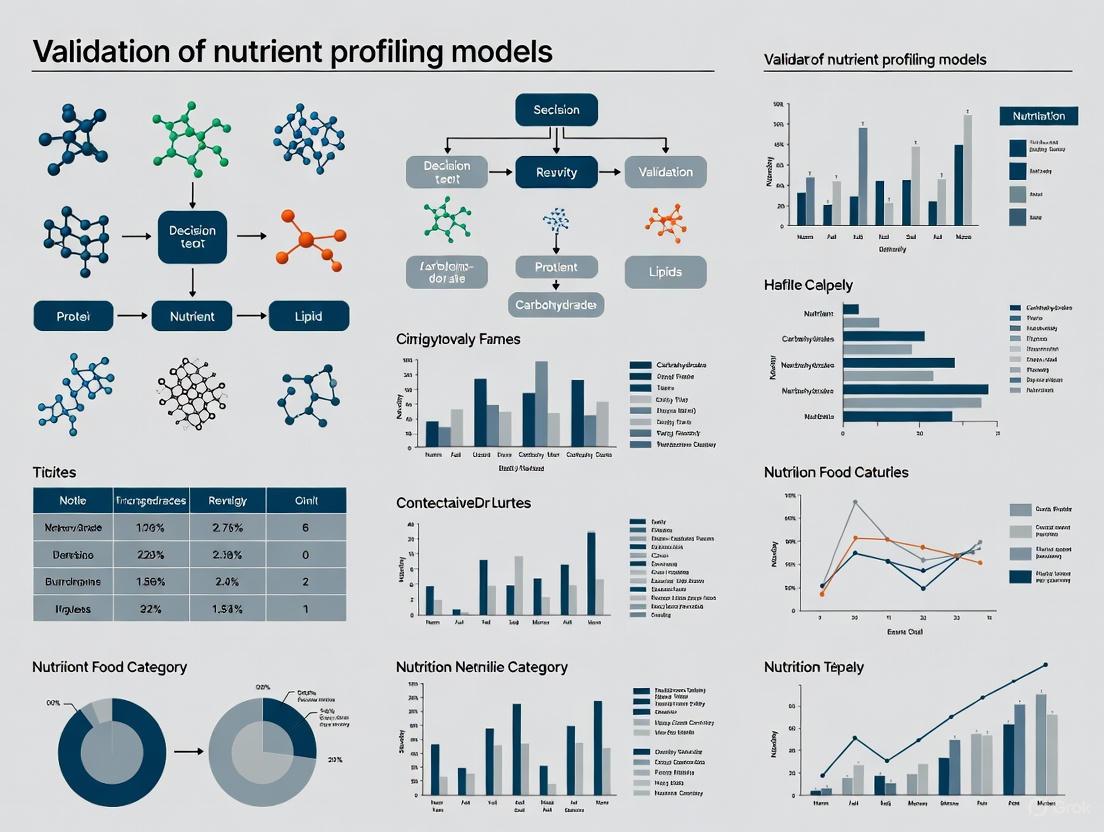

Validation of Nutrient Profiling Models: A Scientific Framework for Assessing Nutritional Quality Across Food Categories

This article provides a comprehensive scientific review of methodologies for validating nutrient profiling (NP) models, which are critical tools for classifying foods based on their nutritional composition.

Validation of Nutrient Profiling Models: A Scientific Framework for Assessing Nutritional Quality Across Food Categories

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive scientific review of methodologies for validating nutrient profiling (NP) models, which are critical tools for classifying foods based on their nutritional composition. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of content and construct validity, details the application of various NP models across different food categories and regional contexts, addresses key challenges in model implementation and optimization, and synthesizes the current state of criterion validation evidence linking NP models to health outcomes. The review underscores the importance of robust validation for ensuring these models effectively support public health initiatives, clinical nutrition, and the development of functional foods and nutraceuticals.

The Science of Classification: Foundational Principles of Nutrient Profiling Models

Nutrient profiling (NP) is defined as the science of classifying or ranking foods according to their nutritional composition for reasons related to preventing disease and promoting health [1]. This methodological approach provides quantitative algorithms that evaluate and rank the healthfulness of foods and beverages based on their nutrient content, translating complex nutritional information into actionable data [2] [3]. As a foundational tool in nutritional science, nutrient profiling serves as a critical bridge between dietary guidance and food product assessment, enabling evidence-based decision-making across multiple sectors.

The primary objective of nutrient profiling systems (NPSs) is to characterize the overall nutritional quality of individual food items in a standardized, objective, and reproducible manner [4] [1]. This characterization typically results in either numerical scores or classification categories that reflect a food's contribution to a healthy diet. By creating standardized evaluation frameworks, NP models allow for direct comparisons between diverse food products, informing both individual consumer choices and population-level health policies.

Key Objectives in Public Health and Clinical Research

Public Health Applications

Nutrient profiling systems serve as the scientific foundation for numerous public health initiatives aimed at improving dietary patterns at the population level. These applications include:

Front-of-pack (FOP) labeling: Providing simplified nutritional guidance to help consumers make healthier food choices during purchase decisions [4] [1]. NP models underpin various FOP labeling schemes worldwide, including the Nutri-Score and Health Star Rating systems, which transform complex nutritional information into easily interpretable visual cues [3] [4].

Regulation of food marketing to children: Restricting the promotion of foods high in saturated fats, trans fats, free sugars, or salt to children, a strategy recommended by the World Health Organization to combat childhood obesity [4] [5]. The WHO has developed specific nutrient profiling models to identify food products that should not be marketed to children, helping to create healthier food environments for vulnerable populations [5].

Food taxation and subsidies: Informing fiscal policies that discourage consumption of less healthy foods or encourage consumption of more nutritious options [1]. By establishing objective criteria for categorizing foods, NP models provide the evidence base for economic interventions designed to shift consumption patterns toward healthier options.

Nutrition and health claims regulation: Determining which food products qualify to carry specific nutrient content or health claims on packaging [1]. This application ensures that marketing claims are scientifically valid and not misleading to consumers, maintaining the integrity of food labeling.

Food procurement standards: Setting nutritional standards for foods served in public institutions such as schools, hospitals, and government facilities [4] [1]. These standards help ensure that public institutions provide healthy food options, particularly important for vulnerable populations who may rely on these services for a significant portion of their nutritional intake.

Clinical and Research Applications

In clinical and research contexts, nutrient profiling enables:

Nutritional surveillance: Tracking changes in the nutritional quality of the food supply over time and across different regions [1]. This monitoring function helps researchers and policymakers assess the effectiveness of interventions and identify emerging challenges in food composition.

Epidemiological research: Investigating associations between consumption of differently profiled foods and health outcomes in population studies [2] [3]. Researchers can use NP scores to categorize dietary patterns and examine their relationship with disease incidence, progression, and mortality.

Product reformulation: Guiding food manufacturers in improving the nutritional quality of existing products and developing new, healthier options [6] [5]. Progressive NP systems, such as the PepsiCo Nutrition Criteria, provide stepwise targets that allow for incremental improvements in product formulation, making healthier products technically feasible and commercially viable [6].

Personalized nutrition: Informing dietary recommendations tailored to individual health status, genetic predispositions, and metabolic responses [7]. Emerging dynamic nutrient profiling systems incorporate real-time data to provide adaptive nutritional guidance that accounts for individual variability in nutrient requirements and responses.

The following table summarizes the primary objectives and applications of nutrient profiling across different sectors:

Table 1: Key Objectives and Applications of Nutrient Profiling

| Sector | Primary Objectives | Specific Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Public Health | Improve population dietary patterns; Reduce diet-related non-communicable diseases | Front-of-pack labeling; Marketing restrictions; Food taxation/subsidies; Public institution food standards |

| Clinical Research | Understand diet-disease relationships; Develop dietary interventions | Nutritional epidemiology; Clinical trials; Dietary assessment methods |

| Food Industry | Improve product nutritional quality; Support product development | Product reformulation; Innovation benchmarking; Portfolio analysis |

| Regulatory Affairs | Ensure accurate food labeling; Protect vulnerable populations | Health claim regulation; Marketing controls; School food standards |

Comparative Analysis of Major Nutrient Profiling Systems

Various nutrient profiling systems have been developed globally, each with distinct algorithms, nutrient considerations, and validation approaches. The following section provides a detailed comparison of prominent models, their methodologies, and applications.

System Classifications and Algorithmic Structures

Nutrient profiling systems generally fall into several categorical approaches:

Threshold-based systems: Establish specific cut-off points for nutrients, where foods must meet all criteria to qualify for a particular classification [6]. The PepsiCo Nutrition Criteria employs this approach with four progressive classes (I-IV) of increasing nutritional quality [6].

Scoring systems: Assign points based on nutrient content, generating continuous or categorical scores that reflect overall nutritional quality [2] [3]. The Food Compass system uses a 100-point scale based on multiple domains of product characteristics [2].

Nutrient-rich food indices: Calculate scores based on the ratio of beneficial nutrients to limiting nutrients [5]. The Nutrient-Rich Foods Index (NRF) family of models uses this approach, subtracting the sum of percentage daily values for limiting nutrients from the sum of percentage daily values for beneficial nutrients [5].

The following table compares the algorithmic structures of major nutrient profiling systems:

Table 2: Algorithmic Comparison of Major Nutrient Profiling Systems

| System Name | Algorithm Type | Nutrients to Encourage | Nutrients to Limit | Output Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Compass 2.0 | Multidomain scoring | Fiber, protein, vitamins, minerals, specific food ingredients | Added sugars, sodium, saturated fat, processing indicators | 1-100 points |

| Nutri-Score | Threshold-based scoring | Protein, fiber, fruits/vegetables/nuts | Energy, sugars, saturated fat, sodium | A-E (5-color scale) |

| Health Star Rating (HSR) | Modified threshold-based | Protein, fiber, fruits/vegetables/nuts/legumes | Energy, sugars, saturated fat, sodium | 0.5-5 stars |

| Meiji NPS | Nutrient density index | Protein, dietary fiber, calcium, iron, vitamin D | Energy, saturated fatty acids, sugar, salt equivalents | Continuous score |

| SENS | Dual-component scoring | Protein, fiber, vitamins, minerals | Saturated fat, added sugars, sodium | 4 classes |

Validation Methodologies and Performance Metrics

Validation represents a critical step in establishing the scientific credibility and practical utility of nutrient profiling systems. Multiple validation approaches have been employed:

Criterion validation: Assesses the relationship between consuming foods rated as healthier by the NPS and objective measures of health [3]. This gold-standard approach examines whether the profiling system predicts health outcomes in prospective cohort studies.

Dietary pattern validation: Tests whether the NP system appropriately ranks foods in relation to the overall nutritional quality of diets [8]. This method compares food classifications against validated measures of diet quality such as the Healthy Eating Index.

Convergent validation: Examines the agreement between different profiling systems when applied to the same set of foods [2] [9]. While different systems show general concordance for extreme foods (very healthy or very unhealthy), significant discrepancies often emerge for intermediate products [9].

A 2022 systematic review of criterion validation studies found substantial evidence for the Nutri-Score system, with highest compared to lowest diet quality associated with significantly lower risk of cardiovascular disease (HR: 0.74), cancer (HR: 0.75), and all-cause mortality (HR: 0.74) [3]. The Food Standards Agency NPS, Health Star Rating, and Food Compass were determined to have intermediate criterion validation evidence [3].

The updated Food Compass 2.0 demonstrated strong predictive validity in US adults, with each standard deviation higher score associated with favorable health outcomes including lower BMI (-0.56 kg/m²), systolic blood pressure (-0.55 mm Hg), LDL cholesterol (-1.49 mg/dL), and prevalence of metabolic syndrome (OR: 0.86) [2].

Comparative Performance Across Food Categories

Different nutrient profiling systems demonstrate varying performance across food categories, reflecting their distinct algorithmic structures and nutrient priorities:

Table 3: Food Category Performance Comparison Across Profiling Systems

| Food Category | Food Compass 2.0 | Nutri-Score | Health Star Rating | SENS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruits & Vegetables | High (53-63% score ≥70) | Generally favorable | Generally favorable | Class 1 predominance |

| Seafood | Very high (82% score ≥70) | Variable by preparation | Variable by preparation | Class 1-2 predominance |

| Nuts & Legumes | High (80-89% score ≥70) | Generally favorable | Generally favorable | Class 1-2 predominance |

| Meat, Poultry, Eggs | Moderate (52-89% score 31-69) | Variable by fat content | Variable by fat content | Class 2-3 predominance |

| Processed Cereals | Low to moderate | Generally less favorable | Generally less favorable | Class 3-4 predominance |

| Sugar-sweetened Beverages | Very low (54% score ≤30) | Least favorable (D/E) | Least favorable (0.5-2 stars) | Class 4 predominance |

Recent comparative analyses reveal that while different systems generally agree on extreme foods (e.g., fruits and vegetables as healthy, sugary beverages as unhealthy), they show significant discrepancies for processed foods, dairy products, and certain protein sources [2] [9]. For example, Food Compass 2.0 provides higher scores for minimally processed animal foods including seafood, dairy, meat, poultry, and eggs compared to its previous version, while assigning lower scores to processed cereals, beverages, and processed plant-based alternatives [2].

Experimental Protocols for Validation Studies

Criterion Validation Protocol

Criterion validation represents the most rigorous approach to establishing the predictive validity of nutrient profiling systems. The following protocol outlines the standard methodology:

Population Recruitment and Assessment:

- Recruit a representative cohort of adults (typically n > 10,000) from national health surveys

- Collect comprehensive dietary intake data using validated food frequency questionnaires or 24-hour recalls

- Measure clinical health parameters including BMI, blood pressure, lipid profiles, and glycemic markers

- Document prevalent health conditions and incident disease cases through medical records and follow-up

Dietary Pattern Analysis:

- Calculate individual NP scores by computing the energy-weighted average of all foods consumed

- Classify participants into quintiles or categories based on their overall dietary NP score

- Use multivariable regression models to assess associations between NP scores and health outcomes

- Adjust for potential confounders including age, sex, physical activity, smoking status, and total energy intake

Statistical Analysis:

- Calculate hazard ratios (HR) or odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals for disease outcomes

- Perform trend tests across NP score categories

- Assess discrimination using C-statistics or similar metrics

- Conduct sensitivity analyses to test robustness of findings

A recent systematic review applying this protocol found that the Nutri-Score system demonstrated significant criterion validity, with highest compared to lowest diet quality associated with a 26% lower risk of cardiovascular disease, 25% lower cancer risk, and 26% lower all-cause mortality risk [3].

Diet Optimization Validation Protocol

The diet optimization approach tests whether NP systems align with theoretical healthy diets designed to meet nutritional requirements:

Linear Programming Methodology:

- For each individual observed diet in a sample population, design an iso-caloric optimized diet that meets all nutrient recommendations

- Use linear programming with decision variables representing food amounts

- Define constraints based on WHO and national nutrient recommendations

- Minimize the objective function representing dietary changes from observed to optimized patterns

Frequency Analysis:

- Calculate daily consumption frequencies (portions/day) for each NP class in both observed and optimized diets

- Compare the distribution of NP classes between observed and optimized diets

- Test the hypothesis that optimization increases Class 1 foods and decreases Class 4 foods

- Calculate percentage of individuals showing increased consumption of favorable NP classes after optimization

Validation Metrics:

- Statistical comparison of NP class frequencies between observed and optimized diets using generalized linear models

- Assessment of linear trends across NP classes

- Percentage of individuals with increased favorable NP class consumption after optimization

Application of this protocol to the SENS system demonstrated that in optimized diets, daily frequency increased for Class 1 foods for 98.4% of individuals and decreased for Class 4 foods for 94.2% of individuals, validating the system's alignment with nutritional recommendations [8].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Methodologies

Essential Research Databases and Tools

Table 4: Essential Research Resources for Nutrient Profiling Studies

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Food Composition Databases | CIQUAL (France), USDA FoodData Central, Japanese Food Standard Composition Table | Provide standardized nutrient composition data for scoring individual foods |

| Dietary Assessment Tools | 24-hour recalls, Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQ), diet records | Capture individual food consumption patterns for validation studies |

| Statistical Software | R, SAS, SPSS, STATA | Perform complex statistical analyses including linear programming and multivariate modeling |

| Health Outcome Databases | National health surveys, disease registries, cohort studies | Provide criterion variables for validation against health endpoints |

| Nutrient Profiling Algorithms | Food Compass, Nutri-Score, HSR, NRF, SENS | Standardized methods for calculating food healthfulness scores |

Methodological Standards and Protocols

Linear Programming Optimization: Mathematical approach for designing theoretically optimal diets that meet nutritional constraints while minimizing dietary changes [8]. This method tests whether NP classifications align with nutritionally ideal dietary patterns.

Multi-variable Adjustment Models: Statistical protocols for controlling confounding factors when examining relationships between NP scores and health outcomes [2] [3]. Standard adjustments include age, sex, BMI, physical activity, smoking status, and total energy intake.

Portion Size Standardization: Methods for converting food consumption data into standardized portions to enable frequency analysis across different food categories [8]. This standardization is essential for comparing consumption patterns across NP classes.

Energy Density Calculations: Protocols for calculating the energy content per unit weight of foods, an important metric in dietary quality assessment [8]. Energy density often correlates with NP classifications and provides complementary information about food quality.

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of nutrient profiling continues to evolve with several emerging trends shaping future research and applications:

Dynamic Nutrient Profiling: The next generation of NP systems incorporates real-time nutritional assessment with individualized dietary recommendations through advanced algorithmic approaches, biomarker integration, and artificial intelligence [7]. These systems account for temporal variability in nutritional needs throughout different life stages and physiological states.

Multi-omics Integration: Emerging profiling systems incorporate genetic, metabolomic, and microbiome data to personalize nutritional recommendations based on individual metabolic responses [7]. This approach recognizes the substantial inter-individual differences in nutrient requirements and metabolic responses that influence optimal dietary patterns.

Life-stage Specific Models: Development of age-sensitive profiling systems that address specific nutritional priorities at different life stages, as demonstrated by the Meiji NPS for children, adults, and older adults [5]. These models account for varying nutrient requirements and health priorities across the lifespan.

Enhanced Processing Considerations: Modern NP systems increasingly incorporate food processing characteristics beyond traditional nutrient-based criteria [2]. Food Compass 2.0, for example, provides positive points for non-ultraprocessed foods rather than only penalizing ultraprocessed products.

Geographic and Cultural Adaptation: Growing recognition of the need to adapt NP systems to regional dietary patterns, food traditions, and public health priorities [4] [5]. This trend acknowledges that optimal NP systems must be culturally relevant to effectively guide food choices.

As the field advances, key research priorities include methodological standardization, long-term validation studies, comprehensive cost-effectiveness analyses, and addressing equity concerns in vulnerable populations [7]. The integration of artificial intelligence and multi-omics data represents the future direction of this rapidly evolving field, promising more personalized and effective nutritional guidance.

Nutrient profiling (NP) is defined as the science of classifying or ranking foods based on their nutritional composition for purposes of health promotion and disease prevention [10] [11] [12]. Initially developed in the 1980s, NP models have proliferated significantly, with one systematic review identifying 387 distinct models by 2016 [10]. These models provide transparent, reproducible methods for evaluating the healthfulness of foods and serve as critical tools for numerous applications, including front-of-pack labeling, food taxation, marketing restrictions, product reformulation, and guiding consumer choices [10] [11] [13]. The fundamental principle underlying all NP models is the systematic assessment of a food's nutritional composition, typically by evaluating components that should be limited in the diet and those that should be encouraged.

The conceptual framework of NP model development follows a structured pathway from identifying public health needs to creating a functional policy tool. The process begins with defining the model's purpose and target population, then selects appropriate nutrients and food components to include, determines the model type and base (e.g., per 100g or per serving), and finally establishes scoring thresholds [13]. This structured approach ensures the resulting model is fit-for-purpose, whether for consumer education, regulatory policies, or industry self-regulation. As NP models have evolved, a key challenge has been balancing scientific rigor with practical implementation, leading to ongoing refinements in how models define and weight their core components [14] [6].

Core Components of NP Models

Nutrients to Limit

Nutrients to limit, often termed "negative" nutrients, form a consistent foundation across nearly all NP models. These components are typically associated with adverse health outcomes when consumed in excess and include energy (calories), saturated fats, sodium, and total or free sugars [10] [6] [13]. Some models also address trans fats, whether industrially produced or total trans fats, recognizing their particularly detrimental health effects [10]. The inclusion of these nutrients reflects global public health priorities aimed at addressing obesity and non-communicable diseases by reducing consumption of energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods [6] [13].

The specific nutrients selected for limitation vary somewhat between models, reflecting different public health priorities and regional dietary concerns. For instance, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) model includes industrially produced trans fats as a component to limit [10], while the Ofcom model, originally developed for regulating television advertising to children in the United Kingdom, focuses on energy, saturated fat, total sugar, and sodium [10] [15]. More recent models have begun distinguishing between total sugars and free sugars (those added to foods plus naturally occurring sugars in honey, syrups, and fruit juices), acknowledging differing health implications, though evidence suggests this substitution may have minimal impact on model performance [16].

Nutrients and Components to Encourage

Nutrients and food components to encourage represent the "positive" elements in NP models, highlighting beneficial nutrients often lacking in modern diets. These typically include protein, dietary fiber, and specific vitamins and minerals identified as nutrients of public health concern [10] [14] [6]. Additionally, many models incorporate the presence of specific food groups to encourage, such as fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, legumes, whole grains, and in some cases, low-fat dairy products [10] [6]. The inclusion of these components helps distinguish between merely "less bad" foods and genuinely nutrient-dense options.

The selection of encouraged components varies significantly based on model purpose and regional nutritional priorities. For example, the Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) model includes fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes as components to encourage [10], while the Nestlé Nutritional Profiling System emphasizes vitamins and minerals with documented inadequacies in target populations [6]. For low- and middle-income countries, NP models may prioritize different nutrients, focusing on inadequate intakes of vitamin A, B vitamins, folate, calcium, iron, iodine, zinc, and high-quality protein to address persistent micronutrient deficiencies [14]. This adaptation highlights how NP models must reflect regional nutritional challenges to be effective.

Table 1: Core Components in Major Nutrient Profiling Models

| NP Model | Nutrients to Limit | Nutrients/Components to Encourage | Reference Amount |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ofcom (UK) | Energy, saturated fat, total sugar, sodium | Protein, fiber, fruit, vegetable & nut content | 100g |

| FSANZ (Australia/NZ) | Energy, saturated fat, total sugar, sodium | Protein, fiber, fruit, vegetable & nut content | 100g or ml |

| Nutri-Score (France) | Energy, saturated fat, total sugar, sodium | Protein, fiber, fruit, vegetable & nut content | 100g |

| HCST (Canada) | Sodium, saturated fat, sugar, specific thresholds for "other nutrients" | Tier-based system aligned with national food guide | Serving |

| PAHO (Americas) | Saturated fat, trans fat, sodium, free sugar | Not specified in available data | % energy of food |

| EURO (Europe) | Saturated fat, sodium, total sugar, sweeteners, energy in drinks | Protein, fiber, fruit, vegetable & nut content | 100g |

| PepsiCo PNC | Added sugars, saturated fat, sodium, industrially-produced trans fats | Food groups to encourage (fruits, vegetables, whole grains, etc.), country-specific gap nutrients | Varies by category |

Structural Variations Across Models

NP models diverge significantly in their structural approaches, including differences in reference amounts (e.g., per 100g, per serving, or percentage of energy), scoring systems (continuous, categorical, or dichotomous), and food categorization schemes [10] [6]. These structural decisions profoundly impact how models classify foods and their suitability for different applications. The reference amount is particularly influential, with most international models using 100g for comparability, while some region-specific models like Canada's HCST use serving sizes, which may better reflect consumption patterns but complicate cross-product comparisons [10].

Food categorization strategies represent another key structural variation. Some models employ a across-the-board approach with uniform criteria for all foods, while others use category-specific thresholds that account for the different roles foods play in the diet and their inherent nutritional limitations [6] [15]. For instance, the PepsiCo Nutrition Criteria (PNC) system divides foods into 20 distinct categories with tailored criteria for each, acknowledging that a single set of thresholds cannot fairly evaluate nutritionally diverse food groups [6]. Similarly, the 5-Colour Nutrition Label (5-CNL) in France required adaptations for specific food categories like beverages, added fats, and cheeses to maintain consistency with national nutritional recommendations [15].

Table 2: Model Structures and Applications

| NP Model | Model Structure | Food Categories | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ofcom | Continuous score (0-40) converted to quartiles | 2 broad categories | Marketing restrictions to children |

| Nutri-Score | Continuous score converted to 5-color/letter classes | 2 broad categories | Front-of-pack labeling |

| HCST | 4-tier system | 4 categories | Surveillance, dietary guidance |

| PepsiCo PNC | 4-class progressive system | 20 defined categories | Product reformulation & innovation |

| SA NPM | Dichotomous (pass/fail) | Category-specific | Multiple restrictive policies |

| WHO EURO | Dichotomous thresholds | 18 food categories | Marketing restrictions |

Experimental Validation of NP Models

Validation Methodologies

Validating NP models requires rigorous methodologies to assess their reliability and real-world applicability. The 2018 study by Braesco et al. provides a comprehensive example of validation protocols, examining both content validity and construct/convergent validity of five NP models from different regions [10]. Content validity was assessed by evaluating how well each model's algorithmic underpinnings aligned with current scientific literature, particularly regarding inclusion of recognized nutrients of public health concern [10]. This involved systematic comparison of the nutrients and components considered by each model against established nutritional priorities.

Construct/convergent validity was tested by comparing each model's classifications against the previously validated Ofcom model as a reference standard [10]. Using data from the 2013 University of Toronto Food Label Information Program (n=15,342 foods/beverages), researchers employed multiple statistical analyses: Cochran-Armitage trend tests to assess associations between model classifications, kappa statistics to measure agreement beyond chance, and McNemar's tests to identify discordant classifications [10]. This multi-faceted approach provided a robust assessment of how different models perform relative to an established benchmark across diverse food categories. Additional validation approaches include testing associations between NP model scores and diet quality measures or health biomarkers, as demonstrated in the PREDISE study, which examined relationships between NP scores and body mass index, blood pressure, triglycerides, and other cardiometabolic risk factors [16].

Comparative Performance Across Models

Validation studies reveal significant variation in how different NP models perform when applied to real-world food supplies. The 2018 comparative study found "near perfect" agreement with the Ofcom reference standard for FSANZ (κ=0.89) and Nutri-Score (κ=0.83) models, "moderate" agreement for the EURO model (κ=0.54), and only "fair" agreement for PAHO (κ=0.28) and HCST (κ=0.26) models [10]. The percentage of foods with discordant classifications varied similarly, ranging from just 5.3% for FSANZ to 37.0% for HCST [10]. These substantial differences highlight how structural decisions and component selection dramatically impact model outcomes.

Application studies further demonstrate how NP models perform in specific contexts. A 2025 analysis of child-targeted foods in Türkiye found that 93.2% of products did not comply with WHO NPM-2023 criteria and should not be marketed to children, with the majority classified as Nutri-Score D and E (70%) and as ultra-processed (92.7%) [11] [12]. This convergence between different validation approaches - model-to-model comparison and real-world application - strengthens confidence in the performance of certain models like Nutri-Score and WHO NPM for regulatory purposes, while suggesting needed refinements for others.

NP Model Development and Validation Workflow

Research Toolkit for NP Model Development and Validation

Essential Databases and Analytical Tools

Researchers developing and validating NP models require access to comprehensive food composition databases and specialized analytical tools. The USDA Branded Food Products Database (BFPDB) provides detailed nutritional information for commercial food products, enabling robust analysis of how NP models perform across diverse food categories [14]. Similarly, national food composition databases like the Turkish National Food Composition Database (TURKOMP) and collaborative projects like Open Food Facts offer region-specific data critical for adapting international models to local contexts [11] [15]. These databases provide the foundational data upon which NP models are built and validated.

Statistical software packages (e.g., R, SAS, SPSS) equipped with specialized analytical capabilities are essential for model validation. Researchers must implement statistical tests including Cochran-Armitage trend tests to assess associations between model classifications, kappa statistics to measure inter-model agreement beyond chance, and McNemar's tests to identify discordant classifications [10]. For studies examining associations with health outcomes, multivariate linear models that adjust for potential confounding variables (age, sex, energy intake) are necessary to isolate the relationship between NP model scores and biomarkers of health status [16].

Methodological Protocols for Key Experiments

Table 3: Experimental Protocols for NP Model Validation

| Experiment Type | Core Methodology | Key Metrics | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Comparison Study | Apply multiple NP models to identical food database (n=15,342+ foods); Statistical comparison against reference standard | Trend tests (Cochran-Armitage), Agreement (kappa statistic), Discordance (McNemar's test) | Comparison of 5 NP models against Ofcom benchmark [10] |

| Biomarker Association Study | Collect dietary intake data (e.g., 24-h recalls); Calculate energy-weighted NP scores; Assess associations with health biomarkers | Multivariable linear models; Adjusted R²; Beta coefficients for BMI, blood pressure, lipids, HOMA-IR | PREDISE study examining HSR, Nutri-Score, NRF models [16] |

| Real-World Compliance Assessment | Systematic sampling of targeted products (e.g., child-marketed foods); Apply NP models and processing classification (NOVA) | Percentage non-compliant with NP models; Distribution across model categories; Processing level distribution | Evaluation of child-targeted foods in Türkiye using WHO NPM, Nutri-Score [11] [12] |

| Model Adaptation Protocol | Identify discrepancies between model output and national recommendations; Modify scoring components while maintaining structure; Retest performance | Distribution across food groups; Discriminatory performance within categories; Consistency with national guidelines | Adaptation of FSA score for French 5-CNL label [15] |

Nutrient profiling models share a common foundation in evaluating nutrients to limit and encourage, but differ significantly in their specific components, structural approaches, and performance characteristics. The core components to limit consistently include saturated fat, sodium, and sugars, while components to encourage typically encompass protein, fiber, and specific beneficial food groups. Validation studies demonstrate that models like FSANZ and Nutri-Score show strong agreement with reference standards, while others may require refinement for optimal performance.

The ongoing evolution of NP models reflects advancing nutritional science and diverse policy applications. Future developments will likely include refined distinctions between sugar types, enhanced consideration of food processing levels, and improved adaptation to regional nutritional priorities. As NP models continue to underpin critical nutrition policies, understanding their core components, validation methodologies, and performance characteristics remains essential for researchers, policymakers, and industry professionals working at the intersection of nutrition science and public health.

Nutrient profiling (NP) models are the science of classifying foods based on their nutritional composition to promote health and prevent disease [10]. As these models form the basis for critical public health policies—from front-of-pack (FOP) labeling to marketing restrictions and food reformulation—establishing their content validity is paramount [10]. Content validity assesses the extent to which a model's components (e.g., the nutrients and food groups it includes) comprehensively and appropriately reflect the construct it aims to measure, which in this case is the "healthfulness" of a food as defined by national and international dietary guidelines [10] [17].

This guide provides an objective comparison of how major NP models align with dietary guidelines, serving as a practical resource for researchers, regulatory agencies, and product developers engaged in model selection, validation, and application.

Comparative Analysis of NP Model Components and Dietary Alignment

The content validity of an NP model is primarily determined by its selection of nutrients to encourage and limit, which should directly reflect nutrients of public health concern identified by authoritative dietary guidance.

Table 1: Core Components of Prominent Nutrient Profiling Models

| NP Model | Key Nutrients to Encourage | Key Nutrients to Limit | Basis in Dietary Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutri-Score [10] [18] | Protein, Fiber, Fruits/Vegumes/Nuts (FVNL) | Energy, Saturated Fat, Total Sugars, Sodium | European dietary guidance; focuses on reducing non-communicable diseases (NCDs). |

| Health Star Rating (HSR) [18] | Protein, Fiber, Fruits, Vegetables, Nuts, Legumes | Energy, Saturated Fat, Total Sugars, Sodium | Australia/New Zealand Dietary Guidelines; category-specific adjustments. |

| Balanced Hybrid NDS (bHNDS) [18] | Protein, Fiber, Calcium, Iron, Potassium, Vitamin D; Food Groups (Whole Grains, Nuts, Dairy, Vegetables, Fruit) | Saturated Fat, Added Sugar, Sodium | Aligns with US Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA), addressing nutrients of public health concern. |

| WHO WPRO Model [5] | (Varies by application; often category-specific micronutrients) | Energy, Saturated Fats, Total/Added Sugar, Sodium, Non-Sugar Sweeteners | WHO global and regional recommendations; used to restrict marketing to children. |

| Meiji NPS (Children) [5] | Protein, Dietary Fiber, Calcium, Iron, Vitamin D; Food Groups (Dairy, Fruits, Vegetables, Nuts, Legumes) | Energy, Saturated Fatty Acids, Sugars, Salt Equivalents | Japanese Dietary Reference Intakes; addresses growth and development needs. |

| PAHO & HCST Models [10] [19] | (Varies; PAHO focuses on limits) | Free Sugars, Sodium, Saturated Fat, Trans-Fat | PAHO aligns with regional priorities for the Americas; HCST is used for surveillance in Canada. |

Table 2: Quantitative Validation Metrics of NP Models Against Reference Standards

| NP Model | Reference Standard | Key Validation Metric | Result | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSANZ [10] | Ofcom | Agreement (κ statistic) | κ = 0.89 | "Near perfect" agreement |

| Nutri-Score [10] | Ofcom | Agreement (κ statistic) | κ = 0.83 | "Near perfect" agreement |

| bHNDS (Diet-level) [18] | HEI-2015 | Pearson Correlation (r) | r = 0.67, p < 0.001 | Strong, significant correlation with a validated diet quality index. |

| bHNDS (Food-level) [18] | Nutri-Score | Pearson Correlation (r) | r = 0.60, p < 0.001 | Significant correlation with another FOP model. |

| Meiji NPS [5] | NRF9.3 | Pearson Correlation (r) | r = 0.73 | Strong correlation with a validated nutrient-density index. |

| Grocery Basket Score (GBS) [20] | AHEI | Pearson Correlation (r) | r = 0.62 | High degree of correlation with a mortality-risk-predictive diet index. |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Content Validity

A robust assessment of content validity involves multiple experimental approaches, ranging from alignment checks with dietary recommendations to statistical validation against independent measures of a healthy diet.

Methodology for Component Alignment Analysis

This protocol evaluates how well an NP model's architecture reflects current dietary guidelines [10] [17].

- Step 1: Identify Reference Guidelines: Define the national or international dietary guidelines used as the benchmark (e.g., Dietary Guidelines for Americans, WHO recommendations) [21] [22].

- Step 2: Extract Key Dietary Components: Systematically extract from the guidelines a list of:

- Nutrients of Public Health Concern: Both shortfall nutrients (e.g., fiber, calcium, potassium, vitamin D, iron) and overconsumed nutrients (e.g., saturated fat, added sugars, sodium) [18] [5].

- Recommended Food Groups: Core food groups to encourage (e.g., fruits, vegetables, whole grains, dairy, nuts, legumes) [21] [18].

- Step 3: Map NP Model Components: Create a matrix comparing the model's "nutrients to encourage," "food groups to encourage," and "nutrients to limit" against the lists generated in Step 2 [10]. The model demonstrates higher content validity if its components show strong overlap with the guideline's priorities [17].

Methodology for Diet-Level Predictive Validation

This method validates an NP model by assessing its ability to predict overall diet quality when applied across a person's total diet [18].

- Step 1: Collect Dietary Intake Data: Use high-quality, national dietary survey data, such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), which includes 24-hour dietary recalls [20] [18].

- Step 2: Calculate NP Model Scores: Apply the NP model to each food in the database. For each individual, calculate a total diet score, typically by summing the scores of all consumed foods, often energy-weighted [18].

- Step 3: Calculate Reference Diet Quality Score: Compute an established diet quality index for each individual, such as the Healthy Eating Index (HEI-2015) or the Alternate Healthy Eating Index (AHEI), which are directly based on dietary guidelines [20] [18].

- Step 4: Statistical Correlation: Analyze the correlation (e.g., using Pearson correlation coefficient) between the individuals' total NP model scores and their HEI-2015 or AHEI scores. A strong, significant correlation provides evidence that the NP model is a valid proxy for overall adherence to dietary guidelines [18].

Methodology for Diagnostic Accuracy Validation via ROC Analysis

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis determines how well a continuous NP score can diagnose a food as "healthy" according to a benchmark model [18].

- Step 1: Select a Reference Classifier: Choose an established NP model or set of criteria (e.g., an "A" Nutri-Score or a "5-star" HSR rating) to serve as the binary classifier of "healthier" foods [18].

- Step 2: Calculate Scores and Define Status: For a large, representative food database, calculate both the new NP model's continuous score and the binary classification from the reference model.

- Step 3: Perform ROC Analysis: Plot the ROC curve, which shows the trade-off between sensitivity (correctly identifying healthy foods) and specificity (correctly identifying less-healthy foods) across all possible score cut-offs of the new model.

- Step 4: Calculate Area Under the Curve (AUC): The AUC quantifies the model's diagnostic accuracy. An AUC > 0.90 is considered excellent, indicating high agreement with the reference model [18].

Diagram Title: Content Validity Assessment Workflow

Successful development and validation of NP models require specific data and analytical tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for NP Model Validation

| Tool/Resource | Function in Validation | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|

| National Nutrient Databases | Provides detailed nutrient composition data for foods to calculate NP scores. | USDA FoodData Central [17], Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies (FNDDS) [18] [17], Japanese Food Standard Composition Table [5]. |

| Dietary Intake Surveys | Supplies data on real-world food consumption for diet-level predictive validation. | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) [20] [18]. |

| Food Pattern Equivalents Databases (FPED) | Allows translation of foods into servings of dietary guideline-based food groups (e.g., cups of fruit, oz. whole grains). | USDA FPED [18]. |

| Validated Diet Quality Indices | Serves as a reference standard for assessing the predictive validity of an NP model at the diet level. | Healthy Eating Index (HEI) [18], Alternate Healthy Eating Index (AHEI) [20]. |

| Established NP Models | Acts as a reference classifier for diagnostic accuracy tests (ROC analysis) and convergent validity studies. | Nutri-Score [10] [18], Health Star Rating (HSR) [18], Ofcom model [10]. |

| Statistical Analysis Software | Performs correlation analyses, ROC curve analysis, kappa statistics, and other essential validation tests. | R, Python, SAS, SPSS. |

The comparative analysis reveals that models like the bHNDS and Meiji NPS explicitly incorporate both nutrients and food groups to encourage, aligning closely with the food-based recommendations of modern dietary guidelines [18] [5]. In contrast, other models place a stronger, sometimes exclusive, emphasis on nutrients to limit [10] [17]. The choice of model and interpretation of its content validity must therefore be informed by the specific public health priorities it aims to address [17]. For instance, models for populations facing childhood undernutrition or micronutrient deficiencies must prioritize adequate intake of essential nutrients, while those for populations with high NCD prevalence may justifiably focus more on limiting excess consumption [5] [19] [17].

In conclusion, assessing content validity through alignment with dietary guidelines is a fundamental first step in ensuring the scientific soundness and public health relevance of NP models. Researchers and policymakers are encouraged to employ the multi-faceted experimental protocols and tools outlined in this guide to critically evaluate existing models and inform the development of future models, particularly for vulnerable populations and diverse food systems.

Nutrient profiling (NP) represents a critical public health tool, defined as the "science of classifying or ranking foods according to their nutritional composition for reasons related to preventing disease and promoting health" [23]. The proliferation of NP models worldwide has accelerated dramatically, with 26 new government-led models identified between 2016-2020 alone [4]. This expansion reflects growing recognition that NP models provide essential scientific underpinning for diverse nutrition policies—from front-of-pack labeling (FOPL) and marketing restrictions to food procurement standards and taxation regimes [4].

The global landscape of NP frameworks now features prominent systems including the United Kingdom's Ofcom model (developed for regulating food marketing to children), Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) Nutrient Profiling Scoring Criterion (for regulating health claims), and various Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and World Health Organization (WHO) regional frameworks that adapt global guidance to local contexts [24] [25] [4]. This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of these major NP models, examining their structural designs, validation methodologies, applications, and performance across diverse food categories for researchers and scientific professionals.

Comparative Analysis of Major Nutrient Profiling Models

Key Characteristics and Structural Designs

Table 1: Structural Comparison of Major Nutrient Profiling Models

| Model Characteristic | FSANZ NPSC | Ofcom (UK) | PAHO/WHO Regional Frameworks | Food Compass 2.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Regulating health claims [24] | Food marketing to children [4] | Front-of-pack labeling, various policy applications [26] [4] | Comprehensive food rating [2] |

| Scoring Basis | Points based on energy, saturated fat, sodium, sugar with deductions for positive components [25] | Points based on nutrients to limit with deductions for positive elements [4] | Varies by region; often adapted from existing models [4] | 100-point scale across 9 holistic domains [2] |

| Nutrients to Limit | Energy, saturated fat, sodium, total sugars [24] | Sodium, saturated fat, total sugars [4] | Typically sodium, saturated fat, total sugars [23] | Multiple including added sugars, sodium, processing aspects [2] |

| Positive Elements | Protein, dietary fiber, fruit, vegetable, nut, legume content [24] | Fruit, vegetable, nut, legume content [4] | Varies; may include fiber, protein, fruits/vegetables [23] | Fiber, whole fruits, vegetables, legumes, specific healthy components [2] |

| Food Categorization | Categorical approach with different thresholds | Categorical approach | Often categorical with category-specific thresholds [23] | Universal scoring across categories [2] |

| Validation Status | Government-endorsed standard [24] | Government-endorsed standard [4] | Implemented in multiple Latin American countries [26] [23] | Validated against health outcomes [2] |

Regional Implementation and Adaptation

The global proliferation of NP models demonstrates both shared principles and significant regional adaptations. Latin American and Caribbean countries have particularly embraced front-of-pack labeling schemes, with 16 LMICs implementing various FOPL policies by 2023 [23]. These regional frameworks often build upon existing models while incorporating local dietary patterns and public health priorities.

In Latin America, 'High In' warning labels have become predominant, implemented in countries including Peru, Mexico, and Brazil [23]. These systems typically focus on identifying foods high in critical nutrients of concern—sodium, saturated fats, and total sugars—using relatively simple, binary criteria that facilitate consumer understanding [23]. By contrast, the Traffic Light scheme implemented in Ecuador and Sri Lanka provides a more graded assessment of nutrient levels [23], while Choices schemes in South Asia primarily highlight the healthiest options within categories [23].

Table 2: Regional Applications of Nutrient Profiling Models

| Region/Country | Primary Model Type | Key Applications | Notable Adaptations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia/NZ | FSANZ NPSC | Health claim regulation [24] | Specific scoring algorithm with category adjustments |

| United Kingdom | Ofcom | Marketing restrictions to children [4] | Basis for multiple international adaptations |

| Latin America | PAHO-informed 'High In' labels | Front-of-pack labeling [23] | Emphasis on critical nutrients of concern |

| United States | Food Compass 2.0 | Comprehensive food rating [2] | Multi-domain approach including processing |

| Multiple LMICs | Various FOPL systems | Labeling, marketing restrictions [4] | Adapted from established models with local modifications |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Validation Against Health Outcomes

Robust validation represents a critical component of NP model development, with leading frameworks employing diverse methodological approaches:

Food Compass 2.0 Validation Protocol: Researchers conducted comprehensive validation against health outcomes in a nationally representative population of 47,099 US adults [2]. The protocol calculated an energy-weighted average Food Compass score (i.FCS) for each individual's dietary intake, then examined associations with health parameters using multivariable-adjusted regression models. Key metrics included body mass index, blood pressure, lipid profiles, blood glucose levels, and prevalence of metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all-cause mortality [2]. The i.FCS demonstrated strong correlation with the Healthy Eating Index-2015 (r=0.78), supporting its criterion validity [2].

LMICs FOPL Impact Assessment: A 2025 study analyzed 327,194 packaged food products across 19 LMICs from 2015-2023 to evaluate nutritional quality changes following FOPL implementation [23]. Researchers extracted on-pack nutritional information from the Mintel Global New Product Database (GNPD), focusing on top food categories representing nearly half of newly launched packaged foods in these markets [23]. Statistical analysis compared median nutrient content across three-year periods (2015-2017, 2018-2020, 2021-2023) using t-tests with Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple testing [23]. Difference-in-difference analysis further assessed nutrient content changes in countries implementing FOPL versus those without such policies [23].

Model Development and Testing Protocols

Systematic Review Methodology: A 2023 systematic review identified NP models through structured searches of seven peer-reviewed databases and one grey literature database [4]. The protocol followed PRISMA guidelines with pre-established eligibility criteria focusing on government-led models for nutrition policy applications [4]. Two independent reviewers assessed publications, with models classified by application type, nutrient components, scoring methodology, and validation status [4].

Food Compass 2.0 Development: The updated system incorporated emerging evidence on specific ingredients and diet-health relationships [2]. Revisions included enhanced assessment of food processing (providing positive points for non-ultraprocessed foods rather than only penalizing ultraprocessed foods), updated evaluation of dairy fat based on recent evidence, and improved accounting for added sugars as both additives and ingredients [2]. The system also integrated newly available data on artificial additives, resulting in score reductions for highly processed products containing multiple additives [2].

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Nutrient Profiling Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Research Function | Key Applications in NP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial Food Databases | Mintel Global New Product Database (GNPD) [23] | Tracking new product introductions and nutritional composition | Monitoring food supply changes, reformulation trends |

| Computational Algorithms | FSANZ Nutrient Profiling Scoring Calculator [24] | Standardized NP score calculation | Regulatory compliance assessment |

| Validation Metrics | Healthy Eating Index-2015 [2] | Criterion validation reference | Establishing convergent validity |

| Statistical Packages | R, Python, SAS | Difference-in-difference analysis, multivariate modeling [23] | Policy impact assessment, health outcome validation |

| Health Outcome Databases | NHANES, cohort studies [2] | Population health data linkage | Association studies with morbidity/mortality |

Signaling Pathways and Conceptual Frameworks

Figure 1: Logical framework depicting the cyclical process of nutrient profiling model development, implementation, and refinement based on policy needs and health impact assessment.

Figure 2: Conceptual workflow of nutrient profiling systems from data inputs to policy applications, demonstrating the transformation of nutritional data into regulatory decisions.

Performance Across Food Categories and Policy Applications

Model Performance in Different Food Categories

Food Category-Specific Performance: Different NP models demonstrate variable performance across food categories, reflecting their distinct design philosophies and intended applications. The Food Compass 2.0 system shows particularly nuanced differentiation, with most seafood (82%), legumes (80%), nuts (89%), vegetables (63%), and fruits (53%) scoring ≥70 points (on a 100-point scale), while most beverages (54%) and animal fats (92%) score ≤30 [2]. Recent updates to Food Compass resulted in notable score increases for minimally processed animal foods including seafood (72 to 81), beef (33 to 44), pork (35 to 44), and eggs (46 to 54), while scores decreased for processed cereals, plant-based dairy alternatives (54 to 43), and cereal bars (42 to 34) [2].

Impact on Food Reformulation: Evidence from LMICs demonstrates that FOPL implementation correlates with measurable improvements in the nutritional quality of packaged foods. From 2015-2023, products in countries with FOPL policies showed significant reductions in total sugars and, depending on the scheme type, sodium reduction [23]. Category-level analysis revealed that packaged meat and coffee products increased as a percentage of food supply, while more indulgent categories like cookies declined [23]. The specific type of FOPL scheme influences reformulation patterns, with 'High In' labels associated with different nutrient changes compared to Traffic Light or Choices systems [23].

Policy Effectiveness and Public Health Impact

Validation Against Dietary Quality: When extended to score complete diets, NP models demonstrate significant associations with health outcomes. Each standard deviation (10.8 points) increase in the individual Food Compass Score (i.FCS) associated with lower BMI (-0.56 kg/m²), improved blood pressure, lipid profiles, and glycemic measures, along with 8-14% lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and lung disease [2]. Most significantly, higher i.FCS associated with 24% lower all-cause mortality between highest and lowest quintiles [2].

Consumer Understanding and Behavior: Research on FOPL systems indicates variable effectiveness based on design complexity. Peruvian 'High In' labels demonstrated effectiveness across diverse socioeconomic groups [23], while Ecuador's Traffic Light system showed high comprehension but inconsistent behavioral impact [23]. This suggests that while simpler, binary warning labels may more effectively drive healthier choices across population segments, more complex systems provide nuanced information that doesn't necessarily translate to behavioral change.

The global proliferation of NP models from Ofcom and FSANZ to PAHO and WHO regional frameworks represents a dynamic response to escalating diet-related non-communicable disease burdens worldwide. The evidence reviewed demonstrates that while core nutritional principles remain consistent across models, successful implementation requires contextual adaptation to regional dietary patterns, public health priorities, and regulatory environments.

Future research priorities should include: (1) longitudinal studies examining how NP-guided policies influence dietary patterns and health outcomes over time; (2) standardized validation protocols enabling direct comparison of model performance across diverse populations; and (3) integration of emerging evidence on food processing, additives, and non-nutrient bioactive compounds. As NP models evolve toward increasingly sophisticated algorithms, maintaining a balance between scientific precision and practical implementability remains essential for maximizing public health impact.

For researchers and policymakers, selection of appropriate NP models requires careful consideration of specific application contexts, target populations, and available implementation resources. The continuing global experimentation with diverse NP frameworks provides valuable natural experiments that will further refine our understanding of how to optimally characterize food healthfulness for different policy objectives.

Nutrient profiling models (NPMs) have become fundamental tools in public health nutrition, providing scientific methods to classify foods based on their nutritional composition. The World Health Organization defines nutrient profiling as "the science of classifying or ranking foods according to their nutritional composition for reasons related to preventing disease and promoting health" [5]. These models serve critical functions in front-of-pack labeling, marketing restrictions, product reformulation, and consumer education. Recent years have witnessed a remarkable expansion in NPM development, with a systematic review identifying 26 new government-endorsed models in just a four-year period (2016-2020) [4]. This rapid proliferation underscores an urgent need for robust validation frameworks to ensure these models deliver meaningful health outcomes beyond theoretical development.

The escalating health burdens of diet-related non-communicable diseases have intensified the demand for effective nutritional assessment tools [2]. As regulatory agencies and food manufacturers increasingly rely on NPMs to guide policy and product development, the scientific community faces a pressing question: how do we move from model creation to demonstrated real-world efficacy? This review examines the current state of NPM validation, compares methodological approaches, and identifies critical gaps in translating algorithmic performance into tangible health impacts.

Comparative Analysis of Major Nutrient Profiling Systems

Model Architectures and Algorithmic Approaches

Current nutrient profiling systems employ diverse algorithmic approaches, ranging from category-specific thresholds to across-the-board scoring systems. The two most prevalent grading schemes—Nutri-Score and Health Star Rating (HSR)—both evolved from the United Kingdom's Ofcom Nutrient Profiling System yet demonstrate important structural differences [27]. Nutri-Score employs a 5-color graded front-of-pack label ranging from A (dark green, healthiest) to E (dark orange, least healthy), while HSR uses a monochrome system with 10 possible star grades from 0.5 to 5 stars [27]. Although both systems share a common ancestry, adaptations during development have resulted in meaningful differences in how food products are evaluated and presented to consumers.

More comprehensive systems like Food Compass 2.0 incorporate multiple holistic domains, including nutrient ratios, food ingredients of health relevance, and processing characteristics—all assessed per 100 kcal rather than food weight to avoid confounding by water content [2]. This multidimensional approach aims to address limitations of earlier models that focused predominantly on negative nutrients. Meanwhile, category-specific models like the Keyhole system or various World Health Organization regional models establish different thresholds for different food categories, acknowledging that what constitutes a "healthy" profile varies across food types [28].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

A large-scale comparison of Nutri-Score and HSR using 17,226 pre-packed foods from the Slovenian food supply demonstrated generally strong alignment between these systems, with 70% agreement and a very strong correlation (Spearman rho = 0.87) [27]. However, significant divergences emerged in specific food categories, particularly cooking oils and cheeses. For instance, in the cooking oils category, agreement dropped to just 27% (kappa = 0.11, rho = 0.40), with Nutri-Score favoring olive and walnut oils while HSR awarded higher ratings to grapeseed, flaxseed, and sunflower oils [27]. Similarly, for cheeses and processed cheese products, HSR classified most products (63%) as healthy (≥3.5 stars), while Nutri-Score predominantly assigned lower scores [27].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Major Nutrient Profiling Models

| Model | Classification Approach | Key Nutrients Assessed | Validation Status | Notable Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutri-Score | Across-the-board (5-tier) | Negative: energy, sugars, SFA, sodium; Positive: fruits, vegetables, fiber, protein | Extensive European validation; associated with biomarkers | Favors olive oil; less aligned for dairy [27] |

| Health Star Rating (HSR) | Across-the-board (10-star) | Negative: energy, SFA, sugars, sodium; Positive: fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, protein, fiber | Validated in Australian context; sales-weighted analyses | Favors seed oils; inconsistent cheese scoring [27] |

| Food Compass 2.0 | Multidimensional (100-point scale) | 9 domains including nutrient ratios, ingredients, processing, additives | Associated with health outcomes and mortality in US cohort [2] | Complex algorithm; recent update requiring further validation [2] |

| WHO Regional Models | Category-specific thresholds | Varies by region; typically energy, SFA, sugars, sodium | Face validity testing; marketing restriction focus | Limited discriminant validation against health outcomes [4] |

| Meiji NPS | Life-stage specific scoring | Age-appropriate nutrients to encourage and limit | Convergent validation against NRF9.3 and WHO models [5] | Industry-developed; Japan-specific focus [5] |

The updated Food Compass 2.0 system demonstrates enhanced characterization of food healthfulness, with 23% of products scoring ≥70 (compared to 22% previously), 46% scoring 31-69 (unchanged), and 31% scoring ≤30 (previously 33%) [2]. When extended to score individual diets, each 10.8-point higher energy-weighted average Food Compass score was associated with more favorable BMI (-0.56 kg/m²), systolic blood pressure (-0.55 mm Hg), LDL cholesterol (-1.49 mg/dL), and hemoglobin A1c (-0.02%) after multivariable adjustment [2].

Validation Methodologies: Experimental Protocols and Biomarker Assessment

Validation Against Health Outcomes

The most robust validation approaches examine relationships between NPM scores and direct health outcomes. The Food Compass 2.0 validation analyzed data from 47,099 US adults, calculating energy-weighted average Food Compass scores (i.FCS) for each participant's diet [2]. Researchers employed multivariable adjusted models to assess associations between i.FCS and numerous health parameters, including anthropometric measures, blood pressure, lipid profiles, glycemic markers, and prevalent disease conditions. This comprehensive approach demonstrated that higher i.FCS scores significantly correlated with lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome (OR 0.86), cardiovascular disease (OR 0.92), cancer (OR 0.93), and all-cause mortality (HR 0.92 per 1 standard deviation) [2].

The PREDISE study conducted a cross-sectional analysis of 1,019 French-Canadian adults to evaluate three NPMs (HSR, Nutri-Score, and Nutrient-Rich Food index 6.3) against both diet quality measures and cardiometabolic risk factors [29]. Researchers used web-based self-administered 24-hour recalls to calculate energy-weighted individual scores for each model, then employed multivariable linear models to assess associations with the Healthy Eating Food Index 2019 and 14 biomarkers covering anthropometry, blood pressure, blood lipids, glucose homeostasis, and inflammation [29]. This methodology provided a robust framework for comparing model performance against objective health indicators.

Analytical Techniques for Nutritional Assessment

Validation of nutrient profiling models relies on sophisticated analytical techniques to accurately determine food composition. Chromatographic methods, particularly gas chromatography (GC) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), enable precise quantification of fatty acids, sterols, aroma components, and contaminants [30]. These techniques separate complex mixtures into individual components based on their differential partitioning between mobile and stationary phases, with the partition coefficient expressed as Kx = [C]s/[C]m, where [C]s and [C]m are concentrations in stationary and mobile phases, respectively [30].

Molecular assays and metabolomics approaches provide additional layers of compositional data, detecting micronutrients, bioactive compounds, and potential contaminants. These bioanalytical methods have become increasingly important for verifying label accuracy and detecting undisclosed ingredients that may affect a product's health profile [30]. As food matrices grow more complex with reformulation efforts, advanced analytical techniques become essential for validating that theoretical nutrient profiles correspond to actual compositional data.

Figure 1: Comprehensive validation workflow for nutrient profiling models, illustrating the sequential phases from development through real-world application with feedback mechanisms for iterative refinement.

Critical Gaps in Current Validation Practices

Limited Biomarker Correlation and Health Outcome Data

Despite proliferation of NPMs, a critical gap exists between theoretical model development and robust validation against hard health endpoints. Systematic reviews indicate that only approximately 42% of government-endorsed NPMs have undergone any form of content or face validity testing [4]. Even fewer have been validated against biomarkers or health outcomes in diverse populations. The PREDISE study found that while higher quality scores from all three evaluated models (HSR, Nutri-Score, NRF6.3) associated with better diet quality, associations with biomarkers were inconsistent across models [29]. For instance, original HSR and Nutri-Score associated with lower waist circumference and HOMA-IR, but replacing total sugars with free sugars in the algorithms only slightly increased the number of associations observed with biomarkers [29].

This validation gap is particularly concerning for vulnerable populations. A study of child-targeted packaged foods in Türkiye found that 93.2% of products did not comply with WHO NPM-2023 criteria and should not be marketed to children, with most classified as Nutri-Score D and E (70%) and ultra-processed (92.7%) [12]. However, limited research has validated whether these models accurately predict actual health outcomes in pediatric populations, highlighting a significant evidence gap.

Contextual and Cultural Applicability Limitations

Many nutrient profiling models fail to account for regional dietary patterns, cultural contexts, and life-stage nutritional requirements. While the WHO emphasizes the importance of developing NPMs tailored to country-specific health issues and food cultures [28], implementation of this principle remains inconsistent. Japan's development of NPM-PFJ (1.0) represents a purposeful adaptation of the HSR system to align with Japanese food culture and policies, revising reference values for energy, saturated fat, total sugars, sodium, protein, and dietary fiber while maintaining reference values for fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes [28]. Similarly, the Meiji Nutritional Profiling System addresses life-stage differences, creating distinct algorithms for younger children (3-5 years) and older children (6-11 years) to support proper growth and development while preventing childhood overweight [5].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Nutrient Profiling Validation

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Validation | Application Examples | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Composition Databases | Provide standardized nutrient data for scoring | USDA FNDDS, Japanese Food Standard Composition Table, Branded food databases | Currency, completeness, analytical method standardization [5] [31] |

| Chromatographic Systems | Separation and quantification of food components | GC for fatty acids, sterols; HPLC for vitamins, additives | Sensitivity, resolution, reference standards availability [30] |

| Dietary Assessment Tools | Capture individual food consumption patterns | 24-hour recalls, food frequency questionnaires, food records | Memory bias, portion size estimation, coding consistency [29] |

| Biomarker Panels | Objective health status indicators | Lipids, glycemic markers, inflammatory markers, blood pressure | Biological variability, cost, standardization across laboratories [2] [29] |

| Sales Data | Market-share weighting for real-world impact | Nationwide retail scanner data, household panel data | Representativeness, matching accuracy, privacy considerations [27] |

| Metabolomics Platforms | Comprehensive chemical fingerprinting | Identification of novel bioactive compounds, processing markers | Computational infrastructure, compound identification challenges [30] |

The development of nutrient profiling models has outpaced rigorous validation against meaningful health outcomes. While comparative studies show reasonable correlation between major models like Nutri-Score and HSR, significant discrepancies in specific food categories highlight the need for standardized validation protocols [27]. The forward progression of the field requires a shift from theoretical model development to comprehensive real-world validation incorporating biomarker assessment, health outcome correlation, and evaluation of intended policy impacts.

Future validation efforts should prioritize several critical areas: (1) longitudinal studies examining relationships between model scores and hard health endpoints across diverse populations; (2) methodological standardization to enable cross-model comparisons; (3) development of life-stage and population-specific validation frameworks; and (4) assessment of real-world impacts on consumer behavior, product reformulation, and health outcomes at the population level. Only through such comprehensive validation can nutrient profiling fulfill its potential as a evidence-based tool for addressing diet-related chronic diseases and promoting public health nutrition.

From Theory to Practice: Methodological Approaches and Contextual Application of NP Models

Nutrient profiling (NP) models are algorithmic tools that classify foods based on their nutritional composition to support public health goals [10]. The validation of these models is critical for ensuring they accurately predict health outcomes and are effectively applied in policies such as front-of-pack labeling (FOPL) and food reformulation [3] [10]. This guide objectively compares the performance of major nutrient profiling systems by examining their algorithmic structures, validation evidence, and agreement across food categories.

The core algorithmic structures in nutrient profiling can be categorized into three primary types:

- Points-Based Systems: Assign positive and negative points for nutrients to encourage and limit, then sum for total score

- Threshold Models: Establish cutoff values for specific nutrients to define "healthier" foods

- Continuous Scoring: Generate continuous scores that rank foods on a spectrum

Comparative Analysis of Major Nutrient Profiling Models

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, algorithmic structures, and validation evidence for major nutrient profiling models implemented globally:

Table 1: Comparison of Major Nutrient Profiling Models

| Model Name | Algorithmic Structure | Key Components | Primary Application | Validation Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutri-Score | Points-Based System | Nutrients to limit: energy, saturated fat, sugars, sodium; Nutrients to encourage: protein, fiber, fruits/vegetables/nuts | Front-of-pack labeling (Europe) | Substantial criterion validation [3] |

| Health Star Rating (HSR) | Points-Based System | Adapted from Ofcom; nutrients to limit and encourage with extended score scales | Front-of-pack labeling (Australia/New Zealand) | Intermediate criterion validation [3] |

| Food Standards Agency (FSA-NPS) | Points-Based System | Basis for Nutri-Score; energy, saturated fat, sugars, sodium, fiber, protein, fruits/vegetables/nuts | Marketing restrictions (UK) | Intermediate criterion validation [3] |

| WHO WPRO Model | Threshold Model | Category-specific thresholds for fats, sugars, sodium; defines "unhealthy" foods | Marketing restrictions to children (Western Pacific) | Reference standard for content validity [5] |

| Meiji NPS | Continuous Scoring | Calculates ratios of nutrients relative to reference daily values; age-specific algorithms | Product reformulation (Japan) | Convergent validation against NRF9.3 and WHO model [5] |

| Nutrient-Rich Food (NRF) Index | Continuous Scoring | Sum of percentage daily values for nutrients to encourage minus nutrients to limit | Scientific research | Intermediate criterion validation [3] |

Validation Evidence for Health Outcome Prediction

The most robust validation evidence comes from prospective studies examining associations between NP model scores and health outcomes. The following table summarizes the criterion validation evidence for NP models based on systematic review and meta-analysis findings:

Table 2: Criterion Validation Evidence for Nutrient Profiling Models

| Model Name | Health Outcome Associations | Strength of Evidence | Key Research Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutri-Score | Significantly lower risk of CVD, cancer, all-cause mortality, and BMI increase | Substantial | Highest vs. lowest diet quality: CVD HR=0.74; cancer HR=0.75; all-cause mortality HR=0.74 [3] |

| Health Star Rating | Associated with diet quality and some biomarkers | Intermediate | Associated with BMI, diastolic blood pressure, triglycerides in cross-sectional analysis [29] |

| FSA-NPS | Associated with chronic disease risk | Intermediate | Used as basis for other validated models [3] |

| NRF Index | Associated with diet quality metrics | Intermediate | Strong correlation with Meiji NPS (r=0.73) [5] |

| WHO Models | Content validity established | Variable by region | Used as reference standard for many validations [5] [10] |

A 2025 study examined whether replacing total sugars with free sugars in NP algorithms improved model performance, testing this modification in three models (HSR, Nutri-Score, NRF6.3). The results showed that while all three original models were associated with better diet quality and improved cardiometabolic risk factors, replacing total sugars with free sugars only slightly increased the number of associations observed with biomarkers, providing limited support for this algorithmic modification [29].

Methodological Approaches for Model Validation

Experimental Protocols for Validation Studies

Researchers employ several methodological frameworks to validate NP models:

Criterion Validation Protocol:

- Study Design: Prospective cohort studies tracking dietary intake and health outcomes

- Population: Large, diverse participant groups with long-term follow-up

- Exposure Assessment: Calculate individual NP scores using weighted food consumption data