The Overestimation Problem: Evaluating Low-Cost Wearable Accuracy in Energy Expenditure Tracking for Clinical and Research Applications

This article critically examines the significant tendency of low-cost wearable devices to overestimate energy expenditure, particularly during low-to-moderate intensity activities.

The Overestimation Problem: Evaluating Low-Cost Wearable Accuracy in Energy Expenditure Tracking for Clinical and Research Applications

Abstract

This article critically examines the significant tendency of low-cost wearable devices to overestimate energy expenditure, particularly during low-to-moderate intensity activities. Targeted at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes recent validation studies, identifies the core technological and algorithmic limitations driving inaccuracies, and explores the implications for clinical trials and metabolic research. The review further discusses emerging methodological approaches for data correction, provides a framework for device validation, and outlines future directions for improving the reliability of wearable-derived energy metrics in biomedical applications.

The Evidence Base: Documenting Systemic Overestimation in Consumer Wearables

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is there such a high error rate in energy expenditure estimation from consumer wearables?

The high error rate stems from multiple factors. The devices often rely on algorithms, like the Mifflin-St. Jeor equation, to estimate Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) based on user-provided data (age, sex, weight, height), which is then used as a base for calculating total energy expenditure [1]. The estimation of active calories through motion sensors and heart rate is complex and can be influenced by the type of activity, with steady-state activities like walking often yielding more accurate results than irregular movements like cycling or household chores [1]. Furthermore, a major systematic review and meta-analysis of combined-sensing Fitbit devices concluded that they consistently underestimate energy expenditure, with an average bias of -2.77 kcal per minute compared to criterion measures [2]. Studies on low-cost smartwatches have also shown significant overestimation, with Mean Absolute Percentage Errors (MAPE) ranging from 15.0% to 57.4% in some devices [3].

Q2: What is the "gold standard" method for validating wearable energy expenditure data?

The gold standard method referenced in validation studies is indirect calorimetry [3] [2]. This method uses a metabolic cart, such as the CORTEX METAMAX 3B, to measure the body's gas exchange—specifically, oxygen consumption (VO₂) and carbon dioxide production (VCO₂)—on a breath-by-breath basis [3]. These values are then entered into equations, such as the Weir equation, to calculate energy expenditure with high precision [4] [3]. This setup serves as the criterion measure against which the estimates from wearable devices are compared in controlled laboratory settings.

Q3: What are common hardware and software issues that can affect data accuracy?

Common issues that researchers should account for include:

- Sensor Inaccuracies: Inconsistent or inaccurate readings from accelerometers or photoplethysmography (PPG) heart rate sensors due to hardware defects, improper placement on the wrist, or external factors like temperature and humidity [5].

- Connectivity Issues: Problems with Bluetooth pairing or syncing can lead to data loss or corruption. Ensuring devices are fully charged, within range, and have updated firmware can mitigate these issues [6] [5].

- Battery Problems: Low battery life or unexpected shutdowns can interrupt data collection. Using manufacturer-recommended chargers and procedures is essential for maintaining device function [5].

Q4: My wearable device is overestimating EE in my study cohort. How should I address this?

First, characterize the error by comparing your device's data to a gold standard like indirect calorimetry for a subset of your participants under controlled conditions [3] [2]. This will allow you to quantify the bias (e.g., mean absolute percentage error) for your specific population and device model. Based on this, you can develop a calibration or correction factor to apply to your dataset. It is also critical to clearly report the device's known error and your correction methodology in your research findings to ensure transparency.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Mitigating High Error Rates in EE Data

| Step | Action | Rationale & Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Verify Criterion Method | For validation studies, ensure proper calibration of the indirect calorimetry device using a 3L syringe and calibration gases prior to each data collection session [3]. | Calibration is fundamental for accurate measurement of VO₂ and VCO₂, which are used in the Weir equation to establish the ground truth for EE [3]. |

| 2. Control Device Setup | Place the wearable device on the wrist according to the manufacturer's instructions, ensuring a secure but comfortable fit. Assign device placement (left/right wrist) randomly to control for placement bias [3]. | Improper fit can affect the accuracy of both accelerometer and PPG heart rate sensors. Randomization helps account for any potential differences related to limb dominance. |

| 3. Standardize Protocol | Design experimental protocols that account for different activity types (e.g., steady-state vs. intermittent) and intensities, and ensure consistent conditions across all participants. | EE estimation error is not uniform; it varies significantly with the type and intensity of physical activity. A structured protocol helps identify these specific error patterns [1]. |

| 4. Quantify the Error | Calculate statistical measures of agreement between the wearable and the criterion measure. Key metrics include Mean Bias, Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), and Limits of Agreement (LOA) from Bland-Altman analysis [3] [2]. | A meta-analysis of Fitbit devices used Bland-Altman methods, finding a population LOA for EE of -12.75 to 7.41 kcal/min, highlighting the large range of individual error [2]. |

| 5. Apply Corrections | Based on the quantified bias, develop a device- and population-specific correction factor or algorithm to adjust the raw EE data from the wearable. | This step is crucial for improving the validity of data used in subsequent analysis, especially given the documented systematic underestimation or overestimation trends [2] [1]. |

Guide 2: Resolving Connectivity and Data Sync Issues

| Issue | Symptom | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Bluetooth Pairing Failure | The wearable device fails to pair with the data collection smartphone or tablet. | Check and enable all necessary app permissions (Bluetooth, Location Services). Update the device's firmware and companion app to the latest versions. Unpair and then re-pair the device [6] [5]. |

| Intermittent Data Sync | Data transfers from the wearable to the server are inconsistent, with gaps or delays. | Ensure both the wearable and the paired device have adequate battery charge (ideally >20%). Keep the devices within 30 feet and minimize physical obstructions and interference from other electronic devices [6] [5]. |

| Data Transmission Latency | A significant delay is observed between data collection on the wearable and its appearance in the research database. | Optimize the Bluetooth configuration for a lower connection interval if possible. Check for and reduce packet loss. Implement data compression techniques to reduce payload size before transmission [6]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Validation of Wearable EE Estimation During Ergometer Cycling

This protocol is adapted from a 2025 study investigating the validity of low-cost smartwatches in untrained women [3].

Objective: To assess the validity of energy expenditure estimates from wearable devices during graded cycling exercise against the criterion of indirect calorimetry.

Key Reagent Solutions:

- CORTEX METAMAX 3B (MM3B): A portable metabolic system used as the criterion measure. It collects breath-by-breath gas exchange data (VO₂ and VCO₂) [3].

- Polar H10 Heart Rate Belt: A validated chest-strap ECG heart rate monitor used to provide a secondary criterion measure for heart rate [3].

- Weir Equation: The equation used to convert gas exchange measurements (VO₂ and VCO₂) into energy expenditure (kcal/min) [3].

Methodology:

- Participant Preparation: Screen participants according to inclusion/exclusion criteria (e.g., healthy, sedentary/slightly active). Instruct them to avoid caffeine, smoking, and strenuous activity before testing.

- Device Calibration: Calibrate the MM3B device according to manufacturer specifications using a 3L calibration syringe and certified calibration gases [3].

- Device Setup: Fit the MM3B mask and Polar H10 belt on the participant. Securely fit two smartwatches (randomly assigned to wrists) according to manufacturer guidelines, ensuring proper sensor contact.

- Testing Protocol: Have the participant perform cycling on an ergometer at incremental power outputs (e.g., 30W, 40W, 50W, 60W). Maintain each stage for a sufficient duration (e.g., 4-5 minutes) to reach a steady state.

- Data Collection: Simultaneously record EE and heart rate from the MM3B (criterion), Polar H10, and all smartwatches throughout the protocol.

- Data Analysis: Calculate EE from MM3B using the Weir equation. Compare smartwatch EE estimates to the criterion using statistical measures like MAPE, bias, and Bland-Altman analysis [3].

Protocol 2: Meta-Analytical Approach for Quantifying Device Bias

This protocol is based on a 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis of combined-sensing Fitbit devices [2].

Objective: To quantitatively synthesize evidence and quantify the population-level bias and limits of agreement for energy expenditure, heart rate, and steps measured by recent wearable devices.

Methodology:

- Literature Search: Conduct a systematic search of electronic databases (e.g., PubMed, Embase) for validation studies published within a specified timeframe.

- Study Selection: Apply strict inclusion criteria: studies must compare a wearable device against a valid criterion measure (e.g., indirect calorimetry for EE, electrocardiogram for HR, direct observation for steps) [2].

- Data Extraction: Extract key statistics from included studies: mean bias (device - criterion), standard deviation of bias, and sample size for each comparison. Convert EE and steps to a per-minute rate if necessary.

- Data Synthesis: Perform a Bland-Altman meta-analysis. Pool the mean bias and standard deviation of the differences to calculate the population limits of agreement (LOA) for each metric (EE, HR, steps) [2].

- Heterogeneity Analysis: Investigate sources of heterogeneity, such as the specific device model, participant age, type of activity performed, and risk of bias in the primary studies.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Accuracy of Selected Wearables in Estimating Energy Expenditure

Data from controlled laboratory studies comparing devices to indirect calorimetry.

| Device / Brand | Study Type | Average Bias (vs. Criterion) | Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Various Fitbit Models | Meta-Analysis (2022) [2] | -2.77 kcal/min | Not Reported | Systematic underestimation of EE; LOA: -12.75 to 7.41 kcal/min. |

| XIAOMI Smart Band 8 (XMB8) | Experimental (2025) [3] | Overestimation | 30.5% - 41.0% | Significantly overestimated EE at all cycling load levels. |

| HONOR Band 7 (HNB7) | Experimental (2025) [3] | Not Significant | 15.0% - 23.0% | Demonstrated moderate accuracy with no significant over/underestimation. |

| HUAWEI Band 8 (HWB8) | Experimental (2025) [3] | Not Significant | 12.5% - 18.6% | Showed the best accuracy among the four low-cost devices tested. |

| KEEP Smart Band B4 Lite (KPB4L) | Experimental (2025) [3] | Overestimation | 49.5% - 57.4% | Showed the highest error, severely overestimating EE. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for EE Validation Studies

Key equipment and tools required for establishing a rigorous validation protocol.

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Portable Indirect Calorimetry System (e.g., CORTEX METAMAX 3B) | Serves as the criterion measure for Energy Expenditure. It directly measures oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production, which are used to calculate EE via established equations [3]. |

| Calibration Syringe & Gases | Essential for the precise calibration of the metabolic cart before each use, ensuring the accuracy of gas volume and concentration measurements [3]. |

| Ergometer (Cycle or Treadmill) | Provides a controlled and standardized environment for administering exercise protocols at precise intensities. |

| Validated Chest-Strap Heart Rate Monitor (e.g., Polar H10) | Provides a secondary criterion measure for heart rate, which is a key input for the algorithms in combined-sensing wearables [3]. |

| Statistical Analysis Software (e.g., R, Python) | Used for conducting specialized statistical analyses, such as Bland-Altman plots and calculation of Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), to quantify device agreement with the criterion [3] [2]. |

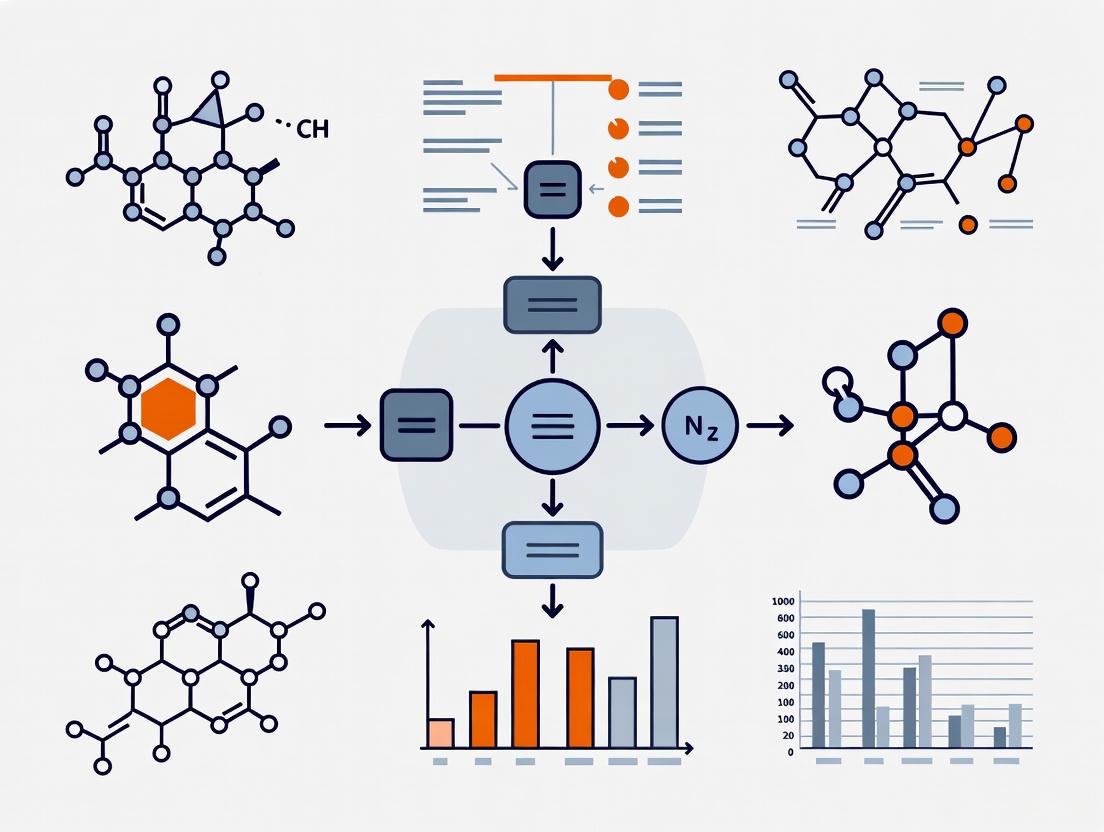

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

In the validation of wearable technologies designed to estimate calorie intake, the Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) is a widely used metric for assessing model accuracy. It measures the average absolute percentage difference between predicted values from a device and actual, ground-truth values [7]. However, within the specific context of research on wearables for low calorie intake estimation, the use of MAPE presents significant and often misunderstood challenges. Its mathematical formulation can systematically overstate the error for low actual values, potentially misrepresenting the device's true performance and biasing model evaluation [8] [7] [9]. This technical guide addresses the specific issues researchers encounter when using MAPE in this field.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inflated MAPE Values Due to Low Actual Intake

The Issue Your analysis shows an excessively high MAPE, but a visual inspection of the data suggests the wearable's estimates are reasonably close, especially for larger calorie values.

Diagnosis This is a classic symptom of MAPE's sensitivity to low actual values. The error is divided by the actual value (At), so when At is small (e.g., a small snack or a beverage), even a minor absolute difference between the forecast (Ft) and the actual value can result in an extremely large percentage error, disproportionately inflating the overall MAPE [8] [9].

Solution

- Calculate Absolute Errors: First, review the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) to understand the average error in the original units (e.g., kilocalories), which is not skewed by small denominators [7].

- Implement a Threshold: For all actual values below a physiologically meaningful threshold (e.g., < 50 kcal), consider calculating the absolute error instead of the percentage error.

- Use an Alternative Metric: For a more balanced view, adopt the Weighted Mean Absolute Percentage Error (WMAPE). WMAPE uses the sum of the absolute errors divided by the sum of the actual values, which prevents low individual values from dominating the metric [8].

Table: Impact of Low Actual Values on MAPE

| Actual Value (kcal) | Predicted Value (kcal) | Absolute Error (kcal) | Absolute Percentage Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 12 | 2 | 20.0% |

| 400 | 360 | 40 | 10.0% |

| 5 | 9 | 4 | 80.0% |

| Overall MAPE | 36.7% |

In the table above, the single, small error of 4 kcal on an actual value of 5 kcal contributes disproportionately to the overall MAPE, making the model's performance appear worse than the absolute errors suggest.

Problem 2: MAPE Favors Underestimation of Low Intake

The Issue During model training or selection, you find that a model which systematically underestimates low calorie intake achieves a slightly better (lower) MAPE than a more accurate model.

Diagnosis MAPE has a known inherent bias. For the same absolute error, the penalty is higher when over-predicting a small actual value than when under-predicting it [8] [7]. This can inadvertently guide algorithms towards models that produce low-biased forecasts.

Solution

- Audit for Bias: Systematically check the direction of errors in your model. Plot the residuals (Actual - Predicted) against the actual values to visually identify any systematic under- or over-prediction patterns.

- Use a Symmetric Metric: Consider metrics less sensitive to this bias, such as the Mean Arctangent Absolute Percentage Error (MAAPE) or the use of scaled errors like Mean Absolute Scaled Error (MASE) [8].

- Complement with MAE: Always report MAE alongside MAPE to provide a clear picture of the unbiased average error magnitude [9].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is an acceptable MAPE value for a wearable calorie intake estimator? There is no universal standard for an "acceptable" MAPE, as it is highly context-dependent [7]. However, for reference, a validation study of popular smartwatches for estimating energy expenditure during physical activity reported MAPEs ranging from 9.9% to 32.0% [10]. The key is to compare your model's MAPE against a naive baseline or existing solutions in the literature, rather than targeting an arbitrary number.

Q2: Our data includes instances of zero calorie intake (fasting). How should we handle MAPE calculation? MAPE is undefined when actual values are zero, as it leads to division by zero [8] [9]. Your options are:

- Exclude Zero Points: Remove these data points from the MAPE calculation, but document this exclusion thoroughly as it may bias your results.

- Use WMAPE: Shift to WMAPE, which aggregates errors before calculating a single percentage and avoids division by zero for individual points [8].

- Switch Metrics: Use a different metric entirely, such as Mean Absolute Error (MAE) or Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), for which zero values are not problematic [7].

Q3: Why is WMAPE a better choice for our low-calorie intake research?

WMAPE (Weighted Mean Absolute Percentage Error) is often a more robust choice because it calculates error as a single percentage across the entire dataset. Its formula, WMAPE = SUM(|A_i - F_i|) / SUM(|A_i|), prevents individual low actual values from having an outsized impact on the final result. This provides a more stable and representative measure of overall model accuracy in datasets with a wide range of values [8].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

To ensure the rigorous validation of wearable devices, the following methodological details are critical.

Reference Method for Calorie Intake Validation

A robust validation study requires a highly accurate reference method against which the wearable device is compared.

- Objective: To validate the accuracy of a wearable wristband in estimating daily energy intake (kcal) in free-living adults [11] [12].

- Design: Participants use the wearable device over two 14-day test periods. The reference method involves collaboration with a metabolic kitchen where all meals are prepared, calibrated, and served. Participants consume these meals under direct observation, allowing for precise recording of their true energy and macronutrient intake [12].

- Statistical Analysis: The agreement between the wearable device and the reference method is typically assessed using Bland-Altman analysis, which calculates the mean bias (average difference) and the limits of agreement [12].

Protocol for Activity-Based Energy Expenditure Validation

When validating energy expenditure, indirect calorimetry is the gold standard.

- Objective: To assess the validity of smartwatches in estimating energy expenditure (EE) during structured outdoor walking and running [10].

- Design: Participants concurrently wear the smartwatches and a portable gas analysis system (e.g., COSMED K5). They perform standardized exercises, such as walking 2 km at 6 km/h and running 2 km at 10 km/h, on an outdoor track [10].

- Data Collection: The portable gas analysis system provides breath-by-breath measurement of oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production, from which criterion EE is calculated. The smartwatch estimates are recorded simultaneously [10].

- Statistical Analysis: Use paired-sample t-tests to check for significant differences between the device and the criterion. Report MAPE, Limits of Agreement (LoA), and Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) [10].

Visualizing the MAPE Problem in Low-Calorie Contexts

The following diagram illustrates how the MAPE calculation reacts differently to errors at high and low actual values, leading to potential misinterpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Materials and Tools for Wearable Validation Research

| Item & Purpose | Function in Research | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Portable Metabolic System (Indirect Calorimeter) | Serves as the criterion measure (gold standard) for validating energy expenditure estimates from wearables by measuring respiratory gases [10]. | COSMED K5 system [10]. |

| Metabolic Kitchen & Calibrated Meals | Provides the ground truth for energy and macronutrient intake, enabling precise validation of dietary intake wearables against known inputs [12]. | University dining facility collaboration with precisely prepared meals [12]. |

| Consumer-Grade Wearables | The devices under test. Used to collect prediction data for energy intake, expenditure, and other physiological parameters [10] [13]. | Apple Watch Series 6, Garmin FENIX 6, Huawei Watch GT 2e, Fitbit trackers [10] [14]. |

| Statistical Analysis Software | Used to calculate performance metrics (MAPE, WMAPE, MAE), perform Bland-Altman analysis, and conduct significance testing [10] [12]. | SPSS, R, or Python with relevant statistical libraries [10]. |

| Wearable Cameras | Provides an objective, passive record of food consumption to assist in improving the accuracy of self-reported dietary recalls [15]. | Narrative Clip camera [15]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols for researchers investigating the performance of consumer-grade wearables against criterion standards, with a specific focus on the context of calorie intake estimation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our experimental data shows that a consumer-grade wearable device consistently overestimates calorie expenditure compared to laboratory standards. What are the primary factors we should investigate?

A1: The overestimation of calorie expenditure is a common challenge. Your investigation should focus on these primary factors:

- Algorithmic Limitations: Consumer devices often use proprietary, generalized algorithms that may not account for individual variations in metabolism, fitness level, or the specific type of physical activity being performed [16].

- Sensor Placement and Type: Devices using wrist-worn photoplethysmogram (PPG) sensors are highly susceptible to motion artifacts. Higher intensity movement can significantly reduce the accuracy of heart rate measurements, which is a key input for calorie estimation models [17].

- Lack of Individual Calibration: Unlike controlled laboratory equipment, consumer devices are rarely calibrated for the individual user's physiological characteristics, such as weight, height, age, and basal metabolic rate, leading to systematic errors [16].

Q2: When validating a low-cost wearable for a research study, what is the minimum participant sample size and study duration required for a robust validation?

A2: While requirements vary by study goal, a practical guide recommends that for continuous monitoring, the device should be capable of passive data collection for a minimum of 24 hours a day for seven consecutive days. This duration captures sufficient data on daily activities and behaviors to account for natural variance [18]. The sample size should be large enough to provide statistical power for subgroup analyses (e.g., by BMI, age), a consideration often missed in early-stage pilot studies that fail to replicate in larger trials [16].

Q3: What are the key regulatory considerations when using data from consumer wearables in a clinical trial context?

A3: Regulatory bodies like the FDA emphasize a "Fit-for-Purpose" framework. Key considerations include:

- Verification: Confirming the device accurately and precisely measures the physical parameter it claims to (e.g., acceleration) [19].

- Analytical Validation: Demonstrating that the derived measurement (e.g., step count, calorie expenditure) accurately assesses the clinical characteristic in your specific participant population [19].

- Clinical Validation: Providing evidence that the measurement is associated with the clinical outcome or endpoint of interest [20]. Always consult the latest FDA guidance on Digital Health Technologies (DHTs) for remote data acquisition [20].

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Tests

Protocol 1: Validating Caloric Expenditure Against a Criterion Standard

Objective: To compare the caloric expenditure output of a low-cost wearable (e.g., Xiaomi, Keep) against the criterion method of indirect calorimetry.

Materials:

- Criterion: Portable indirect calorimetry system (metabolic cart).

- Test Devices: Low-cost wearable devices (e.g., wrist-worn activity trackers).

- Treadmill or cycle ergometer.

- Standardized participant preparation guidelines (e.g., fasting state, no caffeine).

Methodology:

- Participant Setup: Equip the participant with the indirect calorimetry mask and the wearable device(s) according to manufacturer instructions.

- Protocol Execution: Conduct a graded exercise test. For example, stages of 3-5 minutes at increasing intensities (e.g., 3 km/h, 5 km/h, 7 km/h, and 9 km/h on a treadmill).

- Data Collection: Simultaneously record the caloric expenditure value from the indirect calorimetry system (criterion) and the wearable device(s) at the last 30 seconds of each stage when steady-state is achieved.

- Data Analysis: Use Bland-Altman analysis to assess the bias and limits of agreement between the wearable and the criterion measure. Calculate the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) for each device.

Protocol 2: Assessing Heart Rate Accuracy in a Free-Living Setting

Objective: To evaluate the accuracy of wearable-derived heart rate data during unstructured activities, a key input for calorie estimation models.

Materials:

- Criterion: 12-lead Holter electrocardiogram (ECG) or a validated ambulatory ECG system [17].

- Test Devices: Low-cost wearable devices.

- Activity diary for participants.

Methodology:

- Device Setup: A certified technician places the Holter ECG on the participant. The wearable device is fitted according to its manual (e.g., snug on the wrist) [17].

- Monitoring Period: Participants are instructed to go about their normal daily routine for 24 hours, including various activity types (sedentary, walking, climbing stairs) while avoiding showering or swimming [17].

- Data Synchronization: Participants log their activities and any symptoms in a diary. All devices should be synchronized to a common time server at the start and end of the monitoring period [17].

- Data Analysis: Perform time-matched analysis of heart rate data from the wearable and the Holter ECG. Calculate accuracy as the percentage of wearable HR readings within ±10% of the concurrent ECG value. Investigate how accuracy varies with the level of bodily movement using accelerometry data [17].

The table below summarizes findings from validation studies, which are critical for benchmarking expectations.

| Study Focus | Criterion Device | Test Device | Key Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Rate Accuracy in Pediatrics [17] | 24-hour Holter ECG | Corsano CardioWatch (Wristband) | Mean HR Accuracy (% within 10% of ECG) | 84.8% (SD 8.7%) |

| Heart Rate Accuracy in Pediatrics [17] | 24-hour Holter ECG | Hexoskin Smart Shirt | Mean HR Accuracy (% within 10% of ECG) | 87.4% (SD 11%) |

| Impact on Weight Loss [21] | Standard diet/exercise plan | Fit Core Armband | Average Weight Loss (over 2 years) | 7.7 lb (Device Group) vs. 13.0 lb (Control Group) |

| Heart Rate Accuracy vs. Movement [17] | Holter ECG | Corsano CardioWatch | Accuracy at Low vs. High HR | 90.9% vs. 79.0% (P<.001) |

Experimental Workflow and Logical Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for designing a validation study for consumer wearables, from defining the purpose to the final data interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This table details key materials and their functions for conducting rigorous wearable validation studies.

| Item | Function in Validation Research |

|---|---|

| Indirect Calorimetry System | Considered the criterion method for measuring caloric expenditure and energy consumption by analyzing inhaled and exhaled gases. |

| Holter Electrocardiogram (ECG) | The gold-standard ambulatory device for continuous, medical-grade heart rate and rhythm monitoring against which wearables are validated [17]. |

| Controlled Environment Ergometer | A treadmill or cycle ergometer allows for the precise control of exercise intensity during standardized laboratory validation protocols. |

| Accelerometer (Reference Grade) | Used to objectively quantify the intensity of bodily movement, allowing researchers to analyze how motion artifacts impact wearable accuracy [17]. |

| Data Synchronization Tool | A critical tool or protocol (e.g., common time server, synchronized start/stop) to ensure timestamps from all devices are aligned for precise, time-matched analysis [17]. |

| Bland-Altman Analysis Software | A statistical method and software package used to assess the agreement between two measurement techniques by plotting the difference between them against their average [17]. |

The Impact of Activity Type and Intensity on Measurement Accuracy

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Energy Expenditure (Calorie) Measurement Inaccuracies

Reported Issue: Significant discrepancies in energy expenditure (calorie) measurements during experimental data collection, particularly an observed overestimation of intake at lower calorie levels.

Investigation Procedure:

- Verify Activity Type & Intensity: Confirm the specific physical activities performed by study participants. Note that energy expenditure error margins are largest during physical activity, with Mean Absolute Percentage Errors (MAPE) reported from 29% to 80% depending on intensity, and absolute bias can range from -21.27% to 14.76% [22] [23].

- Cross-Reference with Gold Standards: Validate device outputs against criterion measures. For energy expenditure, the gold standard is indirect calorimetry (measuring oxygen and carbon dioxide in breath) [24]. One study found the most accurate device was off by 27% on average, and the least accurate by 93% [24].

- Check for Signal Artifacts: Review data for periods of transient signal loss, which is a major source of error in computing dietary and energy intake [11].

- Review Device Algorithm Specifications: Consult manufacturer documentation for the proprietary algorithm used to convert sensor data into energy expenditure. Be aware that these algorithms may make assumptions that do not fit individuals well across diverse populations [24].

Resolution Steps:

- For low-intensity activity monitoring: Apply a calibration factor or correction equation based on validation studies. One study of a nutritional intake wristband found a regression equation of Y=-0.3401X+1963, indicating a tendency to overestimate lower calorie intake and underestimate higher intake [11].

- For high-intensity or variable-intensity protocols: Use device data as a relative measure rather than an absolute value, focusing on intra-participant changes over time.

- For all studies: Clearly report the specific wearable device models, firmware versions, and the algorithms they use in your methodology, as these factors significantly impact results [22] [25].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Heart Rate Measurement Variability

Reported Issue: Inconsistent heart rate data across different activity types or participant demographics.

Investigation Procedure:

- Identify Activity Context: Determine if inaccuracies occur during rest, steady-state exercise, or activities involving cyclical arm motion (e.g., running, cycling). Heart rate accuracy is generally high at rest but can degrade during activity [26]. The mean absolute error (MAE) during activity can be 30% higher than during rest [26].

- Assess Participant Factors: While one systematic review found no statistically significant difference in heart rate accuracy across skin tones [26], other studies note that factors like skin tone and BMI can affect measurements [24].

- Inspect for Motion Artifacts: Analyze accelerometer data concurrent with PPG data. Motion artifacts from sensor displacement or cyclical wrist motions can cause false beats or signal crossover, where the device locks onto the motion frequency instead of the heart rate [26].

Resolution Steps:

- For activities with high motion artifact risk: Use a chest-strap ECG monitor as a gold standard for validation in a subset of participants [26].

- For general use: Note that most consumer wearables measure heart rate with an error rate of less than 5% and are reasonably accurate for resting and prolonged elevated heart rate [24]. They can be reliably used for heart rate measurement in non-medical settings [24].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: For which biometric measures are consumer wearable devices considered acceptably accurate for research purposes?

Consumer wearables have demonstrated good accuracy for several key metrics, though error rates vary.

- Heart Rate: Generally high accuracy. Error rates are typically below 5% [24], with a mean bias of approximately ± 3% [22]. For specific conditions like atrial fibrillation detection, sensitivity can be as high as 94.2% and specificity 95.3% [27].

- Step Count: Accuracy is generally high, with devices showing a tendency to slightly underestimate steps. Mean Absolute Percentage Errors (MAPE) range from -9% to 12% [22] [23].

- Distance: Can be reliably measured, with MAPE approximately 0.10 according to one multi-device study [28].

- Sleep Duration: Measurement is possible but often overestimates total sleep time. Overestimation is typically >10%, and errors for sleep onset latency can range from 12% to 180% compared to polysomnography [23].

FAQ 2: Which metrics have the poorest accuracy and should be interpreted with caution?

Energy Expenditure (Calories Burned) and Energy Intake are the least accurate metrics [11] [14] [24].

- Energy Expenditure: Error is significant and variable. One umbrella review found a mean bias of -3 kcal per minute (-3%), with error margins ranging from -21.27% to 14.76% [22]. Another study found the most accurate device was off by an average of 27% [24].

- Energy Intake (via automated tracking): One study on a dedicated wristband found high variability, with a mean bias of -105 kcal/day and wide 95% limits of agreement between -1400 and 1189 kcal/day. The device tended to overestimate lower calorie intake and underestimate higher intake [11].

FAQ 3: How does the type of physical activity affect the accuracy of wearable device data?

Activity type and intensity are major factors influencing accuracy [28] [26].

- Heart Rate: Accuracy is highest during rest and prolonged, steady elevated heart rate. It decreases during physical activity, with the mean absolute error being 30% higher during activity than at rest [26]. Activities causing cyclical wrist motion (e.g., running, cycling) can introduce "signal crossover" errors [26].

- Energy Expenditure: The algorithms used by wearables have varying performance across different activity states (e.g., walking, running, cycling), leading to significant variations in measurement accuracy for the same indicator [28].

FAQ 4: What are the primary sources of inaccuracy in wearable optical heart rate sensors?

The main sources of inaccuracy are [26] [25]:

- Motion Artifacts: Sensor displacement or skin deformation during movement.

- Signal Crossover: The sensor mistakenly locking onto the frequency of repetitive body motion instead of the heart pulse.

- Device-Specific Factors: Variations in sensor quality, proprietary algorithms, and device placement.

FAQ 5: What methodological challenges exist when using wearable devices in scientific research?

Key challenges include [22] [29] [23]:

- Rapid Obsolescence: The academic validation cycle is slower than the commercial release cycle of new devices and software updates. Less than 5% of released consumer wearables have been validated for the physiological signals they claim to measure [23].

- Lack of Standardization: Inconsistent validation methodologies across studies make cross-comparison of results difficult.

- Data Quality Issues: Wearables can produce noisy or incomplete data, and data loss can occur [29].

- Proprietary Algorithms: The "black box" nature of algorithms used to compute metrics like energy expenditure makes it difficult to understand or adjust for errors [24].

Table 1: Summary of Wearable Device Accuracy by Biometric Metric

| Biometric Metric | Reported Accuracy / Error | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Heart Rate | Mean bias: ± 3% [22]Error rate: < 5% for most devices [24] | Activity type & intensity [26], specific device model [26] |

| Energy Expenditure | Error range: -21.27% to 14.76% [22]Most accurate device off by 27% on average [24] | Activity intensity, individual user factors (fitness, BMI) [24], device algorithm [24] |

| Step Count | MAPE range: -9% to 12% (generally underestimates) [22] [23] | - |

| Sleep Duration | Overestimation typically >10% [23] | - |

| Energy Intake | Mean bias: -105 kcal/day95% Limits of Agreement: -1400 to 1189 kcal/day [11] | Transient signal loss, device algorithm tending to overestimate low intake/underestimate high intake [11] |

Table 2: Key "Research Reagent Solutions" for Experimental Validation

| Item | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Indirect Calorimetry Unit | Gold standard for measuring energy expenditure (calories burned) via oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production analysis [24]. |

| Electrocardiogram (ECG) | Gold standard for heart rate measurement, used as a reference to validate optical heart rate sensors in wearables [26] [24]. |

| Actigraphy System | Research-grade system for measuring sleep and wake patterns, used as a criterion for validating consumer sleep tracking [23]. |

| Polysomnography (PSG) | Comprehensive gold standard for sleep measurement, including brain waves, eye movements, and muscle activity, used in clinical sleep studies [23]. |

| Calibrated Study Meals | Precisely prepared meals with known energy and macronutrient content, used to validate automated dietary intake estimation of wearables [11]. |

Experimental Protocol Detail

Protocol 1: Validation of Energy Expenditure Estimation During Controlled Physical Activities

This protocol is designed to assess the accuracy of wearable devices in estimating energy expenditure across different activity types and intensities, a key factor in understanding overall energy balance.

- Objective: To evaluate the validity of energy expenditure estimates from wearable devices against a gold standard measure under various seminatural activity states.

- Criterion Measure: Indirect calorimetry (portable metabolic unit) measuring oxygen consumption (VO₂) and carbon dioxide production (VCO₂) for calculating energy expenditure [24].

- Experimental Workflow:

- Participant Preparation: Fit participant with the wearable device(s) under investigation and the portable metabolic unit.

- Baseline Measurement: Participant rests in a seated position for a set period (e.g., 10-15 minutes) to establish baseline energy expenditure.

- Activity Trials: Participant performs a series of activities, each for a predetermined duration (e.g., 5-10 minutes). Typical activities include:

- Treadmill walking at a slow pace

- Treadmill running at a moderate pace

- Cycling on a stationary bicycle

- Data Synchronization: Timestamps from the wearable device and the metabolic unit are synchronized post-test.

- Data Analysis: Energy expenditure values from the wearable device are compared to those from the metabolic unit at concurrent time points. Statistical analysis includes calculating Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), absolute bias, and limits of agreement [11] [28].

Experimental Workflow for Energy Expenditure Validation

Protocol 2: Investigating Heart Rate Sensor Accuracy Across Skin Tones and Activity

This protocol systematically explores potential sources of inaccuracy in optical heart rate sensors, including the effect of activity type and participant demographics.

- Objective: To determine the accuracy of wearable optical heart rate sensors across the full range of skin tones and under different activity conditions.

- Criterion Measure: Electrocardiogram (ECG) chest patch, recorded concurrently with wearable data [26].

- Experimental Workflow:

- Participant Screening & Consent: Recruit a diverse participant group equally representing all skin tones (e.g., using the Fitzpatrick scale). Obtain informed consent.

- Device Fitting: Participant is fitted with the ECG patch and multiple wearable devices on the wrist.

- Protocol Rounds: Participants complete a structured protocol multiple times to test all devices. The protocol for each round includes:

- Seated Rest: 4 minutes to establish baseline heart rate.

- Paced Deep Breathing: 1 minute to introduce mild parasympathetic activation.

- Physical Activity: 5 minutes of walking to increase heart rate.

- Seated Rest (Washout): ~2 minutes to return to near baseline.

- Typing Task: 1 minute to simulate low-intensity, non-cyclic movement.

- Data Analysis: Heart rate data from wearables is compared to the ECG gold standard. Analysis focuses on Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and directional error. Mixed effects statistical models are used to examine the impact of device, activity condition, and skin tone [26].

Heart Rate Validation Protocol Across Activities

Under the Hood: Technological Drivers of Error and Emerging Solutions

This technical support guide addresses a critical challenge in digital health research: the systematic overestimation of energy expenditure (EE) by wrist-worn wearables, particularly in contexts of low calorie intake or specific population groups. These inaccuracies primarily stem from the technological limitations of photoplethysmography (PPG) and accelerometry sensors, and the algorithms that interpret their data. The following FAQs, troubleshooting guides, and experimental protocols are designed to help researchers identify, understand, and mitigate these errors in their studies, thereby improving the validity of data collected for clinical research and drug development.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Limitations

1. What are the primary sources of inaccuracy in wearable-based EE estimation? Inaccuracies in EE estimation arise from a combination of sensor limitations and algorithmic shortcomings. The key sources include:

- Motion Artifacts: Physical movement can corrupt the PPG signal, leading to inaccurate heart rate (HR) data, a primary input for EE algorithms. Motion can cause the PPG sensor to lock onto the frequency of repetitive movements (like walking) instead of the cardiac cycle, a phenomenon known as "signal crossover" [26].

- Algorithmic Limitations: Many proprietary algorithms are not transparently validated and are often developed on populations not representative of all end-users (e.g., they may be less accurate for individuals with obesity) [30]. They may also fail to account for different types of physical activity or bodily posture [10].

- Sensor Inherent Error: PPG-based HR measurements are generally less accurate than electrocardiography (ECG). One study found the mean absolute error (MAE) of PPG-based wearables can range significantly, with an average MAE of 9.5 bpm at rest and higher errors during activity [26].

- Device-Specific Performance: The accuracy of EE estimation varies substantially between different manufacturers and models, as they use different sensor combinations and proprietary algorithms [10] [26].

2. How does device grade (consumer vs. research) guarantee accuracy? A research-grade designation does not automatically guarantee superior accuracy. One validation study found that a research-grade device did not outperform consumer-grade devices in laboratory conditions and showed low agreement with ECG in ambulatory-like conditions involving movement [31]. The term "research-grade" is a self-designation and does not imply adherence to universal validation standards. Performance must be validated for each specific use case and population.

3. Why are my wearable's EE estimates less accurate for participants with obesity? Individuals with obesity exhibit known differences in walking gait, postural control, and resting energy expenditure [30]. Many existing EE algorithms were primarily developed and validated in non-obese populations, leading to systematic errors when applied to individuals with obesity. Hip-worn devices can be further affected by biomechanical differences and device tilt angle, though wrist-worn devices also face challenges and require specifically tailored algorithms for this population [30].

4. How does low calorie intake or resting states exacerbate overestimation? During periods of low calorie intake or sedentary behavior, the absolute energy expenditure is low. In these contexts, the relative impact of any systematic error in the device's algorithm or sensors becomes magnified. For instance, an absolute error of 20-30 kcal might represent a small percentage of error during vigorous exercise but a very large percentage during rest or low-intensity activities, leading to significant overestimation of total daily energy expenditure [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: High Variance in EE Data During Ambulatory Studies

Potential Cause: Motion artifacts corrupting PPG signals and over-reliance on accelerometry data that doesn't capture the full picture of energy cost.

Solution Steps:

- Implement a Signal Qualifier: Use a signal quality indicator to filter out periods of poor PPG signal. One study in cardiac patients used a qualifier that improved heartbeat detection accuracy within 100 ms to 98.2% (from 94.6%) [32]. Discard data segments with low-quality signals from your analysis.

- Fuse Sensor Data Cautiously: Leverage device agnostic approaches that use raw accelerometry and HR data, as this has been shown to predict physical activity energy expenditure (PAEE) comparably to research-grade devices in some models [33]. However, be aware that the primary source (PPG) may already be flawed.

- Segment Activity Types: Analyze EE data by specific activity type (e.g., walking, sitting, standing) rather than aggregating all data. Accuracy can vary significantly across different activities [10] [26].

Problem 2: Systematic Overestimation of EE in Specific Populations

Potential Cause: The algorithms used by the wearable device are not validated for your study population (e.g., individuals with obesity, specific ethnic groups, or clinical patients).

Solution Steps:

- Validate Against a Criterion in Your Cohort: Before main data collection, conduct a sub-study validating the wearable device against a criterion measure (like indirect calorimetry) within your specific population [10] [30].

- Use Population-Specific Algorithms: If possible, develop or apply machine learning models trained on your target population. One study developed a new BMI-inclusive algorithm that provided more reliable EE measures for people with obesity compared to 11 other algorithms [30].

- Report Device and Algorithm Details: Always report the specific device model, firmware version, and the name of the algorithm used (e.g., "Kerr et al.'s method" [30]) in your methods section to ensure reproducibility.

Problem 3: Poor Heart Rate Data Quality Affecting EE Estimates

Potential Cause: The PPG sensor is failing to get a clean signal due to motion, fit, or skin properties.

Solution Steps:

- Ensure Proper Fit: Verify the device is snug but comfortable on the wrist. The sensor should maintain consistent contact with the skin.

- Optimize Placement: Follow the manufacturer's instructions for placement. Some studies randomize the wrist (dominant/non-dominant) and specific position to control for placement variables [10].

- Contextualize with Activity Logs: Correlate periods of high HR error with activity logs. Error is typically higher during physical activity than at rest [26]. Consider using a chest-strap ECG as a gold-standard reference in a subset of participants to quantify the device-specific error in your study setting [31].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

To ensure the reliability of your data, validating wearable devices against gold-standard measures within your specific experimental setup is crucial.

Protocol 1: Validating EE Estimation in Laboratory Conditions

This protocol is designed to benchmark a wearable device against indirect calorimetry under controlled activity intensities.

1. Criterion Measure:

- Instrument: COSMED K5 or similar portable gas analysis system [10] [30].

- Calibration: Warm up the device for at least 15 minutes and calibrate with high-grade calibration gases and a 3 L calibration syringe before each session [10].

2. Index Device(s):

- Test Devices: Commercial smartwatches (e.g., Apple Watch, Garmin, Fitbit) or research-grade wearables.

- Initialization: Input participant height, weight, gender, and date of birth into the watch settings as required [10].

- Placement: Place watches on the wrist according to the manufacturer's instructions. To counterbalance, use a randomization list to assign which watch is on which wrist for different participants [10].

3. Participant Preparation:

- Instruct participants to fast for at least 6 hours (water only), avoid caffeine and stimulants, and abstain from vigorous activity and alcohol for 24 hours prior [10].

- Measure anthropometrics (height, weight, body composition) prior to testing.

4. Experimental Protocol:

- Activities: Have participants perform a series of activities of varying intensities. A typical protocol may include:

- Data Collection: Simultaneously collect data from the criterion and index devices throughout the protocol.

5. Data Analysis:

- Calculate metrics like Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), Limits of Agreement (LoA) via Bland-Altman analysis, and Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) to compare the wearable's EE estimates to the criterion measure [10].

Experimental Workflow for EE Validation

Protocol 2: Evaluating Sensor Performance Across Skin Tones

This protocol systematically assesses the impact of skin tone on PPG accuracy, a critical factor for inclusive study design.

1. Criterion Measure:

- Instrument: ECG patch (e.g., Bittium Faros 180) as the gold standard for heart rate [26].

2. Index Device(s):

- Test Devices: A selection of consumer- and research-grade PPG wearables.

3. Participant Recruitment:

- Recruit a cohort of participants that equally represents all skin tone types according to the Fitzpatrick (FP) scale [26].

4. Experimental Protocol:

- Conditions: Have each participant complete a protocol while wearing the ECG and multiple wearables (in sequential rounds to avoid interference). The protocol should include:

- Seated rest (baseline)

- Paced deep breathing

- Physical activity (e.g., walking to increase HR)

- Seated rest (recovery)

- A non-physical stressor (e.g., typing task, arithmetic task) [26].

- Data Collection: Record HR and PPG data from all devices throughout.

5. Data Analysis:

- Calculate Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Mean Directional Error (MDE) for HR measurements for each device, stratified by Fitzpatrick skin tone group and activity condition [26].

- Use mixed effects statistical models to examine the relationship between error and skin tone, device, and activity condition.

Table 1: Accuracy of Smartwatch EE Estimation During Outdoor Ambulation (vs. Indirect Calorimetry) [10]

| Device | Activity | Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) | Limits of Agreement (LoA) in kcal | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apple Watch Series 6 | Walking (6 km/h) | 19.8% | 44.1 | 0.821 |

| Running (10 km/h) | 24.4% | 62.8 | 0.741 | |

| Garmin Fenix 6 | Walking (6 km/h) | 32.0% | 150.1 | 0.216 |

| Running (10 km/h) | 21.8% | 89.4 | 0.594 | |

| Huawei Watch GT 2e | Walking (6 km/h) | 9.9% | 48.6 | 0.760 |

| Running (10 km/h) | 11.9% | 65.6 | 0.698 |

Table 2: PPG Heart Rate Accuracy Across Conditions (vs. ECG) [31] [26]

| Condition | Typical Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Resting State | ~9.5 bpm (average across devices) [26] | Research-grade devices do not consistently outperform consumer-grade in lab settings [31]. |

| Physical Activity | ~30% higher error than at rest [26] | Accuracy deteriorates with motion; devices may lock onto movement frequency (signal crossover) [26]. |

| Across Skin Tones | No statistically significant difference in accuracy found [26] | Significant device-to-device differences and activity-type dependencies are larger drivers of error [26]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Equipment for Validating Wearable Sensor Data

| Item | Function in Research | Example Products / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Portable Metabolic Cart | Criterion Measure for EE. Provides breath-by-breath measurement of oxygen consumption (VO₂) and carbon dioxide production (VCO₂) to calculate Energy Expenditure via indirect calorimetry. | COSMED K5 [10] [30] |

| Ambulatory ECG Monitor | Criterion Measure for Heart Rate. Provides gold-standard data for validating PPG-based heart rate and heart rate variability (HRV) from wearables. | Bittium Faros 180 [26], VU-AMS [31] |

| Research-Grade Accelerometer | Criterion for Motion Capture. Provides high-fidelity raw accelerometry data for activity classification and validating commercial device accelerometers. | ActiGraph GT9X [33] [30] |

| Body Composition Analyzer | Participant Characterization. Precisely measures body fat percentage and BMI, which are critical covariates for EE algorithm development and validation. | InBody 720 [10] |

| Wearable Camera | Ground Truth for Behavioral Context. Provides visual confirmation of activity type and posture in free-living validation studies, enabling accurate annotation of sensor data. | Used in free-living study protocols [30] |

Signal Crossover in PPG Sensors During Motion

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: What is the primary evidence that wearable devices overestimate calorie intake in low intake scenarios?

A1: A 2020 validation study of a wearable nutrition tracking wristband provides direct evidence. The research employed a reference method where all meals were prepared, calibrated, and served at a campus dining facility, with energy and macronutrient intake precisely recorded. The Bland-Altman analysis revealed a mean bias of -105 kcal/day, indicating a tendency to overestimate at lower calorie intake levels and underestimate at higher intakes. The 95% limits of agreement were very wide (between -1400 and 1189 kcal/day), demonstrating high variability and significant potential for overestimation in research contexts focusing on low energy intake [11].

Q2: Why are proprietary algorithms a source of bias in nutritional wearables research?

A2: Proprietary algorithms introduce bias through several mechanisms, primarily due to a lack of transparency and validation in key areas:

- Lack of Transparency: The algorithms that convert sensor data into calorie expenditure estimates are "black boxes," meaning their internal logic and validation metrics are not available for scientific scrutiny [30].

- Exclusion of Diverse Populations: Many algorithms are developed and validated on homogenous populations (e.g., young, healthy, normal BMI), leading to systematic errors when applied to groups with different physiologies, such as individuals with obesity [34] [30]. A 2025 study specifically highlighted the need for BMI-inclusive algorithms to ensure reliability across diverse body types [30].

- Inadequate Real-World Validation: The complex process of transforming food into bioavailable energy is affected by interindividual differences in metabolism, gastrointestinal health, and meal composition. Proprietary algorithms often fail to account for this complexity, leading to discrepancies between measured intake and actual bioavailable energy [11].

Q3: What are the practical consequences of this algorithmic bias for clinical or research settings?

A3: The consequences are significant and can compromise research integrity and participant safety.

- Inaccurate Data: Reliance on biased data can lead to flawed conclusions in studies investigating the efficacy of nutritional or pharmaceutical interventions.

- Health Risks: Systematic overestimation of calorie intake could lead to inappropriate dietary recommendations, potentially exacerbating conditions the research aims to treat. Furthermore, inaccurate heart rate data (a key input for calorie algorithms) can mislead participants about their exercise intensity, potentially jeopardizing their safety during physical activity [35].

- Reinforcement of Health Disparities: If algorithms are not validated across diverse racial, ethnic, and body composition groups, the research outcomes can perpetuate existing health disparities and provide ineffective solutions for underrepresented populations [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: How to Identify and Mitigate Algorithmic Bias in Your Wearables Data

Follow this workflow to diagnose and address potential bias from proprietary algorithms in your research data.

Procedural Steps:

- Check Device Validation Literature: Before designing your study, investigate peer-reviewed publications that have independently validated the specific wearable device you plan to use. Look for studies that report metrics like Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) and Bland-Altman limits of agreement against a gold standard. For example, one study found a consumer tracker had a MAPE of 29.3% for calorie expenditure versus a metabolic analyzer [36].

- Conduct a Criterion Validity Check (Sub-Steps 2A-2C):

- 2A. Collect Gold-Standard Data: In a controlled sub-study, measure your outcome variable (e.g., energy expenditure) using an accepted gold-standard method, such as indirect calorimetry (e.g., PNOĒ metabolic analyzer) [36].

- 2B. Collect Device Data Simultaneously: Have participants wear the consumer device while gold-standard data is collected.

- 2C. Perform Bland-Altman Analysis: This statistical method plots the difference between the two measurements against their average. It helps identify systematic bias (e.g., consistent overestimation at low levels) and the limits of agreement, quantifying the expected error range [11].

- Analyze Error Patterns: Examine if the device's error is correlated with participant demographics (age, sex) or activity parameters (speed, intensity). Research shows that factors like speed can have a large effect on the accuracy of some devices [36].

- Stratify Data by Demographic Groups: Separate your data by key demographic variables such as BMI, sex, and skin tone. Analyze the device's accuracy metrics (e.g., MAPE, bias) for each group to check for differential performance, a key indicator of algorithmic bias [34] [30].

- Document Algorithm Limitations: In your research publications, transparently report the known limitations and potential biases of the proprietary algorithms used, citing independent validation studies.

- Implement Statistical Corrections: If a consistent bias pattern is found (e.g., systematic overestimation), you may develop and apply a calibration or correction factor to your dataset, derived from your validity check. Clearly state this procedure in your methods section.

Guide 2: Validating a Wearable Device for Low Calorie Intake/Expenditure Scenarios

This guide provides a detailed methodology to assess a wearable's accuracy specifically in the context of low energy intake, a common scenario in dietary intervention studies.

Experimental Protocol

- Objective: To evaluate the accuracy and bias of a wrist-worn wearable device in estimating energy expenditure under conditions of low calorie intake.

- Design: A cross-sectional laboratory study with a criterion validity component.

- Participants: Recruit a diverse sample that reflects the target population of your broader research, ensuring inclusion of various BMIs, ages, and sexes [34] [30].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function in Experiment | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Portable Metabolic Analyzer (e.g., PNOĒ) | Serves as the criterion measure for energy expenditure (calorie burn) by analyzing respiratory gases [36]. | Ensure it is calibrated according to manufacturer specifications before each testing session. |

| Research-Grade Accelerometer (e.g., ActiGraph wGT3X-BT) | Provides an objective, research-grade measure of physical activity and movement for comparison [36] [30]. | Sample rate should be set consistently (e.g., 30-100 Hz). Placement (hip vs. wrist) should be documented. |

| Fitness Tracker (Device Under Test) | The consumer-grade device whose algorithmic outputs are being validated. | Ensure it is fully charged and set to the correct data recording mode (e.g., sports mode for highest sampling rate) [36]. |

| Treadmill | Provides a controlled environment for administering standardized physical activity challenges at varying intensities [36]. | Must be regularly calibrated for speed and incline accuracy. |

Procedure:

- Participant Preparation: Fit participants with the wearable device, the research-grade accelerometer, and the metabolic analyzer according to standardized protocols [36].

- Testing Protocol: Participants will perform a series of activities on a treadmill. The protocol should include:

- Data Collection: For each stage, simultaneously record:

- Energy expenditure from the metabolic analyzer (criterion).

- Calorie expenditure, heart rate, and step count from the wearable device.

- Step count from the research-grade accelerometer.

- Manual step count (hand tally) as a secondary criterion for steps [36].

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) for the wearable's calorie estimate relative to the metabolic analyzer. A MAPE ≤ 3% is considered clinically irrelevant, but values can be much higher (e.g., ~30%) [36].

- Perform Bland-Altman analysis to identify any systematic bias, especially at lower levels of energy expenditure [11].

- Use Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANCOVA) to assess the effect of factors like speed, sex, age, and BMI on the tracker's accuracy [36].

The table below summarizes potential findings and their interpretations based on prior research:

| Observed Result | Possible Interpretation | Action for Researcher |

|---|---|---|

| High MAPE (e.g., >20%) for calorie expenditure [36] | The device's proprietary algorithm has low accuracy for energy estimation. | Use device data with extreme caution; consider it a rough proxy rather than a precise measure. |

| Negative Mean Bias in Bland-Altman plot at low intensity [11] | The device systematically overestimates calorie burn during low-intensity activities, consistent with the core thesis. | Apply a calibration factor for low-intensity data or exclude low-intensity data from analysis. |

| Large 95% Limits of Agreement (e.g., ± 1400 kcal/day) [11] | High variability makes the device unreliable for measuring individual-level intake/expenditure. | The device may only be suitable for analyzing group-level trends, not individual data. |

| Significant effect of BMI on MAPE [30] | The algorithm contains algorithmic bias and performs poorly for individuals with obesity. | Stratify results by BMI or seek a device with a validated, BMI-inclusive algorithm. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Image and Data Capture Issues

Problem: Incomplete or missing food images leading to data loss.

- Potential Cause: Fixed camera orientation and the use of rectangular image sensors can crop out portions of the scene, especially with wide-angle lenses [37]. Body shape, height, and table height variations can cause misalignment [37].

- Solution:

- Consider camera systems that generate circular images to utilize the full circular field of view of the lens, reducing wasted area from 38.9% (4:3 ratio) or 45.6% (16:9 ratio) to near zero [37].

- Implement a mechanical design that allows for camera orientation adjustment to adapt to different wearers [37].

- For chest-worn devices like the eButton, ensure secure placement and check the initial images to verify the field of view adequately captures the eating area [38].

Problem: Poor image quality under low-light conditions, common in free-living settings.

- Potential Cause: Wearable cameras automatically capture images in varying lighting. Low-light conditions in household settings can result in noisy, blurry images that hinder food identification and analysis [39].

- Solution:

- While hardware solutions may be limited, inform participants to eat in well-lit areas when possible to improve image quality for analysis.

- Leverage advanced AI pipelines like EgoDiet, which are specifically optimized to handle challenges such as segmenting food items and containers under suboptimal lighting [39].

Problem: Device signal loss or sensor drop-off during data collection.

- Potential Cause: Transient signal loss from sensor technology or physical issues like the device becoming loose or falling off [11] [38].

- Solution:

Algorithm and Data Processing Issues

Problem: AI model fails to accurately identify culturally unique or mixed dishes.

- Potential Cause: Many AI models are trained on limited food databases that may not represent the diverse culinary practices of all populations, leading to high error rates for specific ethnic cuisines [39] [11].

- Solution:

- Utilize AI systems like EgoDiet:SegNet, which are explicitly optimized for the segmentation of food items and containers in specific cuisines, such as African foods [39].

- For research studies, plan for a manual verification and correction step by trained nutritionists to identify and rectify misclassified foods [40].

Problem: Systematic overestimation of low energy intake and underestimation of high energy intake.

- Potential Cause: This is a known calibration issue with some sensor-based technologies. A study on the GoBe2 wristband found its regression equation was significant, indicating a tendency to overestimate lower calorie intake and underestimate higher intake [11].

- Solution:

- In your analysis, apply a bias-correction formula based on validation studies. For example, the regression equation from one study was Y = -0.3401X + 1963, which can be used to adjust raw device outputs [11].

- Cross-validate device readings with a reference method, such as calibrated study meals, to establish a population- or device-specific calibration curve [11].

Participant and Usability Issues

Problem: Participant concerns about privacy due to continuous image capture.

- Potential Cause: Wearable cameras may passively capture sensitive or personally identifiable information in the background, leading to privacy concerns that affect recruitment and adherence [38] [40].

- Solution:

- Implement strict data handling protocols, including secure storage and the use of automated AI processing to minimize human viewing of images [40].

- Clearly communicate these privacy safeguards during the informed consent process [38].

- Consider privacy-preserving computer vision techniques that extract only relevant features (e.g., portion size, food type) without storing the raw images.

Problem: Low participant adherence to device-wearing protocol.

- Potential Cause: The burden of wearing multiple devices, discomfort, and technical difficulties can lead to non-compliance [38] [40].

- Solution:

- Provide structured support from healthcare providers or research staff to help with device setup and troubleshooting [38].

- Choose devices with a low form factor and high comfort, such as the lightweight eButton [40].

- Gather qualitative feedback on user experience to identify and address specific barriers, which can include issues like skin sensitivity from adhesives or difficulty positioning cameras [38].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ: How accurate are AI and wearable cameras compared to traditional dietary assessment methods? Studies have shown that these novel methods can be competitive with or even outperform traditional methods. The EgoDiet system demonstrated a Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) of 28.0% for portion size estimation in a study in Ghana, which was lower than the 32.5% MAPE observed with the traditional 24-Hour Dietary Recall (24HR) [39]. Another study using the eButton and AI analysis found it could identify many food items that participants failed to record via self-report [40].

FAQ: What are the main technical challenges in passive dietary monitoring? The primary challenges are:

- Data Loss: Ensuring the camera captures a complete view of all food items, which is influenced by hardware design [37].

- Food Identification: Accurately recognizing diverse, mixed, or culturally unique dishes from images, especially with low-quality photos [39] [40].

- Portion Size Estimation: Converting 2D images into accurate 3D volume and weight estimates without standardized reference objects in the frame [39].

- Computational Burden: Automatically processing tens of thousands of images to find the small subset that contains eating events [40].

FAQ: Can these methods capture the actual intake (food consumed) or just the initial portion? This is a key differentiator. Many active methods (e.g., taking a photo with a phone) only capture the initial portion. However, passive wearable cameras like the eButton continuously capture images, allowing them to record both the "before" and "after" states of a meal. This enables the system to estimate the consumed portion size, which is critical for accurate nutrient intake assessment [39].

FAQ: How do you validate the accuracy of a passive dietary monitoring system in a free-living population? The most robust validation involves comparing the system's output against a high-quality reference method. This can include:

- Calibrated Study Meals: Where the energy and nutrient content of all foods served are precisely known and consumption is directly observed by researchers [11].

- Doubly Labeled Water (DLW): Considered a gold standard for measuring total energy expenditure, which can be used to validate estimated energy intake [40].

FAQ: What wearable camera positions are most effective? The two most common and effective positions are:

- Eye-level: Using a device like the Automatic Ingestion Monitor (AIM) clipped to eyeglasses [39].

- Chest-level: Using a device like the eButton pinned onto the shirt [39] [38]. Each position has advantages and limitations regarding field of view and social acceptability, and the optimal choice may depend on the specific research setting and population.

Key Experimental Validation Protocol

This protocol is adapted from studies validating wearable sensors against reference methods [11] [38].

Objective: To validate the accuracy of a wearable device (e.g., eButton, AIM, or sensor wristband) for estimating energy and nutrient intake in a free-living population.

Participants:

- Recruit a sample (e.g., N=25) of free-living adults.

- Apply exclusion criteria for conditions or medications that significantly alter metabolism or digestion [11].

Reference Method:

- Collaborate with a metabolic kitchen or dining facility to prepare and serve all meals for a specified period (e.g., 14 days).

- Use standardized weighing scales to measure the precise weight of each food item served to each participant.

- Researchers directly observe and record any uneaten food to calculate actual consumption.

- All meals are analyzed using a gold-standard food composition database (e.g., USDA FNDDS) to establish "true" intake [11].

Test Method:

- Participants wear the wearable device(s) consistently throughout the test period.

- For cameras, ensure they are activated during all eating occasions.

- Data (images, sensor signals) are processed by the AI pipeline to estimate daily nutritional intake.

Data Analysis:

- Use Bland-Altman analysis to assess the agreement between the reference method and the test method, calculating the mean bias and 95% limits of agreement [11].

- Perform regression analysis to identify any systematic biases (e.g., overestimation at low intakes) [11].

- Calculate metrics like Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) for portion size estimation [39].

Table 1. Performance comparison of AI and wearable cameras against traditional dietary assessment methods.

| Method | Study Context | Performance Metric | Result | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EgoDiet (AI + Wearable Cameras) | London (Ghanaian/Kenyan population) | Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) | 31.9% [39] | Outperformed dietitians' estimates (40.1% MAPE). |

| EgoDiet (AI + Wearable Cameras) | Ghana (African population) | Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) | 28.0% [39] | Showed improved accuracy over 24HR (32.5% MAPE). |

| GoBe2 Wristband | Free-living adults | Mean Bias (Bland-Altman) | -105 kcal/day [11] | Showed systematic error: overestimation at low intake and underestimation at high intake. |

| Remote Food Photography Method (RFPM) | Free-living adults | Underestimate vs. Doubly Labeled Water | 3.7% (152 kcal/day) [40] | Demonstrated accuracy comparable to the best self-reported methods. |

Research Workflow and Signaling Pathway

Dietary Assessment Workflow

Figure 1: This diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow for passive dietary assessment using AI and wearable cameras, from data capture to final report generation.

Technical Pipeline for Portion Estimation

Figure 2: This diagram details the AI pipeline for converting a raw image into a portion size estimate, showing the key technical modules and features involved.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2. Essential hardware, software, and methodologies for research in AI-driven passive dietary monitoring.

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| eButton | Hardware | A chest-pinned wearable camera that passively captures images of meals. Used for feasibility studies in free-living conditions to collect egocentric dietary data [39] [38]. |

| Automatic Ingestion Monitor (AIM) | Hardware | An eye-level wearable camera typically attached to eyeglasses. Used to capture a gaze-aligned view of eating episodes [39]. |

| EgoDiet Pipeline | Software | A comprehensive AI pipeline for segmenting food, estimating container depth and orientation, and ultimately estimating portion size from wearable camera images [39]. |

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) | Hardware | A biosensor that measures interstitial glucose levels. Used alongside wearable cameras to correlate dietary intake with physiological response in metabolic studies [38]. |

| Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) | Methodology | A gold-standard biomarker for measuring total energy expenditure in free-living individuals. Serves as a reference method for validating energy intake estimates from new dietary assessment tools [40]. |

| Calibrated Study Meals | Methodology | Precisely prepared and weighed meals where nutrient content is known. Serves as a high-quality reference method for validating the accuracy of passive monitoring systems in controlled or free-living study designs [11]. |

Integrating Multimodal Data Streams to Improve Caloric Burn Predictions

Frequently Asked Questions