Wearable Sensors vs. 24-Hour Recall: A Comparative Analysis for Modern Dietary Assessment in Research and Clinical Trials

Accurate dietary assessment is critical for nutritional research, chronic disease management, and evaluating interventions in drug development.

Wearable Sensors vs. 24-Hour Recall: A Comparative Analysis for Modern Dietary Assessment in Research and Clinical Trials

Abstract

Accurate dietary assessment is critical for nutritional research, chronic disease management, and evaluating interventions in drug development. This article provides a comprehensive comparison between two evolving methodologies: technology-assisted 24-hour dietary recalls (24HR) and wearable sensors. We explore the foundational principles of each method, detailing their operational mechanisms and technological advancements, including AI-assisted tools and passive monitoring devices. The analysis covers application-specific best practices, common pitfalls with optimization strategies, and a critical review of validation studies and performance metrics. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes evidence to guide the selection and implementation of robust dietary assessment tools for rigorous scientific and clinical applications.

The Evolution of Dietary Monitoring: From Traditional Recall to Wearable Sensors

The Critical Need for Accurate Dietary Data in Clinical Research and Drug Development

Accurate dietary data is a cornerstone for advancing clinical research and developing effective drugs, particularly for conditions like obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. Traditional methods of dietary assessment, such as the 24-Hour Dietary Recall (24HR), have long been the standard but are increasingly being complemented or challenged by innovative wearable sensor technologies. This guide provides a objective comparison of these methodologies, focusing on their performance, underlying protocols, and applicability in rigorous research settings.

Performance Comparison: Wearable Sensors vs. 24-Hour Dietary Recall

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent validation studies, highlighting the relative strengths and weaknesses of each method.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Dietary Assessment Methods

| Methodology | Study/System Name | Key Performance Metric | Reported Result | Context & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wearable Camera (AI-Assisted) | EgoDiet (Study in Ghana) [1] [2] | Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) for portion size | 28.0% | Compared to 24HR; shows improvement over traditional method. |

| Traditional 24HR | 24-Hour Dietary Recall (Study in Ghana) [1] [2] | Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) for portion size | 32.5% | Served as the baseline for comparison with the wearable system. |

| Web-Based 24HR | myfood24 (Danish Adults) [3] | Correlation with Urinary Potassium (ρ) | 0.42 | A moderate correlation with a biomarker for potassium intake. |

| Web-Based 24HR | myfood24 (Danish Adults) [3] | Correlation with Serum Folate (ρ) | 0.49 | A moderate correlation with a biomarker for folate intake. |

| Image-Voice System | VISIDA (Cambodian Mothers) [4] | Mean Difference in Energy Intake vs. 24HR (kcal) | -296 | Systematically estimated lower energy intake than 24HR. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Understanding the experimental design behind the data is crucial for interpreting results and selecting appropriate methods for future studies.

Protocol for Validating AI-Enabled Wearable Cameras (EgoDiet)

The EgoDiet system was designed as a passive, egocentric vision-based pipeline to estimate food portion sizes, specifically optimized for African cuisines [1] [2].

- Data Collection: Researchers used two low-cost, wearable cameras: the AIM (attached to eyeglasses) and the eButton (worn on the chest). These devices continuously captured images during eating episodes in controlled and free-living settings among populations of Ghanaian and Kenyan origin [1] [2].

- AI Processing Pipeline:

- EgoDiet:SegNet: A neural network based on Mask R-CNN performed segmentation of food items and containers from the image stream [1].

- EgoDiet:3DNet: A depth estimation network reconstructed 3D models of the containers to determine scale without depth-sensing cameras [1].

- EgoDiet:Feature: This module extracted portion size-related features, such as the Food Region Ratio (FRR) and Plate Aspect Ratio (PAR), to account for different camera angles [1].

- EgoDiet:PortionNet: The final module estimated the consumed portion size (in weight) by leveraging the extracted features, addressing the challenge of limited training data [1].

- Validation: The weight estimates from the EgoDiet pipeline were compared against measurements taken by dietitians and data from traditional 24HR interviews. The Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) was the primary metric for comparison [1] [2].

Protocol for Validating Web-Based Dietary Recall Tools (myfood24)

The myfood24 system is an automated, web-based tool that supports both self-administered and interviewer-led 24-hour dietary recalls and food records [3].

- Study Design: In a study of healthy Danish adults, participants completed two 7-day weighed food records (WFR) using the myfood24 app, four weeks apart. This design tested both validity and reproducibility [3].

- Objective Validation Measures: Unlike many studies that rely on cross-comparison with other self-reported methods, this study used objective biomarkers as a reference:

- Energy Metabolism: Resting energy expenditure was measured via indirect calorimetry, and the Goldberg cut-off was applied to identify mis-reporters [3].

- Biomarker Analysis: Fasting blood samples were analyzed for serum folate, and 24-hour urine samples were analyzed for urea (protein intake biomarker) and potassium [3].

- Statistical Analysis: The validity of the tool was assessed by correlating the nutrient intakes estimated by myfood24 with the concentration of the corresponding biomarkers (e.g., folate intake vs. serum folate) using Spearman's rank correlation (ρ) [3].

Protocol for a Multi-Technology Study (CoDiet)

The CoDiet study protocol illustrates a comprehensive approach to understanding diet-disease relationships by integrating multiple technologies [5].

- Enhanced Surveillance: Participants wear wearable cameras and activity monitors for three separate one-week periods at home. This captures objective data on dietary intake, physical activity, and sleep patterns [5].

- Multi-Omics and Health Analysis: At the end of each monitoring period, participants undergo detailed clinical assessments, including:

- Body composition analysis.

- Cardiovascular disease risk assessment via Advanced Glycation End products (AGE) and accelerated photoplethysmography (APG).

- Collection of blood, urine, stool, and breath samples for multi-omics analysis [5].

- Qualitative Feedback: In-depth interviews are conducted to gauge participant perception and acceptability of the novel monitoring technologies [5].

Decision Framework for Method Selection

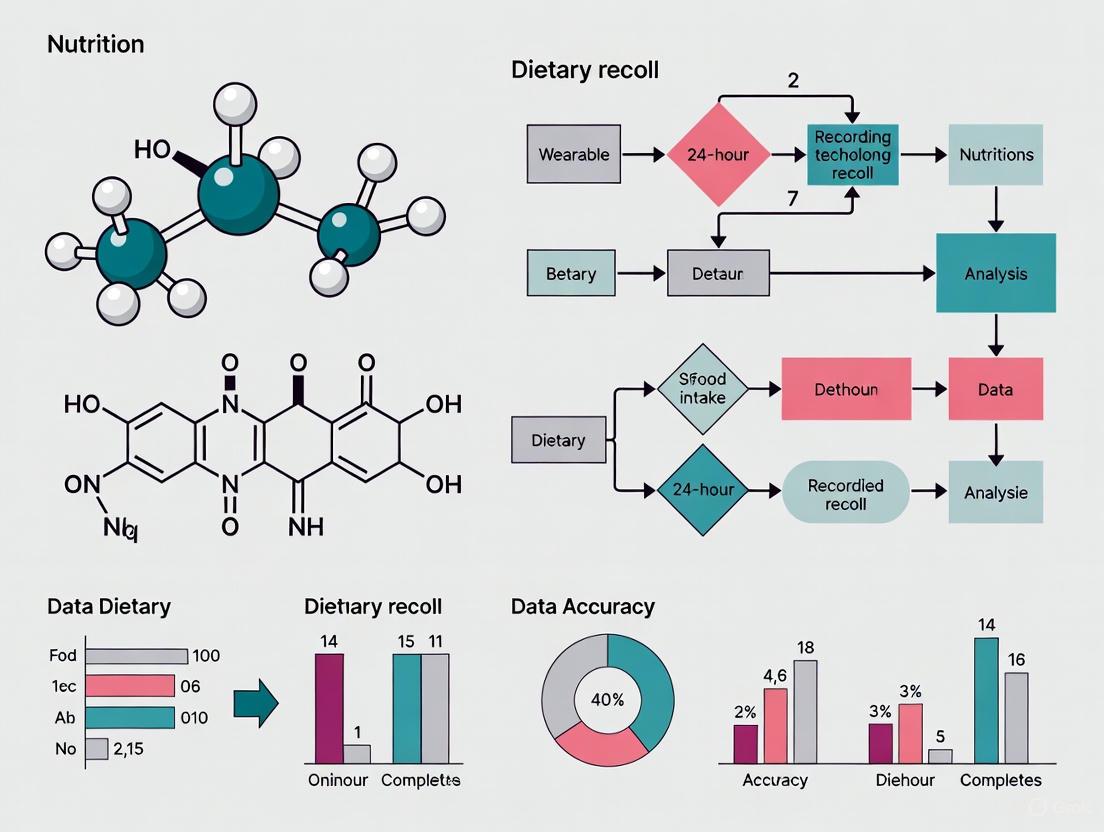

The choice between wearable sensors and traditional recalls depends on the research objectives, population, and resources. The following diagram outlines key decision pathways.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential tools and technologies used in modern dietary assessment research, as featured in the cited studies.

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Dietary Assessment

| Tool / Technology | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Wearable Egocentric Cameras (e.g., AIM, eButton) [1] [2] | Passively captures first-person-view images of eating episodes and food environments, minimizing participant burden and recall bias. | Continuous dietary monitoring in free-living populations in LMICs; estimating portion sizes via AI. |

| AI-Based Image Analysis Pipeline (e.g., EgoDiet:SegNet, 3DNet) [1] | Automates food item segmentation, 3D container reconstruction, and portion size estimation from image data. | Objectively quantifying food intake from wearable camera footage without manual annotation. |

| Web-Based Dietary Recall Platforms (e.g., myfood24, Foodbook24) [3] [6] | Streamlines the collection and nutrient analysis of 24-hour recall data; can be customized with multi-language support and expanded food lists. | Assessing nutrient intakes in large-scale studies and diverse populations with different dietary habits. |

| Dietary Intake Biomarkers (e.g., Serum Folate, Urinary Nitrogen/Potassium) [3] | Provides an objective, biological measure of nutrient intake to validate the accuracy of self-reported dietary data. | Validating the relative validity of a new dietary assessment tool like myfood24. |

| Clinical-Grade Wearable Sensors (e.g., Hexoskin Shirt, CardioWatch) [7] [8] | Continuously monitors physiological vital signs (heart rate, respiration) and activity alongside dietary intake for a holistic health picture. | Predicting clinical deterioration in hospital patients [7] or validating heart rate in pediatric cardiology [8]. |

| Multi-Omics Analysis (e.g., Metabolomics of blood/urine) [5] | Characterizes the biochemical state of an individual, offering deep insights into the physiological impacts of diet. | Integrating with dietary intake data to explore mechanisms linking diet to non-communicable diseases. |

In conclusion, the evolution from traditional 24HR to wearable sensors and sophisticated web-based platforms represents a significant leap toward obtaining more objective and accurate dietary data. The choice of method is not one-size-fits-all but should be strategically aligned with the research question, with a growing trend toward integrating multiple technologies to capture the complex role of diet in health and disease.

This guide provides an objective comparison of the traditional 24-hour dietary recall (24HR) method against the emerging technology of wearable cameras for dietary assessment, contextualized for research and drug development applications.

Core Principles of the 24-Hour Dietary Recall

The 24-hour dietary recall (24HR) is a structured interview designed to capture detailed information about all foods and beverages consumed by a respondent in the previous 24 hours, typically from midnight to midnight [9].

- Purpose and Description: The primary goal is to obtain a detailed snapshot of dietary intake for a given day. It is an open-ended method that prompts respondents for comprehensive details, moving from general categories to specific descriptors like food preparation methods, type of bread, or portion sizes [9].

- Methodology: Trained interviewers often use a multi-pass approach, such as the USDA's Automated Multiple-Pass Method, to help respondents remember and report their intake. This involves several steps: a quick list of foods consumed, a detailed review of each food (including time, amount, and context), and a final probe for any forgotten items [9] [10]. Visual aids like food models or photographs are frequently employed to improve portion size estimation [9]. A single recall usually takes 20 to 60 minutes to complete [9].

- Data Utility and Limitations: Data from 24HRs can be used to assess population-level intakes, examine diet-health relationships, and evaluate dietary interventions [9]. A key limitation is its reliance on memory, which can lead to omissions and under-reporting, particularly for snack foods, condiments, and alcohol [11] [12]. Because diet varies daily, multiple non-consecutive recalls (often 2-3) are required to estimate an individual's "usual" intake, and statistical methods like the NCI method are used to correct for day-to-day variation [9] [13].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of the 24-Hour Dietary Recall

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Primary Function | Detailed assessment of short-term food & beverage intake [9] |

| Administration | Interviewer-administered or automated self-administered [9] |

| Memory Relied On | Specific memory of the previous 24 hours [9] |

| Key Strength | Provides detailed food-level and context data without reactivity (if unannounced) [9] |

| Primary Measurement Error | Random error, plus systematic under-reporting [9] [12] |

| Optimal Design | Multiple (2+), non-consecutive days, including a weekend day [13] |

The Evolution: Integration of Wearable Cameras

Technological advancements have introduced wearable cameras as a tool to complement and enhance traditional self-report methods. These devices aim to reduce memory-related bias by providing an objective, passive record of consumption [14].

- Defining the Technology: Wearable cameras are small, automatic cameras (e.g., Narrative Clip, Autographer) worn on clothing. They are programmed to capture images at regular intervals (e.g., every 30 seconds), creating a first-person, point-of-view record of the day's activities, including eating and drinking episodes [11] [14].

- Methodological Workflow: The typical research application is image-assisted recall. Participants wear the camera for a day. The following day, they first complete a standard 24HR from memory. Then, together with a researcher, they review the camera images. The images serve as memory cues to help identify and confirm eating episodes, correct portion sizes, and add forgotten items like snacks or beverages [14]. Participants are typically given the opportunity to review and delete any private images before the researcher sees them [15].

The diagram below illustrates this integrated workflow.

Comparative Analysis: 24HR vs. Wearable Cameras

Direct comparative studies quantify the performance differences between standard 24HR and camera-assisted methods.

- Detection of Omitted Foods: A study by Chan et al. found that both 24HR and a food record app frequently omitted specific food groups compared to camera images. Discretionary snacks were a commonly missed category by both self-report methods. Furthermore, items like water, dairy, sugar-based products, condiments, and alcohol were more frequently omitted in the app-based record than in the 24HR [11].

- Impact on Energy and Nutrient Intake: A study with 20 adults compared a standard 24HR to a 24HR assisted by the Narrative Clip camera. The camera-assisted method led to a statistically significant increase in reported mean energy intake (9304.6 kJ/d to 9677.8 kJ/d), as well as higher reported intakes of carbohydrates, total sugars, and saturated fats. This suggests the method mitigates the under-reporting inherent in traditional recall [14].

Table 2: Experimental Data Comparison: Standard 24HR vs. Camera-Assisted 24HR

| Dietary Component | Standard 24HR | Camera-Assisted 24HR | Change & P-Value | Study Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Energy Intake | 9304.6 ± 2588.5 kJ/d | 9677.8 ± 2708.0 kJ/d | +373.2 kJ (P=0.003) | n=20 adults; Narrative Clip camera [14] |

| Omission: Snacks | Frequently Omitted | N/A | (Reference: Camera images) | n=?; Autographer camera [11] |

| Omission: Water | Less Frequent | N/A | More frequent in app (P<0.001) | n=?; Comparison to camera images [11] |

| Omission: Condiments/Fats | Less Frequent | N/A | More frequent in app (P<0.001) | n=?; Comparison to camera images [11] |

Methodological Protocols and Research Reagents

For researchers seeking to implement these methods, a detailed protocol and list of essential resources are provided below.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Camera-Assisted 24HR

The following methodology is adapted from a feasibility study that compared a standard 24HR to a camera-assisted 24HR [14].

- Device Preparation: Select a suitable wearable camera (e.g., Narrative Clip, Autographer). Ensure devices are fully charged and have sufficient memory.

- Participant Briefing and Consent: Obtain informed consent, explicitly addressing image privacy and data handling. Train participants on device operation, proper clipping on clothing, and when it is appropriate to remove the camera (e.g., during sleep, bathing, or in sensitive situations).

- Data Collection Day: Participants wear the camera from waking until going to bed, following their usual activities.

- Standard 24HR Interview (Pre-Image Review): The day after, conduct a standard 24HR interview using a multi-pass method before any images are viewed. This establishes a baseline self-reported intake.

- Private Image Review: Upload images to a secure computer. The participant reviews all images privately and deletes any they are uncomfortable sharing.

- Image-Assisted Recall: The researcher and participant review the remaining images together. The researcher uses the images to prompt the participant:

- "I see an image of a coffee cup at 10:30 AM. Can you tell me more about that?"

- "This image shows your lunch plate. Does that portion size match what you recalled earlier?"

- "There is an image of a snack wrapper at 3:00 PM that wasn't mentioned. What was that item?"

- Data Modification: Record any additions, deletions, or modifications to the initial 24HR based on the image review, creating a final, enhanced dietary record.

- Data Security: Delete all images from the research computer in the presence of the participant after data extraction.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Dietary Assessment Studies

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Wearable Camera (e.g., Narrative Clip, Autographer) | Automatically captures first-person, time-stamped image data of daily activities and food consumption [14]. |

| Structured Interview Protocol (e.g., USDA AMPM) | Standardizes the 24HR interview process to reduce interviewer bias and improve completeness [9] [10]. |

| Portion Size Aids (Food models, atlases, photographs) | Assists participants in estimating and reporting the volume or weight of consumed foods [9] [14]. |

| Dietary Analysis Software (e.g., NDSR, Nutritics, SER-24H) | Converts reported foods and portion sizes into estimated nutrient intakes using a linked food composition database [16] [14]. |

| Food Composition Database | Provides the nutrient profile for each food item; requires localization for cultural relevance (e.g., SER-24H for Chile) [16]. |

Implementation and Feasibility in Research

Choosing between these methods requires balancing accuracy, burden, and cost.

- Feasibility and Challenges of Wearable Cameras:

- Participant Perspective: Studies report high acceptance, with many participants finding image-assisted recall helpful and the experience positive [15] [14]. However, some find the device cumbersome, express emotional discomfort, or may alter their behavior (reactivity) due to being recorded [15].

- Researcher Perspective: Key challenges include data loss from device malfunction (up to 15-50% in some settings) and a high proportion of uncodable images (up to 35%) due to poor lighting, blur, or obstruction [15]. The most significant burden is the labor-intensive, time-consuming process of manually processing and coding thousands of images [11] [15].

- Optimizing Traditional 24HR Surveys: For large-scale studies using 24HR alone, research indicates that administering two non-consecutive days (including one weekday and one weekend day) and adjusting the data using the NCI method is a feasible approach that balances survey costs with accuracy for estimating usual intake of many dietary components [13].

In conclusion, while the 24-hour dietary recall remains a fundamental tool for dietary assessment, its accuracy is compromised by self-report bias. Wearable camera technology presents a promising evolution, objectively demonstrating an ability to reduce under-reporting. The choice for researchers and drug development professionals is not necessarily a binary one; an integrated approach using wearable cameras to validate and enhance traditional 24HR data may offer the most robust path forward for precise dietary measurement in critical research.

Accurate dietary assessment is fundamental to nutritional science, chronic disease management, and public health research. For decades, the 24-hour dietary recall (24HR) has been a cornerstone methodology, relying on an individual's ability to retrospectively recall and self-report all foods and beverages consumed over the previous day [17]. However, this and other self-report methods are plagued by well-documented limitations, including significant recall bias, difficulties in estimating portion sizes, and social desirability bias, which often lead to systematic under-reporting—a problem identified in up to 70% of adults in some national surveys [17]. The landscape of dietary assessment is now undergoing a transformative shift with the emergence of wearable sensor technology, which enables passive, objective, and continuous monitoring of eating behaviors [17] [18]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison between these evolving methodologies, focusing on technological capabilities, performance data, and experimental protocols to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Wearable sensors for dietary monitoring encompass a diverse array of technologies, each capturing different aspects of eating behavior through various physiological and contextual signals.

Sensor Types and Operating Principles

- Motion Sensors (Inertial Measurement Units - IMUs): Typically comprising accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers, these sensors detect patterns of body movement associated with eating, most notably hand-to-mouth gestures [19] [18]. The repetitive motion of bringing food to the mouth creates a characteristic signature that machine learning algorithms can distinguish from other activities.

- Acoustic Sensors: These sensors, often embedded in hearables or neck-worn devices, capture audio signals generated during chewing and swallowing [20]. The sounds of mastication and deglutition provide high-fidelity data on eating microstructure, including bite count and chewing rate.

- Wearable Cameras: Small, body-worn cameras (e.g., eyeglass-mounted or chest-pinned) capture first-person perspective images at regular intervals (e.g., every 30 seconds) [17] [21]. These images provide objective visual records of food consumption, requiring subsequent analysis—either by trained dietitians or increasingly through computer vision and deep learning algorithms—to identify food types and estimate portion sizes [2].

- Optical Sensors (Photoplethysmography - PPG): Commonly integrated into wrist-worn devices like smartwatches, PPG sensors use light-based technology to measure blood volume changes. While primarily used for cardiovascular monitoring, advanced analysis of PPG signals shows promise for detecting eating episodes through hemodynamic changes associated with food intake [22].

Table 1: Wearable Sensor Technologies for Dietary Monitoring

| Sensor Type | Common Form Factors | Primary Measured Parameters | Data Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motion Sensors | Wristbands, Smartwatches | Hand-to-mouth gestures, arm movement patterns | Eating episodes, bite count, meal duration |

| Acoustic Sensors | Necklaces, Hearables | Chewing sounds, swallowing sounds | Eating episodes, chewing rate, food texture indicators |

| Wearable Cameras | Eyeglass attachments, Chest pins | First-person view images of food and eating environment | Food type, eating context, portion size (via image analysis) |

| Optical Sensors (PPG) | Smartwatches, Wristbands | Blood volume changes, heart rate variability | Eating episodes, metabolic responses |

Multi-Sensor Systems

Recognizing that no single sensor modality can comprehensively capture the complexity of dietary intake, researchers are increasingly developing multi-sensor systems that combine complementary technologies [18]. For example, the Automatic Ingestion Monitor (AIM-2) integrates a camera, accelerometer, and gyroscope to capture both visual context and motion data [20]. Similarly, the eButton combines a camera with other sensors in a chest-pinned form factor to improve the accuracy of food identification and portion size estimation [2]. These integrated systems leverage sensor fusion algorithms to correlate multiple data streams, potentially overcoming the limitations of individual sensing approaches.

Comparative Analysis: Wearable Sensors vs. 24-Hour Dietary Recall

The transition from traditional 24HR to sensor-based methods represents a fundamental shift in dietary assessment methodology, with significant implications for data quality, participant burden, and research outcomes.

Performance Comparison

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Dietary Assessment Methods

| Performance Metric | 24-Hour Dietary Recall (24HR) | Wearable Camera Systems | Multi-Sensor Wearable Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Intake Accuracy | Underestimates by 20% or more compared to DLW [17] | MAPE: 28.0-31.9% for portion size [2] | Varies by system; generally superior to self-report |

| Data Collection Timescale | Single day snapshot | Continuous days/weeks [17] | Continuous long-term monitoring [18] |

| Eating Episodes Captured | Frequent omission of snacks, beverages [21] | Identifies 41% more items vs self-report [17] | 65-85% detection accuracy for eating events [18] |

| Portion Size Estimation | High error rate; difficult for complex meals | MAPE: 28.0% (EgoDiet) [2] | Dependent on integrated sensor types |

| Participant Burden | High (active recall/recording) | Medium (passive with privacy concerns) [23] | Low (fully passive after setup) |

| Data Processing Time | Hours per participant (manual coding) | Months for large image datasets [17] | Near real-time with automated algorithms |

Methodological Strengths and Limitations

24-Hour Dietary Recall

- Strengths: Established methodology with standardized protocols (e.g., Automated Self-Administered 24-h recall), comprehensive nutrient databases, and extensive validation research [17] [24].

- Limitations: Systematic under-reporting of energy intake (particularly for snacks and discretionary foods), recall bias dependent on memory, reactivity where participants may alter intake when they know they will be recalled, and inability to capture eating architecture (meal timing, eating rate, within-person variation) [17] [21].

Wearable Sensors

- Strengths: Passive data collection reduces participant burden and reactivity, objective measurement minimizes social desirability bias, enables capture of temporal patterns and eating behaviors, and supports long-term monitoring for habitual intake assessment [17] [18].

- Limitations: Privacy concerns with continuous monitoring, technical challenges with battery life and data management, social acceptability of conspicuous devices, algorithm development requirements for automated analysis, and validation gaps for diverse populations and food types [23] [18].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Rigorous validation is essential for establishing the credibility of wearable sensor technologies for dietary assessment. The following protocols represent current approaches in the field.

Wearable Camera Validation Protocol

The EgoDiet system validation, as described in studies with Ghanaian and Kenyan populations, exemplifies a comprehensive approach to evaluating wearable camera technology [2]:

- Participant Recruitment: Recruit 13 healthy subjects of Ghanaian or Kenyan origin, aged ≥18 years.

- Device Fitting: Participants wear two customized wearable cameras:

- Automatic Ingestion Monitor (AIM): A gaze-aligned wide angle lens camera attached to the temple of eyeglasses (eye-level).

- eButton: A chest-pin-like camera worn using a needle-clip (chest-level).

- Data Collection: Participants consume foods of Ghanaian and Kenyan origin in a controlled facility while cameras record.

- Ground Truth Establishment: Use a standardized weighing scale (e.g., Salter Brecknell) to pre-measure all food items before consumption.

- Image Analysis Pipeline:

- EgoDiet:SegNet: Utilizes Mask R-CNN backbone for segmentation of food items and containers.

- EgoDiet:3DNet: Depth estimation network estimating camera-to-container distance and reconstructing 3D container models.

- EgoDiet:Feature: Extracts portion size-related features including Food Region Ratio (FRR) and Plate Aspect Ratio (PAR).

- EgoDiet:PortionNet: Estimates portion size in weight using extracted features.

- Performance Metrics: Calculate Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) for portion size estimation compared to dietitian assessments and 24HR.

This protocol yielded a MAPE of 31.9% for portion size estimation compared to 40.1% for dietitian estimates, demonstrating the potential for passive camera technology to outperform even expert assessment [2].

Multi-Sensor Eating Detection Protocol

A standardized protocol for validating multi-sensor wearable systems typically includes [23] [18]:

- Laboratory Calibration Phase:

- Participants perform prescribed activities including eating, drinking, and non-eating activities (talking, walking, gesturing).

- Sensor data is collected and annotated to build activity-specific classification models.

- Free-Living Validation Phase:

- Participants wear sensors during normal daily activities for 1-7 days.

- Participants concurrently complete detailed food diaries or ecological momentary assessments (EMA) as ground truth.

- For wearable cameras, trained coders analyze images to identify eating episodes and food items.

- Algorithm Development:

- Feature extraction from sensor data (time-domain, frequency-domain, and sensor-specific features).

- Training of machine learning classifiers (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machines, Deep Neural Networks) to detect eating episodes.

- Performance Evaluation:

- Standard metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score for eating episode detection.

- Timing accuracy: Measurement of detection latency from meal start.

- Comparison against self-report methods for completeness.

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the typical experimental workflow for validating wearable sensors against traditional 24HR:

Experimental Workflow for Dietary Assessment Methods Comparison

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Technologies and Reagents

Implementing wearable sensor technology for dietary monitoring requires familiarity with both hardware platforms and analytical software tools.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Wearable Dietary Monitoring

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wearable Platforms | Automatic Ingestion Monitor (AIM-2), eButton, SenseCam | Multi-sensor data acquisition platform | Battery life, storage capacity, form factor, sensor synchronization |

| Algorithm Development | TensorFlow, PyTorch, scikit-learn | Machine learning model development for activity recognition | Pre-trained models for transfer learning, computational requirements |

| Sensor Fusion Libraries | MATLAB Sensor Fusion & Tracking Toolbox, OpenSense | Integration of multiple sensor data streams | Time synchronization, coordinate transformation, filter design |

| Food Image Databases | Food-101, UNIMIB2016, self-collected datasets | Training and validation of computer vision algorithms | Cultural food representation, portion size annotation, image quality |

| Ground Truth Tools | Standardized weighing scales, Tri-axial accelerometers, Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) | Validation against objective measures | Cost, participant burden, analytical requirements |

| Data Annotation Platforms | Labelbox, CVAT, custom annotation tools | Manual labeling of sensor data for supervised learning | Inter-rater reliability, annotation guidelines, quality control |

Wearable sensor technology represents a paradigm shift in dietary assessment, addressing fundamental limitations of traditional 24-hour dietary recalls by providing objective, passive, and continuous monitoring capabilities. While 24HR retains advantages in established infrastructure and nutrient database integration, wearable sensors offer superior capture of eating timing, frequency, and contextual factors—critical dimensions for understanding diet-health relationships [17] [18].

The field continues to evolve rapidly, with future advancements likely to focus on miniaturization and social acceptance of devices, improved battery life and energy harvesting, development of more robust algorithms for diverse populations and food types, and enhanced privacy preservation techniques [23] [25]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice between methodologies involves careful consideration of trade-offs between precision, participant burden, and practical implementation constraints. As validation evidence accumulates and technology matures, wearable sensors are poised to become increasingly integral to nutritional epidemiology, clinical nutrition, and public health research.

For decades, nutritional epidemiology and clinical drug development have relied heavily on self-reported dietary assessment methods, particularly the 24-hour dietary recall (24HR). This method requires participants to recall and report all foods and beverages consumed over the previous 24 hours to trained dietitians. While widely used, traditional 24HR suffers from several well-documented limitations: it is labor-intensive, expensive, prone to significant reporting bias due to dependence on memory and social desirability, and can lead to systematic under-reporting of energy intake, particularly for between-meal snacks [1] [26]. Furthermore, it only provides a sparse snapshot of eating habits, missing crucial details about eating architecture, such as meal timing, eating speed, and within-person variation [26].

Wearable sensor technologies offer a paradigm shift, enabling passive, objective, and high-resolution data collection in free-living conditions. This guide objectively compares three key wearable sensor modalities—Inertial, Acoustic, and Visual—against traditional 24HR and each other, providing researchers with the experimental data and protocols needed for informed adoption.

Comparative Performance of Wearable Modalities vs. 24HR

The table below summarizes the quantitative performance, primary functions, and key advantages of each wearable modality in direct comparison to the 24HR method.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Wearable Sensor Modalities vs. 24-Hour Dietary Recall

| Modality | Primary Measured Parameters | Key Advantages vs. 24HR | Reported Performance Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual (Wearable Cameras) | Food type, portion size, eating environment, meal timing [27] [26] | Passive capture; minimizes recall bias; provides contextual data (eating environment) [1] | Portion size MAPE: 28.0% (EgoDiet) vs. 32.5% for 24HR [1] |

| Acoustic | Chewing, biting, swallowing counts and rates [27] | Captures micro-level eating behaviors; non-invasive; good for detecting eating episodes [27] | High accuracy for detection of specific actions (e.g., chewing, swallowing) in controlled settings [27] |

| Inertial (IMUs) | Hand-to-mouth gestures, arm and trunk movement, gait [28] [27] [29] | Provides data on physical activity & functional outcomes; useful for gait analysis [28] [30] | Accurately tracks functional metrics like Foot Progression Angle (Accuracy: 2.4° RMS) [29] |

| 24HR (Traditional) | Self-reported food types and estimated portions [1] [26] | Established methodology; no required hardware | Prone to under-reporting; up to 70% of adults under-report energy intake [26] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Wearable Modalities

Visual Sensor Protocol: The EgoDiet Pipeline

The EgoDiet methodology employs a passive, egocentric vision-based pipeline for dietary assessment, validated in field studies in London and Ghana [1].

- 1. Hardware and Data Collection: Participants wear a low-cost, chest-mounted wearable camera (e.g., a "spy badge" form factor) that automatically captures images at set intervals (e.g., every 10-30 seconds) throughout the day [1] [26].

- 2. Image Pre-processing and Food Detection: A convolutional neural network (CNN), such as Mask R-CNN in the

EgoDiet:SegNetmodule, automatically scans all captured images to identify and segment those containing food items and containers [1]. - 3. Portion Size Estimation:

- The

EgoDiet:3DNetmodule, a depth estimation network, reconstructs the 3D model of the container and estimates camera-to-container distance. - The

EgoDiet:Featuremodule extracts portion size-related features like the Food Region Ratio (FRR) and Plate Aspect Ratio (PAR). - Finally, the

EgoDiet:PortionNetmodule uses these features to estimate the portion size in weight, overcoming the challenge of limited training data via task-relevant feature extraction [1].

- The

- 4. Validation: Estimated portion sizes and nutrient intakes are validated against dietitian assessments or objective measures like doubly labeled water [1].

Acoustic Sensor Protocol

This modality uses sensors to capture sounds generated during eating to detect and characterize eating behavior.

- 1. Hardware and Data Collection: A contact microphone or an acoustic sensor embedded in a wearable device (e.g., a neckband) is placed on the skin of the neck or throat. The sensor records audio signals throughout the day or during designated meal periods [27].

- 2. Signal Pre-processing: The raw audio signal is filtered to remove background noise and enhance frequencies associated with chewing and swallowing sounds [27].

- 3. Event Detection and Classification: Machine learning algorithms (e.g., support vector machines or deep learning models) are trained to identify and classify distinct audio events, such as chews, bites, and swallows [27].

- 4. Metric Calculation: The timing and frequency of these events are aggregated to calculate metrics like total chewing counts, chewing rate, eating episode duration, and eating speed [27].

- 5. Validation: Detected eating episodes and metrics are typically validated in laboratory settings by comparing sensor outputs with video recordings or researcher annotations [27].

Inertial Sensor Protocol for Gait Retraining

While also used for detecting eating gestures, inertial sensors are well-established in biomechanical monitoring. The following protocol validates their use in gait retraining, a related application in health monitoring [29].

- 1. Hardware and Sensor Calibration: Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) are securely strapped to the participant's feet, shanks, thighs, and pelvis. The system is calibrated by having the subject stand in a neutral N-pose and then walk a short distance to define the sensor-to-segment alignment [29].

- 2. Data Collection and Processing: While the participant walks on a treadmill, the IMUs stream data from accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers. Sensor fusion algorithms (e.g., within the Xsens MVN software) process this data to compute the orientation and position of body segments in real-time [29].

- 3. Biomechanical Parameter Calculation: The Foot Progression Angle (FPA) is calculated from the derived foot segment orientation relative to the direction of progression [29].

- 4. Biofeedback Delivery: The calculated FPA is fed to a wearable augmented reality headset (e.g., Microsoft HoloLens), which projects a real-time visual gauge (e.g., a moving dot and a target zone) into the user's field of view [29].

- 5. Validation: The system's accuracy is validated against a gold-standard optical motion capture system (e.g., Vicon) while participants follow different FPA targets [29].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

EgoDiet's Computer Vision Pipeline

The following diagram illustrates the multi-stage AI pipeline used by the EgoDiet system to estimate food portion size from passive image capture.

Integrated Multi-Sensor Eating Behavior Assessment

This workflow depicts how data from inertial and acoustic sensors can be fused to provide a comprehensive, objective assessment of eating behavior, contrasting with the subjective 24HR.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for Wearable Dietary and Behavioral Research

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Cost Wearable Camera | Passive, automatic image capture from an egocentric (first-person) view. | Core component of the EgoDiet protocol for capturing eating episodes without user intervention [1] [26]. |

| Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) | Measures linear acceleration (accelerometer), angular velocity (gyroscope), and orientation (magnetometer). | Tracking hand-to-mouth gestures for bite counting or assessing gait parameters for functional outcome measures [27] [29]. |

| Contact Microphone | Captures high-fidelity audio/vibrations from the skin surface. | Detecting and classifying chewing and swallowing sounds for micro-behavioral analysis of eating [27]. |

| Augmented Reality (AR) Headset | Projects visual feedback and data into the user's field of view. | Providing real-time biofeedback for gait retraining or potentially for dietary intervention studies [29]. |

| Fitbit/ActiGraph Activity Tracker | Commercial or research-grade wearable for tracking general physical activity and heart rate. | Collecting complementary data on energy expenditure and daily activity patterns in free-living studies [31]. |

| Fitabase Platform | A secure third-party data aggregation and management tool. | Remotely collecting, monitoring, and managing data quality from multiple commercial wearables (e.g., Fitbit) in a study [31]. |

| Xsens MVN Analyze Software | Software for processing raw IMU data into full-body kinematic data. | Calculating biomechanical parameters like Foot Progression Angle (FPA) for movement retraining studies [29]. |

The field of dietary assessment is undergoing a significant transformation. Since 2020, research has increasingly focused on overcoming the limitations of traditional self-report methods by developing and validating more objective, technology-driven tools. This guide provides an objective comparison between an emerging method—wearable cameras—and the established standard of 24-hour dietary recalls, detailing their respective experimental protocols, performance data, and essential research toolkits.

Experimental Performance Data Comparison

The table below summarizes quantitative data from recent validation studies, comparing the performance of wearable camera-assisted methods against traditional and web-based 24-hour dietary recalls.

| Methodology | Study & Population | Key Performance Metrics | Identified Limitations / Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wearable Camera-Assisted Recall | Northern Ireland (n=20 adults) [14] | Energy Intake: Significantly higher in camera-assisted recall vs. recall alone (9677.8 ± 2708.0 kJ/d vs. 9304.6 ± 2588.5 kJ/d; P = 0.003) [14]. | Technological issues (positioning), data loss (15%), uncodable images (12%) due to lighting, labor-intensive analysis [14] [15]. |

| Wearable Camera (EgoDiet AI) | Ghana & London (Ghanaian/Kenyan origin) [2] | Portion Size MAPE: 28.0% (EgoDiet) vs. 32.5% (24HR) [2]. Performance varies with camera position (chest vs. eye-level) [2]. | Requires algorithm optimization for different cuisines; performance dependent on camera positioning and lighting [2]. |

| Web-Based 24HR (Foodbook24) | Irish, Polish, Brazilian adults in Ireland [6] | Food List Coverage: 86.5% (302/349 foods consumed were available in the tool) [6]. Correlation: Strong (r=0.70-0.99) for 44% of food groups and 58% of nutrients vs. interviewer-led recall [6]. | Higher food omission rates in certain groups (e.g., 24% in Brazilian cohort vs. 13% in Irish) [6]. |

| Web-Based 24HR (Intake24) | South Asian Biobank (n=29,113) [32] | Recall Completion Time: Median of 13 minutes [32]. Data Quality: 99% of recalls contained >8 items; 8% had missing foods [32]. | Requires development of a large, context-specific food database (2,283 items for South Asia) [32]. |

| Wearable Camera as Objective Reference | Young Australian Adults (n=133) [21] | Omission Analysis: Discretionary snacks frequently omitted in both 24HR and app-based records. Water, dairy, condiments, fats, and alcohol more frequently omitted in app-based records [21]. | Method is intrusive; privacy concerns for participants; generates massive datasets (487,912 images for 133 participants) [21]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Wearable Camera-Assisted 24-Hour Recall Protocol

This protocol, used to validate the method against traditional recalls, involves a hybrid approach that uses wearable camera images as memory prompts [14].

a. Equipment and Pre-Data Collection:

- Camera Selection: Studies often use small, automatic cameras like the Narrative Clip (a 5-megapixel device clipped onto clothing), chosen for its discreteness, automatic image capture (e.g., every 30 seconds), and sufficient battery life [14].

- Participant Briefing: Participants receive training on device operation, including charging and correct placement on clothing. Critical ethical instructions are provided: participants can remove the camera in private situations (e.g., bathrooms) or if they feel uncomfortable [14] [21].

b. Data Collection:

- Camera Wear: Participants wear the camera during waking hours for one or more designated study days [14].

- 24-Hour Recall Interview: Conducted the day after camera wear. The researcher conducts a standard multi-pass 24-hour recall without viewing the images first [14].

c. Image-Assisted Recall and Data Processing:

- Image Review: Camera images are uploaded. Participants first privately review and delete any images they do not wish to share to protect privacy [14] [15].

- Recall Augmentation: The researcher and participant review the images together. The images serve as memory cues to confirm, add, remove, or modify details of food items, portion sizes, and eating context reported in the initial recall [14]. All changes are documented for analysis.

Web-Based 24-Hour Dietary Recall (Foodbook24/Intake24) Protocol

This protocol outlines the adaptation and implementation of automated, self-administered 24-hour recall tools for diverse populations [6] [32].

a. Tool Adaptation and Database Development:

- Food List Expansion: The core food list is expanded by reviewing national food consumption surveys and relevant literature for the target populations (e.g., Brazilian, Polish, South Asian foods) [6] [32].

- Translation and Nutrient Mapping: Food items are translated into relevant languages (e.g., Polish, Portuguese). Nutrient composition data are assigned, primarily from national food composition databases (e.g., UK's CoFID), with local databases used for culturally specific items [6] [32].

- Portion Size Estimation: Medium portion sizes are typically derived from the mean reported intake in national surveys. Small and large portions are defined using standard deviations or established portion size manuals. Food images are used to aid user estimation [6].

b. Data Collection:

- Recall Administration: Participants complete the recall independently using a computer or smartphone. The system guides them through a structured process (similar to the multiple-pass method) to report all foods and beverages consumed in the previous 24 hours, including food selection and portion size estimation [6] [32].

- Interviewer-Led Option: In some populations, trained interviewers may administer the web-based tool to participants to ensure compliance and data quality [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key materials and tools essential for conducting research in this field.

| Tool / Solution | Function in Dietary Assessment Research |

|---|---|

| Wearable Cameras (Narrative Clip, Autographer, eButton) | Capture passive, objective, first-person-view images of eating episodes and daily activities, used for memory triggering or as a validation reference [14] [21] [2]. |

| AI-Based Analysis Pipelines (EgoDiet) | Software suite for automated dietary assessment from wearable camera images, performing food segmentation, 3D container reconstruction, and portion size estimation [2]. |

| Web-Based 24HR Platforms (Foodbook24, Intake24) | Automated, structured systems for conducting self-administered 24-hour dietary recalls, featuring built-in food lists, portion size images, and immediate nutrient analysis [6] [32]. |

| Food Composition Database (FCDB) | The nutrient lookup table for converting reported food consumption into nutrient intake data. Requires careful integration of data from multiple national databases for multi-ethnic studies [6] [32]. |

| Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) | Objective biomarker used as a gold standard for validating total energy expenditure and, by extension, the accuracy of reported energy intake in validation studies [26]. |

Method Workflow Comparison

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental operational differences between the passive, image-capture-focused workflow of wearable cameras and the active, participant-driven workflow of web-based 24-hour recalls.

Research since 2020 demonstrates that both wearable cameras and web-based 24-hour recalls are evolving to address critical challenges in dietary assessment. Wearable cameras offer a more objective ground truth and are particularly valuable for identifying under-reporting and validating other methods. Web-based recalls provide a scalable, cost-effective solution for large-scale studies, especially when adapted for cultural and linguistic diversity. The choice between methods depends on the research question, budget, and population. Future work is focused on integrating these approaches, for instance, using AI analysis of wearable camera data to further automate and improve the accuracy of dietary intake estimation.

Operational Mechanisms and Application-Specific Implementation

The accurate measurement of dietary intake is a cornerstone of nutritional epidemiology, public health monitoring, and clinical trials. For decades, the 24-hour dietary recall (24HR) has served as a fundamental tool for capturing individual food and beverage consumption. However, traditional recall methods are susceptible to significant limitations, including recall bias, participant burden, and measurement error [21]. The digital era has introduced transformative technologies aimed at mitigating these challenges. This guide provides an objective comparison of two modern approaches to executing the 24HR: established web-based platforms and emerging image-assisted methods, often supported by wearable technology. This comparison is situated within the broader thesis of understanding the trade-offs between automated self-report tools and more passive, objective measurement systems in dietary research. As the field advances, researchers must navigate a complex landscape of tools that balance accuracy, feasibility, and participant engagement.

Methodological Comparison: Protocols and Experimental Designs

Web-Based Automated 24HR Platforms

Web-based 24HR systems are digital adaptations of the interviewer-led multiple-pass method. These platforms, such as the Automated Self-Administered 24-hour Dietary Assessment Tool (ASA-24), guide users through a structured process to report all foods and beverages consumed in the preceding 24 hours [33]. The standard protocol involves:

- Structured Recall Process: Users are guided through a multi-step sequence to report meal contexts, specific food items, ingredients, preparation methods, and portion sizes using digital image aids [33].

- Self-Administration: The tool is designed for independent use by participants without interviewer assistance, typically requiring 30-50 minutes to complete [33].

- Integrated Food Databases: These systems utilize extensive food composition databases with nutrient profiles and portion size images to standardize data collection [33].

A recent pilot study (2023-2024) evaluated a novel voice-based dietary recall tool (DataBoard) against the traditional ASA-24 in older adults (mean age 70.5 ± 4.26 years). Participants were randomly assigned to complete either tool first via Zoom sessions, followed by semi-structured interviews to assess usability and acceptability on a 1-10 rating scale [33].

Image-Assisted Interview Methods

Image-assisted interviews represent a technological hybrid, combining wearable cameras with subsequent researcher-led interviews. The methodology generally follows this protocol:

- Passive Image Capture: Participants wear an automated camera (e.g., Autographer) that captures first-person perspective images at regular intervals (e.g., every 30 seconds) during waking hours [21].

- Image-Assisted Recall: The following day, researchers use the captured images as memory prompts during a structured interview to help participants recall and detail their dietary intake [15].

- Privacy Protection: Participants are typically given the opportunity to review and delete sensitive images before the researcher views them [15].

This method was evaluated in a 2021 study where young adults (18-30 years) wore cameras for three consecutive days while simultaneously reporting dietary intake via a smartphone app and completing daily 24HRs. Camera images were subsequently reviewed and coded by dietitians to identify omitted food items [21]. A 2023 feasibility study in rural Uganda further tested this approach with mothers of young children, assessing both dietary diversity and time use [15].

Performance Metrics: Quantitative Comparison

The table below summarizes key performance metrics for web-based and image-assisted 24HR methods based on recent study findings.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Modern 24HR Methodologies

| Performance Metric | Web-Based 24HR (ASA-24) | Voice-Based 24HR (DataBoard) | Image-Assisted Recall |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usability/Acceptability Rating | 6.7/10 [33] | 7.6-7.95/10 [33] | 92% "good" or "very good" experience [15] |

| Participant Preference | Baseline | 7.2/10 preference over ASA-24 [33] | N/A |

| Data Loss Issues | Minimal | Minimal | 11-50% due to device malfunction [15] |

| Uncodable Data Proportion | N/A | N/A | 1-35% of images [15] |

| Frequently Omitted Items | Discretionary snacks [21] | Discretionary snacks [21] | Dairy, condiments, fats, alcohol [21] |

| Completion Time | 30-50 minutes [33] | Shorter than ASA-24 [33] | Varies by number of images |

Table 2: Objectively Measured Food Omissions by Assessment Method

| Food Category | Omission Rate in Web-Based App | Omission Rate in Traditional 24HR |

|---|---|---|

| Discretionary Snacks | Significant (p<0.001) [21] | Significant (p<0.001) [21] |

| Water | Significant (p<0.001) [21] | Less than app (p<0.001) [21] |

| Dairy & Alternatives | 53% more omissions [21] | Baseline |

| Savoury Sauces & Condiments | Significant (p<0.001) [21] | Baseline |

| Fats & Oils | Significant (p<0.001) [21] | Baseline |

| Alcohol | Significant (p=0.002) [21] | Baseline |

Analysis of Methodological Strengths and Limitations

Web-Based and Voice-Enabled Platforms

Strengths:

- Standardization: Automated administration ensures consistent questioning across all participants, eliminating interviewer bias [33].

- Scalability: Can be deployed to large populations simultaneously with minimal additional resource requirements [33].

- Participant Acceptance: Voice-based systems in particular show promise for older adults and those with technological barriers, with studies reporting higher preference ratings (7.2/10) over traditional web-based systems [33].

Limitations:

- Persistent Omission Issues: Even technology-enhanced self-report methods continue to struggle with accurate capture of commonly forgotten items like discretionary snacks, condiments, and beverages [21].

- Recall Dependence: Remains vulnerable to memory limitations and estimation errors, particularly for mixed dishes and portion sizes [21].

- Digital Literacy Requirements: May present barriers for certain demographic groups, though voice interfaces show potential to mitigate this [33].

Image-Assisted and Wearable Camera Methods

Strengths:

- Objectivity: Provides an objective record of intake that is not solely dependent on participant memory, serving as a valuable validation tool [21].

- Enhanced Recall: Images significantly improve participants' ability to recall and detail consumed items, with most participants reporting the image-review process as helpful [15].

- Contextual Data: Captures rich contextual information about eating environments, social settings, and food sources that are difficult to obtain through recall alone [15].

Limitations:

- Technical Challenges: Significant data loss (11-50%) occurs due to device malfunction, battery failure, or operator error [15].

- Resource Intensity: Requires substantial researcher time for image processing, coding, and analysis, creating scalability constraints [15].

- Privacy Concerns: Participants may experience discomfort wearing cameras in certain settings, potentially leading to behavior modification or study withdrawal [15].

- Image Quality Issues: 1-35% of images may be uncodable due to poor lighting, obstructed views, or camera positioning [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Materials for Implementing Modern Dietary Assessment Methods

| Tool/Solution | Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Dietary Recalls | Self-administered 24-hour recall collection | ASA-24, Intake-24, MyFood24 [21] |

| Voice Survey Platforms | Speech-based dietary data collection | DataBoard (SurveyLex) [33] |

| Wearable Cameras | Passive image capture for dietary behavior | Autographer [21] |

| Image Coding Software | Systematic analysis of captured dietary images | Dedoose [33], Microsoft Excel [21] |

| Egocentric Vision Algorithms | AI-based food identification and portion estimation | EgoDiet (SegNet, 3DNet, Feature, PortionNet) [1] |

| Data Management Systems | Secure storage and management of dietary data | REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) [21] |

The choice between web-based platforms and image-assisted methods for implementing the modern 24HR depends heavily on research objectives, resource constraints, and participant characteristics. Web-based systems offer a practical balance of standardization, scalability, and participant burden for large-scale studies where precise nutrient estimation is the primary goal. The emergence of voice-based interfaces shows particular promise for enhancing accessibility in older populations and those with technological limitations.

Image-assisted methods provide superior objectivity and contextual data, making them invaluable for validation studies, intensive behavioral research, and investigations where the eating environment is a key variable. However, their technical complexity, privacy implications, and resource demands currently limit their application to smaller, more focused studies.

Future directions point toward hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of both methodologies. The integration of AI-assisted image analysis, as seen in systems like EgoDiet which reduces portion size estimation error to 28.0% MAPE compared to 32.5% for traditional 24HR [1], promises to reduce the analytical burden of image-based methods. As these technologies mature, researchers will be better equipped to overcome the persistent challenges of dietary assessment while generating richer, more accurate nutritional data.

Figure 1: Workflow comparison of modern 24-hour dietary recall methodologies, highlighting the distinct processes for web-based, voice-based, and image-assisted approaches.

Accurate dietary assessment is fundamental to understanding the relationship between nutrition and health, yet traditional methods have long been hampered by significant limitations. The 24-hour dietary recall, a cornerstone of nutritional epidemiology, requires participants to retrospectively report all foods and beverages consumed in the preceding 24 hours, typically through an interviewer-administered format. While this method provides valuable dietary data, it suffers from well-documented recall biases, measurement errors, and social desirability biases that can distort true intake reporting [17]. Recent analyses suggest that self-reported methods may capture a maximum of 80% of true intake, with systematic under-reporting identified in up to 70% of adults in national surveys [17]. These limitations have propelled the development of wearable sensor technology that offers a more objective, continuous, and contextual approach to monitoring eating behavior.

Wearable devices represent a paradigm shift from subjective recall to objective, passive data collection, transforming what's possible for measuring habitual intakes and temporal eating patterns. By automatically detecting eating events through motion, acoustic, or visual sensors, these technologies capture rich datasets about not just when eating occurs, but also the behavioral and contextual factors surrounding food consumption [34]. This comparison guide examines the operational mechanisms of wearable eating detection systems, their performance relative to traditional 24-hour recall methods, and their emerging role in nutrition research and clinical applications.

How Wearables Detect Eating: Sensing Technologies and Mechanisms

Wearable eating detection systems employ multiple sensing modalities to identify eating events through characteristic physiological signals and movement patterns. The table below summarizes the primary technologies and their detection mechanisms.

Table 1: Wearable Sensor Technologies for Eating Detection

| Sensing Modality | Detection Mechanism | Measured Parameters | Common Form Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inertial Sensing [34] [27] | Captures wrist and arm kinematics during hand-to-mouth movements | Acceleration, angular velocity, movement patterns | Smartwatches, wristbands, IMU sensors |

| Acoustic Sensing [27] | Detects sounds produced during chewing and swallowing | Acoustic frequency, amplitude, timing | Neck-mounted sensors, in-ear devices |

| Image-Based Sensing [17] [35] | Visually identifies food intake and food type | Food appearance, volume, composition | Wearable cameras, smartphone cameras |

| Physiological Sensing [36] | Monitors metabolic responses to food intake | Heart rate, skin temperature, oxygen saturation | Chest patches, wristbands |

| Bioimpedance Sensing [36] | Measures electrical impedance changes during swallowing | Impedance variations across neck/chest | Necklaces, chest patches |

Inertial Sensing: Tracking Hand-to-Mouth Movements

Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) containing accelerometers and gyroscopes represent the most widely deployed eating detection technology. These sensors detect the characteristic repetitive forearm rotations and elevations that occur during eating episodes. A typical eating detection pipeline using inertial sensing involves multiple stages, as illustrated below:

Figure 1: Inertial Sensing Eating Detection Workflow

This approach has demonstrated strong performance in field deployments. One smartwatch-based system achieved a precision of 80%, recall of 96%, and F1-score of 87.3% in detecting meal episodes, successfully capturing 96.48% (1259/1305) of meals consumed by participants in a real-world study [37]. The system triggered Ecological Momentary Assessments (EMAs) when it detected 20 eating gestures within a 15-minute window, enabling contextual data collection near real-time.

Multi-Sensor Fusion: The Northwestern University Approach

Advanced eating detection systems combine multiple sensors to improve accuracy and capture complementary aspects of eating behavior. Researchers at Northwestern University developed an integrated system employing three synchronized wearable sensors:

Table 2: Multi-Sensor Eating Detection System (Northwestern University)

| Sensor Device | Function | Technical Innovation | Data Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| NeckSense [38] [39] | Precisely records eating behaviors | Neck-worn inertial and acoustic sensing | Bite count, chewing rate, hand-to-mouth movements |

| HabitSense [38] [39] | Captures food-related visual context | Activity-Oriented Camera with thermal food detection | Food presence, type (via thermal signature) |

| Wrist-worn Actigraphy [38] [39] | Monitors general activity and context | Standard accelerometry paired with specialized algorithms | Activity patterns, sleep/wake cycles |

This multi-sensor approach enabled the identification of five distinct overeating patterns in individuals with obesity: take-out feasting, evening restaurant reveling, evening craving, uncontrolled pleasure eating, and stress-driven evening nibbling [38] [39]. The classification emerged from two weeks of continuous monitoring in 60 participants, generating thousands of hours of multimodal sensor data correlated with self-reported mood and context.

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Protocol for Validating Wearable Eating Detection

Rigorous validation is essential to establish the accuracy of wearable eating detection systems. The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive validation protocol adapted from recent studies:

Figure 2: Wearable Eating Detection Validation Protocol

A recent study protocol published in 2025 outlines a controlled approach to validating multi-sensor wearables [36]. The study recruits 10 healthy volunteers who attend two study visits at a clinical research facility, consuming pre-defined high-calorie (1052 kcal) and low-calorie (301 kcal) meals in randomized order. Participants wear a customized multi-sensor wristband that tracks hand-to-mouth movements (via IMU), heart rate, skin temperature, and oxygen saturation throughout the eating episodes. These sensor readings are validated against bedside monitors and frequent blood sampling for glucose, insulin, and hormone levels [36].

Camera-Based Ground Truth Validation

Wearable cameras have emerged as a valuable ground truth method for validating both wearable sensors and self-report measures. In one methodology, participants wear an Autographer camera that captures point-of-view images every 30 seconds during waking hours [35]. Trained dietitians then code these images for food and beverage consumption, categorizing eating episodes by meal type, food category, and nutritional quality. This approach identified significant omission patterns in both app-based food records and 24-hour recalls, particularly for discretionary snacks, water, and alcohol [35].

Performance Comparison: Wearables vs. 24-Hour Dietary Recall

Direct comparisons between wearable sensors and 24-hour dietary recall reveal complementary strengths and limitations for dietary assessment.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Dietary Assessment Methods

| Parameter | Wearable Sensors | 24-Hour Dietary Recall |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Accuracy | 80-96% for eating episodes [37] | Limited by recall bias and portion size estimation [17] |

| Contextual Data | Captures real-time context (location, activity, company) [37] | Limited contextual detail, reliant on memory |

| Food Identification | Limited without image support (multi-sensor systems improving) [17] | Detailed food identification through interview process |

| Portion Size Estimation | Challenging; requires camera systems [17] [35] | Error-prone, dependent on memory and estimation skills |

| Participant Burden | Low after initial setup (passive monitoring) [34] | Moderate to high (requires detailed reporting) |

| Data Processing | Complex computational pipelines, machine learning [34] [27] | Labor-intensive for researchers (coding, analysis) |

| Omission Patterns | Fewer omissions for snacks and beverages [35] | Significant omissions for snacks, water, condiments [35] |

| Temporal Resolution | Continuous, micro-level patterns [34] | Daily or meal-level summary |

Omission Patterns and Measurement Gaps

Discrepancy analyses between camera-based ground truth and self-report methods reveal systematic omission patterns. One study found that discretionary snacks were frequently omitted in both 24-hour recalls and smartphone apps [35]. Specific food categories showed different omission rates: dairy and alternatives, sugar-based products, savory sauces and condiments, fats and oils, and alcohol were more frequently omitted in app-based reporting compared to 24-hour recalls [35]. Water was omitted more frequently in apps than in both camera images and 24-hour recalls.

Wearable sensors address some but not all these gaps. Inertial sensors effectively detect eating events but provide limited information about food type and quantity without complementary sensing modalities. Camera-based systems offer better food identification but raise privacy concerns and require complex image processing [17].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Eating Behavior Research

The experimental approaches described require specialized tools and methodologies. The following table details key research reagents and their applications in eating behavior studies.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Eating Behavior Studies

| Research Tool | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-Sensor Wearable Platform [38] [36] | Simultaneously captures motion, physiological, and contextual data | Northwestern's 3-sensor system; Custom wristbands with IMU, PPG, temperature sensors |

| Activity-Oriented Camera (AOC) [38] [39] | Privacy-preserving image capture triggered by food presence | HabitSense bodycam with thermal food detection |

| Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) [37] | Captures self-reported context in real-time | Smartphone-prompted surveys on eating context, company, mood |

| Standardized Meal Protocols [36] | Provides controlled energy challenges for validation | High-calorie (1052 kcal) and low-calorie (301 kcal) test meals |

| Biomarker Assays [36] | Objective physiological validation of intake | Blood glucose, insulin, hormone level measurements |

| Annotation Software [35] | Enables manual coding of eating episodes from video | Custom coding schedules for meal type, food category, context |

Wearable sensors and 24-hour dietary recall offer complementary rather than competing approaches to dietary assessment. Wearables excel at objective detection of eating timing, frequency, and behavioral patterns with minimal participant burden, while 24-hour recalls provide detailed nutritional composition data that current sensors cannot fully capture.

The emerging research paradigm integrates both approaches: using wearables for continuous monitoring of eating architecture and context, while employing periodic 24-hour recalls for detailed nutritional assessment. This hybrid methodology leverages the strengths of both techniques while mitigating their respective limitations.

For researchers and drug development professionals, wearable sensors offer unprecedented insights into real-world eating behaviors and patterns that can inform intervention development and clinical trial endpoints. As sensor technology continues advancing, with improvements in multi-sensor fusion, privacy preservation, and automated food identification, these tools are poised to become increasingly valuable components of comprehensive dietary assessment protocols.

Accurate dietary assessment is fundamental to nutritional epidemiology, yet traditional methods are plagued by inherent limitations. The 24-hour dietary recall (24HR), a self-report tool reliant on participant memory, has been a long-standing standard despite its susceptibility to recall bias and measurement error [40] [14]. In recent years, wearable technology has emerged as a promising alternative, offering the potential for more objective, passive data collection [41] [2]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these two approaches, evaluating their performance, detailed experimental protocols, and applicability across diverse research populations, from pediatric to geriatric cohorts. The thesis underpinning this comparison is that while wearable devices can significantly improve the accuracy of dietary data collection, their feasibility and performance are modulated by population-specific characteristics and technological constraints.

The table below summarizes key performance metrics for wearable devices and 24-hour recalls, based on recent validation studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Wearable Devices and 24-Hour Recalls

| Metric | Wearable Cameras (with AI Analysis) | Web-Based 24HR (myfood24) | Traditional 24HR (Camera-Assisted) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Portion Size Estimation Error (MAPE) | 28.0% - 31.9% [2] | Information Missing | 32.5% [2] |

| Energy Intake Reporting | Significantly higher vs. recall alone (p=0.003) [14] | Correlated with total energy expenditure (ρ=0.38) [3] | Prone to under-reporting [14] |

| Correlation with Biomarkers | Not Directly Measured | Serum folate (ρ=0.62), Urinary potassium (ρ=0.42) [3] | Not Directly Measured |

| Reproducibility (Correlation) | Not Directly Measured | Strong for most nutrients (e.g., folate ρ=0.84) [3] | Not Directly Measured |

| Data Loss/Uncodable Media | 12-15% (e.g., due to lighting) [15] | Not Applicable | Not Applicable |

Table 2: Feasibility and Acceptability Across Populations

| Population | Wearable Camera Feasibility | 24HR Feasibility |

|---|---|---|

| General Adults (High-Income) | Feasible; some burden and reactivity reported [15] | Well-established; web-based tools show good validity [3] |

| Rural, Low-Income Settings | Challenging; device malfunction, lighting issues, but overall positive participant experience [15] | Impractical for low-literacy populations without an interviewer [15] |

| Pediatric | Limited specific data; likely high burden and privacy concerns | Prone to significant recall error in younger children [40] |

| Geriatric | Limited specific data; potential challenges with technology adoption | Feasible, but may be affected by cognitive decline |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To understand the data presented above, it is crucial to examine the methodologies of key experiments validating these tools.

Protocol for Validating a Web-Based 24HR Tool

A 2025 repeated cross-sectional study assessed the validity and reproducibility of the myfood24 dietary assessment tool against biomarkers in healthy Danish adults [3].

- Participants: 71 healthy adults (53.2 ± 9.1 years) [3].

- Experimental Design: Participants completed a seven-day weighed food record using myfood24 at baseline and again four weeks later. This design allowed for both validity and reproducibility (reliability) testing [3].

- Objective Measures: At the end of each recording week, objective measures were collected:

- Data Analysis: Spearman's rank correlations were calculated between estimated nutrient intakes from myfood24 and the corresponding biomarker levels (e.g., folate intake vs. serum folate, potassium intake vs. urinary potassium) [3].

Protocol for Wearable Camera-Assisted Recall

A 2022 study examined whether a wearable camera could improve the accuracy of a 24-hour recall in twenty adults [14].

- Participants: 20 healthy, free-living volunteers aged 18–65 years [14].

- Wearable Device: The "Narrative Clip" camera, chosen for its automatic image capture (every 30 seconds), discreet size, and ease of use. Participants wore it for one full day [14].

- Experimental Procedure:

- Camera Deployment: Participants wore the camera from wake-up until bedtime.

- Initial 24HR: The following day, a standard 24-hour recall was conducted before viewing any camera images.

- Image-Assisted Recall: Participants first privately reviewed and deleted any images for privacy. Then, the researcher and participant viewed the images together to identify eating episodes, cross-reference the initial recall, and add, remove, or modify details [14].

- Data Analysis: Energy and nutrient intakes from the recall-alone and the camera-assisted recall were compared using paired statistical tests (e.g., paired t-test) [14].

Protocol for AI-Based Passive Dietary Assessment

A 2024 study developed and tested "EgoDiet," an AI-driven pipeline for dietary assessment using low-cost wearable cameras in African populations [2].

- Study Populations:

- AI Pipeline (EgoDiet): The system comprised several modules:

- EgoDiet:SegNet: A neural network to segment food items and containers in images.

- EgoDiet:3DNet: A network to estimate camera-container distance and reconstruct 3D container models.

- EgoDiet:Feature: An extractor for portion size-related features.

- EgoDiet:PortionNet: A final module to estimate the portion size (weight) of food consumed [2].

- Validation: EgoDiet's portion size estimates were compared against assessments by dietitians and against traditional 24HR, with performance measured by Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) [2].

Visualizing Workflows and Technologies

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows and technological concepts discussed in the experimental protocols.

Diagram 1: AI-Powered Wearable Camera Workflow

Diagram 2: Recall Methods Comparison