Validating Food Intake via Wearable Device Data: Methods, Challenges, and Applications in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current state and validation of wearable devices for objective food intake monitoring, a critical need in nutritional science and drug development.

Validating Food Intake via Wearable Device Data: Methods, Challenges, and Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current state and validation of wearable devices for objective food intake monitoring, a critical need in nutritional science and drug development. It explores the foundational principles of technologies like bio-impedance sensors, wearable cameras, and accelerometers. The scope extends to methodological applications across research and clinical settings, an examination of technical and practical limitations, and a comparative validation against established standards like Doubly Labeled Water. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes evidence to guide the effective integration of these tools into rigorous scientific practice.

The New Frontier of Dietary Assessment: Core Principles and Technologies in Wearable Monitoring

The Critical Need for Objective Dietary Data in Clinical and Population Research

Accurate dietary intake measurement is foundational to understanding the role of nutrition in human health and disease, yet it remains notoriously challenging to capture accurately and reliably through self-report methods [1]. Traditional dietary assessment tools—including food records, 24-hour recalls, and food frequency questionnaires (FFQs)—are plagued by both random and systematic measurement errors that substantially limit their utility in clinical and population research [1]. These methods rely heavily on participant memory, literacy, motivation, and honesty, introducing biases that cannot be easily quantified or corrected. The pervasive issue of energy underreporting across all self-reported methods further compromises data integrity, with only a limited number of recovery biomarkers (for energy, protein, sodium, and potassium) available to validate reported intakes [1]. As research increasingly links dietary patterns to chronic diseases, the scientific community faces a critical imperative: to transition from error-prone subjective reports to objective, technologically-enabled dietary data collection methods that can capture dietary exposures with greater precision and reliability.

Comparative Analysis of Traditional Dietary Assessment Methods

The selection of an appropriate dietary assessment method depends heavily on the research question, study design, sample characteristics, and target sample size [1]. Each traditional method carries distinct advantages and limitations that researchers must carefully consider when designing nutritional studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional Dietary Assessment Methods

| Method | Time Frame | Primary Applications | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24-Hour Dietary Recall | Short-term (previous 24 hours) | Total diet assessment; cross-sectional studies [1] | Does not require literacy; reduces reactivity by capturing past intake [1] | Relies on memory; requires extensive training; high cost per participant [1] |

| Food Record | Short-term (typically 3-4 days) | Total diet assessment; intervention studies [1] | Captures current intake in real-time; detailed quantitative data [1] | High participant burden; reactivity (changing diet for recording); requires literate/motivated population [1] |

| Food Frequency Questionnaire | Long-term (months to year) | Habitual diet assessment; large epidemiological studies [1] | Cost-effective for large samples; captures usual intake over time [1] | Limited food list; less precise for absolute intakes; relies on generic memory [1] |

| Dietary Screeners | Varies (often prior month/year) | Specific nutrients or food groups [1] | Rapid administration; low participant burden; cost-effective [1] | Narrow focus; requires population-specific development and validation [1] |

Each method produces different types of measurement error. Short-term instruments like 24-hour recalls and food records are subject to within-person variation due to day-to-day fluctuations in dietary intake, requiring multiple administrations to estimate habitual intake [1]. Macronutrient estimates from 24-hour recalls are generally more stable than those of vitamins and minerals, with particularly large day-to-day variability reported for cholesterol, vitamin C, and vitamin A [1]. FFQs aim to capture long-term habitual intake but are limited by their fixed food list and portion size assumptions, making them more suitable for ranking individuals by intake levels rather than measuring absolute consumption [1].

Emerging Wearable Technologies for Objective Dietary Monitoring

Technological advancements have introduced wearable sensors that passively or automatically capture dietary data, minimizing the burden and bias associated with self-report methods. These devices represent a paradigm shift toward objective dietary assessment in free-living settings.

Continuous Glucose Monitors

Continuous Glucose Monitors provide real-time, dynamic glucose measurements that reflect the physiological impact of dietary intake [2]. Originally developed for type 1 diabetes management, CGM technology has expanded to research applications, particularly for understanding postprandial glucose responses to different meal compositions [3]. Modern CGM systems sample glucose levels at regular intervals (e.g., every 5-15 minutes) via a subcutaneous sensor, providing dense temporal data on glycemic excursions [2]. When paired with detailed meal records, CGM data can reveal individual variations in glycemic response to identical meals, enabling personalized nutritional recommendations [2]. Studies have demonstrated that CGM use increases mindfulness of meal choices and motivates behavioral changes, particularly when users receive real-time feedback on how specific foods affect their glucose levels [3].

The eButton and Imaging Devices

The eButton is a wearable device that automatically captures food data through imaging, typically worn on the chest to record meals via photographs taken at regular intervals (e.g., every 3-6 seconds) [3]. The captured images are processed to determine food identification, portion size, and nutrient composition through computer vision algorithms [3]. Research has established the feasibility and acceptability of the eButton in real-life settings, with studies noting its ability to increase user mindfulness of food consumption [3]. Participants in feasibility studies reported that using the eButton made them more conscious of portion sizes and food choices, though some expressed privacy concerns and encountered practical difficulties with camera positioning [3].

Integrated Multimodal Sensing Systems

The most advanced approach combines multiple sensors to capture complementary dimensions of dietary behavior. The CGMacros dataset exemplifies this integrated approach, containing synchronized data from two CGM devices (Abbott FreeStyle Libre Pro and Dexcom G6 Pro), a Fitbit activity tracker, food photographs, and detailed macronutrient information [2]. This multimodal framework enables researchers to analyze relationships between dietary intake, physiological responses, and physical activity in a comprehensive manner. The dataset includes 45 participants (15 healthy, 16 pre-diabetes, 14 type 2 diabetes) who consumed meals with varying and known macronutrient compositions over ten consecutive days in free-living conditions [2]. Such rich, multimodal datasets are essential for developing machine learning approaches to automated diet monitoring and personalized nutrition recommendations.

Table 2: Wearable Device Performance in Dietary Research

| Device Type | Primary Data Collected | Research Applications | Participant Experience | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitor | Interstitial glucose measurements every 5-15 minutes [2] | Postprandial glucose response analysis; meal composition estimation [2] | Increases meal choice mindfulness; may cause skin sensitivity; sensors can detach [3] | Requires structured support from healthcare providers for data interpretation [3] |

| eButton | Food images every 3-6 seconds during meals [3] | Food identification; portion size estimation; nutrient analysis [3] | Increases dietary awareness; raises privacy concerns; positioning can be challenging [3] | Computer vision algorithms needed for image analysis; privacy protections essential [3] |

| Activity Trackers | Heart rate; metabolic equivalents; movement [2] | Energy expenditure estimation; contextualizing dietary effects [2] | Generally well-tolerated; provides holistic health picture | Data integration challenges with other sensor systems |

Experimental Protocols for Dietary Assessment Studies

Protocol: Multimodal Dietary Data Collection

The CGMacros study provides a robust methodological framework for collecting objective dietary data in free-living populations [2]. This protocol can be adapted for various research contexts investigating diet-health relationships:

Participant Screening and Recruitment: Recruit participants representing target health statuses (healthy, pre-diabetes, type 2 diabetes). Exclusion criteria should include medications that significantly impact glucose metabolism (e.g., insulin, GLP-1 receptor agonists) to reduce confounding variables [2].

Baseline Data Collection: Collect comprehensive baseline measures including:

- Demographic information (age, gender, race/ethnicity)

- Anthropometric measurements (height, weight, BMI)

- Blood analytics (HbA1c, fasting glucose, insulin, lipid profile)

- Gut microbiome profiles via stool samples [2]

Sensor Deployment: Equip participants with:

- Two CGM devices placed on upper arm and abdomen (e.g., Abbott FreeStyle Libre Pro and Dexcom G6 Pro)

- Chest-worn eButton for meal imaging

- Wrist-worn activity tracker (e.g., Fitbit Sense) [2]

Dietary Intervention Protocol: Implement a structured yet free-living dietary protocol:

- Provide standardized breakfasts and lunches with varying macronutrient compositions

- Allow self-selected dinners to increase ecological validity

- Mandate minimum 3-hour intervals between meals to isolate postprandial responses

- Instruct participants to capture food photographs before and after consumption [2]

Data Integration and Processing:

- Synchronize timestamps across all devices

- Interpolate CGM data to uniform sampling rate (e.g., 1-minute intervals)

- Link meal macronutrient data with CGM traces at corresponding timestamps

- Extract meal timestamps from food photographs [2]

Protocol: Cultural Adaptation for Diverse Populations

Research with Chinese Americans with type 2 diabetes demonstrates the importance of culturally adapted protocols [3]:

Culturally Sensitive Recruitment: Partner with community organizations; utilize culturally appropriate communication channels; offer materials in relevant languages.

Cultural Meal Considerations: Account for culturally significant foods (e.g., rice, noodles) when analyzing dietary patterns; recognize communal eating practices; understand cultural norms around food offerings and hospitality [3].

Technology Training: Provide comprehensive device orientation with language-appropriate materials; address privacy concerns common in certain cultural contexts; offer ongoing technical support [3].

Data Interpretation Framework: Contextualize findings within cultural dietary patterns; engage cultural informants in data analysis; recognize that Western dietary recommendations may conflict with traditional eating practices [3].

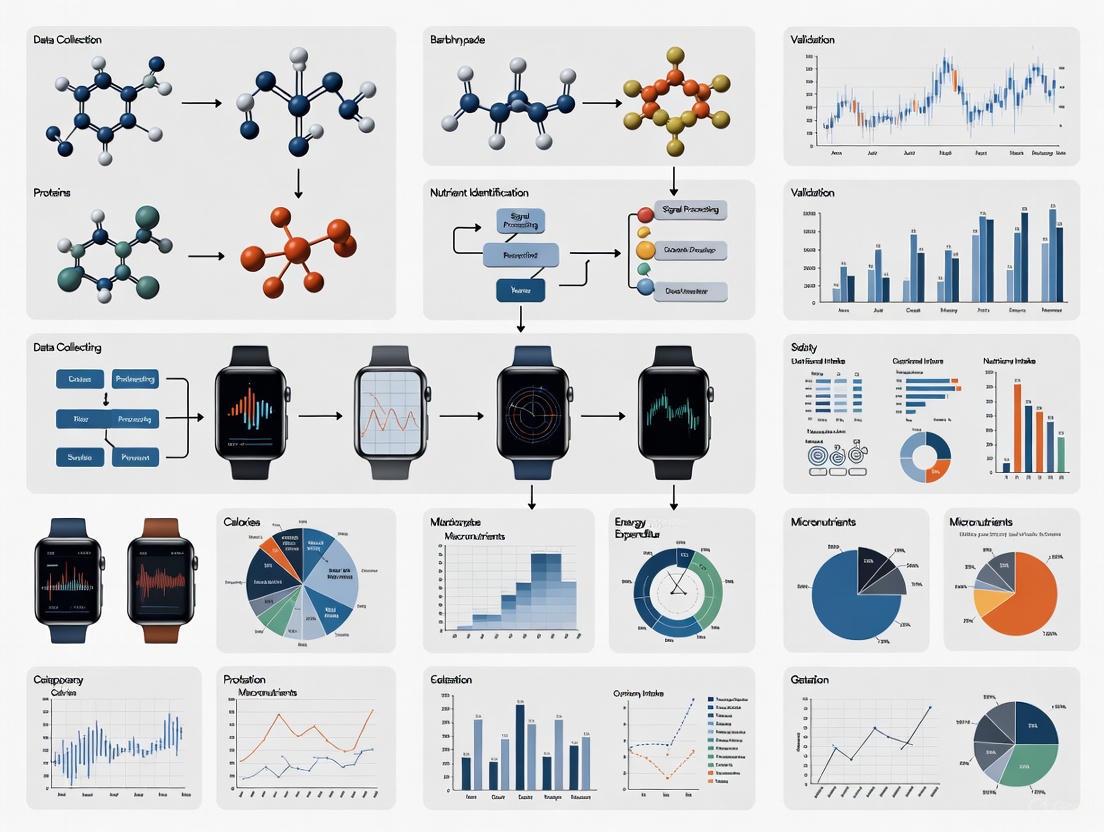

Visualizing Methodological Frameworks

Diagram 1: Multimodal Dietary Assessment Workflow

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Dietary Assessment Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Products/Models | Research Function | Key Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitors | Abbott FreeStyle Libre Pro; Dexcom G6 Pro [2] | Measures interstitial glucose concentrations at regular intervals | Sampling periods: 15-min (Libre Pro), 5-min (Dexcom); 10-14 day wear period [2] |

| Wearable Cameras | eButton [3] | Automatically captures food images during eating episodes | Image capture frequency: 3-6 seconds; chest-mounted positioning [3] |

| Activity Trackers | Fitbit Sense [2] | Quantifies physical activity and energy expenditure | Metrics: heart rate, metabolic equivalents, step count, minute-by-minute data [2] |

| Diet Tracking Software | MyFitnessPal [2] | Logs food intake and estimates nutrient composition | Database: extensive food database with macronutrient and micronutrient data [2] |

| Data Processing Tools | Custom Python/R scripts; Viome microbiome kit [2] | Processes multimodal data; analyzes biological samples | Functions: data synchronization, interpolation, microbiome sequencing [2] |

Data Integration and Analysis Approaches

The true potential of objective dietary assessment emerges through sophisticated integration of multimodal data streams. Research demonstrates that combining CGM data with meal information enables machine learning approaches to estimate meal macronutrient content based on the shape of postprandial glucose responses [2]. This is possible because postprandial glucose responses depend not only on carbohydrate content but also on the amounts of protein and fat in a meal [2].

Temporal alignment of data sources is critical for meaningful analysis. The CGMacros dataset exemplifies best practices through:

- Linear interpolation of CGM data to create uniform one-minute sampling intervals

- Extraction of meal timestamps from food photographs

- Calculation of metabolic equivalents from activity tracker data using mean filtering with 20-minute windows [2]

This integrated approach enables researchers to analyze precise temporal relationships between dietary intake, physiological responses, and physical activity patterns, creating a comprehensive picture of diet-health interactions in free-living contexts.

The limitations of traditional self-reported dietary assessment methods necessitate a paradigm shift toward objective, technology-enabled approaches. Wearable devices like continuous glucose monitors and automated food imaging systems offer promising alternatives that minimize recall bias and participant burden while generating rich, multimodal datasets. The integration of these technologies—capturing dietary intake, physiological responses, and physical activity simultaneously—provides unprecedented opportunities to understand complex diet-health relationships in free-living populations. As these methodologies advance, they promise to enhance the precision of nutritional epidemiology, strengthen the evidence base for dietary guidelines, and ultimately support more effective, personalized nutrition interventions for disease prevention and management.

Accurately validating food intake represents a significant challenge in nutritional science, clinical research, and drug development. Traditional methods like 24-hour dietary recalls and food diaries are plagued by subjectivity, with under- or over-reporting compromising data integrity [4]. The emergence of wearable sensors offers a paradigm shift toward objective, passive monitoring of dietary intake and its physiological effects. This guide provides a systematic comparison of two dominant technological approaches: wearable bio-impedance sensors and egocentric wearable cameras. We objectively evaluate their operational principles, performance metrics, and experimental validation to inform researcher selection and implementation.

The technological landscape for food intake validation is broadly divided into two categories: physiological response monitors (e.g., bio-impedance sensors) that measure the body's reaction to nutrient intake, and direct intake capturers (e.g., wearable cameras) that document food consumption visually. The table below summarizes their core characteristics, capabilities, and limitations.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Wearable Technologies for Food Intake Validation

| Feature | Wearable Bio-Impedance Sensors | Wearable Cameras (Egocentric Vision) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Infers intake by measuring physiological fluid/electrolyte shifts [5] | Directly captures food consumption events and estimates portion size via image analysis [6] |

| Measured Parameters | Bioelectrical impedance (Resistance, Reactance), Phase Angle, calculated energy intake [7] [5] | Food container geometry, food region ratio, camera-to-container distance, portion weight [6] |

| Key Outputs | Estimated caloric intake, macronutrient grams, body water compartments [5] | Identified food types, portion size estimation (weight/volume), eating timing and sequence [6] |

| Reported Accuracy (vs. Reference) | High variability: Mean bias of -105 kcal/day vs. controlled meals; wide limits of agreement [5] | MAPE of 28.0-31.9% for portion size vs. dietitian assessment or 24HR [6] |

| Primary Advantage | Passive, provides data on metabolic response | Moves closer to "ground truth" of intake; records contextual eating behaviors [6] |

| Inherent Limitations | Signal loss; over/under-estimation at intake extremes; assumes standard hydration [5] | Privacy concerns; computational complexity; challenges with mixed dishes and low-light conditions [6] |

Deep Dive: Wearable Bio-Impedance Sensing

Operational Principles and Signaling Pathways

Bio-impedance sensors for nutritional intake estimation function on the principle that the consumption and absorption of nutrients, particularly glucose, cause measurable shifts in body fluid compartments between extracellular (ECW) and intracellular (ICW) spaces. A low-level, alternating current is passed through tissues, and the opposition to this flow (impedance, Z) is measured. Impedance comprises Resistance (R), primarily from extracellular fluids, and Reactance (Xc), related to cell membranes' capacitive properties [7] [8]. The Phase Angle (PhA), derived from the arc tangent of the Xc/R ratio, serves as an indicator of cellular integrity, fluid status, and nutritional status [7]. Algorithms then convert the temporal patterns of these fluid shifts into estimates of energy intake and macronutrient absorption [5].

Diagram: Bio-Impedance Signaling Pathway for Nutrient Intake Estimation

Experimental Protocol for Validation

A typical protocol for validating a bio-impedance-based nutrient intake monitor involves tightly controlled meal conditions and comparison against a rigorous reference method [5].

- Objective: To evaluate the accuracy and precision of a wearable bio-impedance device in estimating daily energy intake in free-living participants under controlled meal conditions.

- Population: Adult participants (e.g., n=25), screened for absence of chronic metabolic disease, weight stability, and not on restricted diets [5].

- Reference Method: Collaboration with a metabolic kitchen to prepare and serve calibrated study meals. All food is weighed, and its energy/macronutrient content is calculated using established databases. Participants consume meals under direct observation to ensure 100% reporting accuracy for intake [5].

- Test Method: Participants wear the bio-impedance device (e.g., a wristband) continuously over the validation period (e.g., two 14-day periods). The device operates passively to collect data [5].

- Data Analysis: Comparison of daily energy intake (kcal/day) from the reference method versus the device output using Bland-Altman analysis to determine mean bias and limits of agreement [5].

Deep Dive: Wearable Camera Systems (Egocentric Vision)

Operational Principles and Computational Workflow

Wearable cameras like the EgoDiet system approach dietary assessment by passively capturing first-person (egocentric) images. The core innovation lies in its multi-module AI pipeline that automates the conversion of images into portion size estimates, minimizing human intervention [6].

- EgoDiet:SegNet: Utilizes a Mask R-CNN backbone to segment food items and their containers from the image, which is crucial for subsequent analysis [6].

- EgoDiet:3DNet: A depth estimation network that reconstructs 3D models of the containers and estimates camera-to-container distance, obviating the need for expensive depth-sensing cameras [6].

- EgoDiet:Feature: An extractor that derives portion size-related features from the previous modules. Key indicators include the Food Region Ratio (FRR), which is the proportion of the container region occupied by a specific food, and the Plate Aspect Ratio (PAR), which helps estimate the camera's tilting angle [6].

- EgoDiet:PortionNet: The final module that estimates the consumed portion size in weight. It leverages the extracted features to solve a "few-shot regression" problem, as large-scale, manually weighed food datasets are rare [6].

Diagram: Wearable Camera Dietary Analysis Computational Workflow

Experimental Protocol for Validation

The validation of a passive wearable camera system is typically conducted in field studies comparing its performance against trained dietitians or traditional methods [6].

- Objective: To assess the accuracy of a wearable camera pipeline (EgoDiet) for portion size estimation in free-living or community settings.

- Population: Field studies conducted in specific populations (e.g., of Ghanaian and Kenyan origin) to test robustness across diets [6].

- Reference Method: In one study design, dietitians' assessments of portion size from images can serve as one benchmark. Another common reference is the traditional 24-hour dietary recall (24HR) interview [6].

- Test Method: Participants wear a low-cost, wearable camera that automatically captures images throughout the day, including eating episodes. The EgoDiet pipeline processes these images automatically [6].

- Data Analysis: The primary outcome is the Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) for portion size estimation. The MAPE of the EgoDiet system (e.g., 28.0%) is directly compared to the MAPE of dietitians (e.g., 40.1%) or the 24HR method (e.g., 32.5%) [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for Wearable Food Intake Validation Research

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Multi-Frequency BIA (MFBIA) Device (e.g., InBody 770) | Provides segmental body composition analysis and raw parameters like Resistance (R) and Reactance (Xc) at multiple frequencies, offering detailed fluid compartment data [8]. |

| Tetrapolar Bioimpedance Analyzer (e.g., InBody S10) | Uses a standardized 8-point tactile electrode system to measure whole-body and segmental Phase Angle, a key indicator of cellular health and hydration [7]. |

| Low-Cost Wearable Camera | The core hardware for egocentric vision systems; passively captures first-person-view image data for automated dietary analysis in free-living conditions [6]. |

| Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry (DXA) | Serves as a reference method for validating body composition measures (Fat Mass, Fat-Free Mass) from BIA devices in validation studies [9] [8]. |

| Controlled Meal Kits | Pre-portioned, nutritionally calibrated meals used as a gold standard to validate the energy and macronutrient output of bio-impedance devices against known intake [5]. |

| 24-Hour Dietary Recall (24HR) | A traditional, interview-based dietary assessment method used as a comparative benchmark for validating new technologies like wearable cameras [6]. |

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) | Often used in conjunction with other sensors to provide correlative data on metabolic response to food intake, helping to triangulate nutrient absorption timing [5]. |

The choice between bio-impedance and wearable camera technologies is not a matter of selecting a superior option, but of aligning the technology with the research question. Bio-impedance sensors offer a physiological lens, indirectly inferring intake through metabolic changes, making them suitable for studies focused on energy balance and metabolic response. In contrast, wearable cameras provide a behavioral lens, directly observing and quantifying food consumption, which is invaluable for understanding dietary patterns and validating self-reported data. For the most comprehensive picture, future research frameworks may leverage multimodal approaches, integrating data from both sensor types alongside omics analyses to fully characterize the intricate relationships between diet, physiological response, and health outcomes [10] [4].

Accurately assessing dietary intake and eating behavior is fundamental to understanding their role in chronic diseases like obesity, type 2 diabetes, and heart disease [11] [12]. Traditional methods, such as 24-hour dietary recalls and food diaries, rely on self-reporting and are prone to significant memory bias, under-reporting, and participant burden [13] [12]. For instance, large dietary surveys have found that 27% to 38% of 24-hour food intake recalls are implausible when compared to objective measures like doubly-labeled water [13]. Wearable sensor technology presents a transformative opportunity to overcome these limitations by enabling the passive, objective, and high-resolution measurement of eating events and nutrient intake in naturalistic settings [11] [12]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the core sensing modalities underpinning these wearable devices, framing them within the broader research thesis of validating food intake via wearable data. It is structured to equip researchers and scientists with a clear understanding of the technological landscape, experimental protocols, and performance characteristics of these emerging tools.

Core Sensing Modalities for Eating Event Detection

Wearable devices detect eating events by monitoring the physiological and physical manifestations of chewing, swallowing, and hand-to-mouth gestures. The primary sensing modalities can be categorized as follows.

Motion and Mechanistic Sensors

These sensors detect the physical movements associated with mastication. Key types include:

- Piezoelectric Strain Sensors: These sensors, often placed on the temporalis muscle, generate a signal in response to the mechanical deformation caused by muscle contraction during chewing [14]. One study used an LDT0-028K sensor from Measurement Specialties, placed on the left temporalis muscle, sampling data at 1 kHz [14].

- Accelerometers and Gyroscopes: Typically embedded in wrist-worn devices or headsets, these sensors detect the characteristic motion patterns of biting, chewing, and hand-to-mouth gestures [11] [12]. They are among the most common sensors used in multi-sensor systems for in-field eating detection [11].

- Piezoresistive Bend Sensors: These flexible sensors can be attached to eyeglass frames. Their resistance changes in response to bending caused by the contraction of the temporalis muscle during chewing [14]. A study utilizing a Spectra Symbol 2.2” sensor on the right temple of eyeglasses sampled data at 128 Hz [14].

Acoustic Sensors

Acoustic sensing captures the sounds of mastication and swallowing, typically via a microphone placed in or near the ear [12]. While highly sensitive, this method can be susceptible to ambient noise. Chewing sounds captured through an earpiece have been successfully used to develop automatic chewing detection for monitoring food intake behavior [14].

Physiological and Biometric Sensors

This category measures the physiological changes that occur during eating.

- Surface Electromyography (sEMG): sEMG involves placing electrodes directly on the skin overlying masticatory muscles (e.g., the temporalis or masseter). It measures the electrical activity associated with muscle contraction during chewing [14].

- Ear Canal Pressure Sensors: This novel approach leverages the physical deformation of the ear canal during jaw movement. An air pressure sensor (e.g., SM9541) is housed in a custom-molded earbud. The grinding motion of the jaw during chewing causes the ear canal to expand and contract, producing measurable pressure changes [14]. A published protocol sampled this data at 128 Hz [14].

Table 1: Comparison of Wearable Sensor Modalities for Eating Event Detection

| Sensing Modality | Measured Parameter | Common Placement | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piezoelectric Strain [14] | Temporalis muscle movement | Skin surface (temporalis) | Direct measure of muscle activity; High sensitivity | Susceptible to motion artifact; Requires skin contact |

| Accelerometer [11] [12] | Jaw and hand/arm motion | Wrist, head, neck | Ubiquitous in consumer devices; Good for gesture detection | Less specific to chewing; Confounded by other activities |

| Acoustic (Microphone) [14] [12] | Chewing/swallowing sounds | Ear canal, neck | High specificity to eating sounds | Privacy concerns; Affected by background noise |

| sEMG [14] | Muscle electrical activity | Skin surface (masseter/temporalis) | Direct measure of muscle activation | Can be obtrusive; Sensitive to sweat and electrode placement |

| Ear Canal Pressure [14] | Ear canal deformation | Ear canal | Passive and less obtrusive than some methods | Requires individual earbud molding; Novel, less validated |

Technical Workflow for Eating Event Detection

The following diagram illustrates the generalized signal pathway and data processing workflow for detecting eating events from sensor data.

Diagram 1: Signal processing workflow for eating event detection.

Sensing Modalities for Nutrient and Food Intake Assessment

Moving beyond mere eating event detection, more advanced technologies aim to identify the type and quantity of food consumed.

Egocentric (Wearable) Cameras

Wearable cameras capture first-person-view images of food before, during, and after consumption. Computer vision and deep learning algorithms then analyze these images to identify food items and estimate portion sizes.

- Active Capture vs. Passive Capture: Active methods require the user to manually capture images (e.g., with a smartphone), while passive methods use wearable cameras (e.g., the eButton or AIM) that automatically capture images at set intervals [15] [16]. Passive methods are less burdensome and can capture eating context and sequence [15].

- The EgoDiet Pipeline: This is an example of a comprehensive, vision-based dietary assessment system. It involves several modules [15]:

- EgoDiet:SegNet: Segments food items and containers in images.

- EgoDiet:3DNet: Estimates camera-to-container distance and reconstructs 3D container models.

- EgoDiet:Feature: Extracts portion size-related features like Food Region Ratio (FRR) and Plate Aspect Ratio (PAR).

- EgoDiet:PortionNet: Estimates the final portion size (weight) of the food consumed.

Integration with Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGM)

While not a direct nutrient sensor, CGM is a critical wearable technology for validating the metabolic impact of food intake. CGMs measure interstitial glucose levels in near-real-time, providing an objective physiological correlate of carbohydrate intake [17] [16]. When paired with dietary intake data from cameras or other sensors, CGM data can help researchers understand individual glycemic responses to specific foods and meals [16].

Table 2: Comparison of Nutrient Assessment Modalities

| Technology | Measured Parameter | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wearable Camera (eButton) [15] [16] | Food images for type/volume | Passive capture; Provides rich contextual data | Privacy concerns; Complex data processing | MAPE for portion size: 28.0%-31.9% [15] |

| AI & Computer Vision (EgoDiet) [15] | Food type and portion size | Reduces error vs. 24HR; Automated analysis | Requires specialized algorithms | Outperformed dietitians' estimates (31.9% vs 40.1% MAPE) [15] |

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) [17] [16] | Interstitial glucose levels | Objective metabolic data; Real-time feedback | Measures response, not intake; Cost | Validated for clinical use; improves time-in-range [17] |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Robust experimental design is crucial for validating the performance of wearable eating sensors. Below are detailed methodologies from key studies.

Protocol: Validation of Chewing Strength Sensors

A foundational study evaluated four wearable sensors for estimating chewing strength in response to foods of different hardness (carrot, apple, banana) [14].

- Participants: 15 healthy volunteers.

- Sensors Deployed Simultaneously: 1) Ear canal pressure sensor, 2) Piezoresistive bend sensor on eyeglass temple, 3) Piezoelectric strain sensor on temporalis, 4) sEMG on temporalis.

- Food Procedure: Each participant consumed 10 bites of carrot, apple, and banana. Food hardness was objectively measured with a penetrometer.

- Data Analysis: Single-factor ANOVA was used to test the effect of food hardness on the standard deviation of sensor signals, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test (5% significance level).

- Key Result: A significant effect of food hardness was found for all four sensors (p < .001), confirming their ability to distinguish chewing strength related to food texture [14].

Protocol: In-Field Eating Detection

A scoping review highlighted methods for validating wearable sensors in free-living conditions [11].

- Sensors: 65% of reviewed studies used multi-sensor systems, with accelerometers being the most common (62.5%).

- Ground Truth: All studies used a ground-truth method for validation. This included self-report (e.g., food diaries) and objective methods (e.g., video recording).

- Evaluation Metrics: The most frequently reported metrics were Accuracy and F1-score, though there is significant variation in reporting standards across the field [11].

Protocol: Validation of the "Feeding Table" UEM

A novel Universal Eating Monitor (UEM) was developed to track multiple foods simultaneously [13].

- Apparatus: A table integrated with five high-resolution balances, capable of monitoring up to 12 different foods at once. Data were collected every 2 seconds.

- Validation Experiment: 31 participants underwent a standard meal test over two consecutive days.

- Validation Metrics: Day-to-day repeatability for energy and macronutrient intake was assessed using Pearson correlation (e.g., energy: r = 0.82) and intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) (e.g., energy: ICC = 0.94) [13].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This section details key hardware, software, and analytical tools referenced in the cited experimental research.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Wearable Eating Detection Research

| Item Name | Type | Function/Application | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon Microstructures SM9541 | Sensor | Air pressure sensor for measuring ear canal deformation during chewing. | Used in ear canal pressure sensor system [14] |

| Measurement Specialties LDT0-028K | Sensor | Piezoelectric strain sensor for detecting temporalis muscle movement. | Placed on temporalis muscle [14] |

| Spectra Symbol 2.2" Bend Sensor | Sensor | Piezoresistive sensor for measuring muscle-induced bending of eyeglass temples. | Attached to right temple of eyeglasses [14] |

| eButton / AIM | Device | Wearable, passive cameras for capturing egocentric images of food intake. | Used for dietary assessment in free-living conditions [15] [16] |

| Freestyle Libre Pro | Device | Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) for capturing interstitial glucose levels. | Used to correlate food intake with glycemic response [16] |

| Mask R-CNN | Algorithm | Deep learning backbone for segmenting food items and containers in images. | Used in EgoDiet:SegNet module [15] |

| Universal Eating Monitor (UEM) | Apparatus | Laboratory-scale system with embedded scales for high-resolution tracking of eating microstructure. | "Feeding Table" with multiple balances [13] |

The field of wearable sensing for dietary monitoring has moved beyond simple event detection toward sophisticated, multi-modal systems capable of characterizing both eating behavior and nutrient intake. As the experimental data demonstrates, no single modality is perfect; each has distinct strengths and limitations in terms of accuracy, obtrusiveness, and applicability in field settings [14] [11] [12]. The future of validating food intake via wearable data lies in the intelligent fusion of complementary sensors—such as combining motion sensors for bite detection with cameras for food identification and CGM for metabolic validation [16]. For researchers, the critical challenges remain: improving the accuracy of nutrient estimation, ensuring user privacy (especially with cameras), standardizing validation metrics, and developing robust algorithms that perform reliably in the unstructured complexity of free-living environments [11] [15] [12]. The tools and comparative data presented in this guide provide a foundation for designing rigorous studies that can advance this promising field.

Wearable devices have evolved from simple step-counters to sophisticated health monitoring systems, creating new paradigms for biomedical research and clinical care. These technologies provide an unprecedented opportunity to collect continuous, real-time physiological data in naturalistic settings, moving beyond traditional clinic-based measurements [18] [19]. In the specific context of nutritional science, wearables offer potential solutions to long-standing challenges in dietary assessment, primarily the reliance on self-reported methods that are prone to significant error, bias, and participant burden [20] [21]. This review examines the four key functions of wearable devices—monitoring, screening, detection, and prediction—with a specific focus on their application in validating food intake and eating behaviors, a crucial area for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking objective measures in nutritional research and clinical trials.

Core Functions of Wearable Technology

Wearable devices serve distinct but interconnected functions in health research. Understanding this functional hierarchy is essential for selecting appropriate technologies and interpreting generated data.

Table 1: Core Functions of Wearables in Health Research

| Function | Description | Primary Data Sources | Example in Food Intake Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monitoring [22] | Continuous, passive data collection of physiological and behavioral metrics. | Accelerometers, PPG, ECG, IMUs, cameras [18] [11] | Tracking wrist movements, heart rate, and glucose levels throughout the day. |

| Screening [22] | Identifying at-risk individuals or specific conditions within a monitored population. | Algorithmic analysis of monitored data trends. | Flagging individuals with irregular eating patterns (e.g., night-eating syndrome) from continuous activity data. |

| Detection [22] | Recognizing specific, discrete events or activities from continuous data streams. | Machine learning classifiers applied to sensor data. | Automatically detecting the onset and duration of an eating episode from a combination of arm movement and chewing sounds. |

| Prediction [22] | Forecasting future health states or events based on historical and real-time data. | Predictive algorithms and statistical models. | Predicting postprandial glycemic response based on pre-meal physiology and meal size estimation. |

Monitoring: The Foundation of Data Acquisition

Monitoring is the fundamental, continuous data-collection function that enables all other advanced capabilities. In nutritional research, this involves the passive gathering of data related to eating activity and its physiological consequences. Common monitoring technologies include inertial measurement units (IMUs) to capture hand-to-mouth gestures, photoplethysmography (PPG) to track heart rate variability, and electrocardiography (ECG) for heart rhythm analysis [18]. Emerging tools also include wearable cameras that automatically capture point-of-view images, providing a passive record of food consumption without relying on user memory [21]. The strength of monitoring lies in its ability to capture high-resolution, temporal data in free-living environments, thus providing an ecological momentary assessment that is more reflective of true habitual behavior than self-reports [11] [19].

Screening: Identifying Patterns and Risk

Screening utilizes the data collected through monitoring to identify specific conditions or risk factors within a population. This is often a passive process where algorithms scan for predefined patterns or deviations from normative baselines. For example, in a large-scale public health program, wearable-derived data could be used to screen for populations with consistently high sedentary behavior coupled with frequent snacking patterns [22] [23]. In cardiometabolic health, wearables can screen for atrial fibrillation, a condition that may be influenced by dietary factors like alcohol or caffeine intake [18] [19]. The screening function thus helps researchers and clinicians target interventions and deeper analysis toward individuals who would benefit most.

Detection: Pinpointing Discrete Events

Detection is the function of identifying discrete, specific events from the continuous stream of monitored data. In eating behavior research, this is a primary focus, with studies developing algorithms to detect the exact start and end times of eating episodes. This is typically achieved using multi-sensor systems. For instance, a 2020 scoping review found that 62.5% of in-field eating detection studies used accelerometers to detect distinctive wrist movements associated with biting, while others used acoustic sensors to capture chewing sounds [11]. Detection is more precise than screening, aiming not just to find at-risk individuals, but to log the exact timing and, in some cases, the microstructure (e.g., number of bites, chewing rate) of each eating event.

Prediction: Forecasting Future Outcomes

Prediction represents the most advanced function, using historical and real-time data to infer future health states or events. In the context of nutrition, this could involve predicting an individual's glycemic response to a meal or forecasting the risk of a metabolic syndrome exacerbation based on continuous lifestyle data [22] [23]. For example, one study used wearable data to predict COVID-19 infections days before symptom onset [22] [19]. The predictive function moves from reactive to proactive health management, offering the potential for pre-emptive dietary interventions personalized to an individual's unique physiological response patterns.

Figure 1: The logical relationship between the four key functions of wearables. Monitoring provides the foundational data that feeds into the more complex functions of Screening, Detection, and Prediction.

Application to Food Intake Validation

The validation of food intake via wearable devices is an active and challenging field of research. Traditional methods like food diaries and 24-hour recalls are plagued by misreporting, with under-reporting of energy intake identified in up to 70% of adults in some national surveys [21]. Wearables offer a path toward objective, passive assessment.

Sensor Modalities for Eating Behavior Detection

Multiple sensing approaches are being developed and validated to detect and characterize eating episodes automatically.

Table 2: Wearable Sensor Modalities for Food Intake Assessment

| Sensor Modality | Measured Parameter | Reported Performance | Limitations & Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inertial Sensors (Accelerometer/Gyroscope) [11] [24] | Arm and wrist kinematics (bites, gestures). | Accuracy: 58% - 91.6% (F1-score varies widely) [11] | Confounded by non-eating gestures (e.g., talking, smoking). |

| Acoustic Sensors [11] | Chewing and swallowing sounds. | Can achieve high precision for detection in controlled settings. | Sensitive to background noise; privacy concerns. |

| Photoplethysmography (PPG) [18] | Heart rate, pulse rate variability. | Correlations with glucose absorption; not yet reliable for direct calorie estimation. | Signal noise during movement; proprietary algorithms. |

| Bioelectrical Impedance (BioZ) [18] [20] | Fluid shifts from nutrient/glucose influx. | One study: Mean bias of -105 kcal/day vs. reference, with wide limits of agreement [20]. | High variability; signal loss; requires validation. |

| Wearable Cameras [21] | Image-based food identification and portion size. | Auto-detection of meal images: 50% (snacks) to 95% (meals) [21]. | Privacy, data volume, computational cost for analysis. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Robust validation is critical for translating sensor signals into meaningful dietary data. The following protocols are commonly employed in the field.

1. Laboratory vs. Free-Living Validation: Studies typically start in controlled lab settings to establish proof-of-concept before moving to free-living conditions. Laboratory protocols involve structured activities, including eating standardized meals and performing confounding activities (e.g., talking, gesturing). Sessions are often video-recorded to provide a ground-truth benchmark for validating the sensor-derived eating metrics [25]. For free-living validation, participants wear the devices for extended periods (e.g., 7 days) while going about their normal lives. The ground truth in these settings is often established using a combination of self-report (e.g., food diaries) and objective methods (e.g., continuous glucose monitoring) [20] [11].

2. Reference Method for Caloric Intake: To validate a wearable device claiming to measure energy intake, a rigorous reference method is required. One study collaborated with a university dining facility to prepare and serve calibrated study meals, precisely recording the energy and macronutrient intake of each participant. The wearable's estimates (e.g., from a BioZ wristband) were then compared to this precise reference using statistical methods like Bland-Altman analysis, which revealed a mean bias of -105 kcal/day but with 95% limits of agreement as wide as -1400 to 1189 kcal/day, indicating high variability for individual measurements [20].

3. Multi-Sensor Data Fusion: Given the limitations of single sensors, the most promising approaches involve multi-sensor systems. A common protocol involves simultaneously collecting data from accelerometers (on the wrist), gyroscopes, and acoustic sensors (on the neck or ear). Machine learning models (e.g., support vector machines, random forests) are then trained on this multimodal data to improve the overall accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of eating event detection compared to any single sensor [11].

Figure 2: A generalized experimental workflow for developing and validating wearable-based food intake detection systems, showing the integration of sensor data and ground-truth collection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

For researchers designing studies to validate food intake via wearables, a standard set of tools and reagents is essential.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Wearable Food Intake Studies

| Item | Function & Utility in Research |

|---|---|

| Research-Grade Accelerometers (e.g., ActiGraph LEAP, activPAL) [25] | Provide high-fidelity movement data as a criterion standard for validating consumer-grade device accuracy, especially for detecting eating-related gestures. |

| Consumer-Grade Activity Trackers (e.g., Fitbit Charge, Apple Watch) [23] [25] | The devices under investigation; their data is compared against research-grade devices and ground truth to assess practical applicability. |

| Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGM) [20] [21] | Serve as an objective physiological correlate to food intake, helping to validate the timing and, to some extent, the metabolic impact of eating events. |

| Wearable Cameras (e.g., e-Button, "spy badges") [21] | Provide a passive, image-based ground truth for food presence and type, though they present challenges in data volume and privacy. |

| Bland-Altman Statistical Analysis [20] | A crucial statistical method for assessing the agreement between the wearable device's estimate and the reference method, highlighting bias and limits of agreement. |

| Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) [21] | The gold standard for measuring total energy expenditure in free-living individuals, used to validate the overall accuracy of energy intake estimates over longer periods. |

| Machine Learning Classifiers (e.g., SVM, Random Forest, CNN) [11] [21] | Algorithms required to translate raw sensor data into meaningful eating events (detection) and eventually predictions. |

Comparative Effectiveness in Public Health

The ultimate value of these technologies is their effectiveness in improving health outcomes. Large-scale studies provide critical insights. A 2025 retrospective cohort study (N=46,579) within South Korea's national mobile health care program compared wearable activity trackers to smartphone built-in step counters for reducing metabolic syndrome risk [23]. After propensity score matching, both device types led to significant improvements. Interestingly, the built-in step counter group demonstrated a statistically greater reduction in metabolic syndrome risk (Odds Ratio 1.20, 95% CI 1.05-1.36), with the effect being more pronounced in young adults aged 19-39 (OR 1.35, 95% CI 1.09-1.68) [23]. This highlights that the most complex technology is not always the most effective and that personalization based on user characteristics is key.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite the promise, significant challenges remain. Data quality is highly variable due to differences in sensors and data collection practices [22]. Accuracy of food intake measurement, particularly for caloric and macronutrient content, is not yet reliable for individual-level clinical decision-making, as evidenced by the wide limits of agreement in validation studies [20]. Furthermore, issues of interoperability, health equity, and fairness due to the under-representation of diverse populations in wearable datasets need to be addressed [22].

Future directions point toward the integration of multi-modal data streams (e.g., combining motion, acoustics, and images) using advanced machine learning to create more robust hybrid assessment systems [21]. The field is also moving beyond simple eating detection to characterize meal microstructure, within-person variation in intakes, and food-nutrient combinations within meals, offering a richer understanding of the eating architecture and its link to health [21]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this evolving toolkit offers the potential to integrate objective, continuous dietary metrics into clinical trials and precision health initiatives, transforming our ability to understand and modulate the role of nutrition in health and disease.

From Lab to Real World: Implementing Wearable Dietary Sensors in Research and Clinical Practice

The accurate quantification of food intake is a fundamental challenge in nutritional science, precision health, and pharmaceutical development. Traditional methods, such as 24-hour recalls and food frequency questionnaires, rely on self-reporting and are often unreliable due to human memory limitations and intentional or unintentional misreporting [20] [26]. The emergence of wearable sensor technologies has created new opportunities for objective, passive dietary monitoring. However, single-sensor approaches often capture only isolated aspects of eating behavior, leading to incomplete data. Multi-modal sensor fusion addresses this limitation by integrating complementary data streams from multiple sensors to create a more comprehensive, accurate, and robust understanding of dietary intake [27] [28].

The core principle of sensor fusion is that data from different modalities can be combined to overcome the limitations of individual sensors. In autonomous driving, for instance, multi-sensor fusion integrates cameras, LiDAR, and radar to build a comprehensive environmental model, overcoming the limitations of any single sensor [29]. Similarly, in dietary monitoring, fusing data from acoustic, inertial, bioimpedance, and optical sensors can provide richer insights into eating behaviors, food types, and nutrient intake than any single modality alone [26]. This guide objectively compares the performance of various sensor fusion approaches currently shaping the field of dietary monitoring, with a specific focus on validating food intake via wearable device data.

Comparative Analysis of Sensing Modalities and Fusion Strategies

Classification of Fusion Levels

Multi-modal sensor fusion strategies are systematically categorized based on the stage at which data integration occurs. The table below outlines the three primary levels of fusion, their descriptions, and relevant applications in dietary monitoring.

Table 1: Levels of Multi-Modal Sensor Fusion

| Fusion Level | Description | Advantages | Challenges | Dietary Monitoring Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data-Level (Early Fusion) | Raw data from multiple sensors is combined directly. | Maximizes information retention from original signals. | Highly sensitive to sensor misalignment and synchronization; requires high bandwidth. | Fusing raw audio and inertial signals for chew detection. |

| Feature-Level (Mid-Fusion) | Features are extracted from each sensor's data, then combined into a unified feature vector. | Leverages strengths of different modalities; reduces data dimensionality. | Requires effective cross-modal feature alignment and handling of heterogeneous data. | Combining features from bioimpedance (wrist) and acoustics (neck) for food type classification [30] [26]. |

| Decision-Level (Late Fusion) | Each sensor modality processes data independently to make a preliminary decision; decisions are then fused. | Modular and flexible; resilient to failure of a single sensor. | Potentially loses rich cross-modal correlations at the raw data level. | Combining independent classifications from a wearable camera and an inertial sensor to finalize food intake detection. |

Deep learning has significantly advanced feature-level fusion, with architectures like cross-modal attention mechanisms and transformers enabling the model to learn complex, non-linear relationships between different data streams [28] [29]. Theoretical foundations, such as Bayesian estimation, provide a framework for fusing heterogeneous data and modeling sensor uncertainty, which is critical for real-world applications where sensor noise and failures can occur [29].

Performance Comparison of Dietary Monitoring Technologies

The following table summarizes quantitative performance data for various sensing approaches, highlighting the effectiveness of different modalities and fusion strategies.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Dietary Monitoring Technologies

| Technology / Platform | Sensing Modality | Body Location | Primary Application | Reported Performance | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iEat Wearable [30] | Bioimpedance (2-electrode) | Wrist (one electrode on each) | Food intake activity recognition | Macro F1: 86.4% (4 activities) | Detects cutting, drinking, eating with hand/fork via dynamic circuit changes. |

| iEat Wearable [30] | Bioimpedance (2-electrode) | Wrist (one electrode on each) | Food type classification | Macro F1: 64.2% (7 food types) | Classification based on electrical properties of different foods. |

| GoBe2 Wristband [20] | Bioimpedance + Algorithms | Wrist | Energy intake estimation (kcal/day) | Mean Bias: -105 kcal/day (SD 660) vs. reference | Bland-Altman analysis showed 95% limits of agreement between -1400 and 1189 kcal/day. |

| Feeding Table (UEM) [31] | Multi-load cell scales | Table-integrated | Multi-food meal microstructure | ICC: 0.94 (Energy), 0.90 (Protein) | High day-to-day repeatability for energy and macronutrient intake. |

| Neck-worn Microphone [26] | Acoustic (High-fidelity) | Neck | Food type classification (7 types) | Accuracy: 84.9% | Recognizes intake of fluid and solid foods via chewing and swallowing sounds. |

| Wearable Camera [32] | Optical (Image capture) | Wearable (e.g., on person) | Food and nutrient intake estimation | Methodology Validated | Passive image capture for objective, real-time food intake assessment. |

The data reveals a trade-off between obtrusiveness and granularity of information. Wearable approaches like the iEat system offer passive monitoring but currently achieve more moderate accuracy in complex tasks like food type classification [30]. In contrast, instrumented environments like the Feeding Table provide highly precise, granular data on eating microstructure and macronutrient intake for multiple foods simultaneously, making them invaluable for laboratory validation studies [31].

Experimental Protocols for Validating Food Intake

Validation Study for a Bioimpedance Wristband

A critical validation study assessed the ability of a commercial wristband (GoBe2) to automatically track energy intake in free-living individuals [20].

- Objective: To evaluate the accuracy and practical utility of a wristband sensor for tracking daily nutritional intake (kcal/day) against a controlled reference method.

- Participants: 25 free-living adult participants were recruited, excluding those with chronic diseases, specific diets, or medications affecting metabolism.

- Reference Method: A highly controlled reference method was developed in collaboration with a university dining facility. All meals were prepared, calibrated, and served, with energy and macronutrient intake for each participant meticulously recorded under direct observation by a trained research team.

- Test Method: Participants used the wristband and an accompanying mobile app consistently for two 14-day test periods. The device uses bioimpedance signals to estimate patterns of fluid shifts associated with glucose and nutrient absorption into the bloodstream.

- Data Analysis: A total of 304 daily intake cases were collected. The agreement between the reference method and the wristband was analyzed using Bland-Altman tests. The mean bias was -105 kcal/day (SD 660), with 95% limits of agreement between -1400 and 1189 kcal/day. The regression equation of the plot was Y = -0.3401X + 1963, indicating a tendency for the wristband to overestimate at lower calorie intakes and underestimate at higher intakes [20].

- Key Challenge: Researchers identified transient signal loss from the sensor as a major source of error, highlighting the need for robust sensor fusion to compensate for such gaps.

The Feeding Table for High-Resolution Meal Microstructure

To address the limitations of single-food monitoring, researchers developed and validated the 'Feeding Table,' a novel Universal Eating Monitor (UEM) [31].

- Objective: To develop a UEM that simultaneously tracks the intake of up to 12 different foods with high temporal resolution, enabling detailed study of dietary microstructure and food choice.

- Participants: 31 healthy volunteers (15 male, 16 female) participated in a standard meal test over two consecutive days.

- Apparatus: The Feeding Table integrated five high-precision balances into a solid wood table, concealed beneath a hinged panel. Data from all balances were collected every 2 seconds and transmitted to a computer. The setup also included a video camera to record the eating process and identify which food was taken from each balance.

- Protocol: Participants consumed meals under standardized conditions. The table continuously recorded the weight of each food item throughout the meal.

- Validation Metrics: The study assessed day-to-day repeatability and positional bias. The Feeding Table showed high intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) for energy (0.94), protein (0.90), fat (0.90), and carbohydrate (0.93) across four repeated measurements, demonstrating excellent reliability. No significant positional bias was found for energy or macronutrients [31].

This protocol establishes the Feeding Table as a powerful tool for validating the output of less obtrusive wearable sensors in a laboratory setting, providing ground truth data for eating rate, meal size, and food choice.

iEat for Activity and Food Type Recognition

The iEat system represents a novel wearable approach that leverages an atypical use of bioimpedance sensing [30].

- Objective: To classify food intake-related activities and types of food using a wrist-worn impedance sensor.

- Principle: The system uses a two-electrode configuration (one on each wrist). During dining activities, dynamic circuit loops are formed through the hand, mouth, utensils, and food, causing consequential variations in the measured impedance signal. These patterns are unique to different activities and food types.

- Protocol: Ten volunteers performed 40 meals in an everyday table-dining environment. The iEat device collected impedance data during activities like cutting, drinking, eating with a hand, and eating with a fork.

- Data Processing and Model: A lightweight, user-independent neural network model was trained on the impedance signal patterns.

- Performance Outcome: The model detected the four food-intake activities with a macro F1 score of 86.4% and classified seven food types with a macro F1 score of 64.2% [30].

The following diagram illustrates the core sensing principle of the iEat device.

Diagram 1: iEat abstracted human-food impedance model. A new parallel circuit branch forms through food and utensils during dining activities, altering the overall impedance measured between the wrist-worn electrodes [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and technologies used in the featured experiments, providing a resource for researchers seeking to replicate or build upon these studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies for Dietary Monitoring

| Item / Technology | Function in Research | Exemplar Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Bioimpedance Sensor (2-electrode) | Measures electrical impedance across the body; signal variations indicate dynamic circuit changes during food interaction. | Core sensor in the iEat device for recognizing food-related activities and classifying food types [30]. |

| Multi-load Cell Weighing System | Provides high-precision, continuous measurement of food weight loss from multiple containers simultaneously. | The foundation of the Feeding Table (UEM) for monitoring eating microstructure and macronutrient intake [31]. |

| High-Fidelity Acoustic Sensor | Captures chewing and swallowing sounds, which have characteristic acoustic signatures for different foods and activities. | Used in neck-worn systems (e.g., AutoDietary) for solid and liquid food intake recognition [26]. |

| Wearable Camera | Passively captures images of food for subsequent analysis, providing visual context and data for food identification. | Validated for estimating food and nutrient intake in household settings in low- and middle-income countries [32]. |

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) | Measures interstitial glucose levels frequently; used to assess metabolic response and adherence to dietary protocols. | Referenced as a tool for measuring protocol adherence in the GoBe2 wristband validation study [20]. |

| Custom Data Fusion & ML Pipeline | Software framework for synchronizing multi-sensor data, extracting features, and running classification/regression models. | Critical for all studies employing feature-level or decision-level fusion to derive intake metrics from raw sensor data [28] [30]. |

The experimental workflow for validating a sensor fusion-based dietary monitoring system typically follows a structured path, as summarized below.

Diagram 2: Generalized workflow for validating a multi-sensor dietary monitoring system, highlighting the parallel paths of test data and reference data collection.

Accurate dietary assessment is fundamental to understanding the complex relationships between nutrition, chronic diseases, and health outcomes. Traditional methods, such as 24-hour recalls, food frequency questionnaires, and self-reported food records, are labor-intensive and suffer from significant limitations, including recall bias, misreporting, and the inherent subjectivity of participant input [33]. These methods place a substantial burden on participants, often leading to non-compliance and data that does not reflect habitual intake. In research settings, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where malnutrition remains a major public health concern, these challenges are even more pronounced [33].

The emergence of wearable devices for passive data capture offers a transformative approach to these long-standing methodological problems. As noted in a 2025 scoping review, "mobile and ubiquitous devices enable health data collection 'in a free-living environment'" with the potential to support remote patient monitoring and adaptive interventions while significantly reducing participant burden [34]. This guide objectively compares the current landscape of sensor-based and image-based technologies for validating food intake, focusing on their performance, underlying experimental protocols, and applicability for researchers and drug development professionals.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Research into passive dietary monitoring has converged on two primary technological approaches: sensor-based detection of eating behaviors and image-based capture of food consumption. The most robust systems often integrate both methodologies to enhance accuracy.

Sensor-Based Detection Systems

Sensor-based approaches typically leverage wearable devices equipped with accelerometers, gyroscopes, and other motion sensors to detect proxies of eating behavior such as chewing, swallowing, and hand-to-mouth gestures.

- AIM-2 Protocol: A key experimental system in this domain is the Automatic Ingestion Monitor v2 (AIM-2), a wearable device that attaches to eyeglasses and contains a camera and a 3D accelerometer [35]. In a validation study, 30 participants wore the AIM-2 for two days (one pseudo-free-living day with meals in the lab and one free-living day). The accelerometer sampled data at 128 Hz to capture head movement and body leaning forward motion as eating proxies. During the pseudo-free-living day, participants used a foot pedal to log the exact moment of food ingestion, providing precise ground truth data [35].

- Data Analysis: The sensor data was used to train a food intake detection model. The free-living day data, with eating episodes manually annotated from continuous images (captured every 15 seconds), served for validation [35].

Image-Based Assessment Systems

Image-based methods utilize wearable or fixed cameras to passively capture food consumption events, with subsequent analysis performed via manual review or automated computer vision techniques.

- Multi-Device Dietary Assessment: A comprehensive study protocol designed for LMIC settings (Ghana and Uganda) employs a suite of camera devices [33]:

- Foodcam: A stereoscopic camera mounted in kitchens with motion detection to capture food preparation.

- AIM-2: As described above, for gaze-aligned image capture during eating.

- eButton: A chest-worn device with a wide-angle, downward-tilted lens to record food in front of the wearer.

- Ear-worn camera: A lightweight, outwardly-directed camera for video capture of intake.

- Analytical Validation: This protocol validates the passive image-based method against the established ground truth of supervised weighed food records. The captured images are analyzed using both automated artificial intelligence (deep learning) and manual visual estimation to recognize foods and estimate portion size and nutrient content [33].

Integrated Multi-Modal Systems

The most significant advances in accuracy come from integrating sensor and image data. One study on the AIM-2 system implemented a hierarchical classifier to combine confidence scores from both image-based food recognition and accelerometer-based chewing detection [35]. This integrated method achieved a 94.59% sensitivity, 70.47% precision, and an 80.77% F1-score in free-living conditions, significantly outperforming either method used in isolation (8% higher sensitivity) by effectively reducing false positives [35].

Performance Comparison of Monitoring Technologies

The table below summarizes the key performance metrics of prominent wearable devices and sensing systems used for passive data capture in dietary and general health monitoring.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Passive Monitoring Technologies

| Device/System | Primary Data Type | Key Metrics/Performance | Reported Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| AIM-2 (Integrated Method) | Image & Accelerometer | 94.59% Sensitivity, 70.47% Precision (Eating Episode Detection) [35] | Significantly reduces false positives in free-living conditions. |

| Apple Watch | Physiological Sensors | ≤3.4% error (step count); 97% accuracy (sleep detection); Underestimates HR by 1.3 BPM (exercise) [36] | High consumer adoption; rich ecosystem for data integration. |

| Oura Ring | Physiological Sensors | 99.3% accuracy (resting HR); 96% accuracy (total sleep time) [36] | Unobtrusive form factor; strong sleep staging capability. |

| WHOOP | Physiological Sensors | 99.7% accuracy (HR); 99% accuracy (HRV) [36] | Focus on recovery and strain metrics; no screen minimizes distractions. |

| Garmin | Physiological Sensors | 1.16-1.39% error (HR); 98% accuracy (sleep detection) [36] | Robust activity and GPS tracking; popular in sport research. |

| Fitbit | Physiological Sensors | 9.1-21.9% error (step count); Overestimates total sleep time [36] | Widely used in research; established track record for basic activity. |

It is critical to note that while consumer-grade wearables provide valuable general health metrics, their accuracy for specific tasks like calculating caloric expenditure is considerably lower, with errors ranging from 13% (Oura Ring) to over 100% (Apple Watch) in some studies [36]. Therefore, their utility in dietary research may be more suited to contextual monitoring (e.g., correlating physical activity with appetite) rather than direct energy intake measurement.

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

The logical workflow for deploying and validating a passive food intake assessment system, particularly in challenging field conditions, can be summarized as follows.

Diagram 1: Passive Dietary Assessment Workflow.

The integrated analysis of image and sensor data for food intake detection follows a specific computational pipeline to reduce false positives.

Diagram 2: Integrated Image-Sensor Data Fusion.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Implementing a robust passive data capture study requires careful selection of devices and platforms. The table below details key components and their functions in a research context.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Passive Dietary Monitoring

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| AIM-2 (Automatic Ingestion Monitor v2) | Wearable Sensor | Captures gaze-aligned images and head movement accelerometer data for detecting eating episodes and identifying food [35]. |

| eButton | Wearable Sensor | A chest-worn device with a wide-angle view to passively capture images of food and activities in front of the wearer [33]. |

| Foodcam | Fixed Environmental Sensor | A stereoscopic kitchen camera with motion activation to capture images of food preparation and cooking processes [33]. |

| ExpiWell Platform | Data Integration Platform | Enables seamless synchronization of wearable data (e.g., from Apple Watch, Fitbit) with Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) data for a unified analysis dashboard [37]. |

| Hierarchical Classification Algorithm | Computational Method | A machine learning technique that combines confidence scores from image-based and sensor-based classifiers to improve the accuracy of eating episode detection and reduce false positives [35]. |

| Foot Pedal Logger | Ground Truth Apparatus | Provides precise, user-initiated ground truth data for food ingestion moments during laboratory validation studies [35]. |

Discussion and Research Considerations

While passive data capture technologies show immense promise, researchers must navigate several practical and methodological considerations. A 2025 review highlighted persistent challenges, including participant compliance in longer-term studies, data consistency from passive streams, and complex authorization and privacy issues, particularly when using cameras [34]. For special populations, such as persons with dementia (PwD), additional factors like device comfort, ease of use, and reliance on caregivers become critical for successful adoption and adherence [38].

Machine learning techniques offer promising solutions to some of these challenges by optimizing the timing of prompts for active data collection, auto-filling responses, and minimizing the frequency of interruptions to the participant [34]. Simplified user interfaces and motivational techniques can further improve compliance and data consistency [34].

When selecting devices, researchers should employ a structured evaluation framework that considers criteria across three domains: Everyday Use (e.g., battery life, comfort, aesthetics), Functionality (e.g., parameters measured, connectivity), and Research Infrastructure (e.g., data granularity, export capabilities) [39]. No single device is best for all scenarios; selection must be driven by the specific research question, target population, and study context.

The objective assessment of dietary intake represents a significant challenge in nutritional science and chronic disease management. Traditional methods, such as food diaries and 24-hour dietary recalls, are prone to inaccuracies due to their reliance on self-reporting, which can be influenced by recall bias and the burden of manual entry [40]. For individuals with Type 2 Diabetes (T2D), this gap in accurate monitoring can hinder effective glycemic control. The integration of two wearable technologies—Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGM) and the eButton, a wearable dietary intake sensor—offers a promising, multi-modal approach to objectively capture the relationship between food consumption and physiological response. This case study frames the integration of CGM and eButton within a broader research thesis aimed at validating food intake data through wearable devices, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a critical evaluation of the performance, protocols, and potential of this combined methodology.

Performance Comparison of Current-Generation CGM Systems

The selection of an appropriate CGM is foundational to any study correlating dietary intake with glycemic response. A recent 2025 prospective, interventional study provides a robust, head-to-head comparison of three factory-calibrated CGM systems, evaluating their performance against different comparator methods (YSI 2300 laboratory analyzer, Cobas Integra analyzer, and Contour Next capillary blood glucose meter) and during clinically relevant glycemic excursions [41].

Table 1: CGM System Performance Metrics (vs. YSI Reference)

| CGM System | Mean Absolute Relative Difference (MARD) | Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| FreeStyle Libre 3 (FL3) | 11.6% | Better accuracy in normoglycemic and hyperglycemic ranges. |

| Dexcom G7 (DG7) | 12.0% | Better accuracy in normoglycemic and hyperglycemic ranges. |

| Medtronic Simplera (MSP) | 11.6% | Better performance in the hypoglycemic range. |

Table 2: CGM System Technical Specifications

| Feature | FreeStyle Libre 3 | Dexcom G7 | Medtronic Simplera |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensor Lifetime | 14 days [41] | 10 days + 12-hour grace period [41] [42] | 7 days [41] |

| Warm-Up Time | Not specified in search results | 30 minutes [42] | Not specified in search results |

| Reader | Smartphone app [43] | Smartphone app or redesigned receiver [42] | Not specified in search results |

| Key Integrations | mylife CamAPS FX AID system, YpsoPump, Tandem t:slim X2, Beta Bionics iLet, twiist AID System* [43] [44] | Tidepool Loop [42]; other AID integrations in development [42] | Not specified in search results |

*Integration specified for FreeStyle Libre 3 Plus or FreeStyle Libre 2 Plus sensors [43] [44].

It is critical to note that performance results varied depending on the comparator method. For instance, compared to the Cobas Integra (INT) method, the MARD for FL3, DG7, and MSP was 9.5%, 9.9%, and 13.9%, respectively [41]. This underscores the importance of the reference method in study design and the interpretation of performance data. All systems demonstrated a lower aggregate accuracy compared to some previous studies, highlighting the effect of comprehensive study designs that include dynamic glucose regions [41].

The eButton: A Wearable Sensor for Dietary Monitoring