum, and liver tissue

- Analysis:

- 16S rDNA sequencing to determine community structure

- Metatranscriptomics to assess gene expression

- Bile acid metabolomics via LC-MS/MS to quantify bile acid profiles

Key Findings: The synthetic community achieves functional bile salt deconjugation, oxidation/isomerization, and 7α-dehydroxylation, with the Bacteroidetes constituting the majority (84.71%) of cecal reads, while the clostridial 7α-dehydroxylators represent <0.75% of the community yet still produce significant secondary bile acids [26].

Dietary Fiber Intervention Studies

Different fiber types distinctly modulate bile acid metabolism and gut microbiota composition, influencing deconjugation and 7α-dehydroxylation activities [27].

Protocol:

- Dietary Intervention: Feed mice control or 10% (w/w) fiber diets containing various fiber types (cellulose, chitin, resistant starch, pectin, inulin, β-glucan, psyllium, dextrin, or raffinose) for 14 days

- Sample Collection: Collect body weight measurements, cecum weight, fecal samples, liver tissue, intestinal mucosa

- Analysis:

- 16S rRNA sequencing of fecal microbiota

- Bile acid quantification in liver, intestinal mucosa, and feces via LC-MS

- Taurine and conjugate measurements

Key Findings: Fiber types differentially impact bacterial diversity, Akkermansia muciniphila abundance, and bile acid deconjugation efficiency. Inulin and β-glucan result in the highest taurine conjugate levels and reduced intestinal taurine-conjugated BA concentrations, suggesting enhanced BSH activity [27].

Quantitative Data on Bile Acid Transformations

Table 1: Impact of Dietary Fibers on Bile Acid Metabolism and Gut Microbiota [27]

| Fiber Type | Cecum Weight | Microbiota Diversity | Akkermansia Abundance | BA Deconjugation | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose | Trend decrease | Decreased | Increased | Moderate | Forms distinct microbiome cluster with chitin |

| Chitin | Trend decrease | Decreased | Increased | Moderate | Forms distinct microbiome cluster with cellulose |

| Resistant Starch | Trend decrease | Minimal change | No significant change | Minimal | Least impact on BA concentrations |

| Pectin | Increased | Decreased | Increased | High | Similar microbiota profile to psyllium |

| Inulin | Trend increase | Decreased | Increased | High | Highest taurine conjugate levels |

| β-Glucan | No significant change | Decreased | Increased | High | Reduced intestinal taurine-conjugated BAs |

| Psyllium | Increased | Decreased | Increased | High | Strongest impact on BA-related gene expression |

| Dextrin | Decreased | Decreased | Increased | Moderate | Increased β-muricholic acid in feces |

| Raffinose | No significant change | Decreased | Increased | High | Forms cluster with inulin and β-glucan |

Table 2: Bacterial Genera with Bile Acid Transformation Capabilities [24] [25] [26]

| Bacterial Group | Deconjugation (BSH) | 7α-Dehydroxylation | Other Transformations | Relative Abundance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteroides spp. | Yes (strong) | No | Oxidation, epimerization | High (can exceed 80% in models) |

| Clostridium clusters IV, XI, XIVa | Variable | Yes (specialized) | Various | Low (<1% but functionally critical) |

| Lactobacillus spp. | Yes | No | Limited | Variable |

| Bifidobacterium spp. | Yes | No | Limited | Variable |

| Listeria spp. | Yes | No | Unknown | Low |

| Blautia producta | Unknown | No | 7β-HSDH, 3α/3β-HSDH | Variable |

| Bilophila wadsworthia | No | No | Taurine respiration | Can reach 15% in models |

Table 3: Bile Acid Receptor Affinities and Signaling Effects [24] [23] [25]

| Bile Acid | FXR Agonism | TGR5 Agonism | Key Physiological Effects | Relative Potency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholic Acid (CA) | Weak | Weak | Promotes FGF15/19 secretion | Low |

| Chenodeoxycholic Acid (CDCA) | Strong | Moderate | Regulates BA synthesis, glucose metabolism | High (FXR) |

| Deoxycholic Acid (DCA) | Moderate | Strong | Glucose regulation, energy expenditure | Moderate (FXR), High (TGR5) |

| Lithocholic Acid (LCA) | Weak | Strong | Most potent natural TGR5 agonist | Low (FXR), High (TGR5) |

| Ursodeoxycholic Acid (UDCA) | Weak | Weak | Hepatoprotective, cholestasis treatment | Low |

| Tauro-β-muricholic Acid (TβMCA) | Antagonist | Weak | Blocks FXR signaling in intestine | N/A |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Studying Microbial Bile Acid Metabolism

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gnotobiotic Mice | Provides sterile host for defined microbial communities | Studying specific bacterial functions in vivo | Requires specialized facilities |

| Bile Acid Standards | Quantification and identification via LC-MS/MS | Bile acid metabolomics | Should include primary, secondary, conjugated forms |

| Anaerobic Chamber | Maintains oxygen-free environment for culturing | Growing strict anaerobic bile acid transformers | Essential for Clostridium species |

| bai Gene Primers | Detection and quantification of 7α-dehydroxylation genes | qPCR for bai operon expression | Target multiple genes in operon |

| BSH Activity Assay | Measures bile salt hydrolase activity | Testing bacterial deconjugation capability | Uses conjugated bile acids + detection of freed amino acids |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | Preserves microbial RNA for transcriptomics | RNA-Seq of bacterial responses to bile acids | Critical for accurate gene expression |

| Defined Bacterial Media | Controlled growth conditions | In vitro bile acid exposure experiments | Can supplement with specific bile acids |

| Germ-Free Verification Kits | Confirms sterility of animal models | Quality control for gnotobiotic studies | Includes culture and molecular methods |

Signaling Pathways and Physiological Implications

The microbial transformation of bile acids has profound implications for host physiology due to the altered signaling capacity of the resulting bile acid species. Secondary bile acids generated through 7α-dehydroxylation function as key regulators of metabolic pathways through their action on specific receptors.

Figure 2: Bile Acid Signaling Pathways Regulated by Microbial Transformations. Secondary bile acids produced by gut microbes signal through FXR and TGR5 receptors, regulating bile acid synthesis and metabolic homeostasis.

Receptor-Mediated Signaling Mechanisms

Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR): A nuclear receptor highly expressed in liver and intestine that regulates bile acid synthesis, lipid metabolism, and glucose homeostasis [24] [23]. Secondary bile acids like DCA function as moderate FXR agonists, while LCA is a weaker agonist. FXR activation induces enteric FGF15/19, which suppresses hepatic CYP7A1, the rate-limiting enzyme in bile acid synthesis.

TGR5 (GPBAR1): A G protein-coupled bile acid receptor expressed in various tissues, including brown adipose tissue and immune cells [24]. Secondary bile acids DCA and LCA are the most potent natural TGR5 agonists. TGR5 activation stimulates energy expenditure, improves glucose tolerance, and exerts anti-inflammatory effects.

The balance between these signaling pathways is crucial for metabolic health, and disruptions in microbial bile acid transformations have been linked to metabolic diseases including type 2 diabetes, obesity, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and cardiovascular conditions [24] [23].

The microbial enzymes responsible for bile acid deconjugation and 7α-dehydroxylation represent a critical interface between diet, gut microbiota, and host physiology. These transformations significantly expand the structural and functional diversity of bile acids, creating a complex signaling network that regulates metabolic homeostasis. The experimental approaches outlined here—including gnotobiotic models, transcriptional analyses, and dietary interventions—provide powerful tools for investigating these processes.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the full diversity of microbial enzymes involved in bile acid metabolism, developing specific modulators of these pathways, and understanding how individual variations in gut microbiota composition influence therapeutic responses. As part of the broader context of gut microbiota metabolism of bioactive food compounds, these microbial transformations represent promising targets for novel therapeutic strategies in metabolic, hepatic, and gastrointestinal disorders. The integration of quantitative metabolomic approaches with microbial community analysis will further advance our understanding of how diet, microbiota, and host health are interconnected through bile acid metabolism.

The gut microbiota has emerged as a pivotal metabolic organ, significantly expanding the host's biochemical capacity. A particularly significant aspect of this symbiotic relationship is the microbial catabolism of aromatic amino acids (AAAs)—tryptophan, phenylalanine, and tyrosine—into a diverse array of bioactive metabolites [28]. These compounds, including indole derivatives, tryptamine, and various neuroactive molecules, serve as essential communicators along the gut-brain axis and beyond, influencing host physiology from intestinal barrier function to cerebral activity [29] [30] [31]. The enzymatic pathways responsible for generating these metabolites are distributed across specific gut bacterial taxa, creating a complex metabolic network that integrates dietary inputs with host health outcomes. This technical guide synthesizes current understanding of AAA catabolism by gut microbiota, with emphasis on pathway mapping, quantitative metabolite profiling, experimental methodologies, and computational tools essential for advancing research in this rapidly evolving field. The implications extend to therapeutic development for conditions including obesity, autism spectrum disorder, and neuropsychiatric diseases, where microbial metabolite signatures are increasingly implicated [30] [31].

Core Metabolic Pathways

Tryptophan Catabolism

Tryptophan serves as a precursor for multiple host and microbial pathways, yielding metabolites with significant neuroactive and immunomodulatory properties. The gut microbiota processes tryptophan through several major routes, each generating distinct classes of metabolites.

Indole and Indole Derivative Pathway: Tryptophan is converted to indole by the enzyme tryptophanase (TnaA), present in numerous Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria including Escherichia coli, Clostridium spp., and Bacteroides spp. [29]. Indole subsequently serves as a precursor for various derivatives:

- Indole-3-aldehyde (IAld)

- Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) via the action of tryptophan monooxygenase in bacteria including Clostridium, Bacteroides, and Bifidobacterium [29]

- Indole-3-propionic acid (IPA) through conversion of indole-3-lactic acid (ILA) by bacteria including Clostridium and Peptostreptococcus possessing the phenyllactate dehydratase gene cluster (fldAIBC) [29]

Tryptamine Pathway: Tryptamine is generated via decarboxylation of tryptophan by tryptophan decarboxylases (TrpDs) present in approximately 10% of human gut bacteria, including species of Clostridium, Ruminococcus, Blautia, and Lactobacillus [29]. Germ-free studies confirm the essential microbial role in tryptamine production, with these mice exhibiting reduced gut tryptamine levels [29].

Kynurenine Pathway: While predominantly a host-mediated pathway (with >90% of tryptophan oxidized via kynurenine in the liver), gut microbiota can influence kynurenine pathway activity [29]. Key neuroactive metabolites include:

- Kynurenic acid (KYNA) - neuroprotective NMDA receptor antagonist

- Quinolinic acid (QUIN) - neurotoxic NMDA receptor agonist The balance between these metabolites (KYNA:QUIN ratio) is crucial in neurological and psychiatric conditions [29].

Serotonin Pathway: Although primarily synthesized by host enterochromaffin cells, certain gut bacteria including Streptococcus, Enterococcus, and Escherichia can produce serotonin, potentially influencing peripheral serotonin pools [32].

Table 1: Key Bacterial Genera and Their Tryptophan Metabolite Pathways

| Bacterial Genus | Tryptophan Metabolites | Key Enzymes |

|---|---|---|

| Clostridium | Indole, IAA, IPA, tryptamine | Tryptophanase, tryptophan monooxygenase, phenyllactate dehydratase, TrpD |

| Bacteroides | Indole, IAA | Tryptophanase, tryptophan monooxygenase |

| Lactobacillus | ILA, tryptamine | Aromatic amino acid aminotransferase, indolelactic acid dehydrogenase, TrpD |

| Bifidobacterium | IAA, ILA | Tryptophan monooxygenase, aromatic amino acid aminotransferase |

| Ruminococcus | Tryptamine | TrpD |

| Streptococcus | Serotonin | Undefined enzymatic pathway |

Phenylalanine and Tyrosine Catabolism

Phenylalanine and tyrosine undergo bacterial transamination via aromatic amino acid aminotransferase, yielding multiple metabolites with systemic effects:

- 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (4HPAA) - identified as a top serum metabolite negatively correlated with whole-body fat percentage in human studies [30]

- 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvic acid - direct precursor of 4HPAA, positively correlated with body fat accumulation [30]

- 4-hydroxyphenylethanol (tyrosol)

- 4-methylphenol (p-cresol)

The Clostridium sporogenes pathway generates twelve compounds from all three aromatic amino acids, nine of which accumulate in host serum and affect intestinal permeability and systemic immunity [28].

Pathway Visualization

Quantitative Metabolite Profiling

Understanding the physiological concentrations and correlations of AAA metabolites provides critical context for their potential biological significance.

Table 2: Circulating Metabolite Concentrations and Physiological Correlations

| Metabolite | Reported Concentration | Correlation with Health Parameters | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (4HPAA) | Sub-millimolar in feces [30] | Negative correlation with whole-body fat percentage, total cholesterol, LDL-C [30] | Anti-obesity effects; regulates intestinal immunity and lipid uptake |

| Kynurenate (KA) | Lower in ASD vs neurotypical children [31] | Associated with altered insular and cingulate cortical activity; correlates with ASD severity [31] | Neuroprotective NMDA antagonist; potential biomarker for ASD |

| Indole-3-propionic acid (IPA) | Reduced in conventional mice vs germ-free [29] | Potent neuroprotective properties against Alzheimer β-amyloid [28] | Blood-brain barrier permeable antioxidant |

| Tryptamine | Reduced in germ-free mice [29] | Influences serotonin response; modulates GI motility [29] | Monoamine with structural similarity to serotonin |

| Serotonin | >90% located in GI tract [29] | Central roles in emotional control, food intake, sleep [29] | Key neurotransmitter; peripheral and central pools distinct |

Table 3: Anti-Obesity Effects of Hydroxyphenyl Metabolites in Mouse Models

| Metabolite | Dosage in Drinking Water | Body Weight Reduction (HFD-fed mice) | Fat Percentage Reduction | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4HPAA | 10 mM for 8 weeks | ~45% less weight gain vs control [30] | ~23.6% vs ~36.1% in control [30] | Alleviated adipocyte hypertrophy and hepatic steatosis |

| 3HPP | 1.5 mg/mL for 8 weeks | Significant reduction [30] | Significant reduction [30] | Similar metabolomic pattern to 4HPAA |

| 4HPP | 1.5 mg/mL for 8 weeks | Significant reduction [30] | Significant reduction [30] | Structurally related analogue of 4HPAA |

| Tyrosol | 1.5 mg/mL for 8 weeks | No significant effect [30] | No significant effect [30] | Ineffective in obesity protection |

Experimental Protocols

Metabolite Quantification in Serum and Feces

Sample Preparation:

- Collect serum samples following standardized venipuncture procedures and maintain at -80°C until analysis.

- For fecal samples, homogenize in methanol (1:5 w/v) and centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- Transfer supernatant for liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis.

LC-MS/MS Parameters:

- Chromatography: Reverse-phase C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.8 μm)

- Mobile Phase: A) 0.1% formic acid in water; B) 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile

- Gradient: 5-95% B over 12 minutes, flow rate 0.3 mL/min

- Mass Detection: Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) with electrospray ionization in positive and negative modes

- Quantification: Stable isotope-labeled internal standards for each metabolite class [30]

Gnotobiotic Mouse Models

Bacterial Manipulation:

- Generate germ-free mice in flexible film isolators.

- Colonize with defined bacterial communities or specific genetically modified strains (e.g., Clostridium sporogenes with pathway knockouts) [28].

- Verify colonization status through 16S rRNA sequencing and metabolite profiling.

Metabolite Administration:

- Administer test metabolites (e.g., 4HPAA, 3HPP, 4HPP) via drinking water at concentrations of 1.5-10 mg/mL for chronic studies (8-12 weeks) [30].

- Monitor water consumption daily and body weight weekly.

- Assess body composition using EchoMRI or similar technology.

- Collect tissues for histological analysis (H&E staining for adipocyte size, Oil Red O for hepatic lipids).

Immune Cell Profiling

Cell Isolation and Analysis:

- Isolate lamina propria lymphocytes from intestinal tissues using collagenase digestion and density gradient centrifugation.

- For knockout models, utilize Rag2⁻/⁻ (lacking T and B cells) and Rag2⁻/⁻Il2rg⁻/⁻ (lacking T, B, and ILCs) mice [30].

- Analyze immune populations by flow cytometry using antibodies against CD3 (T cells), B220 (B cells), and lineage markers for innate lymphoid cells.

- Measure cytokine production (e.g., IL-22, IL-17) after ex vivo stimulation.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Category | Specific Reagents/Resources | Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Strains | Clostridium sporogenes (wild-type and engineered) [28] | Gnotobiotic mouse models | Genetic manipulation of AAA pathways |

| Cell Lines | Porcine intestinal epithelial cells (IPEC-J2) [33] | In vitro barrier function studies | Model for host-microbe interactions |

| Antibodies | Anti-CD3, Anti-B220, Anti-lineage markers [30] | Immune cell profiling by flow cytometry | Identification of lymphocyte populations |

| Chemical Inhibitors | NF-κB and MAPK pathway inhibitors [33] | Signal transduction studies | Dissection of inflammatory pathways |

| Analytical Standards | Stable isotope-labeled tryptophan, 4HPAA, kynurenine | LC-MS/MS quantification | Internal standards for precise metabolomics |

| Animal Models | Rag2⁻/⁻, Il2rg⁻/⁻, and Rag2⁻/⁻Il2rg⁻/⁻ mice [30] | Immune mechanism studies | Dissection of immune cell requirements |

Computational Analysis and Visualization

Bioinformatics Workflow

The analysis of gut microbiome data for AAA metabolism potential involves a multi-step computational pipeline:

In Silico Pathway Analysis

Computational analysis of bacterial genomes reveals enrichment of tryptophan metabolism pathways in five gut-associated phyla: Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, and Fusobacteria [32]. Specific genera with heightened tryptophan-metabolizing potential include Clostridium, Burkholderia, Streptomyces, Pseudomonas, and Bacillus [32]. This genomic potential can be analyzed through:

- Pathway Reconstruction: Map KEGG and MetaCyc pathways to metagenomic data

- Gut-Brain Module Classification: Cluster biochemical pathways into neuroactive compound production/degradation processes (56 modules identified to date) [34]

- Cross-Cohort Validation: Apply state-of-the-art bioinformatics tools to population cohorts to strengthen links between microbial disturbances and clinical outcomes [34]

The microbial catabolism of aromatic amino acids represents a crucial interface between diet, gut microbiota, and host physiology. The metabolites generated—including indoles, tryptamines, and phenolic compounds—exert profound effects on systemic health, from regulating obesity through intestinal immunity to modulating brain function and behavior. Advanced gnotobiotic models, precise metabolomic profiling, and sophisticated computational tools are enabling unprecedented dissection of these complex host-microbe metabolic interactions. As research progresses, the engineering of specific bacterial pathways to modulate host metabolite pools presents a promising therapeutic avenue for metabolic, neurological, and psychiatric conditions. The coming years will likely see the translation of these insights into targeted interventions that harness microbial metabolic potential for precision medicine applications.

The human gastrointestinal tract hosts a complex ecosystem of microorganisms, the gut microbiota, which performs extensive metabolic functions beyond the host's own enzymatic capabilities [35] [36]. While microbial fermentation of dietary carbohydrates has been extensively studied, the proteolytic fermentation of dietary proteins represents a significant pathway for generating bioactive metabolites with profound effects on host health and disease [35] [37]. This process becomes particularly important with modern dietary patterns characterized by high protein intake, which may exceed daily recommendations by 2-5 times in certain weight loss diets [35]. As dietary protein escapes host enzymatic digestion in the small intestine, it becomes available for microbial metabolism in the colon, where specialized bacteria transform amino acids into a diverse array of bioactive compounds [35] [38].

Among the most significant products of proteolytic fermentation are bioactive amines and phenols, which include compounds such as p-Cresol, phenol, indole, and various amines including histamine, tyramine, and polyamines [35] [38]. These metabolites exhibit dualistic biological roles—while some demonstrate detrimental effects on gut barrier function, immune response, and chronic disease risk, others may confer protective benefits [35]. Understanding the production, regulation, and biological activities of these compounds is essential for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to modulate gut microbiota for therapeutic purposes. This review comprehensively examines the pathways of amine and phenol production during protein fermentation, their health implications, and methodologies for their investigation in light of current scientific evidence.

Microbial Pathways of Protein Fermentation

Proteolytic Cascade and Amino Acid Catabolism

The transformation of dietary protein into bioactive amines and phenols follows a sequential metabolic cascade initiated by microbial proteases and peptidases. Undigested dietary proteins are first hydrolyzed by extracellular bacterial proteases into peptides and free amino acids, which are subsequently transported into bacterial cells for further metabolism [35]. Culture-based experiments indicate that gut bacteria preferentially assimilate and ferment peptides over single amino acids due to greater energetic efficiency [35]. Once internalized, amino acids undergo catabolic transformations through highly specific enzymes performing deamination, decarboxylation, and elimination reactions [35].

The initial deamination step liberates ammonia and keto-acids from amino acids, with the resulting carbon skeletons undergoing further transformation through decarboxylation to generate various microbial metabolites including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), branched-chain fatty acids (BCFAs), and other bioactive compounds [35]. The Stickland reaction represents a particularly important paired amino acid catabolism pathway, wherein one amino acid serves as an electron donor (commonly glycine, proline, ornithine, arginine, and tryptophan) while another serves as an electron acceptor (typically alanine, leucine, isoleucine, valine, and histidine) [35] [36]. This coordinated metabolism allows for more efficient energy extraction from amino acids under anaerobic conditions prevalent in the colon.

Table 1: Major Bacterial Pathways for Amino Acid Catabolism in the Gut

| Metabolic Pathway | Key Enzymes | Primary Substrates | Major Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deamination | Amino acid dehydrogenases, Transaminases | Most amino acids | Keto-acids, Ammonia |

| Decarboxylation | Amino acid decarboxylases | Aromatic amino acids, Lysine, Ornithine | Biogenic amines, CO₂ |

| Stickland Reaction | D-amino acid dehydrogenases | Paired amino acids (oxidized & reduced) | SCFAs, BCFAs, Ammonia |

| Ehrlich Pathway | Transaminases, Decarboxylases | Branched-chain amino acids | Branched-chain alcohols, aldehydes |

| β-Elimination | C-S lyases | Sulfur-containing amino acids | H₂S, Thiols |

Production of Bioactive Phenols

Phenolic compounds primarily derive from microbial transformation of aromatic amino acids, particularly tyrosine, tryptophan, and phenylalanine [35]. These aromatic amino acids undergo a series of deamination, decarboxylation, and reduction reactions to form various phenols with biological activity. The production of p-Cresol represents a well-characterized pathway beginning with tyrosine, which undergoes transamination to 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate, followed by decarboxylation to 4-hydroxyphenylacetate, and finally reduction to p-Cresol [35]. Similarly, phenylalanine metabolism yields phenylpropionic acid and phenol through analogous biochemical transformations.

Tryptophan metabolism occurs through multiple pathways yielding diverse metabolites with varying biological activities. The indole pathway involves deamination and decarboxylation reactions producing indole and its derivatives, while alternative pathways generate tryptamine, indole propionic acid, and indole acrylic acid [35]. Notably, certain tryptophan metabolites such as indole-3-propionate demonstrate protective effects on gut barrier function, while others like indoxyl sulfate (derived from indole) exhibit uremic toxicity and pro-inflammatory properties [35]. This duality highlights the complex relationship between proteolytic metabolites and host health.

Generation of Bioactive Amines

Bioactive amines originate primarily through decarboxylation of specific amino acids catalyzed by microbial decarboxylases [35] [38]. These enzymes utilize pyridoxal phosphate as a cofactor to remove carboxyl groups from amino acids, yielding corresponding amines and carbon dioxide. Significant amine-producing bacterial species belong to genera including Bifidobacterium, Clostridium, Lactobacillus, Escherichia, and Klebsiella [35]. The polyamines putrescine, spermidine, and spermine represent particularly important amine classes derived from arginine, ornithine, and methionine through multi-step biochemical pathways involving decarboxylation and aminopropylation reactions [35].

Bacteria utilize polyamines for various physiological functions including RNA synthesis, structural components of cell membranes and peptidoglycan, and protection against oxidative stress and acidic environments [35] [38]. This microbial production of amines during physiological stress can consequently influence bacterial pathogenicity and host susceptibility to infection. Additionally, several biogenic amines including histamine (from histidine), tyramine (from tyrosine), and tryptamine (from tryptophan) function as important signaling molecules with potential to influence host physiological processes including immune response, neurotransmission, and gastrointestinal motility [35].

Table 2: Major Bioactive Amines Derived from Protein Fermentation

| Amine Compound | Precursor Amino Acid | Producing Bacteria | Potential Biological Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histamine | Histidine | Lactobacillus, Enterococcus, Morganella | Immune modulation, Inflammation, Neurotransmission |

| Tyramine | Tyrosine | Enterococcus, Lactobacillus, Carnobacterium | Vasoconstriction, Hypertension, Neurotransmission |

| Tryptamine | Tryptophan | Ruminococcus, Clostridium | Gastrointestinal motility, Serotonergic effects |

| Putrescine | Ornithine, Arginine | Bifidobacterium, Enterobacteriaceae | Cell proliferation, Gut barrier function |

| Spermidine/Spermine | Putrescine, Methionine | Diverse gut microbiota | Anti-aging, Anti-inflammatory, Autophagy induction |

| Cadaverine | Lysine | Bacteroides, Fusobacterium | Cell differentiation, Odor compound |

Figure 1: Metabolic pathway of dietary protein to bioactive phenols and amines through microbial fermentation. Aromatic amino acids yield phenolic compounds, while decarboxylation reactions produce various bioactive amines.

Factors Influencing Production of Bioactive Metabolites

Dietary and Host Factors

Multiple dietary and host factors significantly influence the production of bioactive amines and phenols from protein fermentation. The quantity and source of dietary protein directly impact microbial metabolic activity, with high-protein diets (particularly from animal sources) consistently associated with increased production of proteolytic metabolites including ammonia, p-Cresol, and sulfur-containing compounds [35] [38]. The protein digestibility and presence of inhibitors also modulate the amount of substrate reaching colonic bacteria, with poorly digestible or modified proteins increasing proteolytic fermentation [38].